A simple use case came to mind yesterday. How would I quickly find out if someone put a too-big file into a repository? In ancient times (let’s say, 2008), here’s what I would have done to solve that. First I’d have to find a file share or FTP location to work with. Then I’d write some custom code with a file system listener that reacted to new documents hitting that file location. After that, I’d look at the size and somehow trigger an alert if the file exceeded some pre-defined threshold. Of course, I’d have to find a server to host this little app on, and figure out how to deploy it. So, solving this might take a month or more. Today? Serverless, baby! I can address this use case in minutes.

I’m learning to program in Go, so ideally, I want a lightweight serverless function written in Go that reacts whenever a new file hits an object store. Is that easy to do in each major public cloud entirely with the console UIs? I just went on a journey to find out, without preparing ahead of time, and am sharing my findings in real time.

Disclaimer: I work at Google Cloud but I am a fairly regular user of other clouds, and was a 12-time Microsoft MVP, mostly focused on Azure. Any mistakes below can be attributed to my well-documented ignorance, and not about me trying to create FUD!

Google Cloud

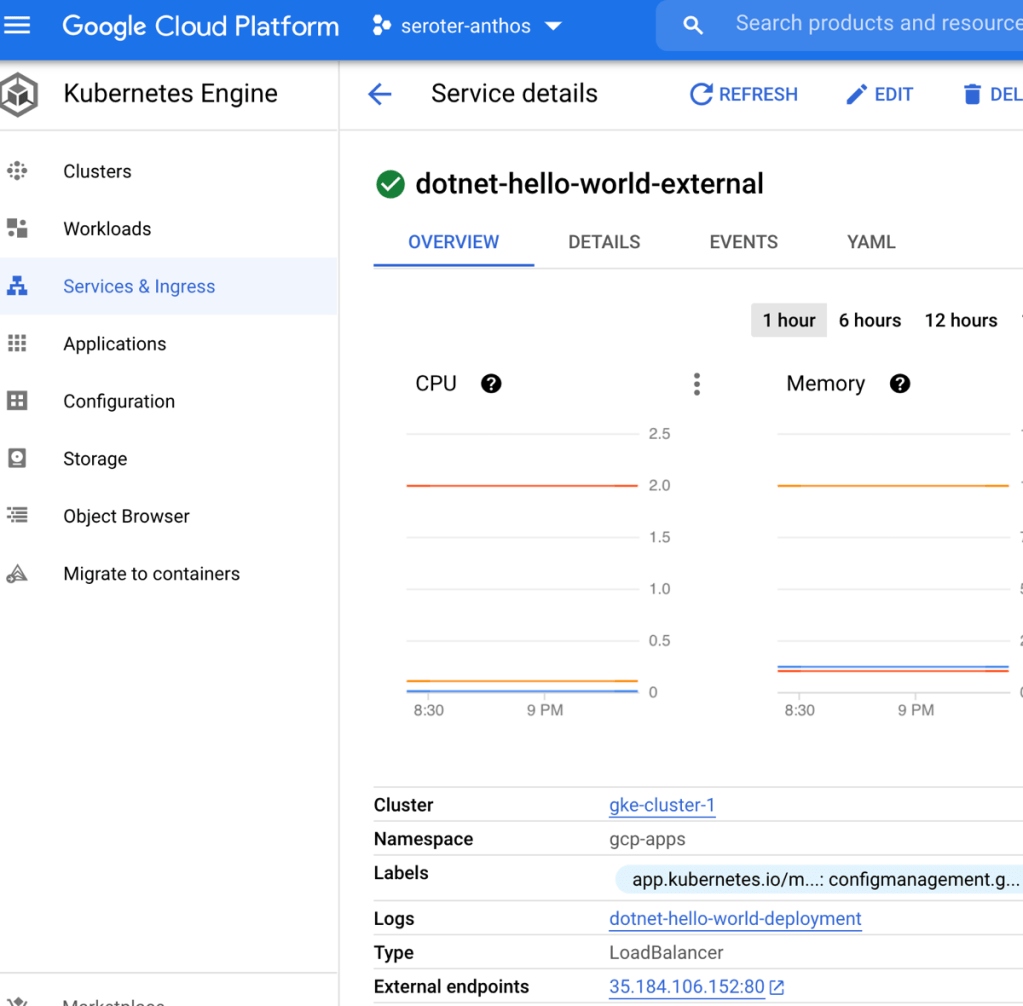

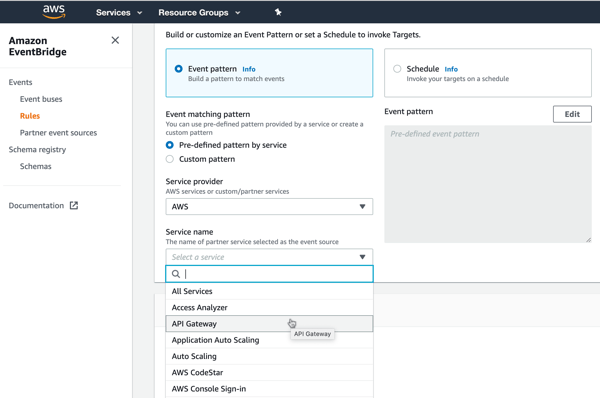

First up, the folks paying my salary. How easily could I add a Cloud Function that responds to things getting uploaded to Cloud Storage?

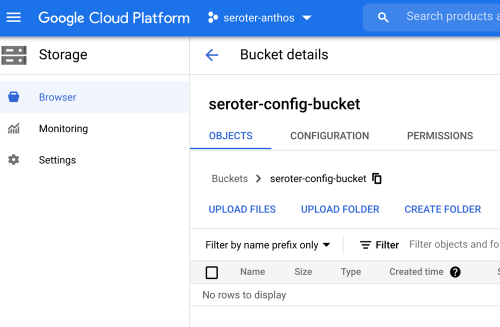

First, I created a new bucket. This takes a few seconds to do.

Hey, what’s this? From the bucket browser, I can actually choose to “process with Cloud Functions.” Let’s see what this does.

