A lot of you are packaging code into container images before shipping it off to production. That’s cool. For many, this isn’t a one-time exercise at the end of a project; it’s an ongoing exercise throughout the lifespan of your product. Last week in Barcelona, I did a presentation at VMworld Europe where I took a custom app, ran tests in a pipeline, containerized it, and pushed to a cloud runtime. I did all of this with fresh open-source technologies like Kubernetes, Concourse, and kpack. For this blog post, I’ll show you my setup, and for fun, take the resulting container image and deploy it, unchanged, to one Microsoft Azure service, and one Pivotal service.

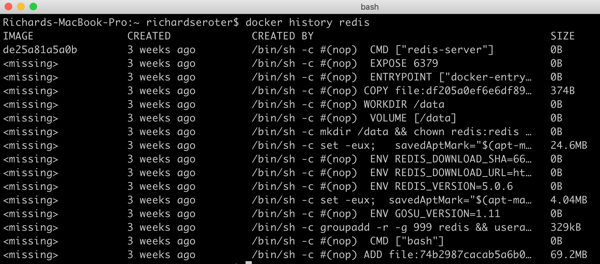

First off, containers. Let’s talk about them. The image that turns into running container is made up of a series of layers. This union of read-only layers gets mounted to present itself as a single filesystem. Many commands in your Dockerfile, generate a layer. When I pull the latest Redis image, and run a docker history command, I see all the layers:

Ok, Richard, we get it. Like onions and ogres, images have layers. I bring it up, because responsibly maintaining a container image means continually monitoring and updating those layers. For a custom app, that means updating layers that store app code, the web server, and the root file system. All the time. Ideally, I want a solution that automatically builds and patches all this stuff so that I don’t have to. Whatever pipeline to production you build should have that factored in!

