I feel silly admitting that I barely understand what happens in the climactic scene of the 80s movie Trading Places. It has something to do with short-selling commodities—in this case, concentrated orange juice. Let’s talk about commodities, which Investopedia defines as:

a basic good used in commerce that is interchangeable with other goods of the same type. Commodities are most often used as inputs in the production of other goods or services. The quality of a given commodity may differ slightly, but it is essentially uniform across producers.

Our industry has rushed to declare Kubernetes a commodity, but is it? It is now a basic good used as input to other goods and services. But is uniform across producers? It seems to me that the Kubernetes API is commoditized and consistent, but the platform experience isn’t. Your Kubernetes experience isn’t uniform across Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE), AWS Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS), Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS), VMware PKS, Red Hat OpenShift, Minikube, and 130+ other options. No, there are real distinctions that can impact your team’s chance of success adopting it. As you’re choosing a Kubernetes product to use, pay upfront attention to provisioning, upgrades, scaling/repair, ingress, software deployment, and logging/monitoring.

I work for Google Cloud, so obviously I’ll have some biases. That said, I’ve used AWS for over a decade, was an Azure MVP for years, and can be mostly fair when comparing products and services.

1. Provisioning

Kubernetes is a complex distributed system with lots of moving parts. Multi-cluster has won out as a deployment strategy (versus one giant mega cluster segmented by namespace), which means you’ll provision Kubernetes clusters with some regularity.

What do you have to do? How long does it take? What options are available? Those answers matter!

Kubernetes offerings don’t have identical answers to these questions:

- Do you want clusters in a specific geography?

- Should clusters get deployed in an HA fashion across zones?

- Can you build a tiny cluster (small machine, single node) and a giant cluster?

- Can you specify the redundancy of the master nodes? Is there redundancy?

- Do you need to choose a specific Kubernetes version?

- Are worker nodes provisioned during cluster build, or do you build separately and attach to the cluster?

- Will you want persistent storage for workloads?

- Are there “special” computing needs, including large CPU/memory nodes, GPUs, or TPUs?

- Are you running Windows containers in the cluster?

As you can imagine, since GKE is the original managed Kubernetes, there’s lots of options for you when building clusters. Or, you can do a one-click install of a “starter” cluster, which is pretty great.

2. Upgrades

You got a cluster running? Cool! Day 2 is usually where the real action’s at. Let’s talk about upgrades, which are a fact of life for clusters. What gets upgraded? Namely the version of Kubernetes, and the configuration/OS of the nodes themselves. The level of cluster management amongst the various providers is not uniform.

GKE supports automated upgrades of everything in the cluster, or you can trigger it manually. Either way, you don’t do any of the upgrade work yourself. Release channels are pretty cool, too. DigitalOcean looks somewhat similar to GKE, from an upgrade perspective. AKS offers manually triggered upgrades. AWS offers kinda automated or extremely manual (i.e. creating new node groups or using Cloud Formation), depending on whether you used managed or unmanaged worker nodes.

3. Scaling / Repairs

Given how many containers you can run on a good-sized cluster, you may not have to scale your cluster TOO often. But, you may also decide to act in a “cloudy” way, and purposely start small and scale up as needed.

Like with most any infrastructure platform, you’ll expect to scale Kubernetes environments (minus local dev environments) both vertically and horizontally. Minimally, demand that your Kubernetes provider can scale clusters via manual commands. Increasingly, auto-scaling of the cluster is table-stakes. And don’t forget scaling of the pods (workloads) themselves. You won’t find it everywhere, but GKE does support horizontal pod autoscaling and vertical pod autoscaling too.

Also, consider how your Kubernetes platform handles the act of scaling. It’s not just about scaling the nodes or pods. It’s how well the entire system swells to absorb the increasing demand. For instance, Bayer Crop Science worked with Google Cloud to run a 15,000 node cluster in GKE. For that to work, the control planes, load balancers, logging infrastructure, storage, and much more had to “just work.” Understand those points in your on-premises or cloud environment that will feel the strain.

Finally, figure out what you want to happen when something goes wrong with the cluster. Does the system detect a down worker and repair/replace it? Most Kubernetes offerings support this pretty well, but do dig into it!