Whoa. I get an inline “create function” experience with my bucket-name pre-populated, and the ability to actually author the function code RIGHT HERE.

The Go code template was already populated with a “storage” object as input, and I extended it to include the “size” attribute. Then I added a quick type conversion, and check to see if the detected file was over 1MB.

// Package p contains a Google Cloud Storage Cloud Function.

package p

import (

"context"

"log"

"strconv"

)

// GCSEvent is the payload of a GCS event. Please refer to the docs for

// additional information regarding GCS events.

type GCSEvent struct {

Bucket string `json:"bucket"`

Name string `json:"name"`

Size string `json:"size"`

}

// HelloGCS prints a message when a file is changed in a Cloud Storage bucket.

func HelloGCS(ctx context.Context, e GCSEvent) error {

log.Printf("Processing file: %s", e.Name)

intSize, _ := strconv.Atoi(e.Size)

if intSize > 1000000 {

log.Printf("Big file detected, do something!")

} else {

log.Printf("Normal size file detected")

}

return nil

}

After deploying it, I want to test it. To do so, I just dropped two files—one that was 54 bytes and another that was over 1MB.

Now I’m heading over to the Cloud Functions dashboard and looking at the inline “Logs” tab. This shows me the system logs, as well as anything my function itself emitted. After just a moment, I see the logs my function wrote out, including the “normal size file” and “big file detected” messages.

Goodness that was easy. The same sort of in-experience trigger exists for Pub/Sub, making it easy to generate functions that respond to messaging events.

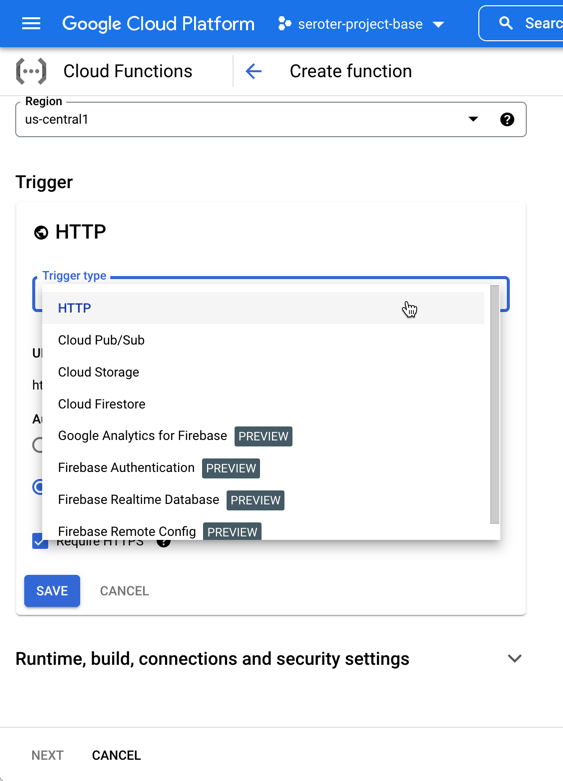

The other UI-driven way to do this. From the Cloud Functions experience, I chose to add a new function. You see here that I have a choice of “trigger.”

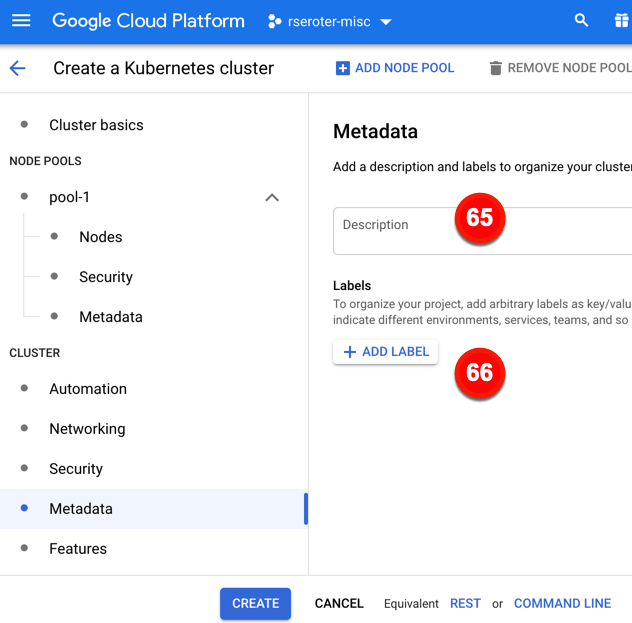

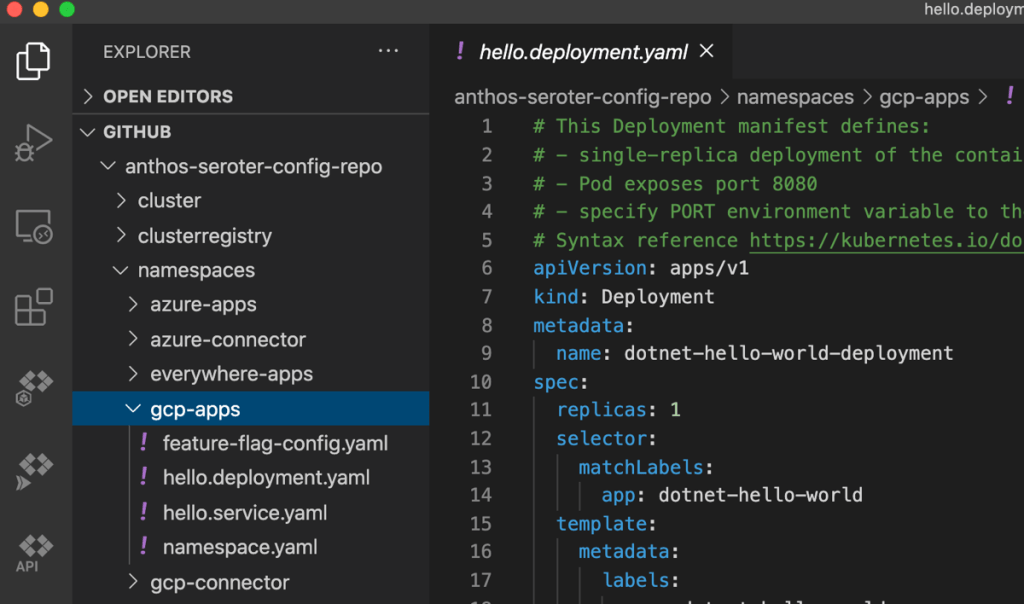

I chose “Cloud Storage” and then picked from a list of possible event types. Let’s also choose the right bucket to listen in on. Note that from this creation wizard, I can also do things like set the memory allocation and timeout period, define the minimum and maximum instance count, add environment variables, reference secrets, and define ingress and egress permissions.

