Yesterday morning, we took the wraps off one of the most interesting Google releases of 2025. The Gemini CLI is here, giving you nearly unlimited access to Gemini from directly within the terminal. This is a new space, but there are other great solutions already out there. Why is this different? Yes, it’s good at multi-step reasoning, code generation, and creative tasks. Build apps, fix code, parse images, build slides, analyze content, or whatever. But what’s truly unique is that It’s fully open source, no cost to use, usable anywhere, and super extensible. Use Gemini 2.5 Pro’s massive context window (1m tokens), multimodality, and strong reasoning ability to do some amazing stuff.

Requirements? Have Node installed, and a Google account. That’s it. You get lots of free queries against our best models. You get more by being a cloud customer if you need it. Let’s have a quick look around, and then I’ll show you four prompts that demonstrate what it can really do.

The slash command shows me what’s available here. I can see and resume previous chats, configure the editor environment, leverage memory via context files like GEMINI.md, change the theme, and use tools. Choosing that option shows us the available tools such as reading files and folders, finding files and folders, performing Google searches, running Shell commands, and more.

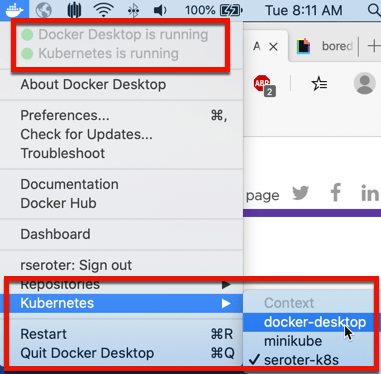

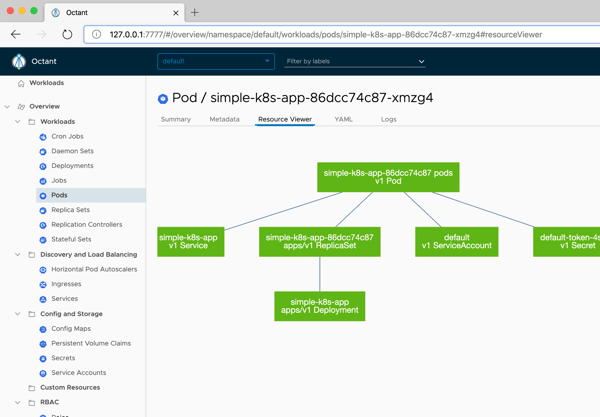

The Gemini CLI has many extensibility points, including use of MCP servers. I added the Cloud Run MCP server but you can add anything here.

I’m only scratching the surface here, so don’t forget to check out the official repo, docs, and blog post announcement. But now, let’s walk through four prompts that you can repeat to experience the power of the Gemini CLI, and why each is a big deal.

Prompt #1 – Do some research.

Software engineering is more than coding. You spend time researching, planning, and thinking. I want to build a new app, but I’m not sure which frontend framework I should use. And I don’t want stale answers from an LLM that was trained a year ago.

I’ve got a new research report on JavaScript frameworks, and also want to factor in web results. My prompt:

