API access is quickly becoming the most important aspect of any cloud platform. How easily can you automate activities using programmatic interfaces? What hooks do you have to connect on-premises apps to cloud environments? So far in this long-running blog series, I’ve taken a look at how to provision, scale, and manage the cloud environments of five leading cloud providers. In this post, I’ll explore the virtual-machine-based API offerings of the same providers. Specifically, I’m assessing:

- Login mechanism. How do you access the API? Is it easy for developers to quickly authenticate and start calling operations?

- Request and response shape. Does the API use SOAP or REST? Are payloads XML, JSON, or both? Does a result set provide links to follow to additional resources?

- Breadth of services. How comprehensive is the API? Does it include most of the capabilities of the overall cloud platform?

- SDKs, tools, and documentation. What developer SDKs are available, and is there ample documentation for developers to leverage?

- Unique attributes. What stands out about the API? Does it have any special capabilities or characteristics that make it stand apart?

As an aside, there’s no “standard cloud API.” Each vendor has unique things they offer, and there’s no base interface that everyone conforms to. While that makes it more challenge to port configurations from one provider to the next, it highlights the value of using configuration management tools (and to a lesser extent, SDKs) to provide abstraction over a cloud endpoint.

Let’s get moving, in alphabetical order.

DISCLAIMER: I’m the VP of Product for CenturyLink’s cloud platform. Obviously my perspective is colored by that. However, I’ve taught four well-received courses on AWS, use Microsoft Azure often as part of my Microsoft MVP status, and spend my day studying the cloud market and playing with cloud technology. While I’m not unbiased, I’m also realistic and can recognize strengths and weaknesses of many vendors in the space.

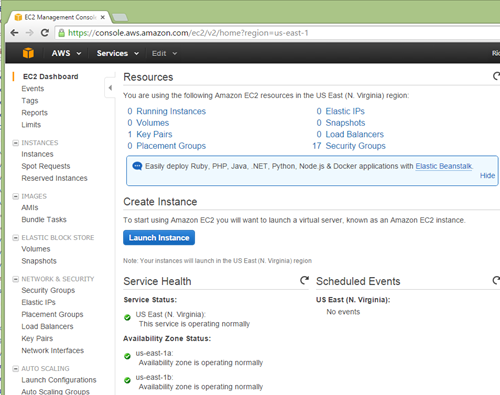

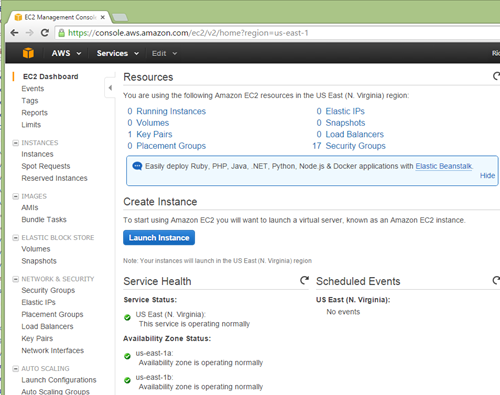

Amazon EC2 is among the original cloud infrastructure providers, and has a mature API.

Login mechanism

For AWS, you don’t really “log in.” Every API request includes an HTTP header made up of the hashed request parameters signed with your private key. This signature is verified by AWS before executing the requested operation.

A valid request to the API endpoint might look like this (notice the Authorization header):

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=UTF-8

X-Amz-Date: 20150501T130210Z

Host: ec2.amazonaws.com

Authorization: AWS4-HMAC-SHA256 Credential=KEY/20150501/us-east-1/ec2/aws4_request, SignedHeaders=content-type;host;x-amz-date, Signature=ced6826de92d2bdeed8f846f0bf508e8559e98e4b0194b84example54174deb456c

[request payload]

Request and response shape

Amazon still supports a deprecated SOAP endpoint, but steers everyone to it’s HTTP services. To be clear, it’s not REST; while the API does use GET and POST, it typically throws a command and all the parameters into the URL. For instance, to retrieve a list of instances in your account, you’d issue a request to:

https://ec2.amazonaws.com/?Action=DescribeInstances&AUTHPARAMS

For cases where lots of parameters are required – for instance, to create a new EC2 instance – all the parameters are signed in the Authorization header and added to the URL.

https://ec2.amazonaws.com/?Action=RunInstances

&ImageId=ami-60a54009

&MaxCount=3

&MinCount=1

&KeyName=my-key-pair

&Placement.AvailabilityZone=us-east-1d

&AUTHPARAMS

Amazon APIs return XML. Developers get back a basic XML payload such as:

