When my son was 3 years old, he would often get out of bed WAAAAY too early and want to play with me. I’d send him back to bed, and inevitably he’d check in again just a few minutes later. Eventually, we got him a clock with a timed light on it, so there was a clear trigger that it was time to get up.

Originally, my son was like a polling component that keeps asking “is it time yet?” I’ve built many of those myself in software. It’s a simple way to produce an event (“time to get up”, or “new order received”) when it’s the proper moment. But these pull-based approaches are remarkably inefficient and often return empty results until the time is right. Getting my son a clock that turned green when it was time to get out of bed is more like a push-based approach where the system tells you when something happened.

In software, there are legit reasons to do pull-based activities—maybe you intentionally want to batch the data retrieval and process it once a day—but it’s more common nowadays to see architects and developers embrace a push-driven event-based architecture that can operate in near real-time. Cloud platforms make this much easier to set up than it used to be with on-premises software!

I see three ways to activate events in your cloud architecture. Let’s look at examples of each.

Events automatically generated by service changes

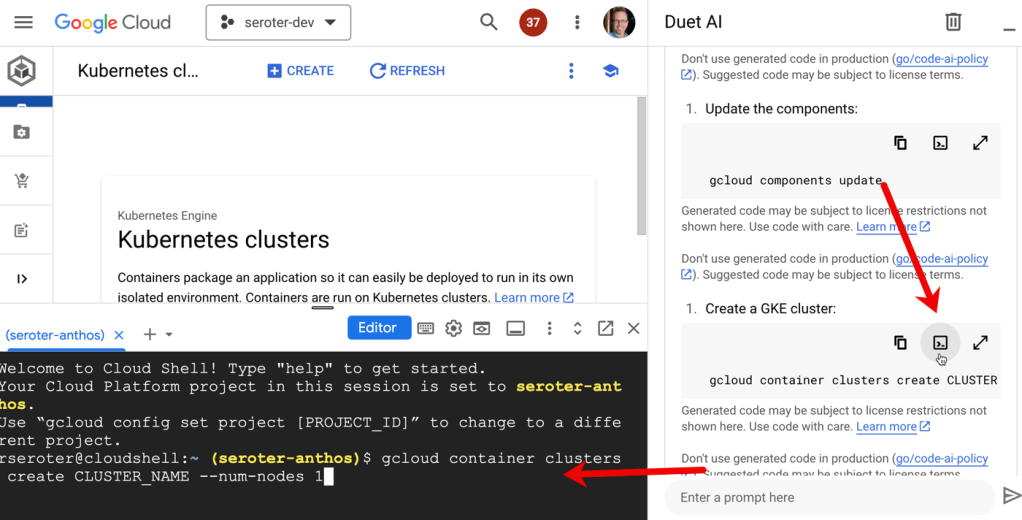

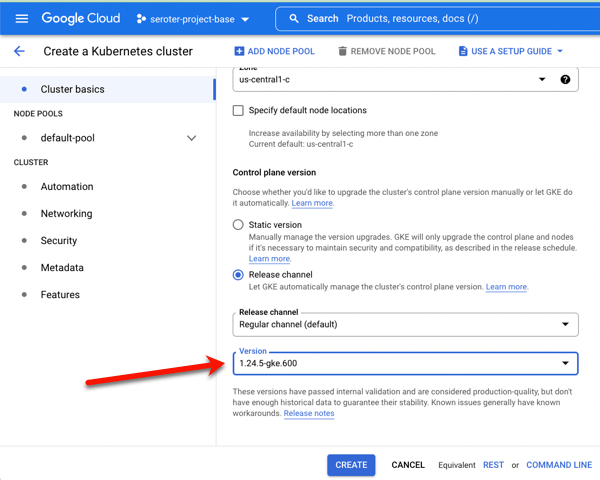

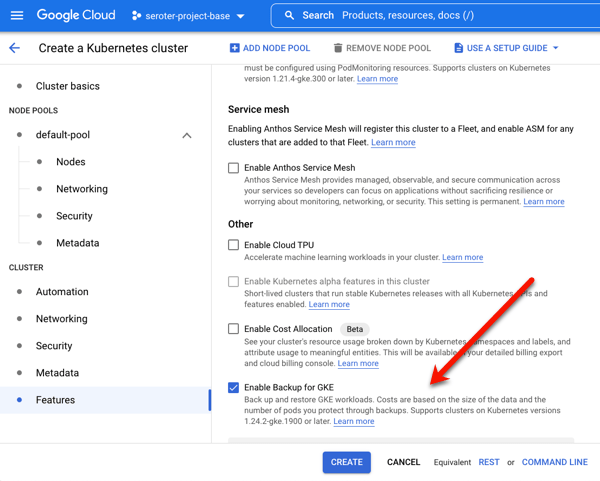

This is all about creating event when something happens to the cloud service. Did someone create a new IAM role? Build a Kubernetes cluster? Delete a database backup? Update a machine learning model?