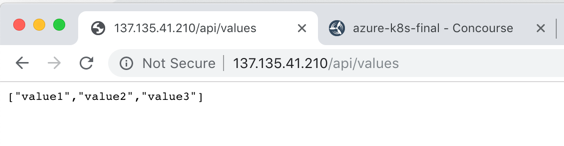

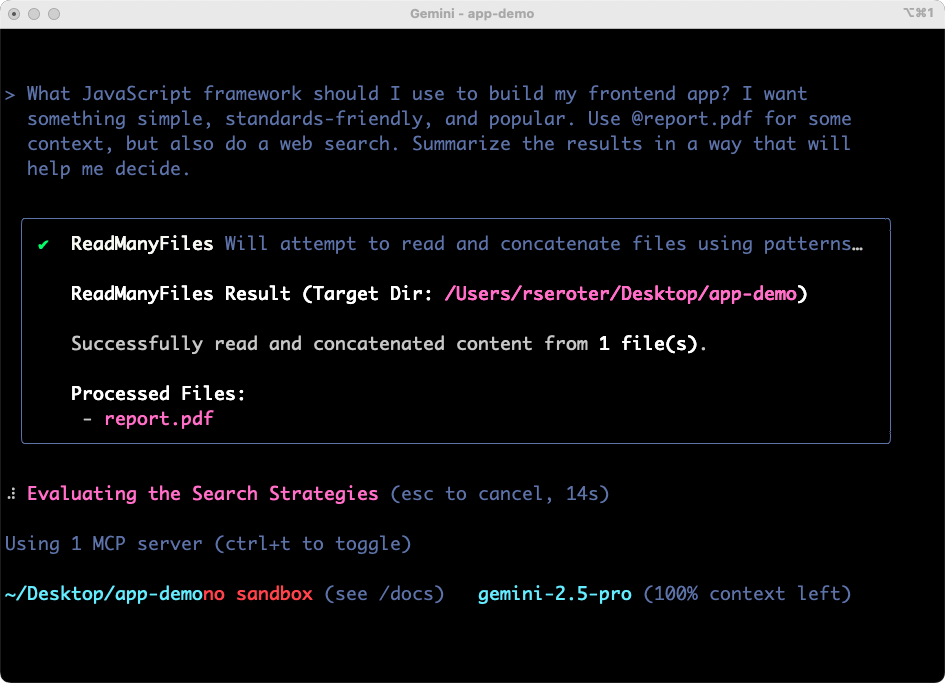

What JavaScript framework should I use to build my frontend app? I want something simple, standards-friendly, and popular. Use @report.pdf for some context, but also do a web search. Summarize the results in a way that will help me decide.

The Gemini CLI figured out some tools to use, successfully considered the file into the prompt, started off on its work searching the web, and preparing results.

The results were solid. I got tradeoff and analysis on three viable options. The summary was helpful and I could have continued going back and forth on clarifying questions. For architects, team leaders, and engineers, having a research partner in the terminal is powerful.

Why was this a big deal? This prompt showed the use of live Google Search, local (binary) file processing, and in-context learning for devs. These tools are changing how I do quick research.

Prompt #2 – Build an app.

These tools will absolutely change how folks build, fix, change, and modernize software. Let’s build something new.

I fed in this prompt, based on my new understanding of relevant JavaScript frameworks.

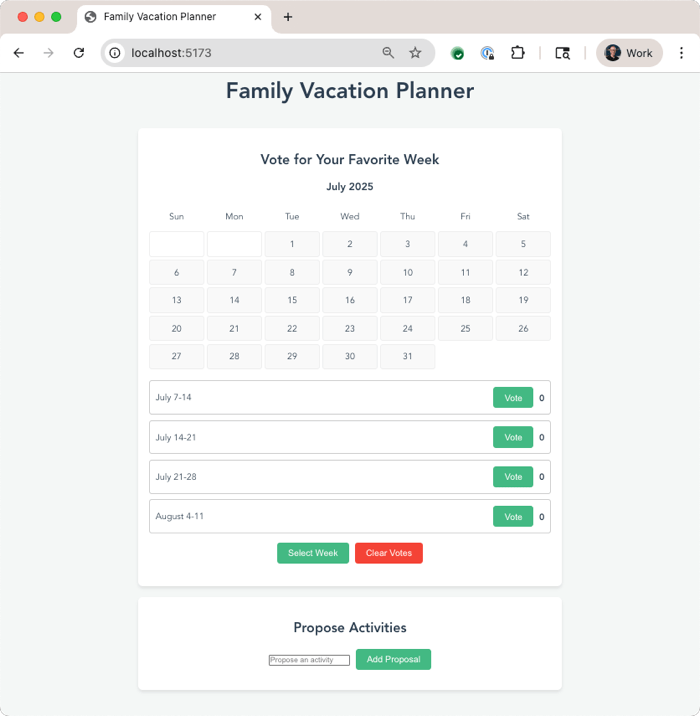

Let’s build a calendar app for my family to plan a vacation together. It should let us vote on weeks that work best, and then nominate activities for each day. Use Vue.js for the JavaScript framework.