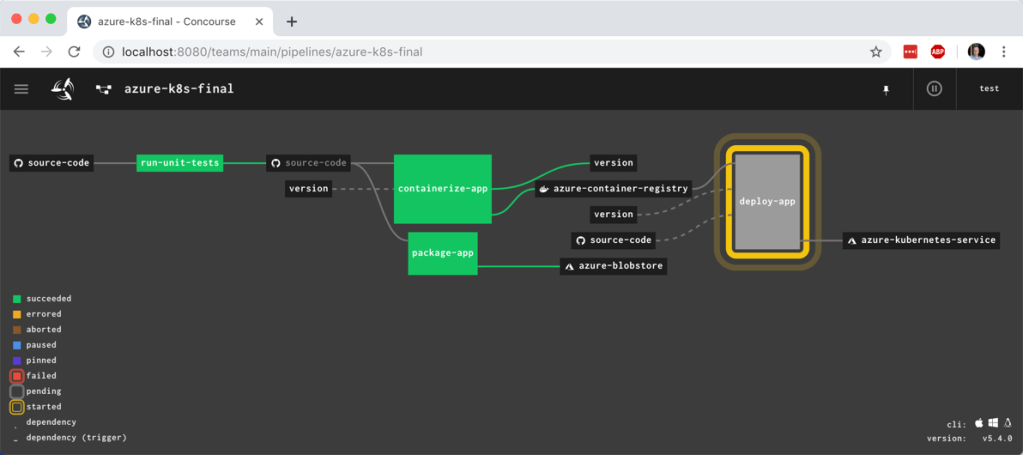

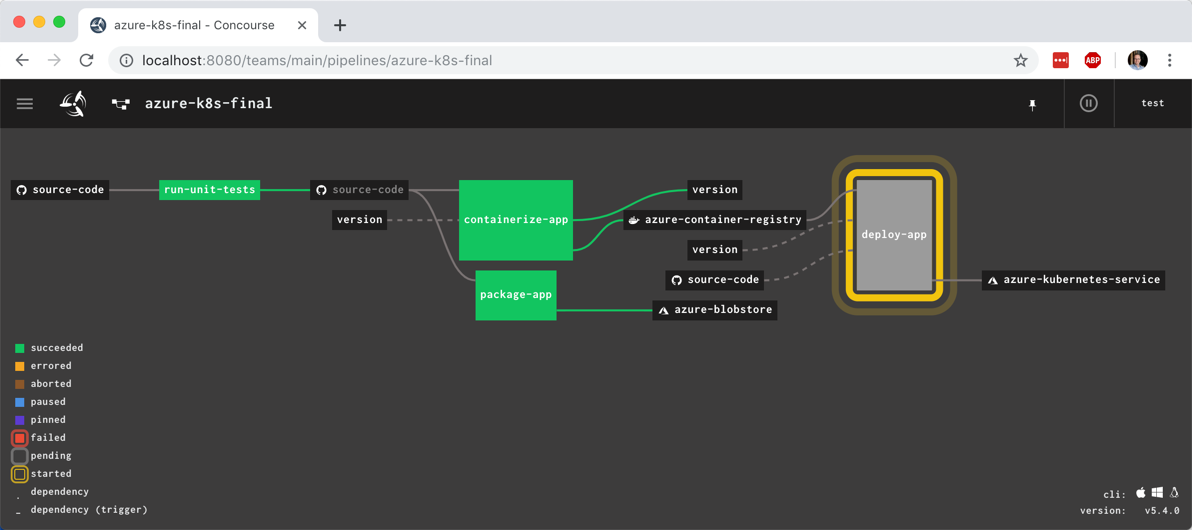

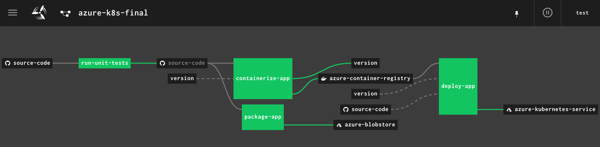

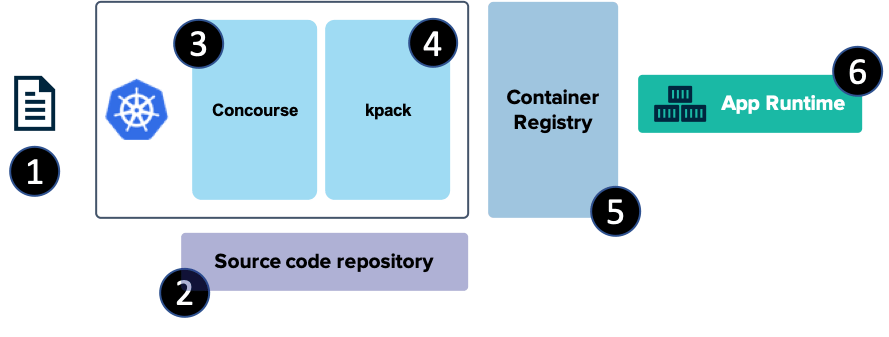

Let’s get to it. Here’s what I built. After coding a Spring Boot app, I checked the code into a GitHub master branch. That triggered a Concourse pipeline (running in Kubernetes) that ran unit tests, and promoted the code to a “stable” branch if the tests passed. The container build service (using the kpack OSS project) monitored the stable branch, and built a container image which got stored in the Docker Hub. From there, I deployed the Docker image to a container-friendly application runtime. Easy!