Next, I have to add some source code. I can upload a zip file, reference a zip file in Cloud Storage, point to a source code repository, or add code inline. Let’s do that. What I love is that the code template recognizes my trigger type, and takes in the object representing the storage event. For each language. That’s a big time-saver, and helps new folks understand what the input object should look like. See here:

Here, I picked Go again, used the same code as before, and deployed my function. Once again, it cleanly processes any event related to new files getting added to Cloud Storage. Cloud Functions is underrated, and super easy to work with.

End to end, this solution should take 2-5 minutes tops to complete and deploy. That’s awesome. Past Richard would be crying for joy right now.

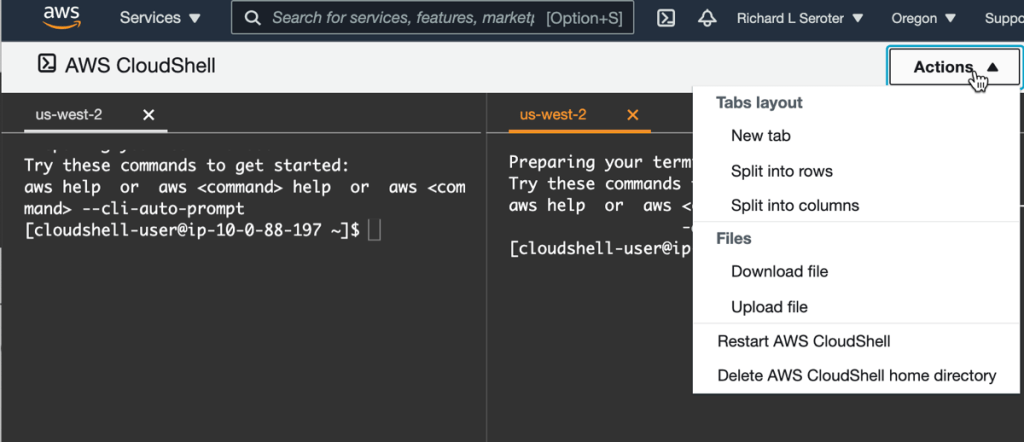

AWS

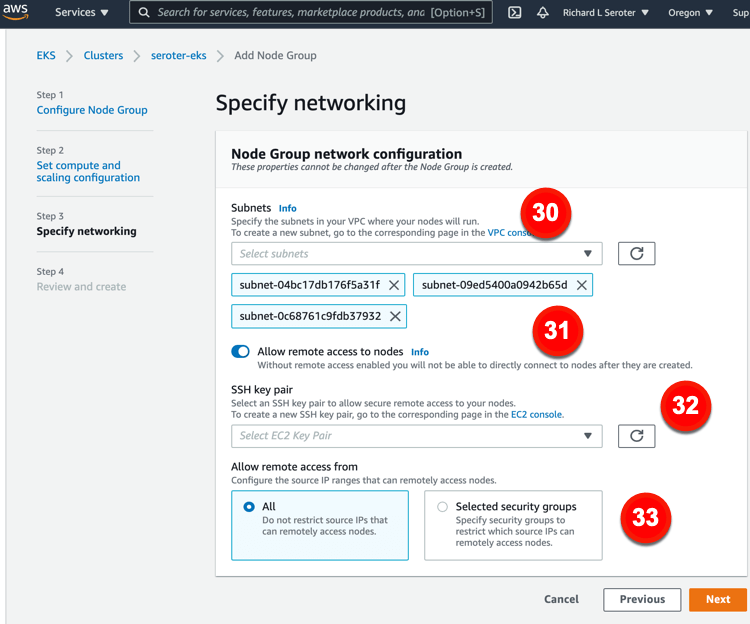

The grandaddy of serverless should be pretty good at this scenario too! From humble beginnings, AWS Lambda has seemingly becomes the preferred app platform in that ecosystem. Let’s use the AWS console experience to build a Lambda function that responds to new files landing in an S3 bucket.