<DescribeInstancesResponse xmlns="http://ec2.amazonaws.com/doc/2014-10-01/">

<requestId>fdcdcab1-ae5c-489e-9c33-4637c5dda355</requestId>

<reservationSet>

<item>

<reservationId>;r-1a2b3c4d</reservationId>

<ownerId>123456789012</ownerId>

<groupSet>

<item>

<groupId>sg-1a2b3c4d</groupId>

<groupName>my-security-group</groupName>

</item>

</groupSet>

<instancesSet>

<item>

<instanceId>i-1a2b3c4d</instanceId>

<imageId>ami-1a2b3c4d</imageId>

Breadth of services

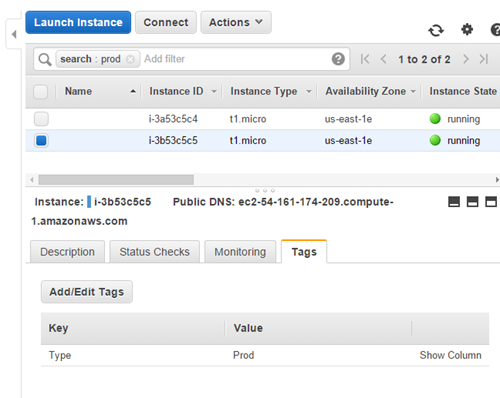

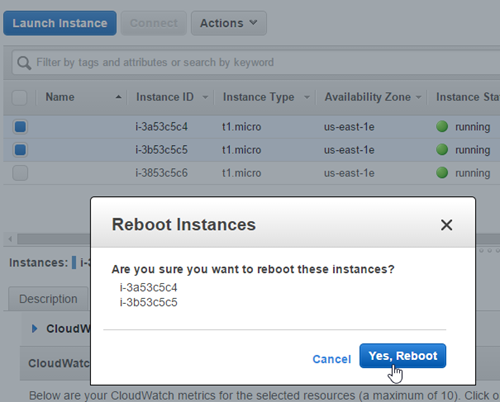

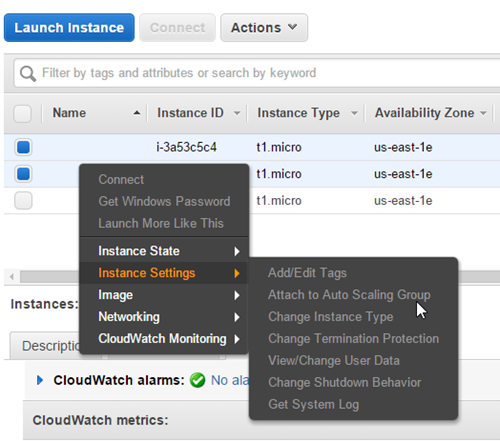

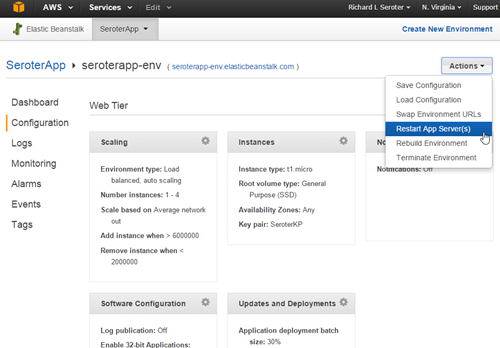

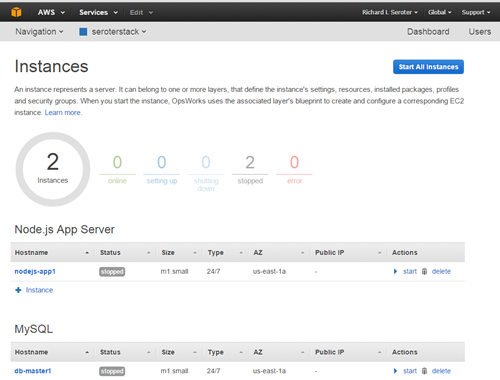

Each AWS service exposes an impressive array of operations. EC2 is no exception with well over 100. The API spans server provisioning and configuration, as well as network and storage setup.

I’m hard pressed to find anything in the EC2 management UI that isn’t available in the API set.

SDKs, tools, and documentation

AWS is known for its comprehensive documentation that stays up-to-date. The EC2 API documentation includes a list of operations, a basic walkthrough of creating API requests, parameter descriptions, and information about permissions.

SDKs give developers a quicker way to get going with an API, and AWS provides SDKs for Java, .NET, Node.js. PHP, Python and Ruby. Developers can find these SDKs in package management systems like npm (Node.js) and NuGet (.NET).

As you may expect, there are gobs of 3rd party tools that integrate with AWS. Whether it’s configuration management plugins for Chef or Ansible, or build automation tools like Terraform, you can expect to find AWS plugins.

Unique attributes

The AWS API is comprehensive with fine-grained operations. It also has a relatively unique security process (signature hashing) that may steer you towards the SDKs that shield you from the trickiness of correctly signing your request. Also, because EC2 is one of the first AWS services ever released, it’s using an older XML scheme. Newer services like DynamoDB or Kinesis offer a JSON syntax.

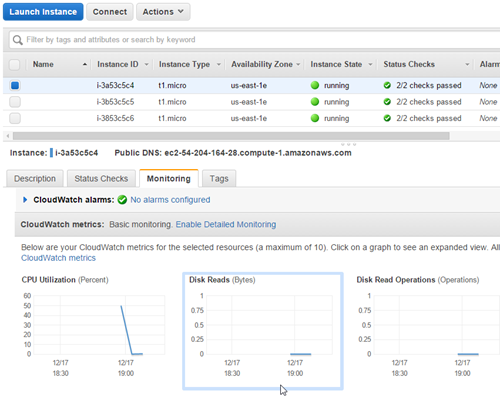

Amazon offers push-based notification through CloudWatch + SNS, so developers can get an HTTP push message when things like Autoscale events fire, or a performance alarm gets triggered.

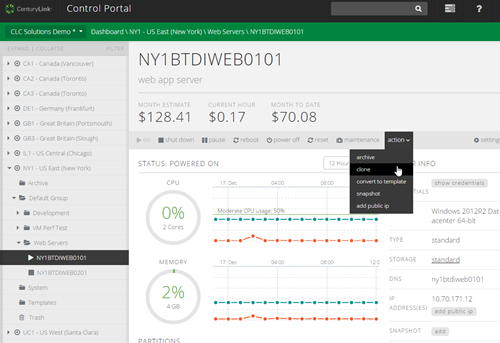

Global telecommunications and technology company CenturyLink offers a public cloud in regions around the world. The API has evolved from a SOAP/HTTP model (v1) to a fully RESTful one (v2).

Login mechanism

To use the CenturyLink Cloud API, developers send their platform credentials to a “login” endpoint and get back a reusable bearer token if the credentials are valid. That token is required for any subsequent API calls.

A request for token may look like:

POST https://api.ctl.io/v2/authentication/login HTTP/1.1

Host: api.ctl.io

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 54

{

"username": "[username]",

"password": "[password]"

}

A token (and role list) comes back with the API response, and developers use that token in the “Authorization” HTTP header for each subsequent API call.

GET https://api.ctl.io/v2/datacenters/RLS1/WA1 HTTP/1.1

Host: api.ctl.io

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 0

Authorization: Bearer [LONG TOKEN VALUE]

Request and response shape

The v2 API uses JSON for the request and response format. The legacy API uses XML or JSON with either SOAP or HTTP (don’t call it REST) endpoints.