Step #1 – Build the app

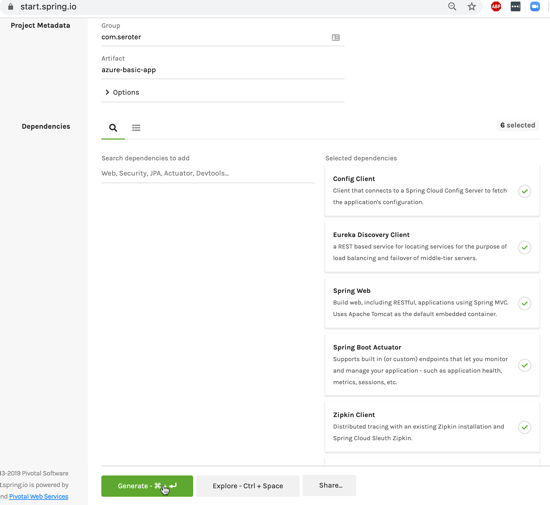

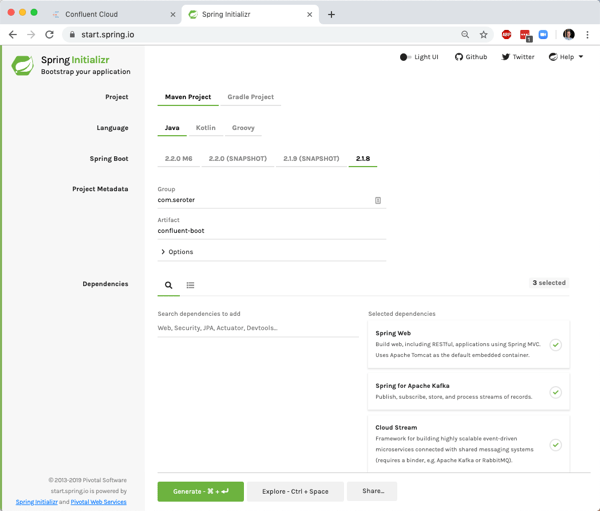

The app is simple, and relatively inconsequential. Build a .NET app, Go app, Node.js app, whatever. I built a Spring Boot app using Spring Initializr. Click here to download the same scaffolding. This app will simply serve up a web endpoint, and also offer a health endpoint.

In my code, I have a single RESTful endpoint that responds to GET requests at the root. It reads an environment variable (so that I can change it per runtime), and returns that in the response.

@RestController

public class GreetingController {

@Value("${appruntime:Spring Boot}")

private String appruntime;

@GetMapping("/")

public String SayHi() {

return "Hello VMworld Europe! Greetings from " + appruntime;

}

}

I also created a single JUnit test to check the response value from my RESTful service. I write great unit tests; don’t be jealous.

@RunWith(SpringRunner.class)

@SpringBootTest(webEnvironment = WebEnvironment.RANDOM_PORT)

public class BootKpackDemoApplicationTests {

@LocalServerPort

private int port;

@Autowired

private TestRestTemplate restTemplate;

@Test

public void testEndpoint() {

assertThat(this.restTemplate.getForObject("http://localhost:" + port + "/",

String.class)).contains("Hello");

}

}

After crafting this masterpiece, I committed it to a GitHub repo. Ideally, this is all a developer ever has to do in their job. Write code, test it, check it in, repeat. I don’t want to figure out the right Dockerfile format, configure infrastructure, or any other stuff. Just let me write code, and trigger a pipeline that gets my code securely to production, over and over again.

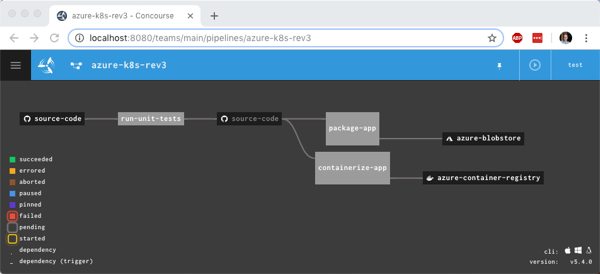

Step #2 – Set up the CI pipeline

For this example, I’m using minikube on my laptop to host the continuous integration software and container build service. I got my Kubernetes 1.15 cluster up (since Concourse currently works up to v 1.15) with this command:

minikube start --memory=4096 --cpus=4 --vm-driver=hyperkit --kubernetes-version v1.15.0

Since I wanted to install Concourse in Kubernetes via Helm, I needed Helm and tiller set up. I used a package manager to install Helm on my laptop. Then I ran three commands to generate a service account, bind a cluster role to that service account, and initialize Helm in the cluster.