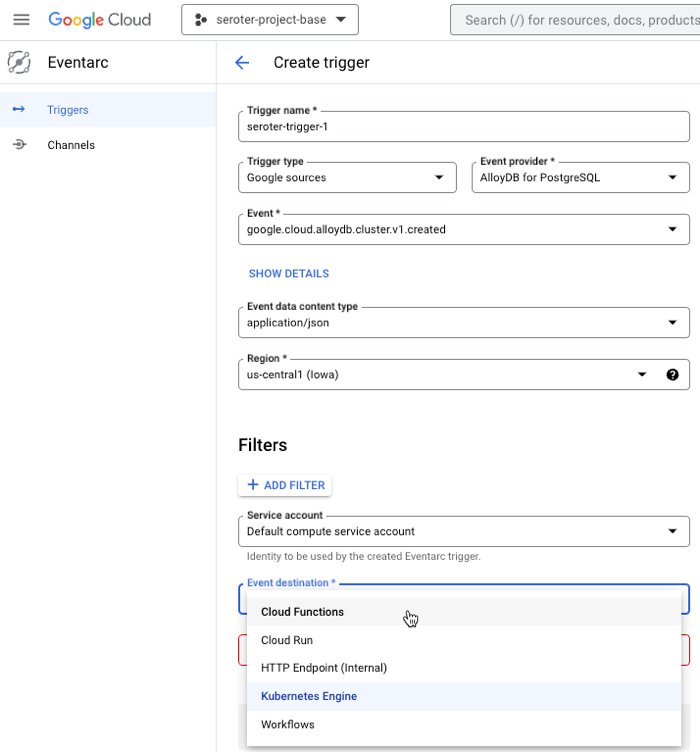

The major hyperscale cloud providers offer managed services that capture and route these events. AWS offers Amazon EventBridge, Microsoft gives you Azure Event Grid, and Google Cloud serves up Eventarc. Instead of creating your own polling component, retry logic, data schemas, observability system, and hosting infrastructure, you can use a fully managed end-to-end option in the cloud. Yes, please. Let’s look at doing this with Eventarc.