To retrieve a single server in the v2 API, the developer sends a request to:

GET https://api.ctl.io/v2/servers/{accountAlias}/{serverId}

The responding JSON for most any service is verbose, and includes a number of links to related resources. For instance, in the example response payload below, notice that the caller can follow links to the specific alert policies attached to a server, billing estimates, and more.

{

"id": "WA1ALIASWB01",

"name": "WA1ALIASWB01",

"description": "My web server",

"groupId": "2a5c0b9662cf4fc8bf6180f139facdc0",

"isTemplate": false,

"locationId": "WA1",

"osType": "Windows 2008 64-bit",

"status": "active",

"details": {

"ipAddresses": [

{

"internal": "10.82.131.44"

}

],

"alertPolicies": [

{

"id": "15836e6219e84ac736d01d4e571bb950",

"name": "Production Web Servers - RAM",

"links": [

{

"rel": "self",

"href": "/v2/alertPolicies/alias/15836e6219e84ac736d01d4e571bb950"

},

{

"rel": "alertPolicyMap",

"href": "/v2/servers/alias/WA1ALIASWB01/alertPolicies/15836e6219e84ac736d01d4e571bb950",

"verbs": [

"DELETE"

]

}

]

],

"cpu": 2,

"diskCount": 1,

"hostName": "WA1ALIASWB01.customdomain.com",

"inMaintenanceMode": false,

"memoryMB": 4096,

"powerState": "started",

"storageGB": 60,

"disks":[

{

"id":"0:0",

"sizeGB":60,

"partitionPaths":[]

}

],

"partitions":[

{

"sizeGB":59.654,

"path":"C:\\"

}

],

"snapshots": [

{

"name": "2014-05-16.23:45:52",

"links": [

{

"rel": "self",

"href": "/v2/servers/alias/WA1ALIASWB01/snapshots/40"

},

{

"rel": "delete",

"href": "/v2/servers/alias/WA1ALIASWB01/snapshots/40"

},

{

"rel": "restore",

"href": "/v2/servers/alias/WA1ALIASWB01/snapshots/40/restore"

}

]

}

],

},

"type": "standard",

"storageType": "standard",

"changeInfo": {

"createdDate": "2012-12-17T01:17:17Z",

"createdBy": "user@domain.com",

"modifiedDate": "2014-05-16T23:49:25Z",

"modifiedBy": "user@domain.com"

},

"links": [

{

"rel": "self",

"href": "/v2/servers/alias/WA1ALIASWB01",

"id": "WA1ALIASWB01",

"verbs": [

"GET",

"PATCH",

"DELETE"

]

},

…{

"rel": "group",

"href": "/v2/groups/alias/2a5c0b9662cf4fc8bf6180f139facdc0",

"id": "2a5c0b9662cf4fc8bf6180f139facdc0"

},

{

"rel": "account",

"href": "/v2/accounts/alias",

"id": "alias"

},

{

"rel": "billing",

"href": "/v2/billing/alias/estimate-server/WA1ALIASWB01"

},

{

"rel": "statistics",

"href": "/v2/servers/alias/WA1ALIASWB01/statistics"

},

{

"rel": "scheduledActivities",

"href": "/v2/servers/alias/WA1ALIASWB01/scheduledActivities"

},

{

"rel": "alertPolicyMappings",

"href": "/v2/servers/alias/WA1ALIASWB01/alertPolicies",

"verbs": [

"POST"

]

}, {

"rel": "credentials",

"href": "/v2/servers/alias/WA1ALIASWB01/credentials"

},

]

}

Breadth of services

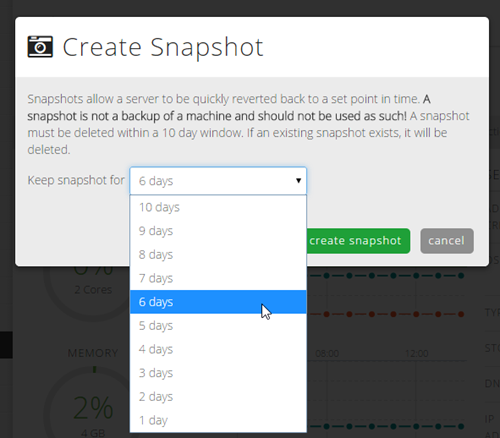

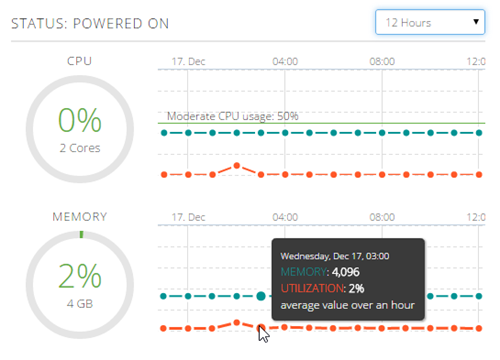

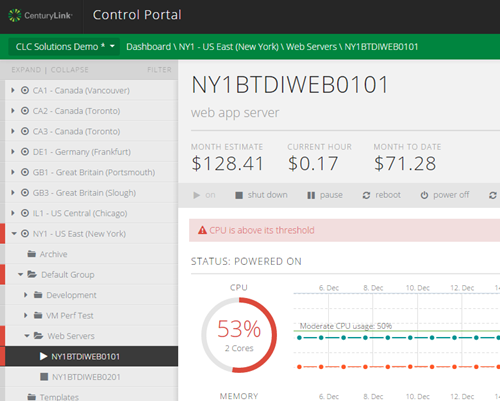

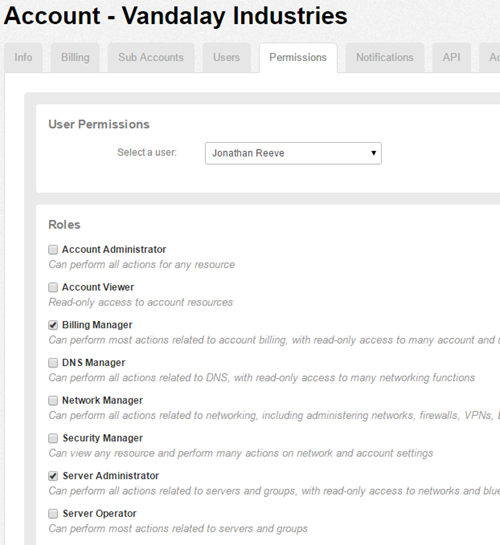

CenturyLink provides APIs for a majority of the capabilities exposed in the management UI. Developers can create and manage servers, networks, firewall policies, load balancer pools, server policies, and more.