kubectl create serviceaccount -n kube-system tiller

kubectl create clusterrolebinding tiller-cluster-rule --clusterrole=cluster-admin --serviceaccount=kube-system:tiller

helm init --service-account tiller

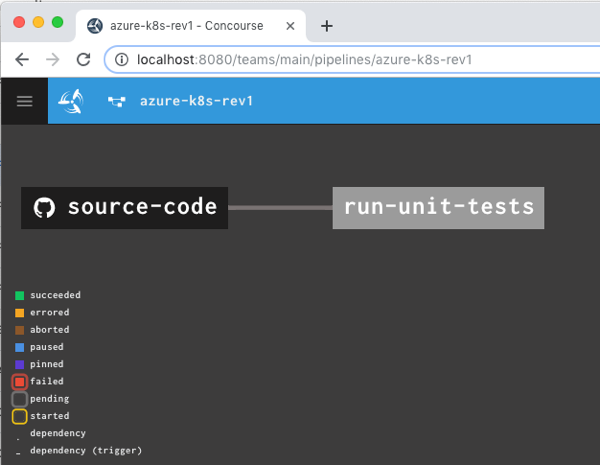

With that business behind me, I could install Concourse. I talk a lot about Concourse, taught a Pluralsight course about it, and use it regularly. It’s such a powerful tool for continuous processing of code. To install into Kubernetes, it’s just a single reference to a Helm chart.

helm install --name vmworld-concourse stable/concourse

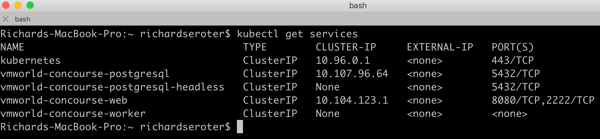

After a few moments, I saw that I had pods created and services configured.

The chart also printed out commands for how to do port forwarding to access the Concourse web console.

export POD_NAME=$(kubectl get pods --namespace default -l "app=vmworld-concourse-web" -o jsonpath="{.items[0].metadata.name}")

echo "Visit http://127.0.0.1:8080 to use Concourse"

kubectl port-forward --namespace default $POD_NAME 8080:8080

After running those commands, I pinged the localhost URL and saw the dashboard.

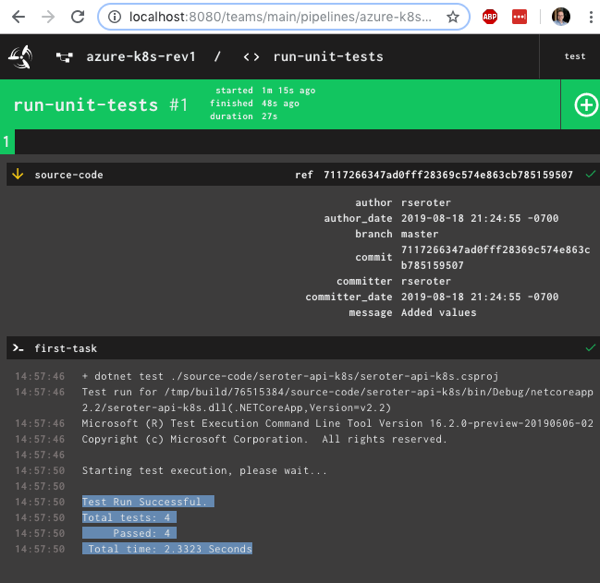

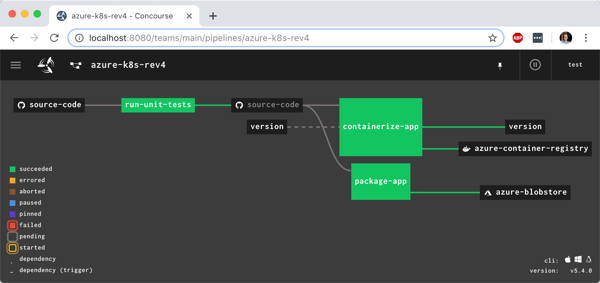

All that was left was the actual pipeline. Concourse pipelines are defined in YAML. My GitHub repo has two branches (master and stable), so I declared “resources” for both. Since I have to write to the stable branch, I also included credentials to GitHub in the “stable” resource definition. My pipeline has two jobs: one that runs the JUnit tests, and another puts the master branch code into the stable branch if the unit tests pass.