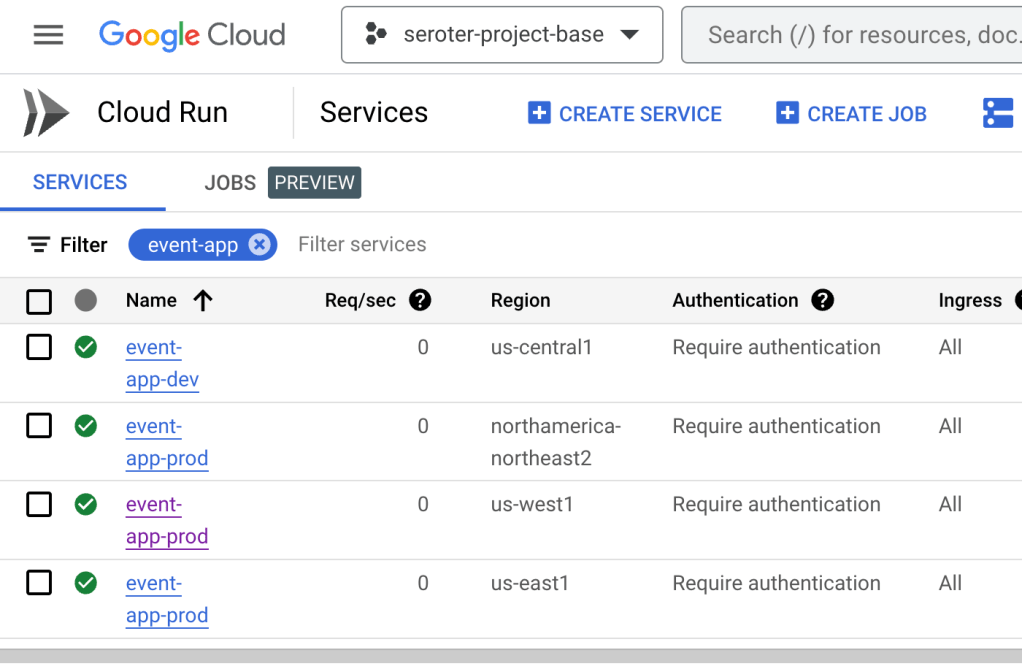

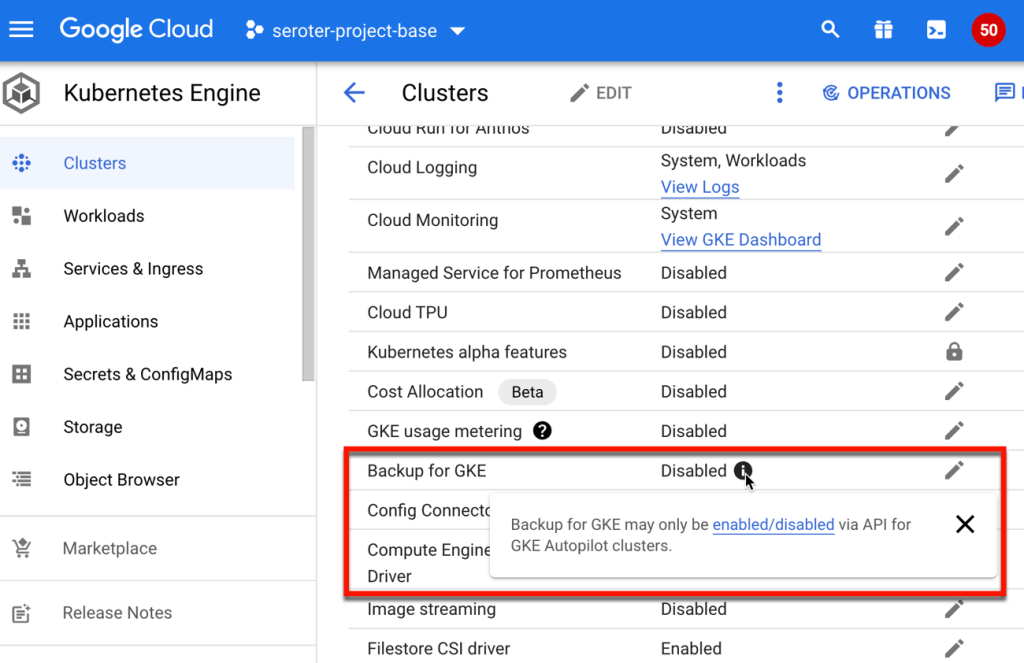

I can create triggers for most Google Cloud services, then choose among all the possible events for each service, provide any filters for what I’m looking for, and then choose a destination. Supported destinations for the routed event include serverless functions (Cloud Functions), serverless containers (Cloud Run), declarative workflow (Cloud Workflows), a Kubernetes service (GKE), or a random internal HTTP endpoint.

Starting here assumes I have a event destination pre-configured to receive the CloudEvents-encoded event. Let’s assume I don’t have anything in place to “catch” the event and need to create a new Cloud Function.

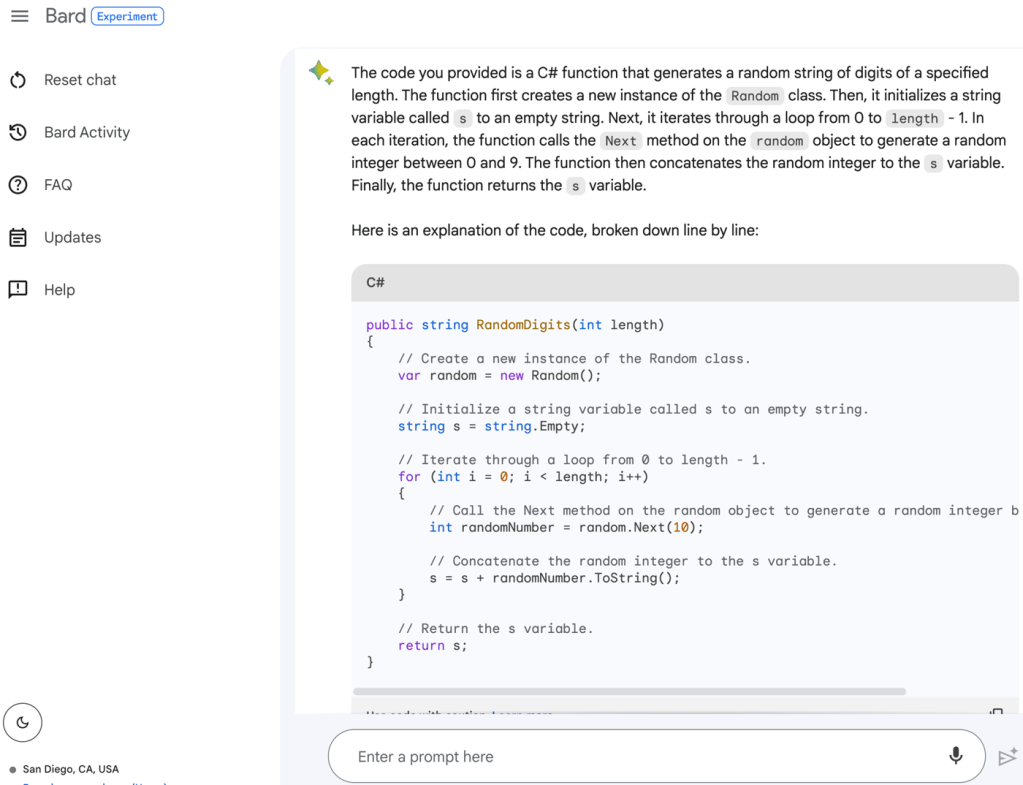

When I create a new Cloud Function, I have a choice of picking a non-HTTP trigger. This flys open an Eventarc pane where I follow the same steps as above. Here, I chose to catch the “enable service account” event for IAM.

Then I get function code that shows me how to read the key data from the CloudEvent payload. Handy!

Use these sorts of services to build loosely-coupled solutions to react to what’s going on in our cloud environment.

Events automatically generated by data changes

This is the category most of us are familiar with. Here, it’s about change data capture (CDC) that triggers an event based on new, updated, or deleted data in some data source.