SDKs, tools, and documentation

CenturyLink recently launched a Developer Center to collect all the developer content in one place. It points to the Knowledge Base of articles, API documentation, and developer-centric blog. The API documentation is fairly detailed with descriptions of operations, payloads, and sample calls. Users can also watch brief video walkthroughs of major platform capabilities.

There are open source SDKs for Java, .NET, Python, and PHP. CenturyLink also offers an Ansible module, and integrates with multi-cloud manager tool vRealize from VMware.

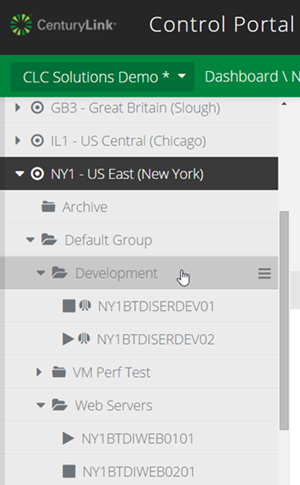

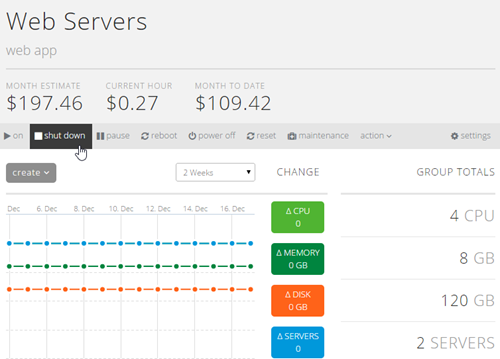

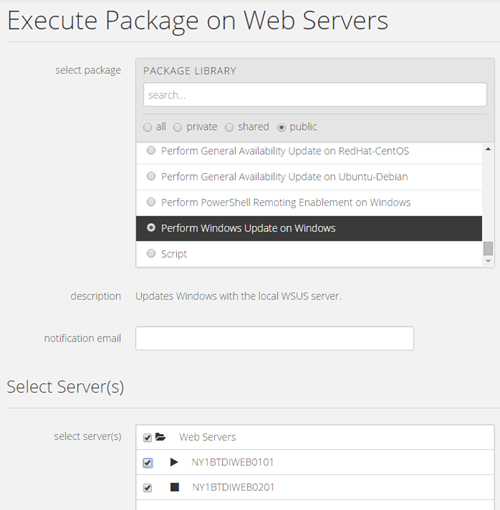

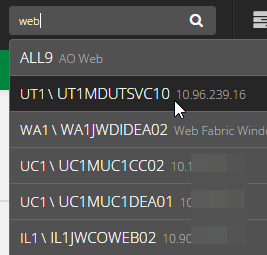

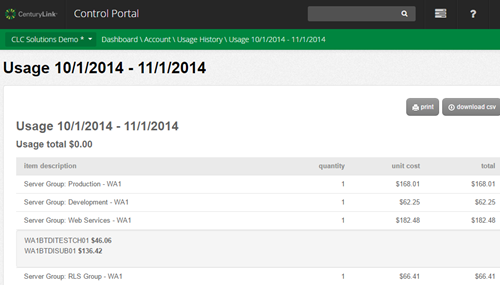

Unique attributes

The CenturyLink API provides a few unique things. The platform has the concept of “grouping” servers together. Via the API, you can retrieve the servers in a groups, or get the projected cost of a group, among other things. Also, collections of servers can be passed into operations, so a developer can reboot a set of boxes, or run a script against many boxes at once.

Somewhat similar to AWS, CenturyLink offers push-based notifications via webhooks. Developers get a near real-time HTTP notification when servers, users, or accounts are created/changed/deleted, and also when monitoring alarms fire.