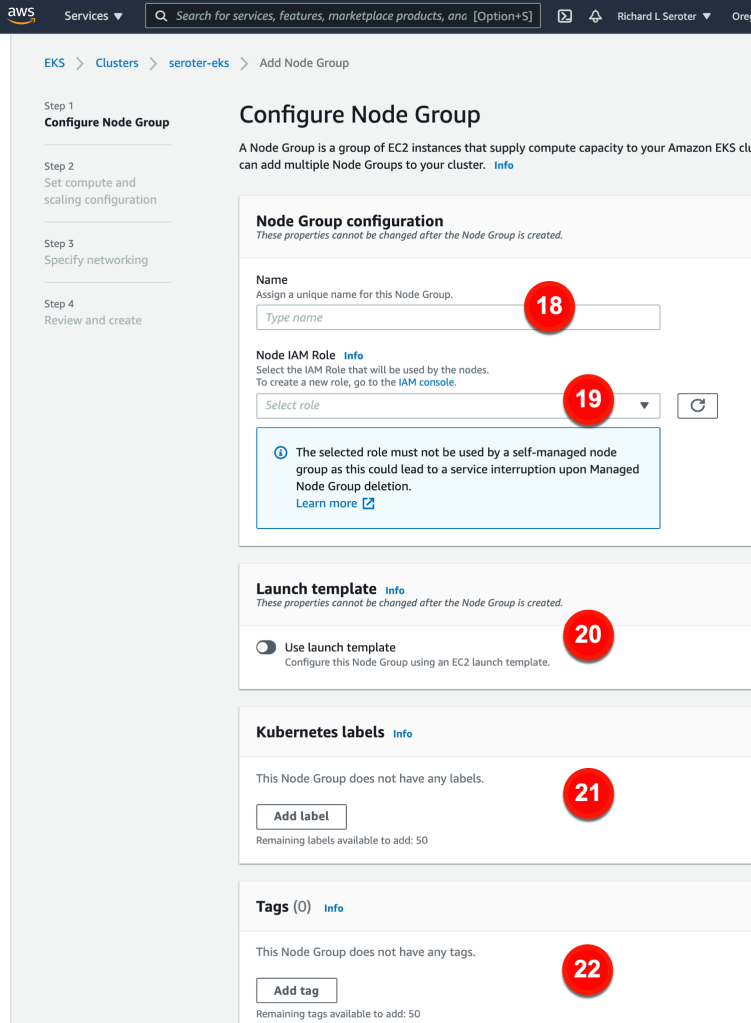

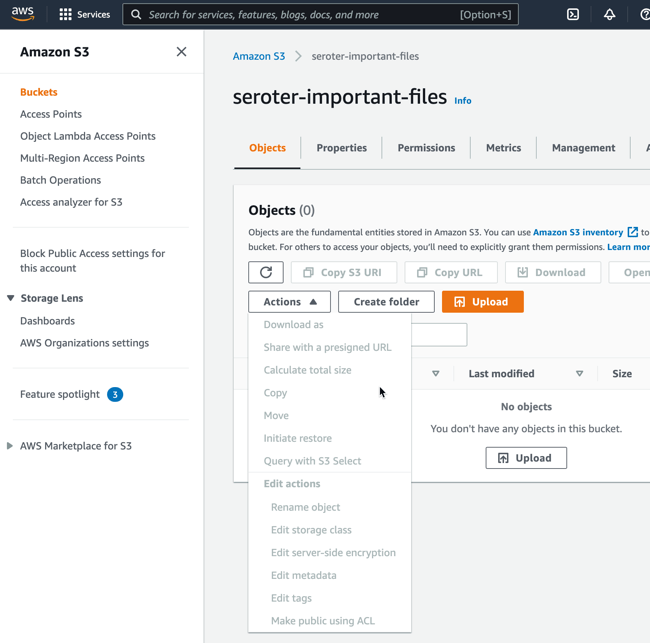

First, I need an S3 bucket. Easy enough, and accepting all the default settings.

My bucket is now there, and I’m looking around, but don’t see any option to create a Lambda function from within this S3 interface. Maybe I’m missing it, but doesn’t seem so.

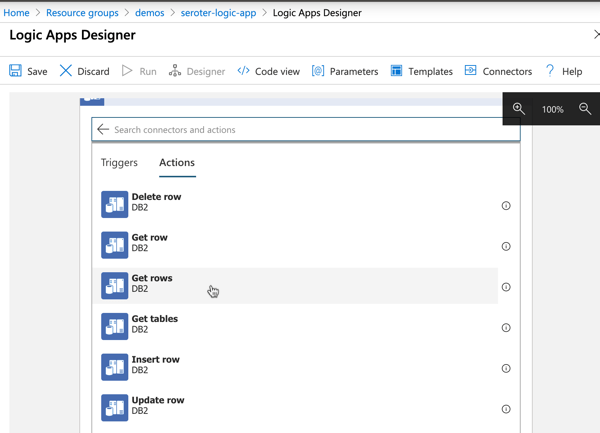

No problem. Off to the Lambda dashboard. I click the very obvious “create function” button and am presented with a screen that asks for my function name and runtime, and the source of code.

Let’s see what “from scratch” means, as I’d probably want some help via a template if it’s too bare bones. I click “create function” to move forward.

Ok, rats, I don’t get an inline code editor if I want to write code in Go. Would have been useful to know beforehand. I’ll delete this function and start over, this time, looking for a blueprint that might provide a Go template for reading from S3.

Doesn’t look like there’s anything for Go. If I want a blueprint, I’m choosing between Python and Node. Ok, I’ll drop by Go requirement, and crank out this Lambda function in JavaScript. I picked that s3-get-object template, and then provide a function name and a role that can access S3. I’m asked for details about my S3 trigger (bucket name, event type) and shown the (uneditable) blueprint code. I’d like to make changes, but I guess I wait until later, so I create the function.

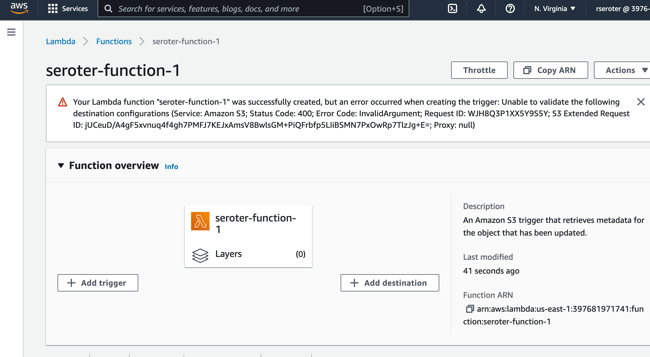

Shoot, I did something wrong. Got an error that, on the plus side, is completely opaque and unreadable.

Not be stopped, I’ll try clicking “add trigger” here, which lets me choose among a variety of sources, including S3, and this configuration seems to work fine.

I want to update the source code of my function, so that it logs alerts for big files. I updated the Lambda code (after looking up the structure of the inbound event object) and clicked “deploy” to apply this new code.

Not too bad. Ok, let’s test this. In S3, I just dropped a handful of files into the bucket. Back in the Lambda console, I jump to the “Monitor” tab to see what’s up.

I’ve got the invocations listed here. I can’t see the logs directly, but looks like I need to click the LogStream links to view the invocation logs. Doing that takes me to a new window where I’m now in CloudWatch. I now see the logs for this particular set of invocations.