Databases

Again, in most hyperscale clouds, you’ll find databases with CDC interfaces built in. I found three within Google Cloud: Cloud Spanner, Bigtable, and Firestore.

Cloud Spanner, our cloud-native relational database, offers change streams. You can “watch” an entire database, or narrow it down to specific tables or columns. Each data change record has the name of the affected table, the before-and-after data values, and a timestamp. We can read these change streams within our Dataflow product, calling the Spanner API, or using the Kafka connector. Learn more here.

Bigtable, our key-value database service, also supports change streams. Every data change record contains a bunch of relevant metadata, but does not contain the “old” value of the database record. Similar to Spanner, you can read Bigtable change streams using Dataflow or the Java client library. Learn more here.

Firestore is our NoSQL cloud database that’s often associated with the Firebase platform. This database has a feature to create listeners on a particular document or document collection. It’s different from the previous options, and looks like it’s mostly something you’d call from code. Learn more here.

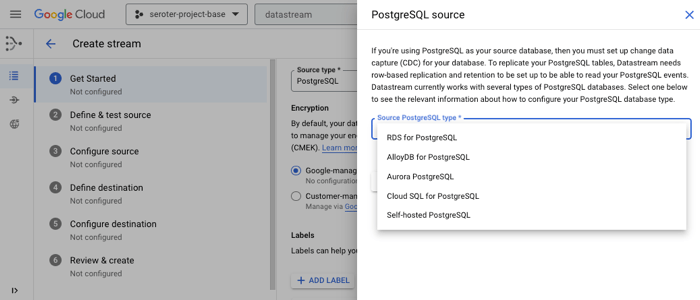

Some of our other databases like Cloud SQL support CDC using their native database engine (e.g. SQL Server), or can leverage our manage change data capture service called Datastream. Datastream pulls from PostgreSQL, MySQL, and Oracle data sources and publishes real-time changes to storage or analytical destinations.

“Other” services

There is plenty of “data” in systems that aren’t “databases.” What if you want events from those? I looked through Google Cloud services and saw many others that can automatically send change events to Google Cloud Pub/Sub (our message broker) that you can then subscribe to. Some of these look like a mix of the first category (notifications about a service) and this category (notifications about data in the service):

- Cloud Storage. When objects change in Cloud Storage, you can send notifications to Pub/Sub. The payload contains info about the type of event, the bucket ID, and the name of the object itself.

- Cloud Build. Whenever your build state changes in Cloud Build (our CI engine), you can have a message sent to Pub/Sub. These events go to a fixed topic called “cloud-builds” and the event message holds a JSON version of your build resource. You can configure either push or pull subscriptions for these messages.

- Artifact Registry. Want to set up an event for changes to Docker repositories? You can get messages for image uploads, new tags, or image deletions. Here’s how to set it up.

- Artifact Analysis. This package scanning tool look for vulnerabilities, and you can send notifications to Pub/Sub when vulnerabilities are discovered. The simple payloads tell you what happened, and when.

- Cloud Deploy. Our continuous deployment tool also offers notifications about changes to resources (rollouts, pipelines), when approvals are needed, or when a pipeline is advancing phases. It can be handy to use these notifications to kick off further stages in your workflows.

- GKE. Our managed Kubernetes service also offers automatic notifications. These apply at the cluster level versus events about individual workloads. But you can get events about security bulletins for the cluster, new GKE versions, and more.

- Cloud Monitoring Alerts. Our built-in monitoring service can send alerts to all sorts of notification channels including email, PagerDuty, SMS, Slack, Google Chat, and yes, Pub/Sub. It’s useful to have metric alert events routing through your messaging system, and you can see how to configure that here.

- Healthcare API. This capability isn’t just for general-purpose cloud services. We offer a rich API for ingesting, storing, analyzing, and integrating healthcare data. You can set up automatic events for FHIR, HL7 resources, and more. You get metadata attributes and an identifier for the data record.

And there are likely other services I missed! Many cloud services have built-in triggers that route events to downstream components in your architecture.