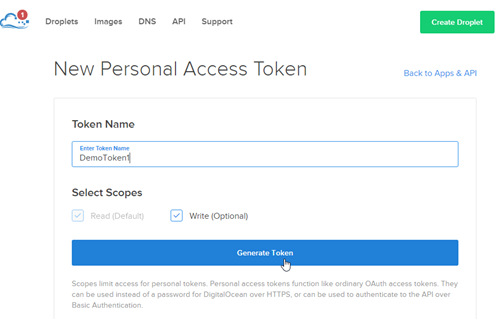

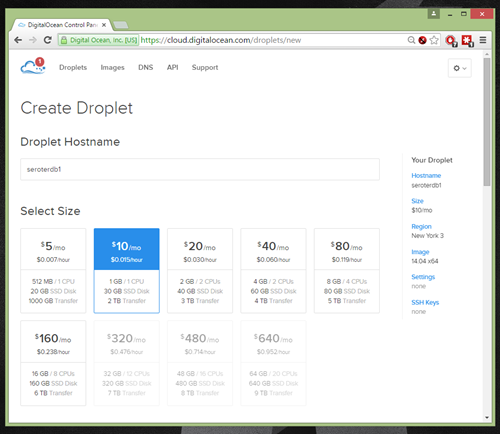

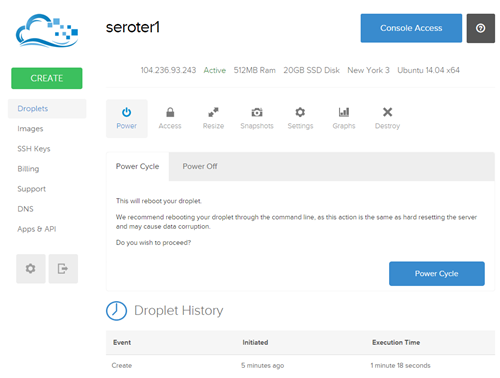

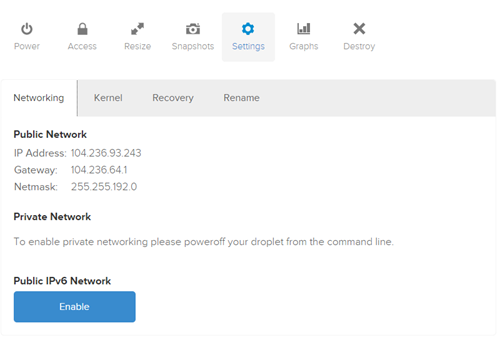

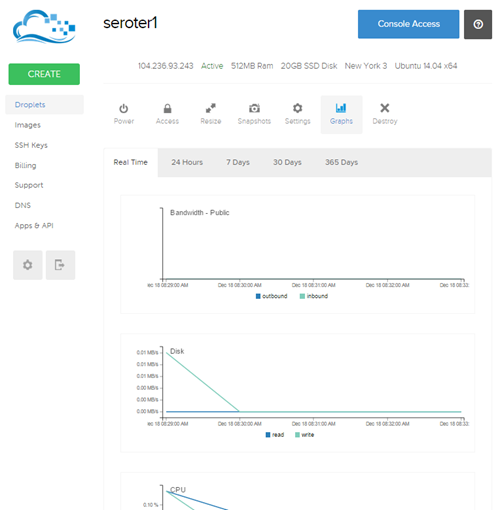

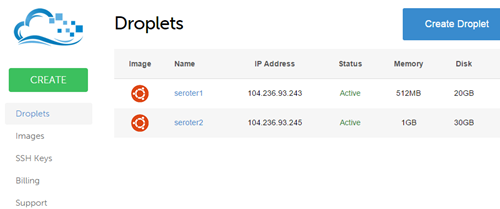

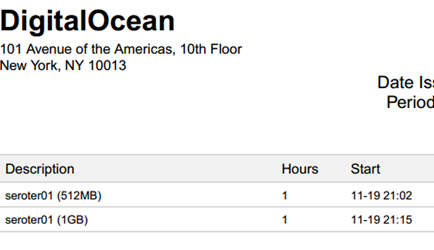

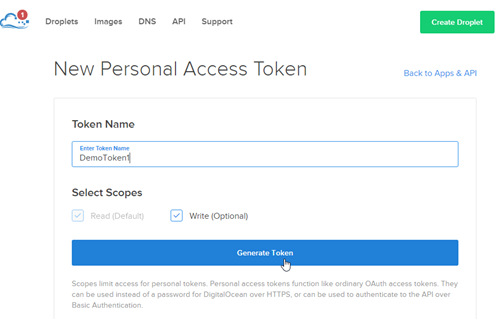

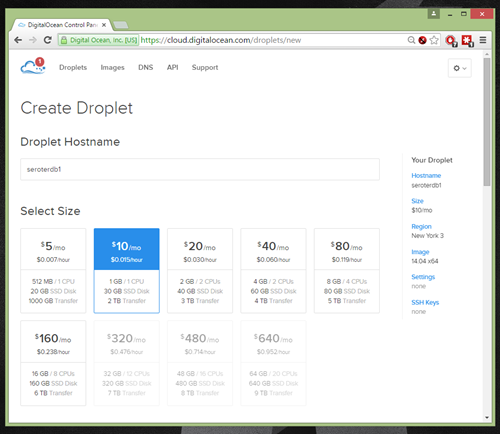

DigitalOcean heavily targets developers, so you’d expect a strong focus on their API. They have a v1 API (that’s deprecated and will shut down in November 2015), and a v2 API.

Login mechanism

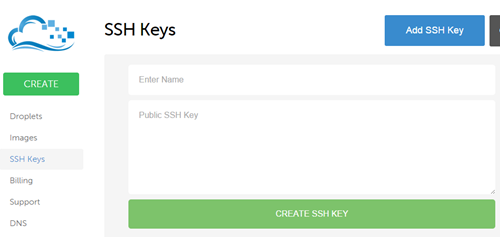

DigitalOcean authenticates users via OAuth. In the management UI, developers create OAuth tokens that can be for read, or read/write. These token values are only shown a single time (for security reasons), so developers must make sure to save it in a secure place.

Once you have this token, you can either send the bearer token in the HTTP header, or, (and it’s not recommended) use it in an HTTP basic authentication scenario. A typical curl request looks like:

curl -X $HTTP_METHOD -H "Authorization: Bearer $TOKEN" "https://api.digitalocean.com/v2/$OBJECT"

Request and response shape

The DigitalOcean API is RESTful with JSON payloads. Developers throw typical HTTP verbs (GET/DELETE/PUT/POST/HEAD) against the endpoints. Let’s say that I wanted to retrieve a specific droplet – a “droplet” in DigitalOcean is equivalent to a virtual machine – via the API. I’d send a request to:

https://api.digitalocean.com/v2/droplets/[dropletid]

The response from such a request comes back as verbose JSON.

{

"droplet": {

"id": 3164494,

"name": "example.com",

"memory": 512,

"vcpus": 1,

"disk": 20,

"locked": false,

"status": "active",

"kernel": {

"id": 2233,

"name": "Ubuntu 14.04 x64 vmlinuz-3.13.0-37-generic",

"version": "3.13.0-37-generic"

},

"created_at": "2014-11-14T16:36:31Z",

"features": [

"ipv6",

"virtio"

],

"backup_ids": [

],

"snapshot_ids": [

7938206

],

"image": {

"id": 6918990,

"name": "14.04 x64",

"distribution": "Ubuntu",

"slug": "ubuntu-14-04-x64",

"public": true,

"regions": [

"nyc1",

"ams1",

"sfo1",

"nyc2",

"ams2",

"sgp1",

"lon1",

"nyc3",

"ams3",

"nyc3"

],

"created_at": "2014-10-17T20:24:33Z",

"type": "snapshot",

"min_disk_size": 20

},

"size": {

},

"size_slug": "512mb",

"networks": {

"v4": [

{

"ip_address": "104.131.186.241",

"netmask": "255.255.240.0",

"gateway": "104.131.176.1",

"type": "public"

