I rarely enjoy the last mile of work. Sure, there’s pleasure in seeing something reach its conclusion, but when I’m close, I just want to be done! For instance, when I create a Pluralsight course—my new one, Cloud Foundry: The Big Picture just came out—I enjoy the building part, and dread the record+edit portion. Same with writing software. I like coding an app to solve a problem. Then, I want a fast deployment so that I can see how the app works, and wrap up. Ideally, each app I write doesn’t require a unique set of machinery or know-how. Thus, I wanted to see if I could create a *single* Google Cloud Build deployment pipeline that shipped any custom app to the serverless Google Cloud Run environment.

Cloud Build is Google Cloud’s continuous integration and delivery service. It reminds me of Concourse in that it’s declarative, container-based, and lightweight. It’s straightforward to build containers or non-container artifacts, and deploy to VMs, Kubernetes, and more. The fact that it’s a hosted service with a great free tier is a bonus. To run my app, I don’t want to deal with configuring any infrastructure, so I chose Google Cloud Run as my runtime. It just takes a container image and offers a fully-managed, scale-to-zero host. Before getting fancy with buildpacks, I wanted to learn how to use Build and Run to package up and deploy a Spring Boot application.

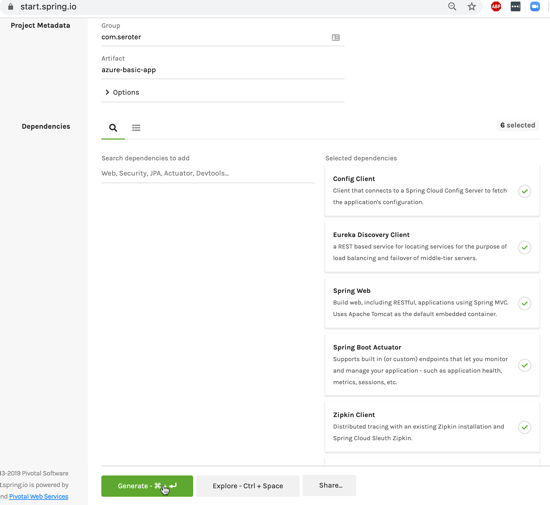

First, I generated a new Spring Boot app from start.spring.io. It’s going to be a basic REST API, so all I needed was the Web dependency.

I’m not splitting the atom with this Java code. It simply returns a greeting when you hit the root endpoint.

@RestController

@SpringBootApplication

public class HelloAppApplication {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(HelloAppApplication.class, args);

}

@GetMapping("/")

public String SayHello() {

return "Hi, Google Cloud Run!";

}

}

Now, I wanted to create a pipeline that packaged up the Boot app into a JAR file, built a Docker image, and deployed that image to Cloud Run. Before crafting the pipeline file, I needed a Dockerfile. This file offers instructions on how to assemble the image. Here’s my basic one:

FROM openjdk:11-jdk

ARG JAR_FILE=target/hello-app-0.0.1-SNAPSHOT.jar

COPY ${JAR_FILE} app.jar

ENTRYPOINT ["java", "-Djava.security.edg=file:/dev/./urandom","-jar","/app.jar"]

On to the pipeline. A build configuration isn’t hard to understand. It consists of a series of sequential or parallel steps that produce an outcome. Each step runs in its own container image (specified in the name attribute), and if needed, there’s a simple way to transfer state between steps. My cloudbuild.yaml file for this Spring Boot app looked like this:

steps:

# build the Java app and package it into a jar

- name: maven:3-jdk-11

entrypoint: mvn

args: ["package", "-Dmaven.test.skip=true"]

# use the Dockerfile to create a container image

- name: gcr.io/cloud-builders/docker

args: ["build", "-t", "gcr.io/$PROJECT_ID/hello-app", "--build-arg=JAR_FILE=target/hello-app-0.0.1-SNAPSHOT.jar", "."]

# push the container image to the Registry

- name: gcr.io/cloud-builders/docker

args: ["push", "gcr.io/$PROJECT_ID/hello-app"]

#deploy to Google Cloud Run

- name: 'gcr.io/cloud-builders/gcloud'

args: ['run', 'deploy', 'seroter-hello-app', '--image', 'gcr.io/$PROJECT_ID/hello-app', '--region', 'us-west1', '--platform', 'managed']

images: ["gcr.io/$PROJECT_ID/hello-app"]

You’ll notice four steps. The first uses the Maven image to package my application. The result of that is a JAR file. The second step uses a Docker image that’s capable of generating an image using the Dockerfile I created earlier. The third step pushes that image to the Container Registry. The final step deploys the container image to Google Cloud Run with an app name of seroter-hello-app. The final “images” property puts the image name in my Build results.