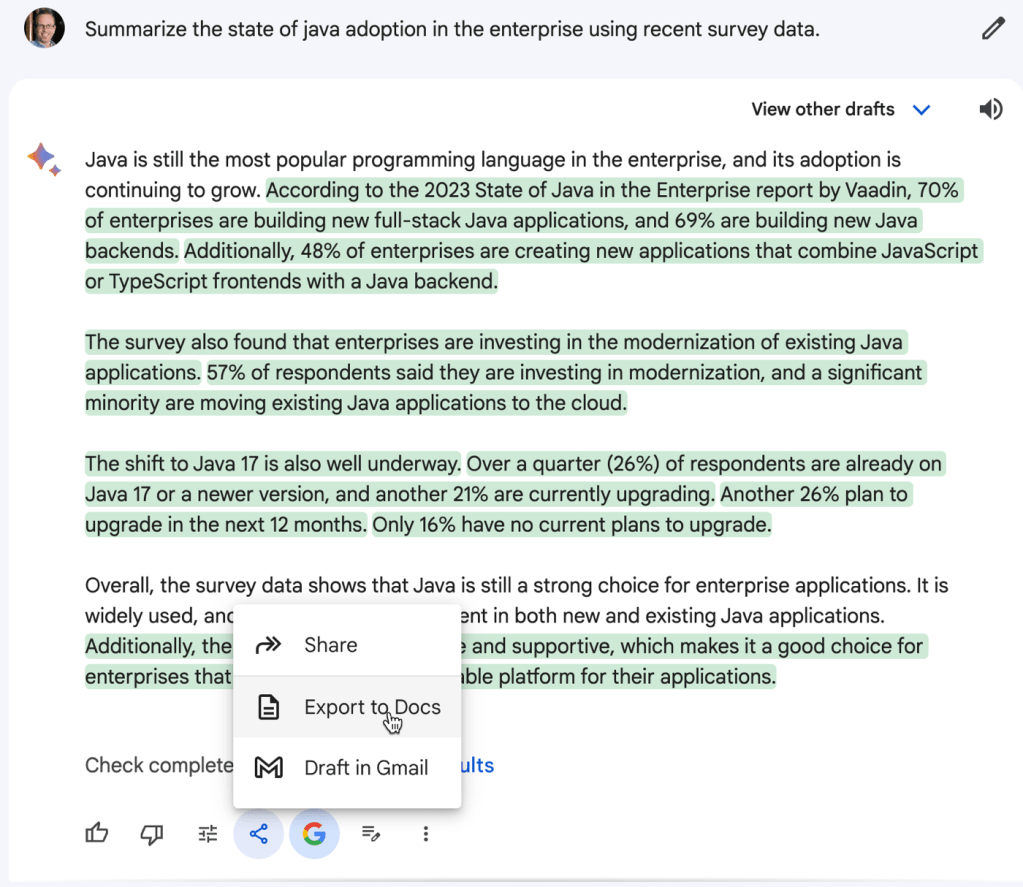

Events manually generated by code or DIY orchestration

Sometimes you need fine-grained control for generating events. You might use code or services to generate and publish events.