Solid experience. A few hiccups, but we’ll chalk some of that up to my incompetence, and the remainder to the fact that AWS UIs aren’t always the most intuitive.

Microsoft Azure

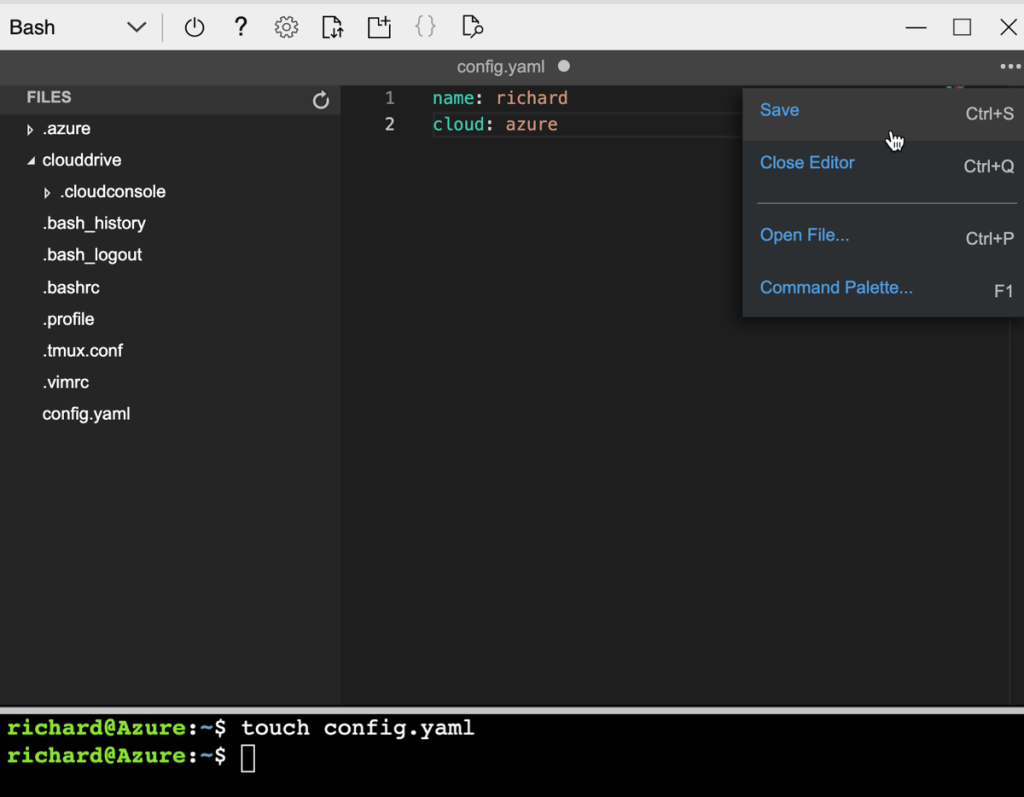

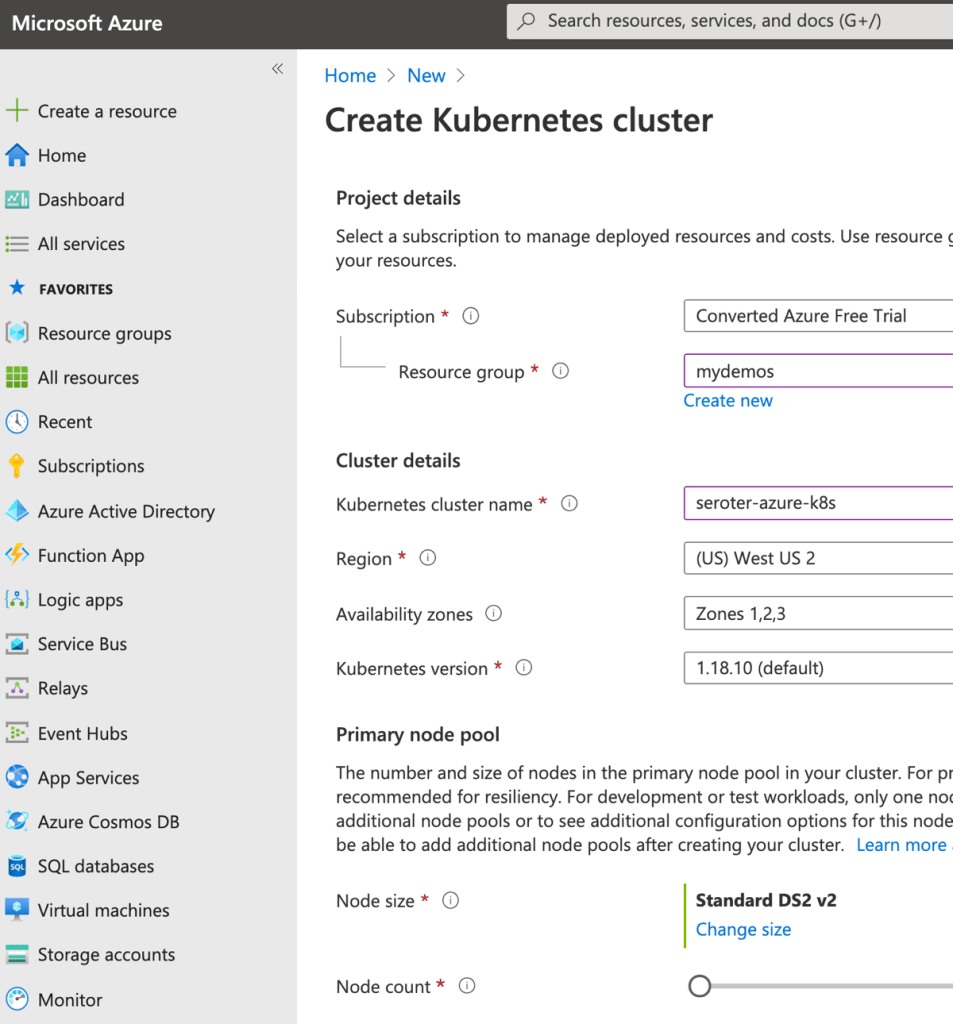

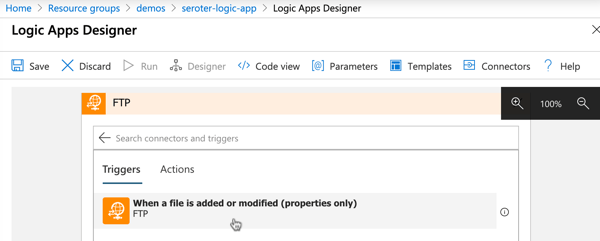

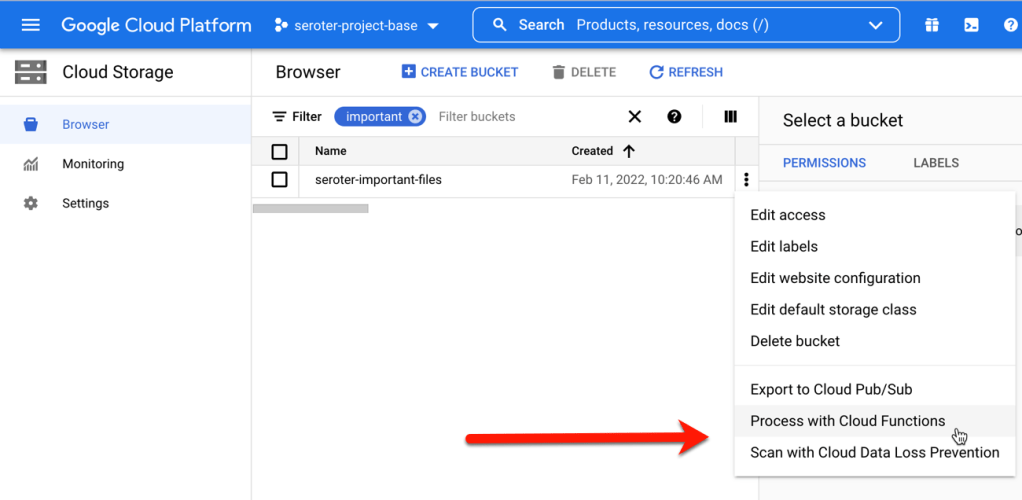

Azure, my old friend. Let’s see how I can use the Azure Portal to trigger an Azure Function whenever I add something to a storage bucket. Here we go.

Like with the walkthroughs above, I also need to setup some storage. From the home page, I click “create resource” and navigate on the left-hand side to “Storage.” And … don’t see Azure Storage. *Expletive*.

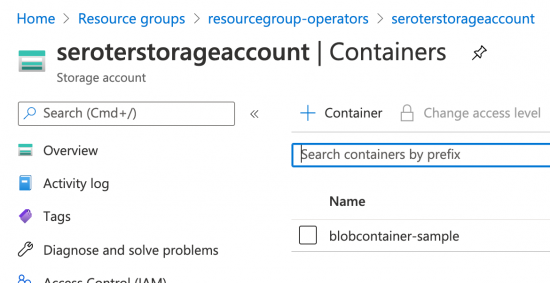

I can’t find what category it’s in, but just noticed it in the “Get started” section. It’s weird, but whatever. I pick an Azure subscription and resource group, try to set a name (and remember that it doesn’t accept anything but letters and numbers, no dashes), and proceed. It validates something (not sure I’ve ever seen this NOT pass) and then I can click “create.”

After thirty seconds, I have my storage account. Azure loves “things contained within things” so this storage account itself doesn’t hold objects. I create a “container” to hold my actual documents.