As you can imagine, I can configure triggers for this pipeline (based on code changes, etc), or execute it manually. I’ll do the latter, as I haven’t stored this code in a repository anywhere yet. Using the terrific gcloud CLI tool, I issued a single command to kick off the build.

gcloud builds submit --config cloudbuild.yaml .

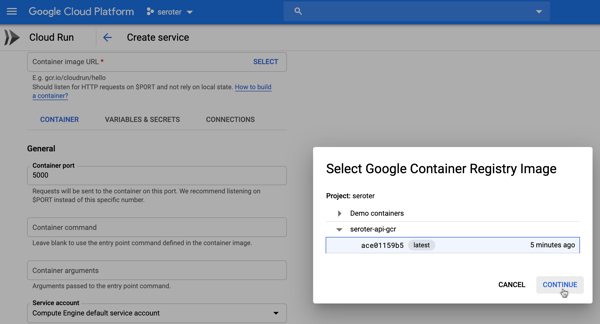

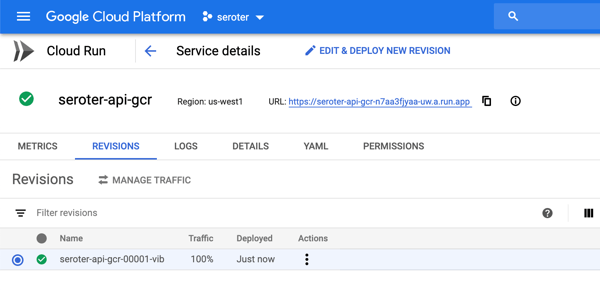

After a minute or so, I have a container image in the Container Registry, an available endpoint in Cloud Run, and a full audit log in Cloud Build.

Container Registry:

Cloud Run (with indicator that app was deployed via Cloud Build:

Cloud Build:

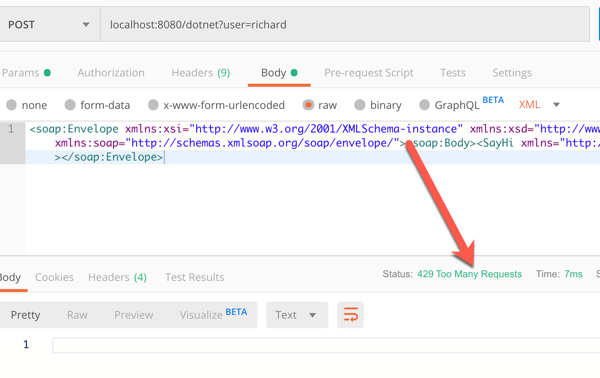

I didn’t expose the app publicly, so to call it, I needed to authenticate myself. I used the “gcloud auth print-identity-token” command to get a Bearer token, and plugged that into the Authorization header in Postman. As you’d expect, it worked. And when traffic dies down, the app scales to zero and costs me nothing.

So this was great. I did all this without having to install build infrastructure, or set up an application host. But I wanted to go a step further. Could I eliminate the Dockerization portion? I have zero trust in myself to build a good image. This is where buildpacks come in. They generate well-crafted, secure container images from source code. Google created a handful of these using the CNCF spec, and we can use them here.

My new cloudbuild.yaml file looks like this. See that I’ve removed the steps to package the Java app, and build and push the Docker image, and replaced them with a single “pack” step.

steps:

# use Buildpacks to create a container image

- name: 'gcr.io/k8s-skaffold/pack'

entrypoint: 'pack'

args: ['build', '--builder=gcr.io/buildpacks/builder', '--publish', 'gcr.io/$PROJECT_ID/hello-app-bp:$COMMIT_SHA']

#deploy to Google Cloud Run

- name: 'gcr.io/cloud-builders/gcloud'

args: ['run', 'deploy', 'seroter-hello-app-bp', '--image', 'gcr.io/$PROJECT_ID/hello-app-bp:latest', '--region', 'us-west1', '--platform', 'managed']

With the same gcloud command (gcloud builds submit --config cloudbuild.yaml .) I kicked off a new build. This time, the streaming logs showed me that the buildpack built the JAR file, pulled in a known-good base container image, and containerized the app. The result: a new image in the Registry (21% smaller in size, by the way), and a fresh service in Cloud Run.