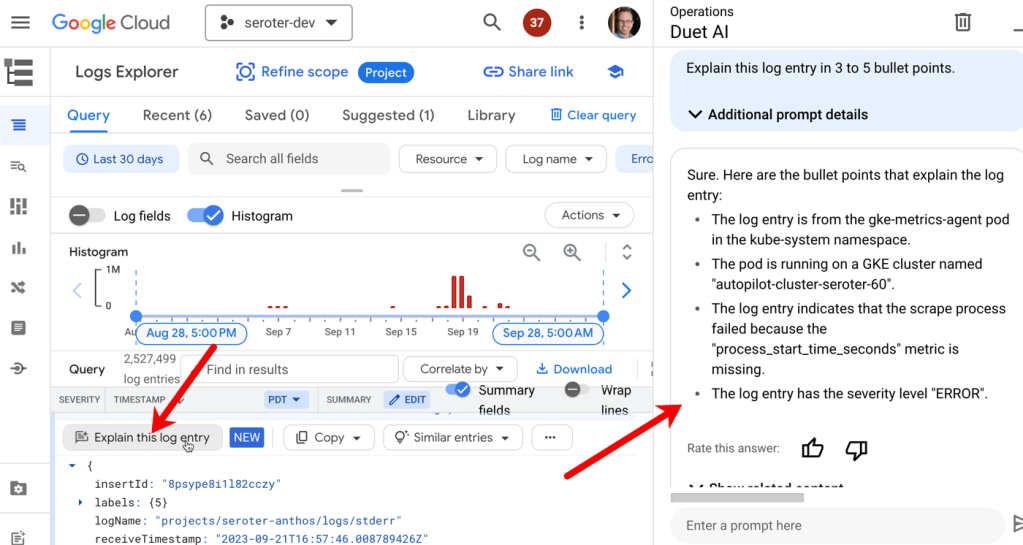

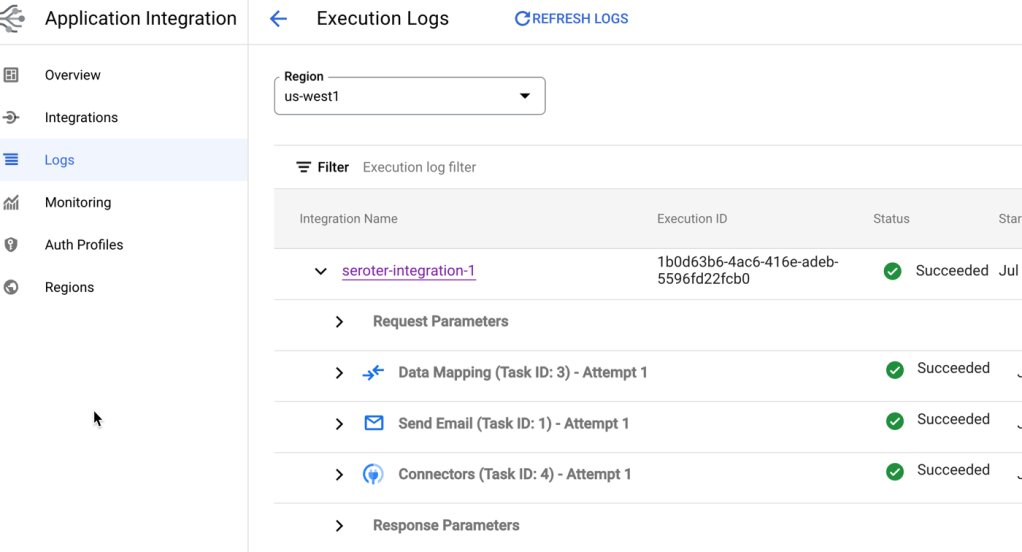

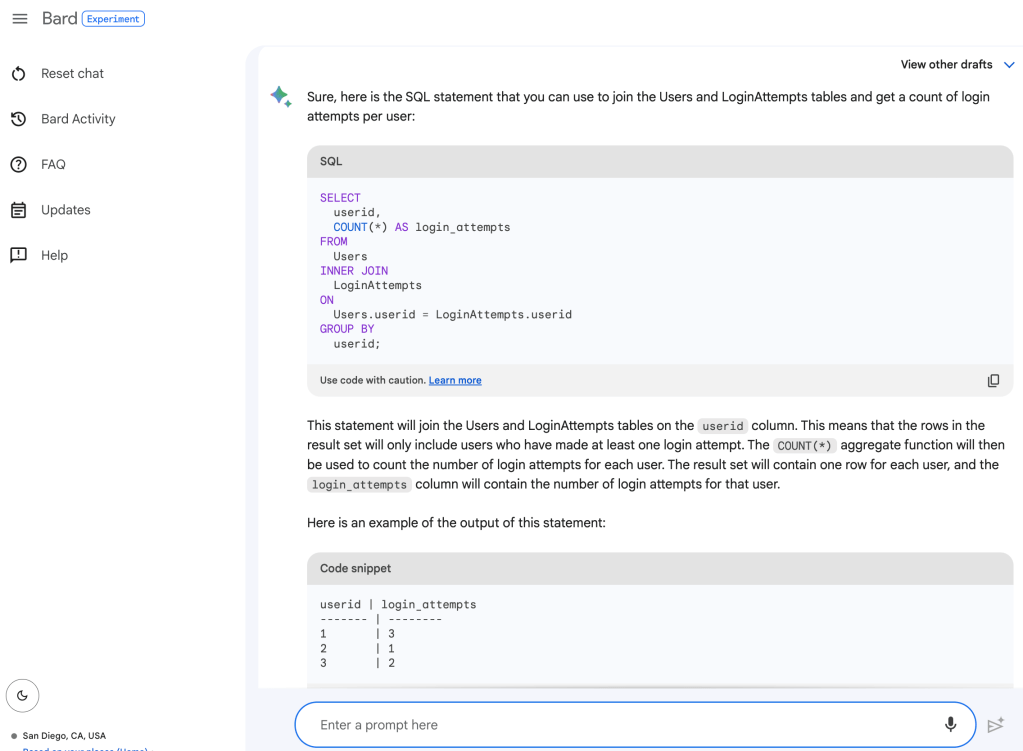

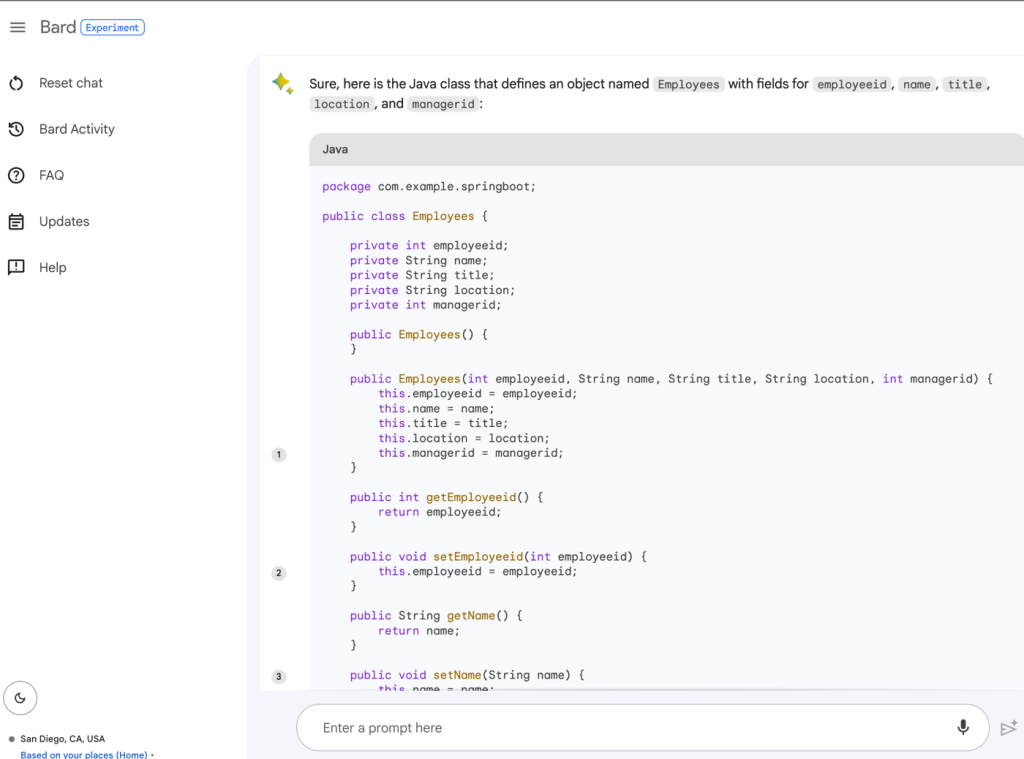

First, you may wire up managed services to do your work. Maybe you use Azure Logic Apps or Google Cloud App Integration to schedule a database poll every hour, and then route any relevant database records as individual events. Or you use a data processing engine like Google Cloud Dataflow to generate batch or real-time messages from