Coordination in distributed systems is hard. How do a series of networked processes share information and stay in sync with each other? Recently, the RabbitMQ team released a new type of queue that uses the Raft Consensus Algorithm to offer a durable, first-in-first-out queuing experience in your cluster. This is a nice fit for scenarios where you can’t afford data loss, and you also want the high availability offered by a clustered environment. Since RabbitMQ is wildly popular and used all over the place, I thought it’d be fun to dig into quorum queues, and give you an example that you can follow along with.

What do you need on your machine to follow along? Make sure you have Docker Desktop, or some way to instantiate containers from a Docker Compose file. And you should have git installed. You COULD stop there, but I’m also building a small pair of apps (publisher, subscriber) in Spring Boot. To do that part, ensure you have the JDK installed, and an IDE (Eclipse or IntelliJ) or code editor (like VS Code with Java + Boot extensions) handy. That’s it.

Before we start, a word about quorum queues. They shipped as part of a big RabbitMQ 3.8 release in the Fall of 2019. Quorum queues are the successor to mirrored queues, and improve on them in a handful of ways. By default, queues are located on a single node in a cluster. Obviously something that sits on a single node is at risk of downtime! So, we mitigate that risk by creating clusters. Mirrored queues have a master node, and mirrors across secondary nodes in the cluster for high availability. If a master fails, one of the mirrors gets promoted and processing continues. My new colleague Jack has a great post on how quorum queues “fix” some of the synchronization and storage challenges with mirrored queues. They’re a nice improvement, which is why I wanted to explore them a bit.

Let’s get going. First, we need to get a RabbitMQ cluster up and running. Thanks to containers, this is easy. And thanks to the RabbitMQ team, it’s super easy. Just git clone the following repo:

git clone https://github.com/rabbitmq/rabbitmq-prometheus

In that repo are Docker Compose files. The one we care about is in the docker folder and called docker-compose-qq.yml. In here, you’ll see a network defined, and some volumes and services. This setup creates a three node RabbitMQ cluster. If you run this right now (docker-compose -f docker/docker-compose-qq.yml up) you’re kind of done (but don’t stop here!). The final service outlined in the Compose file (qq-moderate-load) creates some queues for you, and generates some load, as seen below in the RabbitMQ administration console.

You can see above that the queue I selected is a “quorum” queue, and that there’s a leader of the queue and multiple online members. If I deleted that leader node, the messaging traffic would continue uninterrupted and a new leader would get “elected.”

I don’t want everything done for me, so after cleaning up my environment (docker-compose -f docker/docker-compose-qq.yml down), I deleted the qq-moderate-load service definition from my Docker Compose file, and renamed it. Then I spun it up again, with the new file name:

docker-compose -f docker/docker-compose-qq-2.yml up

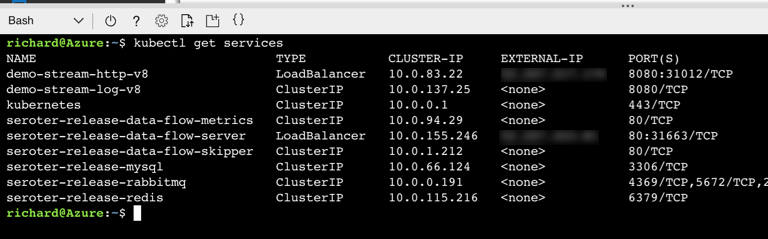

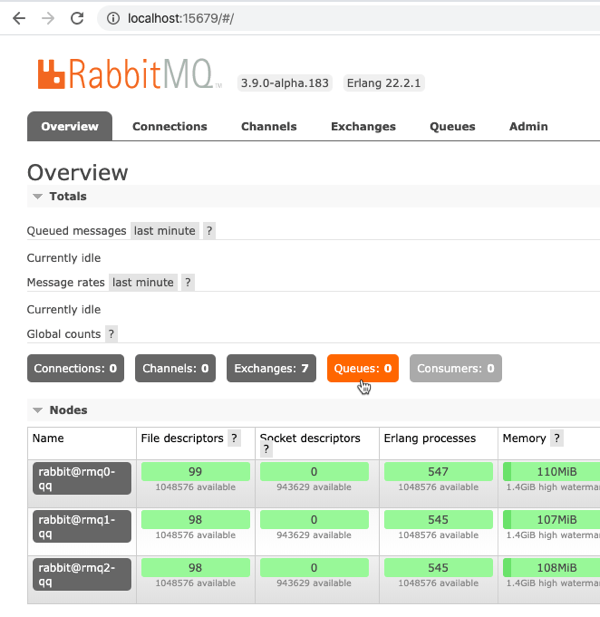

We now have an “empty” RabbitMQ, with three nodes in the cluster, but no queues or exchanges.