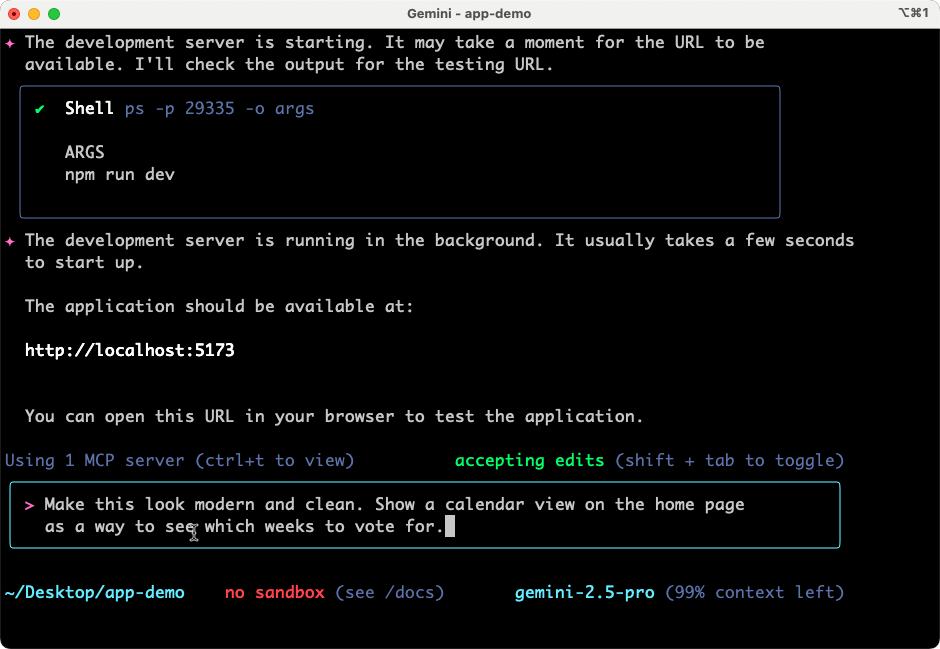

Now to be sure, we didn’t build this to be excellent at one-shot results. Instead, it’s purposely built for an interactive back-and-forth with the software developer. You can start it with –yolo mode to have it automatically proceed without asking permission to do things, and even with –b to run it headless assuming no interactivity. But I want to stay in control here. So I’m not in YOLO mode.

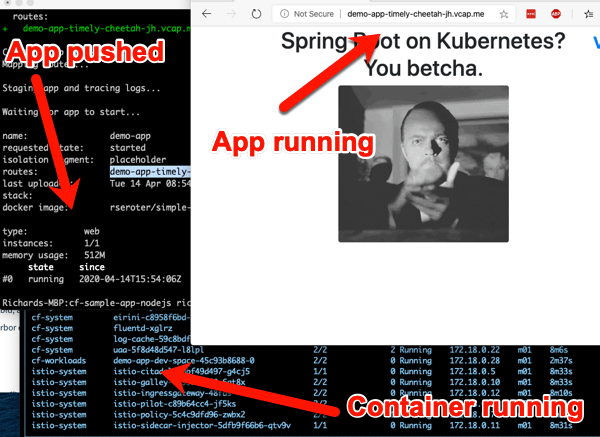

I quickly got back a plan, and was asked if I wanted to proceed.

Gemini CLI also asks me about running Shell commands. I can allow it once, allow it always, or cancel. I like these options. It’s fun watching Gemini make decisions and narrate what it’s working on. Once it’s done building directories, writing code, and evaluating its results, the CLI even starts up a server so that I can test the application. The first draft was functional, but not attractive, so I asked for a cleanup.

The next result was solid, and I could have continued iterating on new features along with look and feel.

Why was this a big deal? This prompt showed iterative code development, important security (request permission) features, and more. We’ll also frequently offer to pop you into the IDE for further coding. This will change how I understand or bootstrap most of the code I work with.

Prompt #3 – Do a quick deploy to the cloud.

I’m terrible at remembering the syntax and flags for various CLI tools. The right git command or Google Cloud CLI request? Just hopeless. The Gemini CLI is my solution. I can ask for what I want, and the Gemini CLI figures out the right type of request to make.