4. Ingress

I’m not a networking person. I get the gist, and can do stuff, but I quickly fall into the pit of despair. Kubernetes networking is powerful, but not simple. How do containers, pods, and clusters interact? What about user traffic in and out of the cluster? We could talk about service meshes and all that fun, but let’s zero in on ingress. Ingress is about exposing “HTTP and HTTPS routes from outside the cluster to services within the cluster.” Basically, it’s a Layer 7 front door for your Kubernetes services.

If you’re using Kubernetes on-premises, you’ll have some sort of load balancer configuration setup available, maybe even to use with an ingress controller. Hopefully! In the public cloud, major providers offer up their load-balancer-as-a-service whenever you expose a service of type “LoadBalancer.” But, you get a distinct load balancer and IP for each service. When you use an ingress controller, you get a single route into the cluster (still load balanced, most likely) and the traffic is routed to the correct pod from there. Microsoft, Amazon, and Google all document their way to use ingress controllers with their managed Kubernetes.

Make sure you investigate the network integrations and automation that comes with your Kubernetes product. There are super basic configurations (that you’ll often find in local dev tools) all the way to support for Istio meshes and ingress controllers.

5. Software Deployment

How do you get software into your Kubernetes environment? This is where the commoditization of the Kubernetes API comes in handy! Many software products know how to deploy containers to a Kubernetes environment.

Two areas come to mind here. First, deploying packaged software. You can use Helm to deploy software to most any Kubernetes environment. But let’s talk about marketplaces. Some self-managed software products deliver some form of a marketplace, and a few public clouds do. AWS has the AWS Marketplace for Containers. DigitalOcean has a nice little marketplace for Kubernetes apps. In the Google Cloud Marketplace, you can filter by Kubernetes apps, and see what you can deploy on GKE, or in Anthos environments. I didn’t notice a way in the Azure marketplace to find or deploy Kubernetes-targeted software.

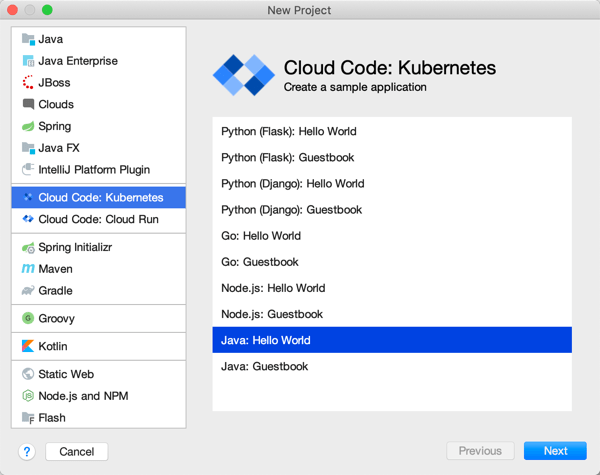

The second area of software deployment I think about relates to CI/CD systems for custom apps. Here, you have a choice of 3rd party best-of-breed tools, or whatever your Kubernetes provider bakes in. AWS CodePipeline or CodeDeploy can deploy apps to ECS (not EKS, it seems). Azure Pipelines looks like it deploys apps directly to AKS. Google Cloud Build makes it easy to deploy apps to GKE, App Engine, Functions, and more.

When thinking about software deployment, you could also consider the app platforms that run atop a Kubernetes foundation, like Knative and in the future, Cloud Foundry. These technologies can shield you from some of the deployment and configuration muck that’s required to build a container, deploy it, and wire it up for routing.

6. Logging/Monitoring

Finally, take a look at what you need from a logging and monitoring perspective. Most any Kubernetes system will deliver some basic metrics about resource consumption—think CPU, memory, disk usage—and maybe some Kubernetes-specific metrics. From what I can tell, the big 3 public clouds integrate their Kubernetes services with their managed monitoring solutions. For example, you get visibility into all sorts of GKE metrics when clusters are configured to use Cloud Operations.

Then there’s the question of logging. Do you need a lot of logs, or is it ok if logs rotate often? DigitalOcean rotates logs when they reach 10MB in size. What kind of logs get stored? Can you analyze logs from many clusters? As always, not every Kubernetes behaves the same!

Plenty of other factors may come into play—things like pricing model, tenancy structure, 3rd party software integration, troubleshooting tools, and support community come to mind—when choosing a Kubernetes product to use, so don’t get lulled into a false sense of commoditization!