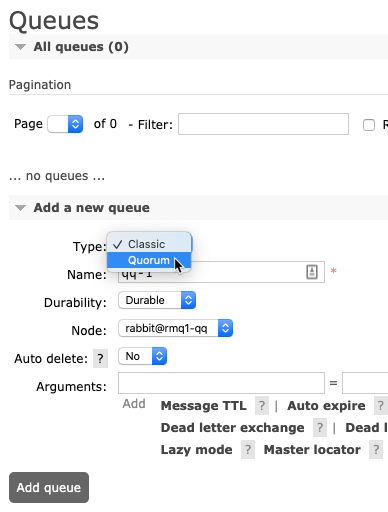

Let’s create a quorum queue. On the “Queues” tab of this administration console, fill in a name for the new queue (I called mine qq-1), select quorum as the type, and pick a node to set as the leader. I picked rmq1-qq. Click the “Add queue” button.

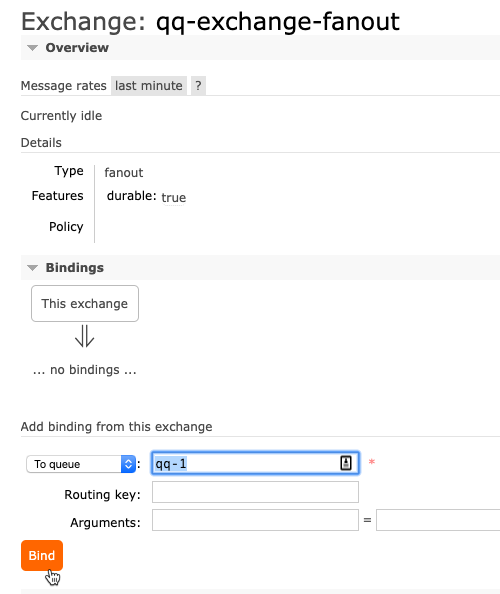

Now we need an exchange, which is the publisher-facing interface. Create a fanout exchange named qq-exchange-fanout and then bind our queue to this exchange.

Ok, that’s it for RabbitMQ. We have a highly available queue stood up with replication across three total nodes. Sweet. Now, we need an app to publish messages to the exchange.

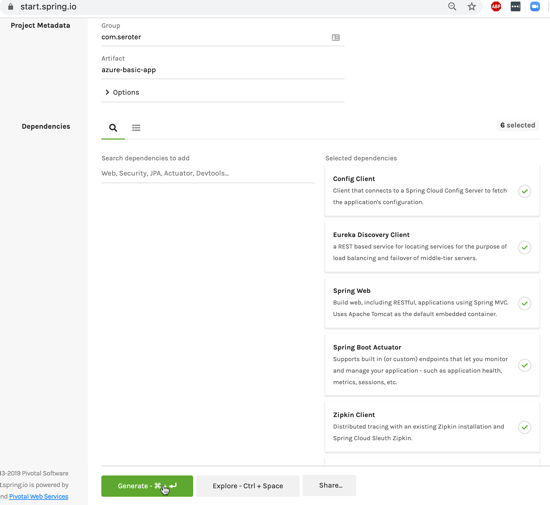

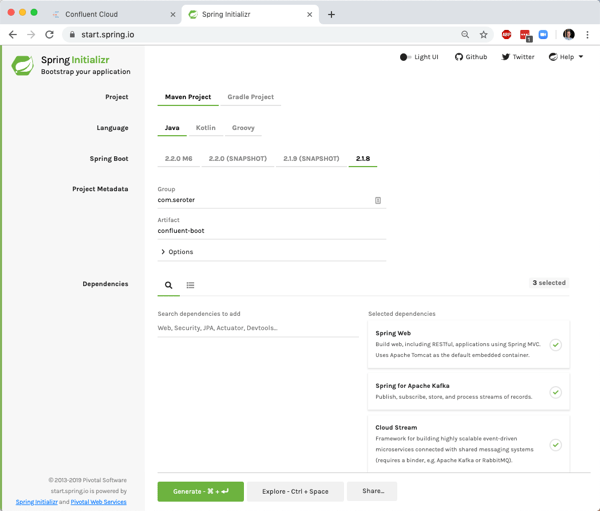

I went to start.spring.io to generate a Spring Boot project. You can talk to RabbitMQ from virtually any language, using any number of supported SDKs. This link gives you a Spring Boot project identical to mine.

I included dependencies on Spring Cloud Stream and Spring for RabbitMQ. These packages inflate all the objects necessary to talk to RabbitMQ, without forcing my code to know anything about RabbitMQ itself.