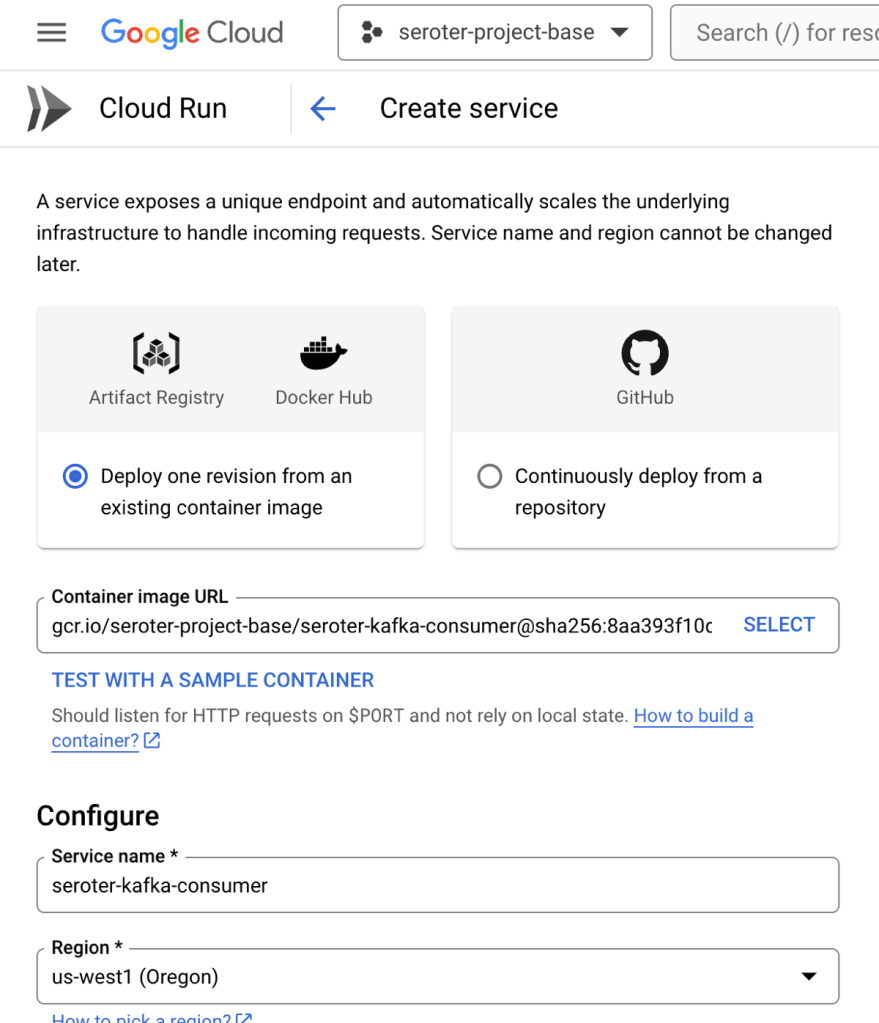

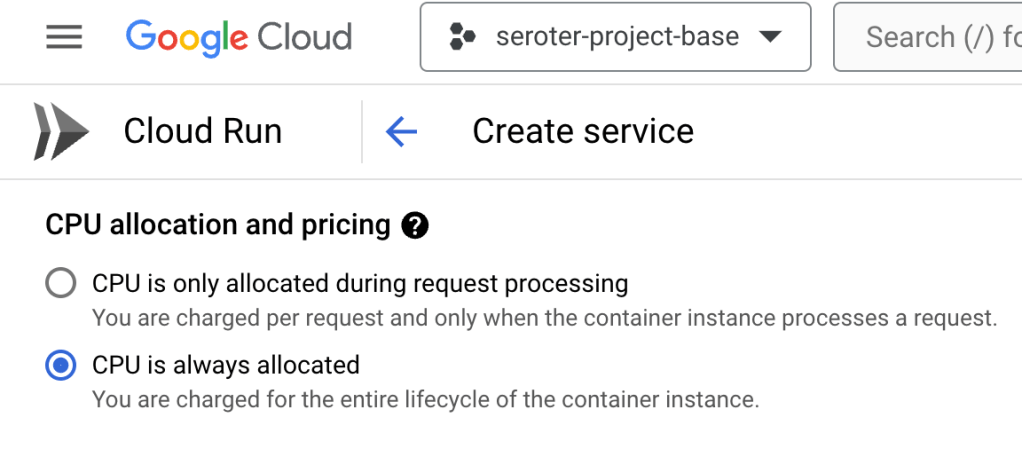

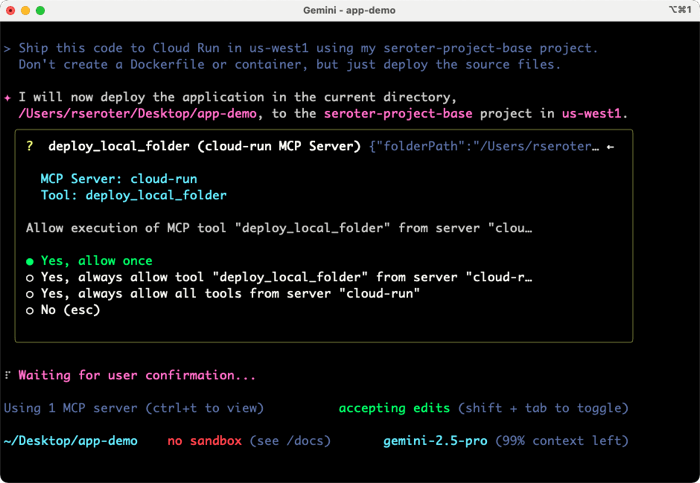

We added MCP as a first-class citizen, so I added the Cloud Run MCP server, as mentioned above. I also made this work without it, as the Gemini CLI figured out the right way to directly call the Google Cloud CLI (gcloud) to deploy my app. But, MCP servers provide more structure and ensure consistent implementation. Here’s the prompt I tried to get this app deployed. Vibe deployment, FTW.