data sources into Pub/Sub or another data destination. And of course, you may use third-party integration platform that retrieve data from services and generates events.

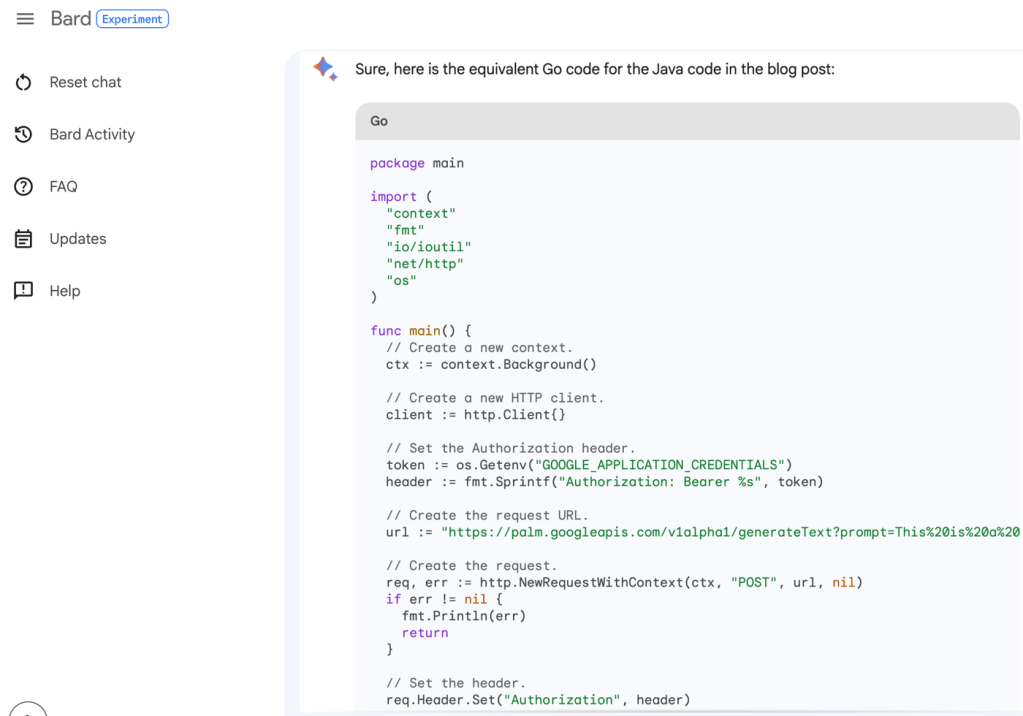

Secondly, you may hand-craft an event in your code. Your app could generate events when specific things happen in your business logic. Every cloud offers a managed messaging service, and you can always send events from your code to best-of-breed products like RabbitMQ, Apache Kafka, or NATS.