---

# declare resources

resources:

- name: source-master

type: git

icon: github-circle

source:

uri: https://github.com/rseroter/boot-kpack-demo

branch: master

- name: source-stable

type: git

icon: github-circle

source:

uri: git@github.com:rseroter/boot-kpack-demo.git

branch: stable

private_key: ((github-private-key))

jobs:

- name: run-tests

plan:

- get: source-master

trigger: true

- task: first-task

config:

platform: linux

image_resource:

type: docker-image

source: {repository: maven, tag: latest}

inputs:

- name: source-master

run:

path: sh

args:

- -exec

- |

cd source-master

mvn package

- name: promote-to-stable

plan:

- get: source-master

trigger: true

passed: [run-tests]

- get: source-stable

- put: source-stable

params:

repository: source-master

Deploying this pipeline is easy. From the fly CLI tool, it’s one command. Note that my GitHub creds are stored in another file, which is the one I reference in the command.

fly -t vmworld set-pipeline --pipeline vmworld-pipeline --config vmworld-pipeline.yaml --load-vars-from params.yaml

After unpausing the pipeline, it ran. Once it executed the unit tests, and promoted the master code to the stable branch, the pipeline was green.

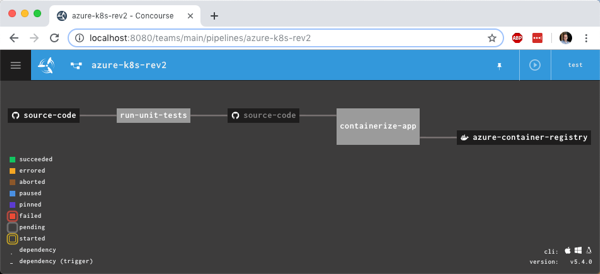

Step #3 – Set up kpack for container builds

Now to take that tested, high-quality code and containerize it. Cloud Native Buildpacks turn code into Docker images. Buildpacks are something initially created by Heroku, and then used by Cloud Foundry to algorithmically determine how to build a container image based on the language/framework of the code. Instead of developers figuring out how to layer up an image, buildpacks can compile and package up code in a repeatable way by bringing in all the necessary language runtimes and servers. What’s cool is that operators can also extend buildpacks to add org-specific certs, monitoring agents, or whatever else should be standard in your builds.

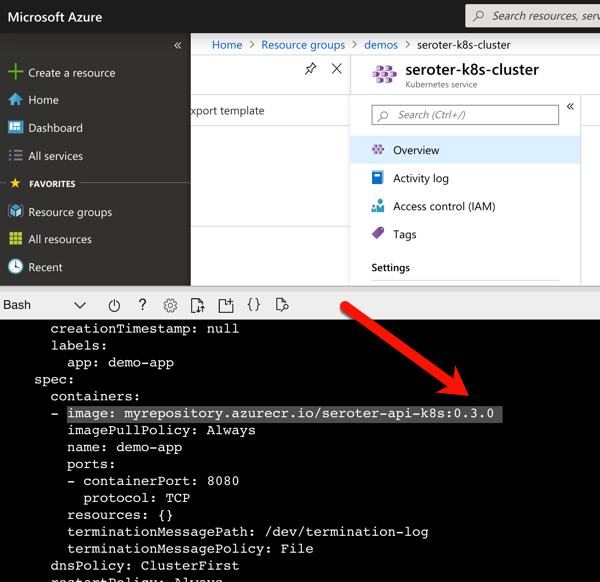

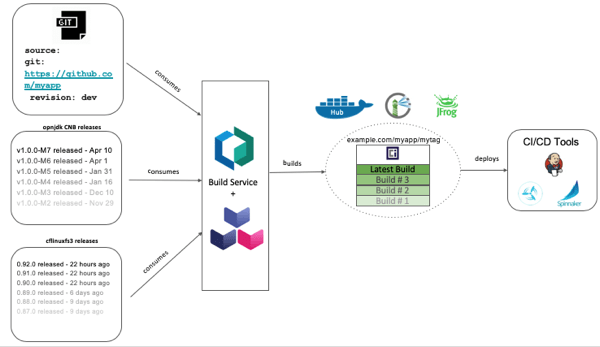

kpack is an open-source project from Pivotal that uses Cloud Native Buildpacks, also adds the ability to watch for changes to anything impacting the image, and initiating an update. kpack, which is commercialized as the Pivotal Build Service, watches for changes in source code, buildpacks, or base image and then puts the new or patched image into the registry. Thanks to some smarts, it only updates the impacted layers, thus saving you on data transfer costs and build times.