}

],

"v6": [

{

"ip_address": "2604:A880:0800:0010:0000:0000:031D:2001",

"netmask": 64,

"gateway": "2604:A880:0800:0010:0000:0000:0000:0001",

"type": "public"

}

]

},

"region": {

"name": "New York 3",

"slug": "nyc3",

"sizes": [

"32gb",

"16gb",

"2gb",

"1gb",

"4gb",

"8gb",

"512mb",

"64gb",

"48gb"

],

"features": [

"virtio",

"private_networking",

"backups",

"ipv6",

"metadata"

],

"available": true

}

}

}

Breadth of services

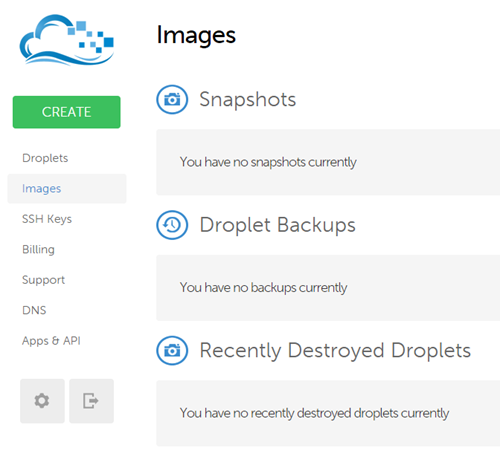

DigitalOcean says that “all of the functionality that you are familiar with in the DigitalOcean control panel is also available through the API,” and that looks to be pretty accurate. DigitalOcean is known for their no-frills user experience, and with the exception of account management features, the API gives you control over most everything. Create droplets, create snapshots, move snapshots between regions, manage SSH keys, manage DNS records, and more.

SDKs, tools, and documentation

Developers can find lots of open source projects from DigitalOcean that favor Go and Ruby. There are a couple of official SDK libraries, and a whole host of other community supported ones. You’ll find ones for Ruby, Go, Python, .NET, Java, Node, and more.

DigitalOcean does a great job at documentation (with samples included), and also has a vibrant set of community contributions that apply to virtual any (cloud) environment. The contributed list of tutorials is fantastic.

Being so developer-centric, DigitalOcean can be found as a supported module in many 3rd party toolkits. You’ll find friendly extensions for Vagrant, Juju, SaltStack and much more.

Unique attributes

What stands out for me regarding DigitalOcean is the quality of their documentation, and complete developer focus. The API itself is fairly standard, but it’s presented in a way that’s easy to grok, the the ecosystem around the service is excellent.

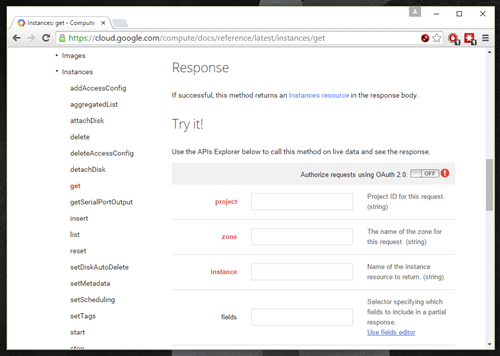

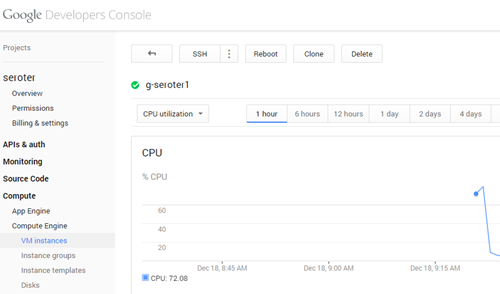

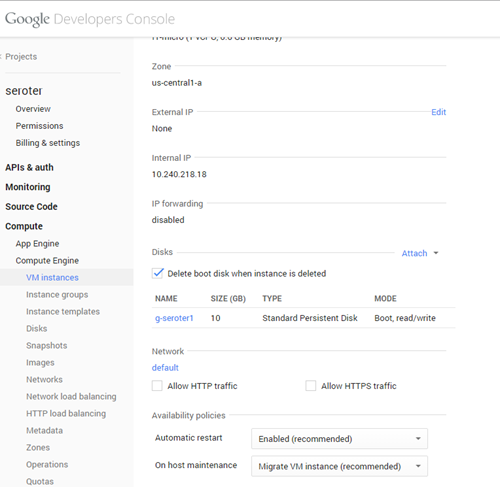

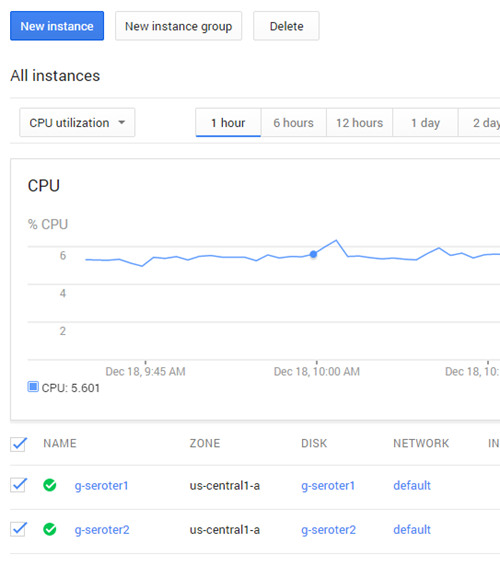

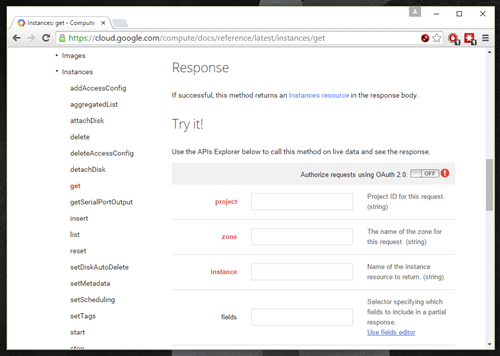

Google has lots of API-enabled services, and GCE is no exception.