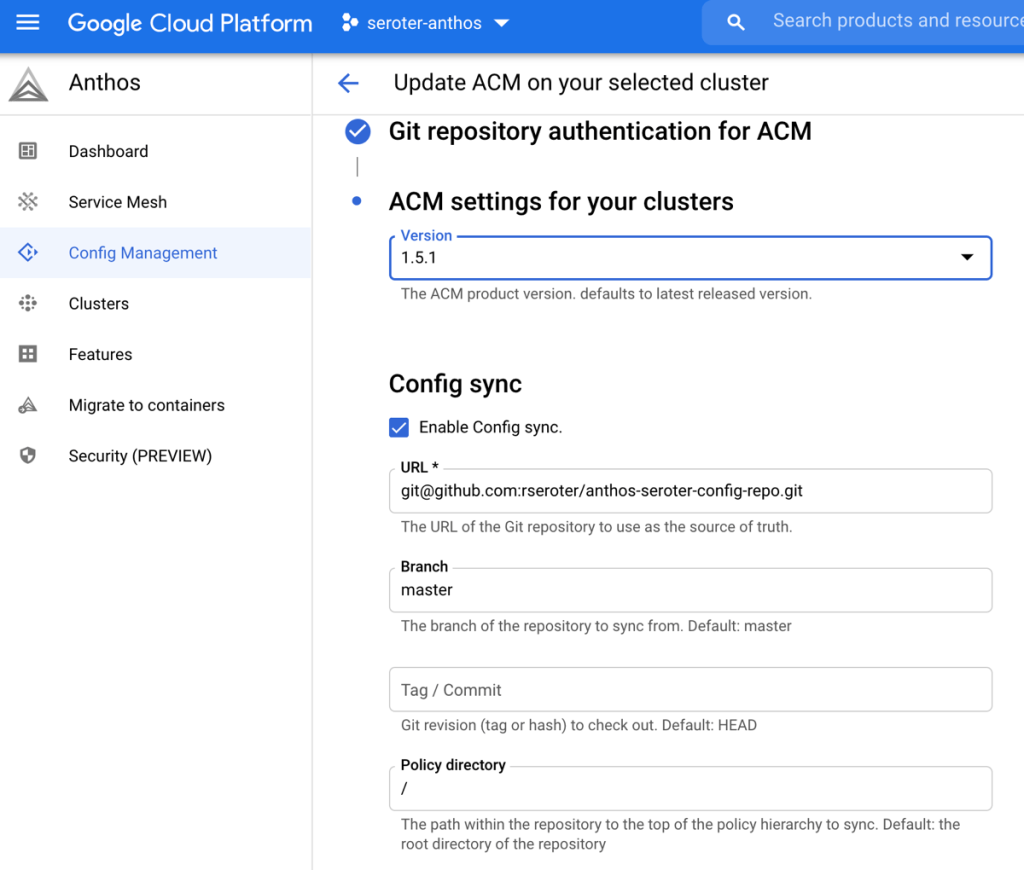

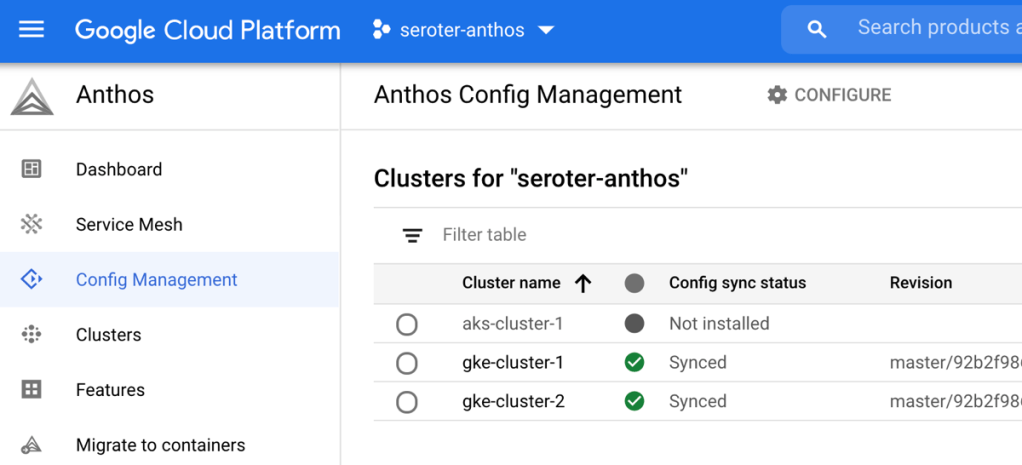

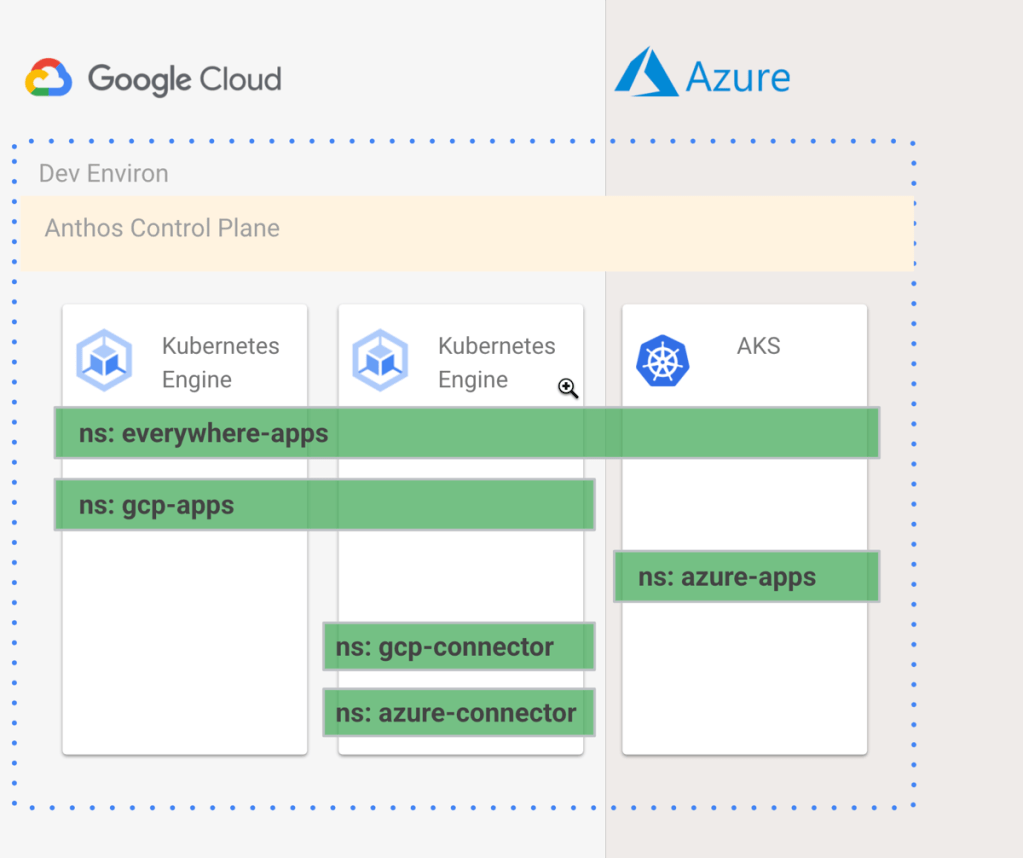

Like with Lambda, I don’t see a way from this service to create an event-driven function. [Updated 2-13-22: A reader pointed out that there is an “events” experience in Storage that lets you somewhat create a function (but not the Function App itself). While convenient, the wizard doesn’t recognize where you are, and asks what sort of Function (storage!) you want to build. But it’s definitely something.]