Two words to describe my code? Production Grade. Here’s all I needed to write to publish a message every 500ms.

package com.seroter.demo;

import org.springframework.boot.SpringApplication;

import org.springframework.boot.autoconfigure.SpringBootApplication;

import org.springframework.cloud.stream.annotation.EnableBinding;

import org.springframework.cloud.stream.messaging.Source;

import org.springframework.context.annotation.Bean;

import org.springframework.integration.annotation.InboundChannelAdapter;

import org.springframework.integration.core.MessageSource;

import org.springframework.messaging.support.GenericMessage;

import org.springframework.integration.annotation.Poller;

@EnableBinding(Source.class)

@SpringBootApplication

public class RmqPublishQqApplication {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(RmqPublishQqApplication.class, args);

}

private int counter = 0;

@Bean

@InboundChannelAdapter(value = Source.OUTPUT, poller = @Poller(fixedDelay = "500", maxMessagesPerPoll = "1"))

public MessageSource<String> timerMessageSource() {

return () -> {

counter++;

System.out.println("Spring Cloud Stream message number " + counter);

return new GenericMessage<>("Hello, number " + counter);

};

}

}

The @EnableBinding attribute and reference to the Source class marks this as streaming source, and I used Spring Integration’s InboundChannelAdapter to generate a message, with an incrementing integer, on a pre-defined interval.

My configuration properties are straightforward. I list out all the cluster nodes (to enable failover if a node fails) and provide the name of the existing exchange. I could use Spring Cloud Stream to generate the exchange, but wanted to experiment with creating it ahead of time.

spring.rabbitmq.addresses=localhost:5679,localhost:5680,localhost:5681

spring.rabbitmq.username=guest

spring.rabbitmq.password=guest

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.output.destination=qq-exchange-fanout

spring.cloud.stream.rabbit.bindings.output.producer.exchange-type=fanout

Before starting up the publisher, let’s create the subscriber. Back in start.spring.io, create another app named rmq-subscribe-qq with the same dependencies as before. Click here for a link to download this project definition.

The code for the subscriber is criminally simple. All it takes is the below code to pull a message from the queue and process it.

package com.seroter.demo;

import org.springframework.boot.SpringApplication;

import org.springframework.boot.autoconfigure.SpringBootApplication;

import org.springframework.cloud.stream.annotation.EnableBinding;

import org.springframework.cloud.stream.annotation.StreamListener;

import org.springframework.cloud.stream.messaging.Sink;

@EnableBinding(Sink.class)

@SpringBootApplication

public class RmqSubscribeQqApplication {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(RmqSubscribeQqApplication.class, args);

}

@StreamListener(target = Sink.INPUT)

public void pullMessages(String s) {

System.out.println("Spring Cloud Stream message received: " + s);

}

}

It’s also annotated with an @EnableBinding declaration and references the Sink class which gets this wired up as a message receiver. The @StreamListener annotation marks this method as the one that handles whatever gets pulled off the queue. Note that the new functional paradigm for Spring Cloud Stream negates the need for ANY streaming annotations, but I like the existing model for explaining what’s happening.

The configuration for this project looks pretty similar to the publisher’s configuration. The only difference is that we’re setting the queue name (as “group”) and indicating that Spring Cloud Stream should NOT generate a queue, but use the existing one.

spring.rabbitmq.addresses=localhost:5679,localhost:5680,localhost:5681

spring.rabbitmq.username=guest

spring.rabbitmq.password=guest

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.input.destination=qq-exchange-fanout

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.input.group=qq-1

spring.cloud.stream.rabbit.bindings.input.consumer.queue-name-group-only=true

We’re done! Let’s test it out. I opened up a few console windows, the first pointing to the publisher project, the second to the subscriber project, and a third that will shut down a RabbitMQ node when the time comes.

To start up each Spring Boot project, enter the following command into each console:

./mvnw spring-boot:run

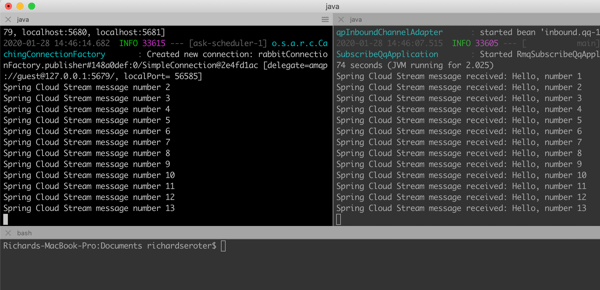

Immediately, I see the publisher publishing, and the subscriber subscribing. The messages arrive in order from a quorum queue.

In the RabbitMQ management console, I can see that we’re processing messages, and that rmq1-qq is the queue leader. Let’s shut down that node. From the other console (not the publisher or subscriber) switch the git folder that you downloaded at the beginning, and enter the following command to remove the RabbitMQ node from the cluster:

docker-compose -f docker/docker-compose-qq-2.yml stop rmq1-qq

As you can see, the node goes away, and there’s no pause in processing, and the Spring Boot app keeps happily sending and receiving data, in order.

Back in the RabbitMQ administration console, note that there’s a new leader for the quorum queue (not rmq1-qq as we originally set up), and just two of the three cluster members are online. All of this “just happens” for you.

For fun, I also started up the stopped node, and watched it quickly rejoin the cluster and start participating in the quorum queue again.

A lot of your systems depend on your messaging middleware. It probably doesn’t get much praise, but everyone sure yells when it goes down! Because distributed systems are hard, keeping that infrastructure highly available with no data loss isn’t easy. I like things like RabbitMQ’s quorum queues, and you should keep playing with them. Check out the terrific documentation to go even deeper.