Login mechanism

Google uses OAuth 2.0 and access tokens. Developers register their apps, define a scope, and request a short-lived access token. There are different flows depending on if you’re working with web applications (with interactive user login) versus service accounts (consent not required).

If you go the service account way, then you’ve got to generate a JSON Web Token (JWT) through a series of encoding and signing steps. The payload to GCE for getting a valid access token looks like:

POST /oauth2/v3/token HTTP/1.1

Host: www.googleapis.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

grant_type=urn%3Aietf%3Aparams%3Aoauth%3Agrant-type%3Ajwt-bearer&assertion=eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpc3MiOiI3NjEzMjY3O…

Request and response shape

The Google API is RESTful and passes JSON messages back and forth. Operations map to HTTP verbs, and URIs reflect logical resources paths (as much as the term “methods” made me shudder). If you want a list of virtual machine instances, you’d send a request to:

https://www.googleapis.com/compute/v1/projects/<var>project</var>/global/images

The response comes back as JSON:

{

"kind": "compute#imageList",

"selfLink": <var>string</var>,

"id": <var>string</var>,

"items": [</pre>

{

"kind": "compute#image",

"selfLink": <var>string</var>,

"id": <var>unsigned long</var>,

"creationTimestamp": <var>string</var>,

"name": <var>string</var>,

"description": <var>string</var>,

"sourceType": <var>string</var>,

"rawDisk": {

"source": <var>string</var>,

"sha1Checksum": <var>string</var>,

"containerType": <var>string</var>

},

"deprecated": {

"state": <var>string</var>,

"replacement": <var>string</var>,

"deprecated": <var>string</var>,

"obsolete": <var>string</var>,

"deleted": <var>string</var>

},

"status": <var>string</var>,

"archiveSizeBytes": <var>long</var>,

"diskSizeGb": <var>long</var>,

"sourceDisk": <var>string</var>,

"sourceDiskId": <var>string</var>,

"licenses": [

<var>string</var>

]

}],

"nextPageToken": <var>string</var>

}

Breadth of services

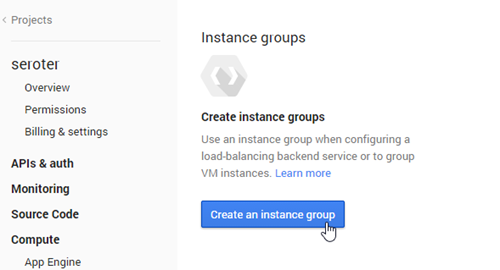

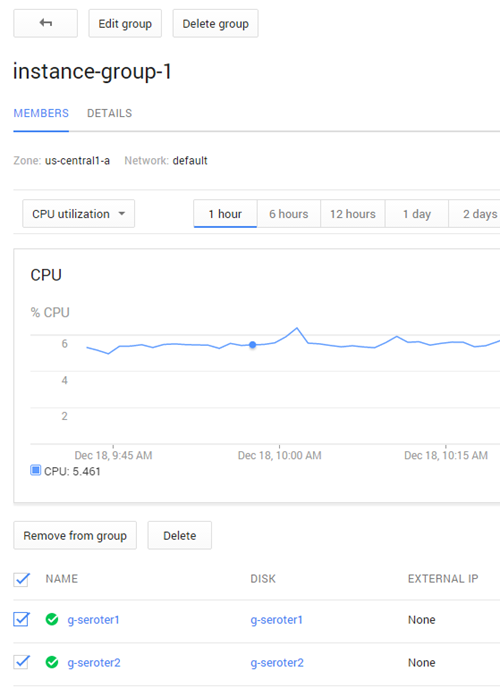

The GCE API spans a lot of different capabilities that closely match what they offer in their management UI. There’s the base Compute API – this includes operations against servers, images, snapshots, disks, network, VPNs, and more – as well as beta APIs for Autoscalers and instance groups. There’s also an alpha API for user and account management.

SDKs, tools, and documentation

Google offers a serious set of client libraries. You’ll find libraries and dedicated documentation for Java, .NET, Go, Ruby, Objective C, Python and more.

The documentation for GCE is solid. Not only will you find detailed API specifications, but also a set of useful tutorials for setting up platforms (e.g. LAMP stack) or workflows (e.g. Jenkins + Packer + Kubernetes) on GCE.

Google lists out a lot of tools that natively integrate with the cloud service. The primary focus here is configuration management tools, with specific callouts for Chef, Puppet, Ansible, and SaltStack.

Unique attributes

GCE has a good user management API. They also have a useful batching capability where you can bundle together multiple related or unrelated calls into a single HTTP request. I’m also impressed by Google’s tools for trying out API calls ahead of time. There’s the Google-wide OAuth 2.0 playground where you can authorize and try out calls. Even better, for any API operation in the documentation, there’s a “try it” section at the bottom where you can call the endpoint and see it in action.

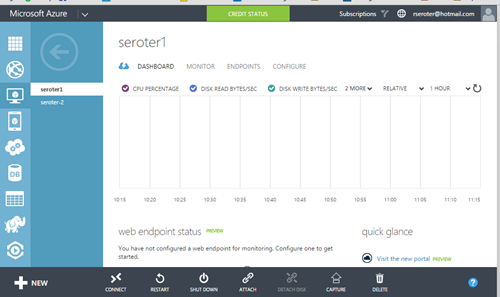

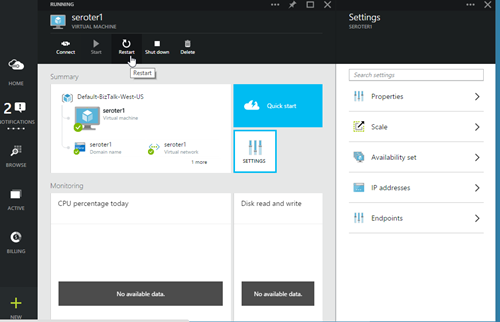

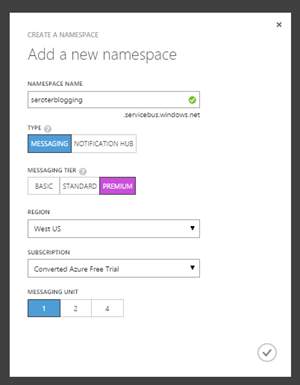

Microsoft added virtual machines to its cloud portfolio a couple years ago, and has API-enabled most of their cloud services.