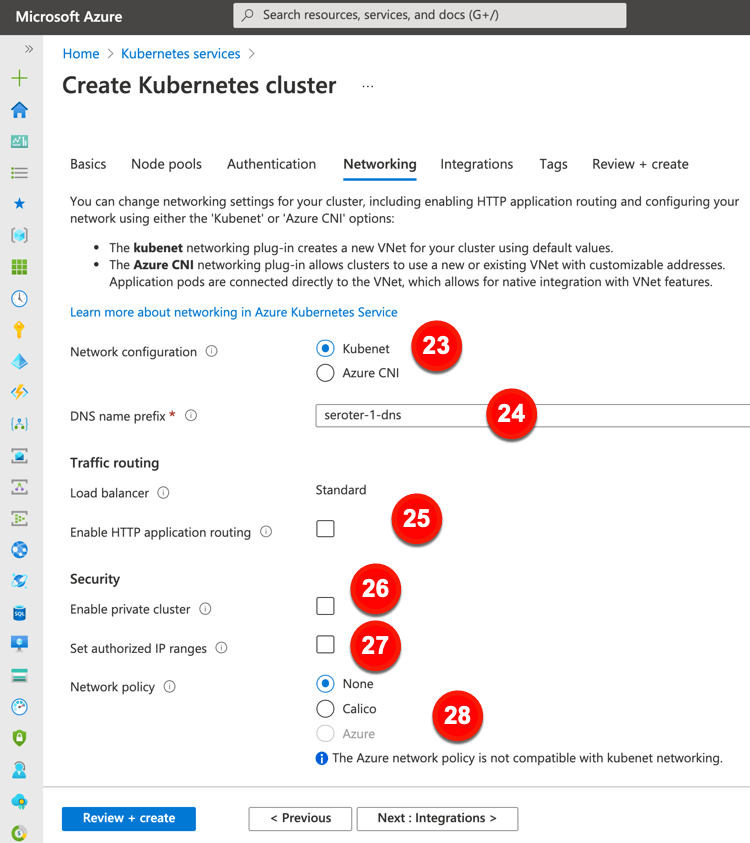

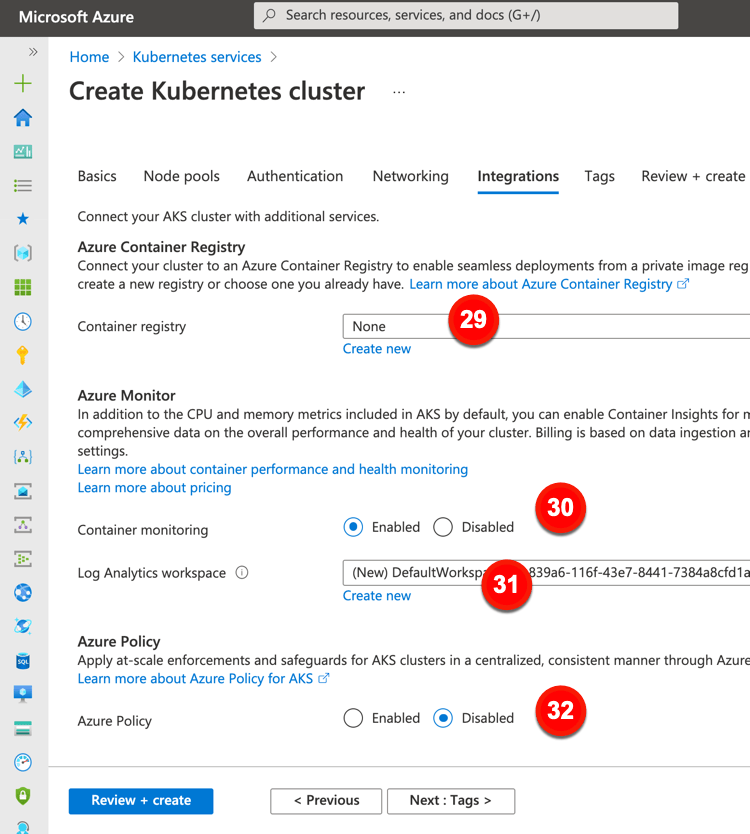

So, let’s go to the Azure Functions experience. I’m asked to create a “Function App.” There’s no option to choose Go as a managed language, so I’ll once again pick Node. YOU WIN AGAIN JAVASCRIPT.

I move on to the next pane of the wizard where I’m asked about hosting stack. Since this is 2022, I chose Linux, even though Windows is somehow the recommended stack for Node functions. After a few moments, I have my Function app.

As with the storage scenario, this Function app isn’t actually the function. I need to add a function to the app. Ok, no problem. Wait, apparently you can’t use the inline editor for Linux-based functions because of reasons.

Sigh. I’ll create a new Function App, this time choosing Windows as the host. Now when I choose to add a function to this Function App, I see the option for “develop in portal”, and can choose a trigger. That’s good. I’ll choose the Storage Blob trigger, but I’m not clear on the parameter values I’m supposed to provide. Hmm, the “learn more” goes to a broken page. Found it by Googling directly. Looks like the “path” is the name of the container in the account, and {name} is a standard token.

The creation succeeded, and now I have a function. Sweet. Let’s throw some code in here. The “Code + Test” window looks like an inline editor. I updated the code to do a quick check of file size, and hope it works.

After saving it (I don’t see a concept of versioning), I can test it out. Like I did for Google Cloud and AWS, I dragged a couple of files onto the browser window pointing at the Storage Blob. Looks like the Azure Portal doesn’t support drag-and-drop. I’ll use the “upload files” wizard like an animal. After uploading, I switch back to the Azure Functions view which offers a “Monitor” view.

I don’t love that “results may be delayed for up to 5 minutes” as I’m really into instant gratification. The Function dashboard shows two executions right away, but the logs are still delayed for minutes after that. Eventually I see the invocations show up, and it shows execution history (not app logs).

I can’t seem to find the application logs, as the “logs” tab here seems to show a stream, but nothing appears here for me. Application Insights doesn’t seem to show the logs either. They could be lost to the universe, or more likely, I’m too bad at this to find them.

Regardless, it works! My Azure Function runs when objects land in my Storage account.

Wrap Up

As to the options considered here, it seemed obvious to me that Google Cloud has the best dev experience. The process of creating a function is simple (and even embedded in related services), the inline editor easily works for all languages, and the integrated log monitoring made my build-deploy-test loop faster. The AWS experience was fine overall, although inconsistent depending on your programming language. And the Azure experience, honestly, felt super clunky and the Windows-centricity feels dated. I’m sure they’ll catch up soon.

Overall, this was pretty fun. Managed services and serverless computing makes these quick solutions so simple to address. It’s such an improvement for how we had to do this before!