I started out this blog post saying that I wanted a single cloudbuild.yaml file for *any* app. With Buildpacks, that seemed possible. The final step? Tokenizing the build configuration. Cloud Build supports “substitutions” which lets you offer run-time values for variables in the configuration. I changed my build configuration above to strip out the hard-coded names for the image, region, and app name.

steps:

# use Buildpacks to create a container image

- name: 'gcr.io/k8s-skaffold/pack'

entrypoint: 'pack'

args: ['build', '--builder=gcr.io/buildpacks/builder', '--publish', 'gcr.io/$PROJECT_ID/$_IMAGE_NAME:$COMMIT_SHA']

#deploy to Google Cloud Run

- name: 'gcr.io/cloud-builders/gcloud'

args: ['run', 'deploy', '$_RUN_APPNAME', '--image', 'gcr.io/$PROJECT_ID/$_IMAGE_NAME:latest', '--region', '$_REGION', '--platform', 'managed']

Before trying this with a new app, I tried this once more with my Spring Boot app. For good measure, I changed the source code so that I could confirm that I was getting a fresh build. My gcloud command now passed in values for the variables:

gcloud builds submit --config cloudbuild.yaml . --substitutions=_IMAGE_NAME="hello-app-bp",_RUN_APPNAME="seroter-hello-app-bp",_REGION="us-west1"

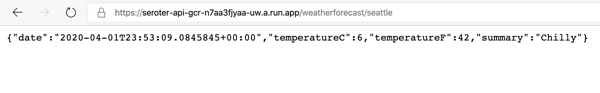

After a minute, the deployment succeeded, and when I called the endpoint, I saw the updated API result.

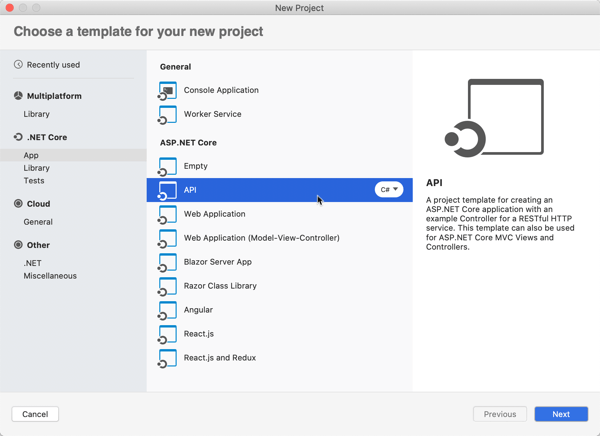

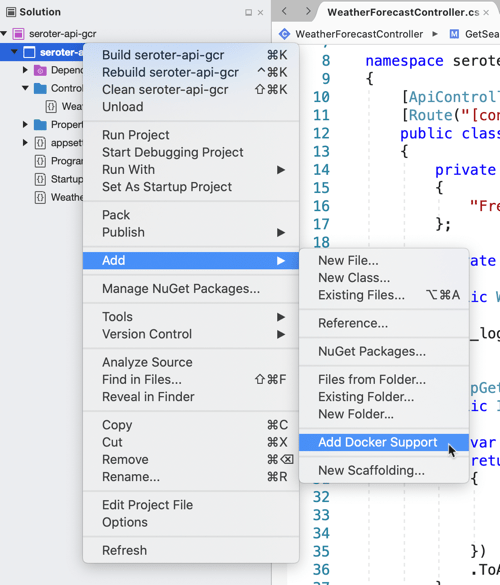

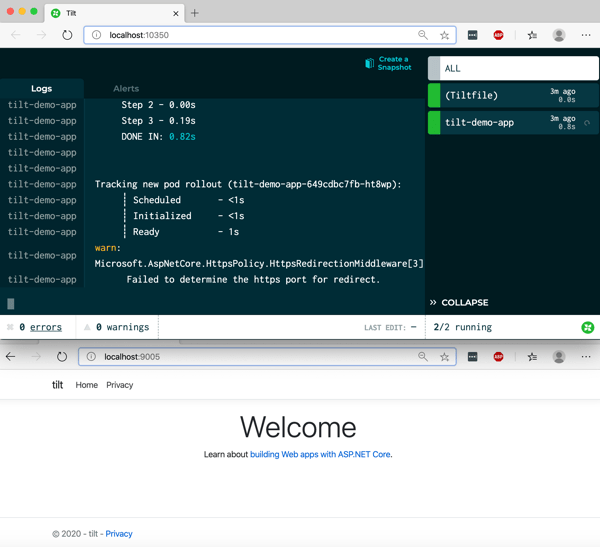

For the grand finale, I want to take this exact file, and put it alongside a newly built ASP.NET Core app. I did a simple “dotnet new webapi” and dropped the cloudbuild.yaml file into the project folder.

After tweaking the Program.cs file to read the application port from the platform-provided environment variable, I ran the following command:

gcloud builds submit --config cloudbuild.yaml . --substitutions=_IMAGE_NAME="hello-app-core",_RUN_APPNAME="seroter-hello-app-core",_REGION="us-west1"

A few moments later, I had a container image built, and my ASP.NET Core app listening to requests in Cloud Run.

Calling that endpoint (with authentication) gave me the API results I expected.

Super cool. So to recap, that six line build configuration above works for your Java, .NET Core, Python, Node, and Go apps. It’ll create a secure container image that works anywhere. And if you use Cloud Build and Cloud Run, you can do all of this with no mess. I might actually start enjoying the last mile of app development with this setup.