Ship this code to Cloud Run in us-west1 using my seroter-project-base project. Don’t create a Dockerfile or container, but just deploy the source files.

The Gemini CLI immediately recognizes that a known MCP tool can help, and shows me the tool it chose.

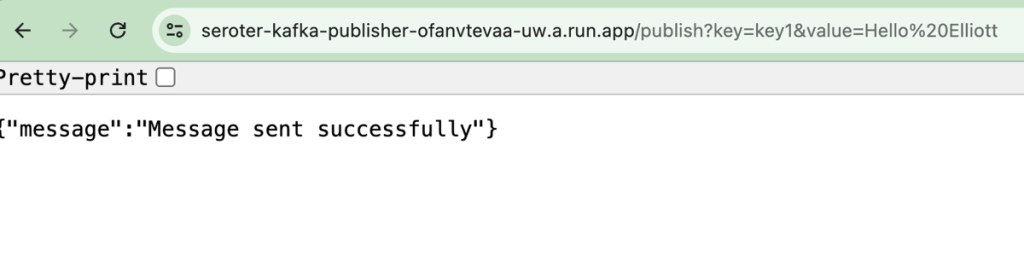

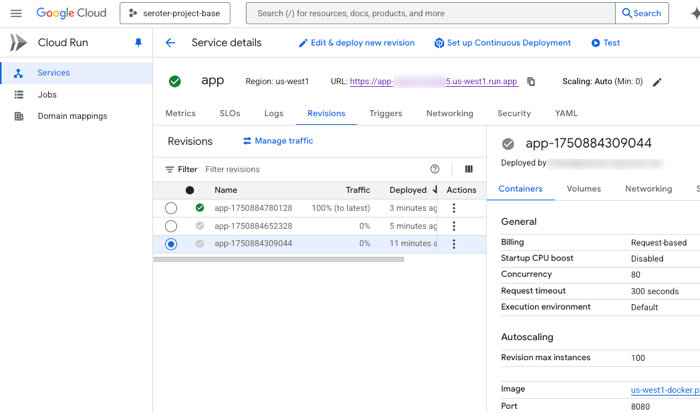

It got going, and shipped my code successfully to Cloud Run using the MCP server. But the app didn’t start correctly. The Gemini CLI noticed that by reading the service logs, and diagnosed the issue. We didn’t provide a reference for which port to listen on. No problem.