The installation instructions are fairly straightforward. You can put this into your Kubernetes cluster in a couple minutes. Once installed, I saw the single kpack controller pod running.

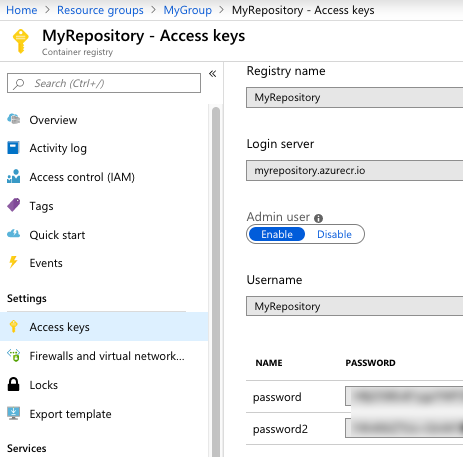

The only thing left to do was define an image configuration. This declarative config tells kpack where to find the code, and what to do with it. I had already set up a secret to hold my Docker Hub creds, and that corresponding Kubernetes service account is referenced in the image configuration.

apiVersion: build.pivotal.io/v1alpha1

kind: Image

metadata:

name: vmworld-image

spec:

tag: rseroter/vmworld-demo

serviceAccount: vmworld-service-account

builder:

name: default-builder

kind: ClusterBuilder

source:

git:

url: https://github.com/rseroter/boot-kpack-demo.git

revision: stable

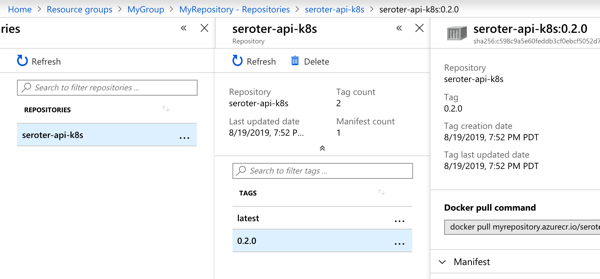

That’s it. Within moments, kpack detected my code repo, compiled my app, built a container image, cached some layers for later, and updated the Docker Hub image.

I made a bunch of code changes to generate lots of builds, and all the builds showed up my Kubernetes cluster as well.

Now when I updated my code, my pipeline automatically kicks off and updates the stable branch. Thus, whenever my tested code changes, or the buildpack gets updated (every week or so) with framework updates and patches, my container automatically gets rebuilt. That’s crazy powerful stuff, especially as we create more and more containers, that deploy to more and more places.

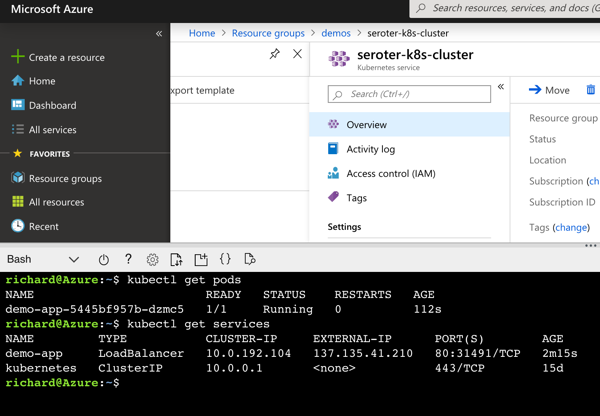

Step #4 – Deploy the container image

And that’s the final step. I had to deploy this sucker and see it run.

First, I pushed it to Pivotal Application Service (PAS) because I make good choices. I can push code or containers here. This single command takes that Docker image, deploys it, and gives me a routable endpoint in 20 seconds.

cf push vmworld-demo --docker-image rseroter/vmworld-demo -i 2

That worked great, and my endpoint returned the expected values after I added an environment variable to the app.