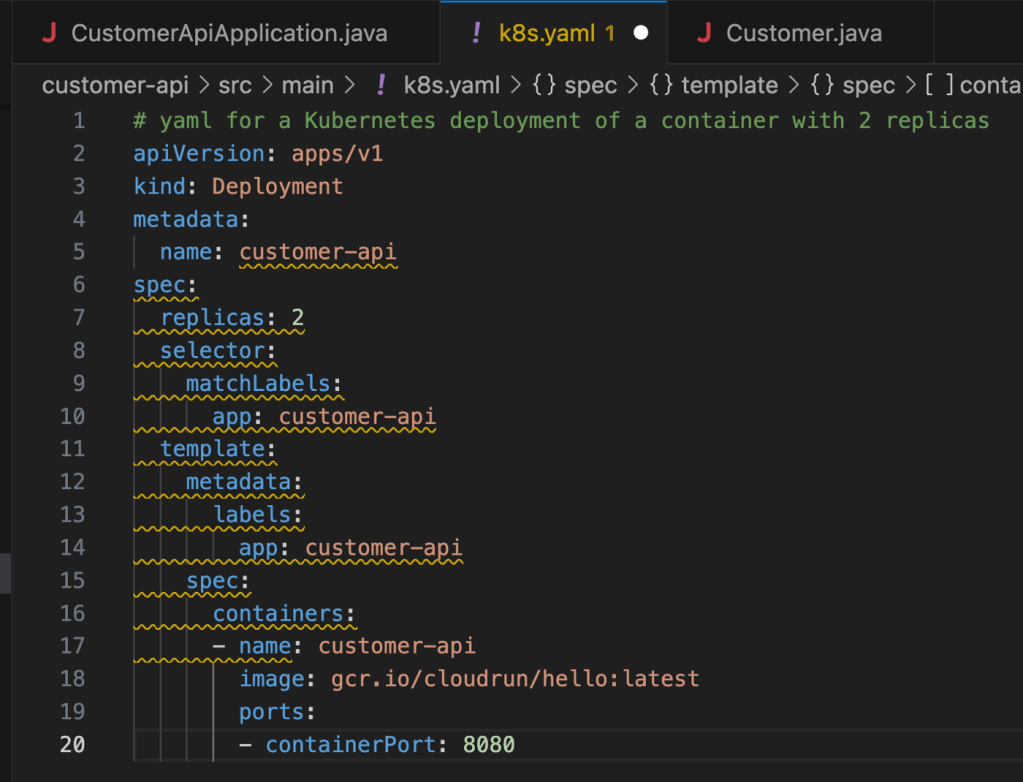

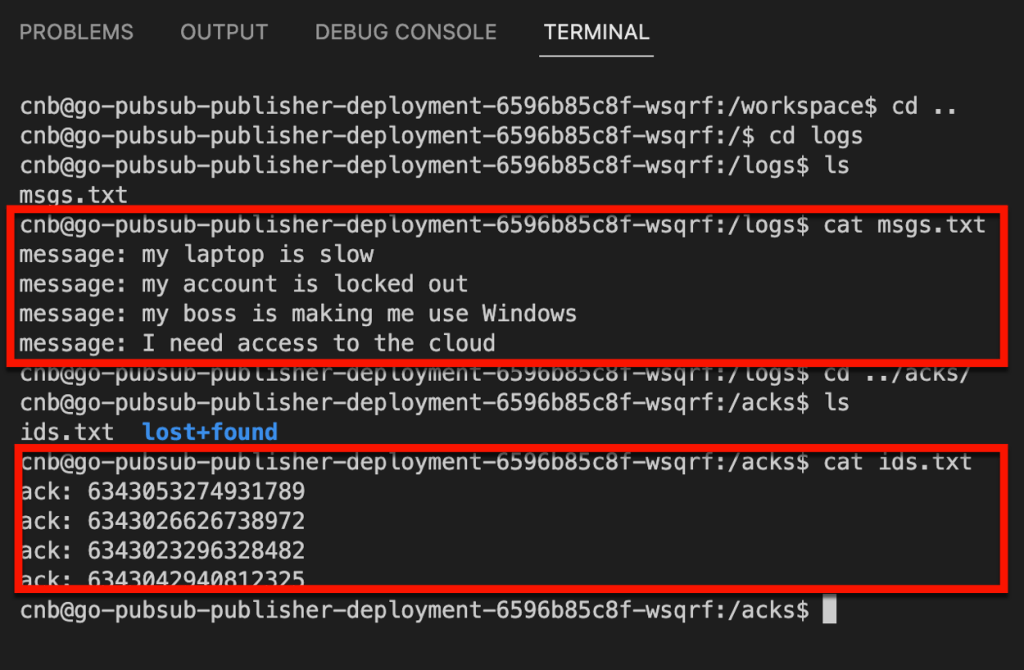

In this short example, I’m generating an event from within a Google Cloud Function and sending it to Pub/Sub. BTW, since Cloud Functions and Pub/Sub both have generous free tiers, you can follow along at no cost.

I created a brand new function and chose Node.js 20 as my language/framework. I added a single reference to the package.json file:

"@google-cloud/pubsub": "4.0.7"

Then I updated the default index.js code with a reference to the pubsub package, and added code to publish the incoming querystring value as an event to Pub/Sub.

const functions = require('@google-cloud/functions-framework');

const {PubSub} = require('@google-cloud/pubsub');

functions.http('helloHttp', (req, res) => {

var projectId = 'seroter-project-base';

var topicNameOrId = 'custom-event-router';

// Instantiates a client

const pubsub = new PubSub({projectId});

const topic = pubsub.topic(topicNameOrId);

// Send a message to the topic

topic.publishMessage({data: Buffer.from('Test message from ' + req.query.name)});

// return result

res.send(`Hello ${req.query.name || req.body.name || 'World'}!`);

});

That’s it. Once I deployed the function and called the endpoint with a querystring, I saw all the messages show up in Pub/Sub, ready to be consumed.

Wrap

Creating and processing events using managed services in the cloud is powerful. It can both simplify and complicate your architecture. It can make it simpler by getting rid of all the machinery to poll and process data from your data sources. Events make your architecture more dynamic and reactive. And that’s where it can get more complicated if you’re not careful. Instead of a clumsy, but predictable set of code that pulls data and processes it inline, now you might have a handful of loosely-coupled components that are lightly orchestrated. Do what makes sense, versus what sounds exciting!