It came up with a fix, made the code changes, and redeployed.

Why was this a big deal? We saw the extensibility of MCP servers, and the ability to “forget” some details of exactly how other tools and CLIs work. Plus we observed that the Gemini CLI did some smart reasoning and resolved issues on its own. This is going to change how I deploy, and how much time I spend (waste?) deploying.

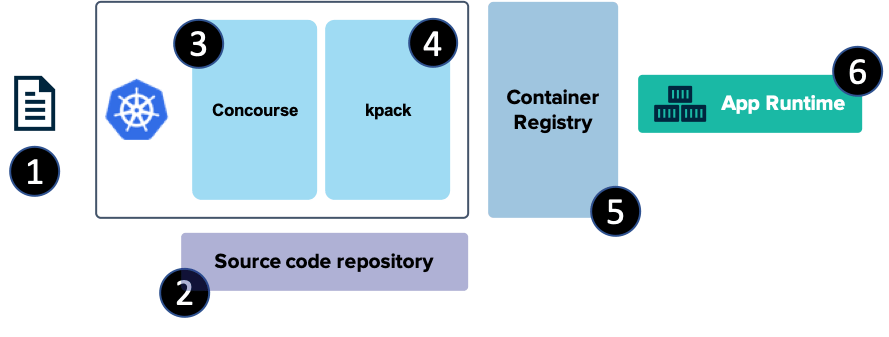

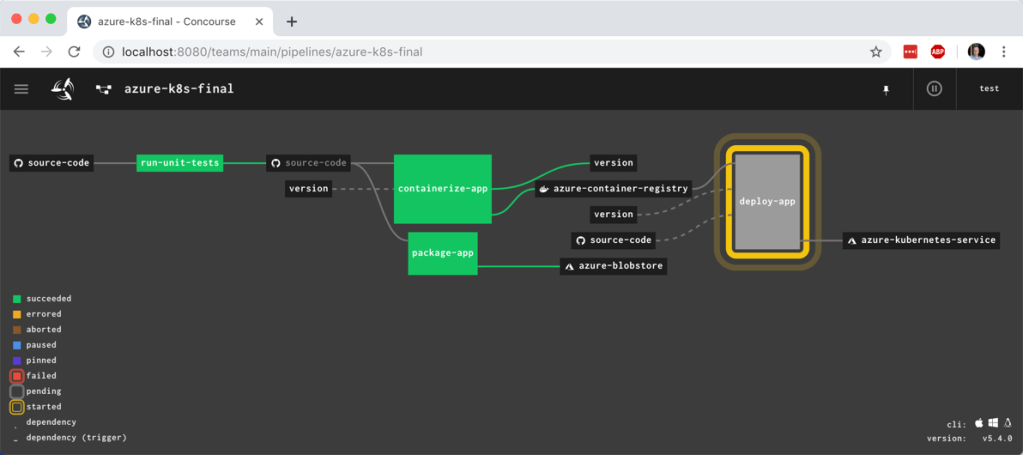

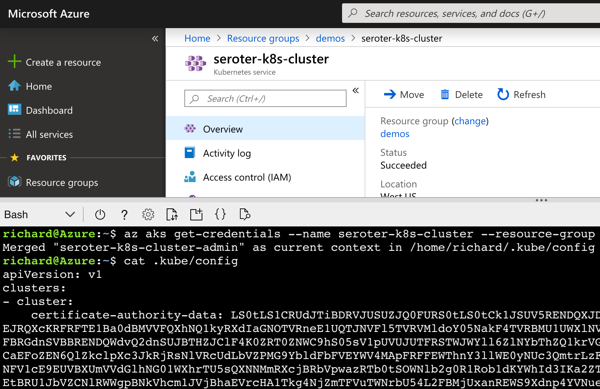

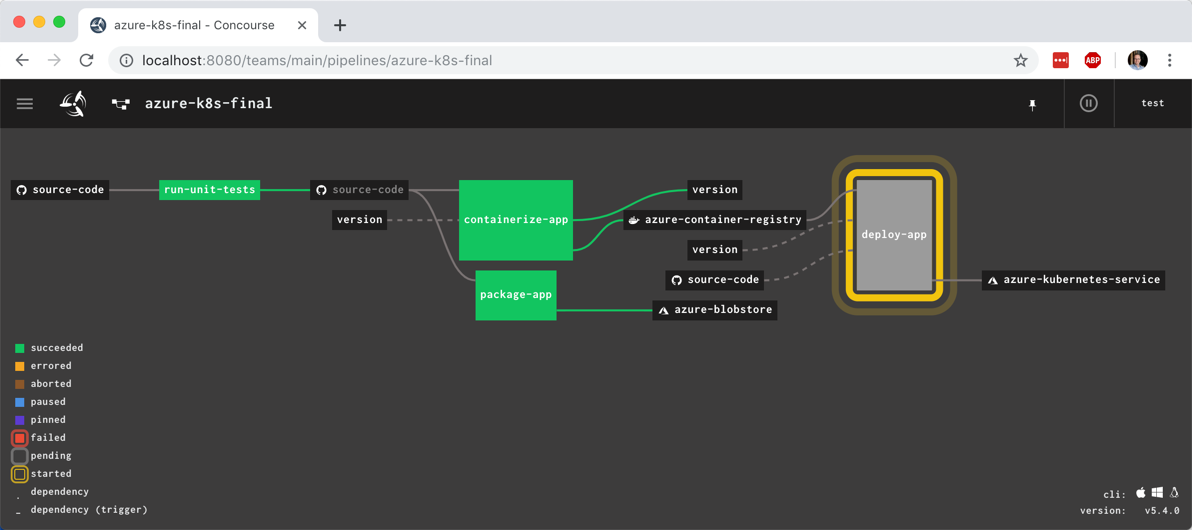

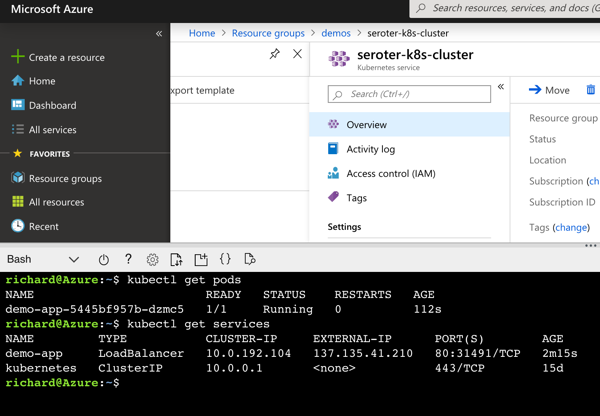

Prompt #4 – Do responsible CI/CD to the cloud.