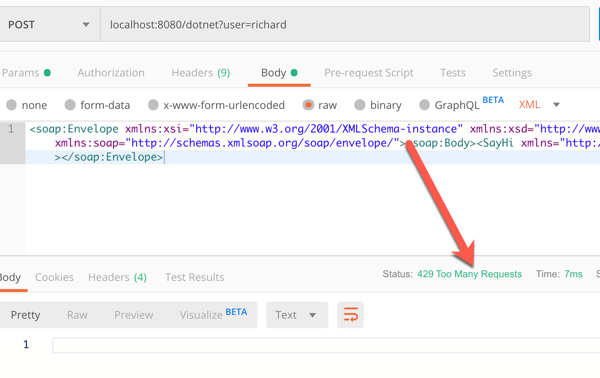

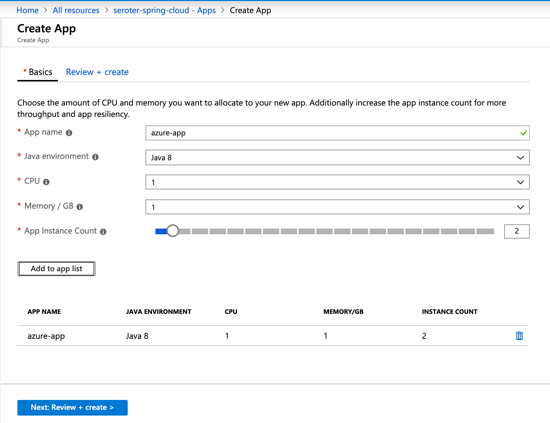

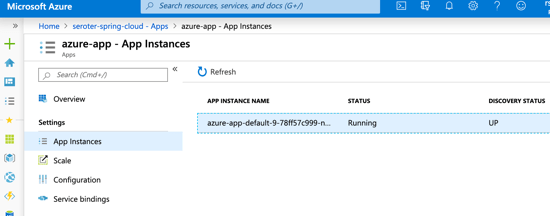

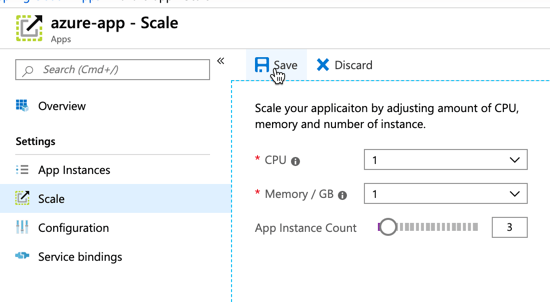

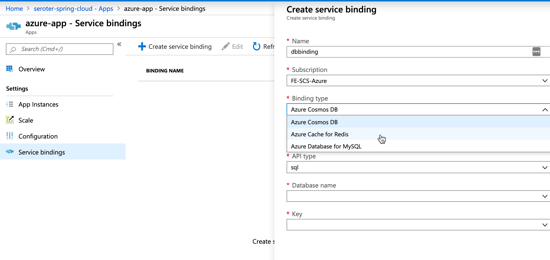

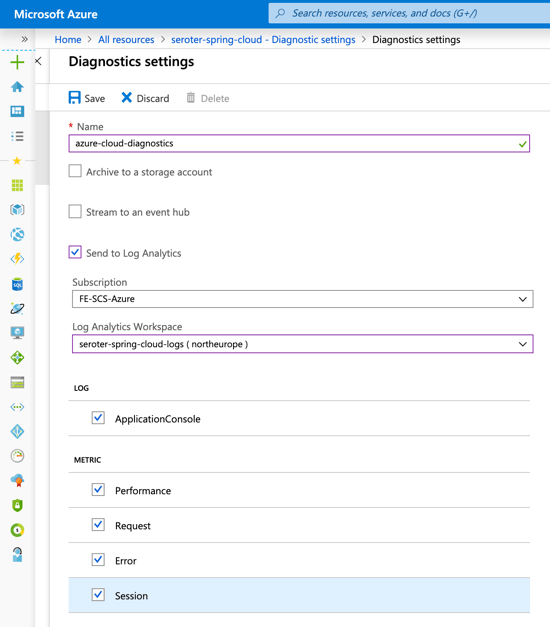

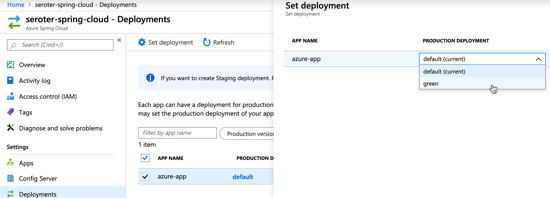

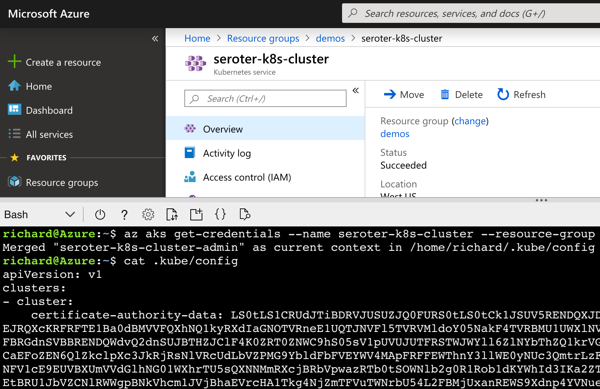

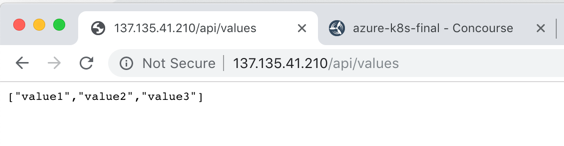

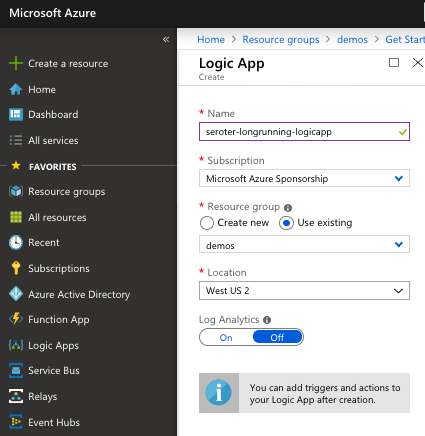

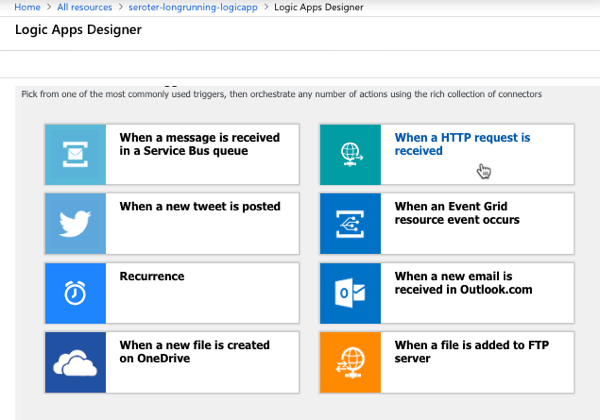

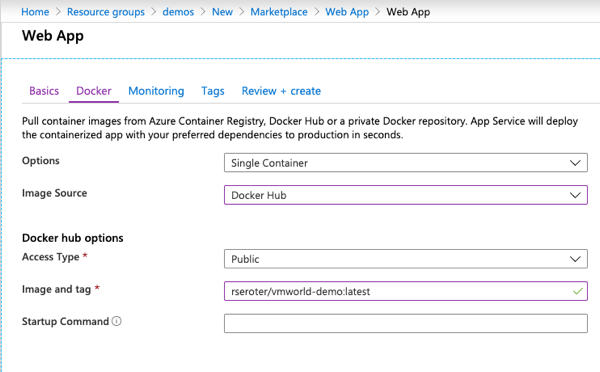

Can I deploy the same container to Azure Web Apps? Sure. That takes code or containers too. I walked through the wizard experience in the Azure Portal and chose the Docker Hub image created by kpack.

After a few minutes, the service was up. Then I set the environment variable that the Spring Boot app was looking for (appruntime to “Azure App Service”) and another to expose the right port (WEBSITES_PORT to 8080), and pinged the RESTful endpoint.

Whatever tech you land on, just promise me that you’ll invest in a container patching strategy. Automation is non-negotiable, and there are good solutions out there that can improve your security posture, while speeding up software delivery.