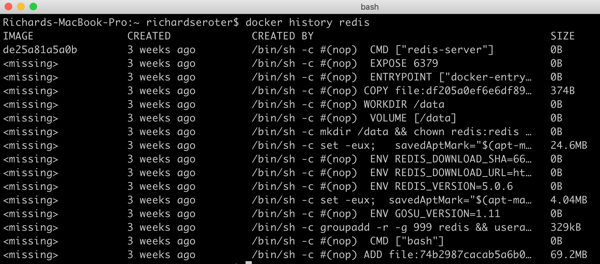

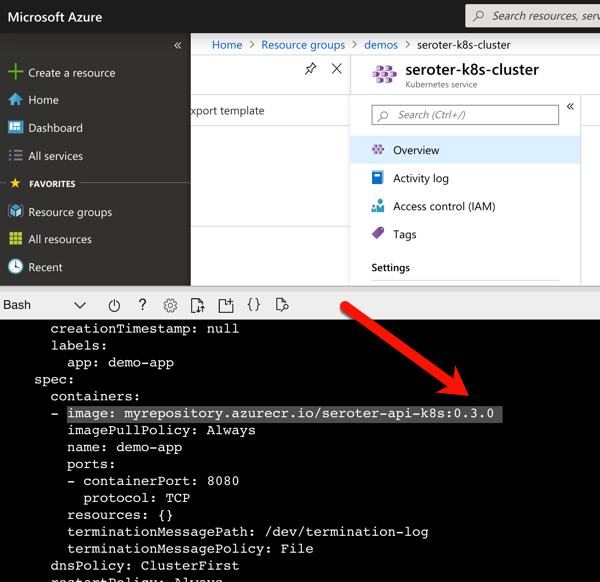

The third prompt was cool and showed how you can quickly deploy to a cloud target, even without knowing the exact syntax to make it happen. I got it working with Kubernetes too. But can the Gemini CLI help me do proper CI/CD, even if I don’t know exactly how to do it? In this case I do know how to set up Google Cloud Build and Cloud Deploy, but let’s pretend I don’t. Here’s the prompt.

Create a Cloud Build file that would build a container out of this app code and store it in Artifact Registry. Then create the necessary Cloud Deploy files that defines a dev and production environment in Cloud Run. Create the Cloud Deploy pipeline, and then reference it in the Cloud Build file so that the deploy happens when a build succeeds. And then go ahead trigger the Cloud Build. Pay very careful attention for how to create the correct files and syntax needed for targeting Cloud Run from Cloud Deploy.

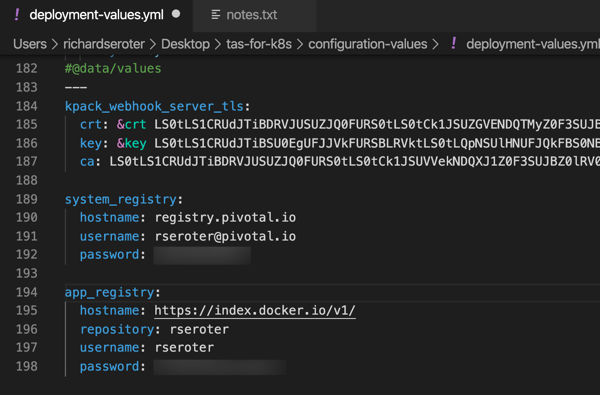

The Gemini CLI started by asking me for some info from my Google Cloud account (project name, target region) and then created YAML files for Cloud Build and Cloud Deploy. It also put together a CLI command to instantiate a Docker repo in Artifact Registry. Now, I know that the setup for Cloud Deploy working with Cloud Run has some specific syntax and formatting. Even with my above command, I can see that I didn’t get syntactically correct YAML in the skaffold file.

I rejected the request of the Gemini CLI to do a deployment, since I knew it would fail. Then I gave it the docs URL for setting up Cloud Run with Cloud Deploy and asked it to make a correction.

That Skaffold file doesn’t look correct. Take a look at the docs (https://cloud.google.com/deploy/docs/deploy-app-run), and follow its guidance for setting up the service YAML files, and referencing the right Skaffold version at the top. Show me the result before pushing a change to the Cloud Deploy pipeline.

Fortunately, the Gemini CLI can do a web fetch and process the latest product documentation. I did a couple of turns and got what I wanted. Then I asked it to go ahead and update the pipeline and trigger Cloud Build.

It failed at first because I didn’t have a Dockerfile, but after realizing that, automatically created one and started the build again.

It took a few iterations of failed builds for the Gemini CLI to land on the right syntax. But it kept dutifully trying, making changes, and redeploy until it got it right. Just like I would have if I were doing it myself!

After that back and forth a few times, I had all the right files, syntax, container artifacts, and pipelines going.

Some of my experiments went faster than others, but that’s the nature of these tools, and I still did this faster overall than I would have manually.

Why was this a big deal? This showcased some sophisticated file creation, iterative improvements, and Gemini CLI’s direct usage of the Google Cloud CLI to package, deploy, and observe running systems in a production-like way. It’ll change how confident I am doing more complex operations.

Background agents, orchestrated agents, conversational AI. All of these will play a part in how we design, build, deploy, and operate software. What does that mean to your team, your systems, and your expectations? We’re about to find out.