Login mechanism

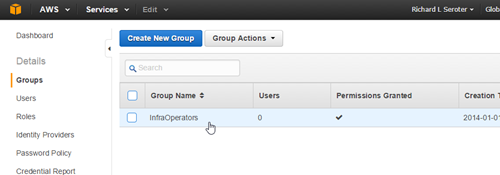

One option for managing Azure components programmatically is via the Azure Resource Manager. Any action you perform on a resource requires the call to be authenticated with Azure Active Directory. To do this, you have to add your app to an Azure Active Directory tenant, set permissions for the app, and get a token used for authenticating requests.

The documentation says that you can set up this the Azure CLI or PowerShell commands (or the management UI). The same docs show a C# example of getting the JWT token back from the management endpoint.

public static string GetAToken()

{

var authenticationContext = new AuthenticationContext("https://login.windows.net/{tenantId or tenant name}");

var credential = new ClientCredential(clientId: "{application id}", clientSecret: {application password}");

var result = authenticationContext.AcquireToken(resource: "https://management.core.windows.net/", clientCredential:credential);

if (result == null) {

throw new InvalidOperationException("Failed to obtain the JWT token");

}

string token = result.AccessToken;

return token;

}

Microsoft also offers a direct Service Management API for interacting with most Azure items. Here you can authenticate using Azure Active Directory or X.509 certificates.

Request and response shape

The Resource Manager API appears RESTful and works with JSON messages. In order to retrieve the details about a specific virtual machine, you send a request to:

http://maagement.azure.com/subscriptions/{subscription-id}/resourceGroups/{resource-group-name}/providers/Microsoft.Compute/virtualMachines/{vm-name}?api-version={api-version

The response JSON is fairly basic, and doesn’t tell you much about related services (e.g. networks or load balancers).

{

"id":"/subscriptions/########-####-####-####-############/resourceGroups/{resourceGroupName}/providers/Microsoft.Compute/virtualMachines/{virtualMachineName}",

"name":"virtualMachineName”,

" type":"Microsoft.Compute/virtualMachines",

"location":"westus",

"tags":{

"department":"finance"

},

"properties":{

"availabilitySet":{

"id":"/subscriptions/########-####-####-####-############/resourceGroups/{resourceGroupName}/providers/Microsoft.Compute/availabilitySets/{availabilitySetName}"

},

"hardwareProfile":{

"vmSize":"Standard_A0"

},

"storageProfile":{

"imageReference":{

"publisher":"MicrosoftWindowsServerEssentials",

"offer":"WindowsServerEssentials",

"sku":"WindowsServerEssentials",

"version":"1.0.131018"

},

"osDisk":{

"osType":"Windows",

"name":"osName-osDisk",

"vhd":{

"uri":"http://storageAccount.blob.core.windows.net/vhds/osDisk.vhd"

},

"caching":"ReadWrite",

"createOption":"FromImage"

},

"dataDisks":[

]

},

"osProfile":{

"computerName":"virtualMachineName",

"adminUsername":"username",

"adminPassword":"password",

"customData":"",

"windowsConfiguration":{

"provisionVMAgent":true,

"winRM": {

"listeners":[{

"protocol": "https",

"certificateUrl": "[parameters('certificateUrl')]"

}]

},

“additionalUnattendContent”:[

{

“pass”:“oobesystem”,

“component”:“Microsoft-Windows-Shell-Setup”,

“settingName”:“FirstLogonCommands|AutoLogon”,

“content”:“<XML unattend content>”

} "enableAutomaticUpdates":true

},

"secrets":[

]

},

"networkProfile":{

"networkInterfaces":[

{

"id":"/subscriptions/########-####-####-####-############/resourceGroups/CloudDep/providers/Microsoft.Network/networkInterfaces/myNic"

}

]

},

"provisioningState":"succeeded"

}

}

The Service Management API is a bit different. It’s also RESTful, but works with XML messages (although some of the other services like Autoscale seem to work with JSON). If you wanted to create a VM deployment, you’d send an HTTP POST request to:

https://management.core.windows.net/<subscription-id>/services/hostedservices/<cloudservice-name>/deployments

The result is an extremely verbose XML payload.

Breadth of services

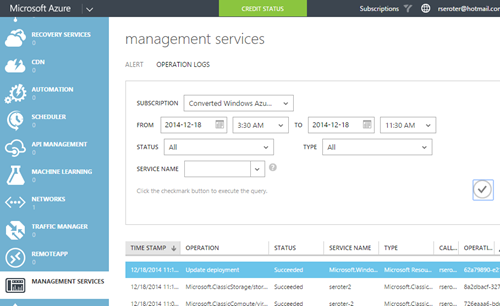

In addition to an API for virtual machine management, Microsoft has REST APIs for virtual networks, load balancers, Traffic Manager, DNS, and more. The Service Management API appears to have a lot more functionality than the Resource Manager API.

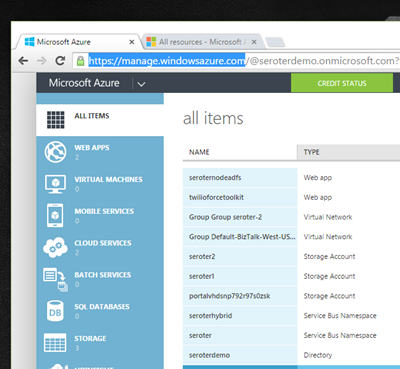

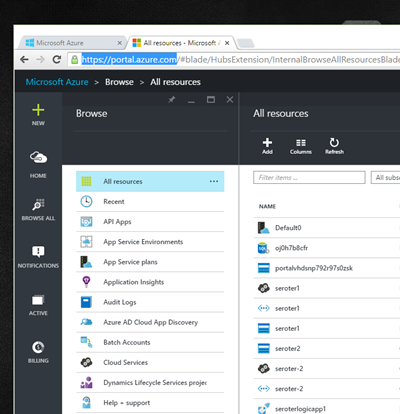

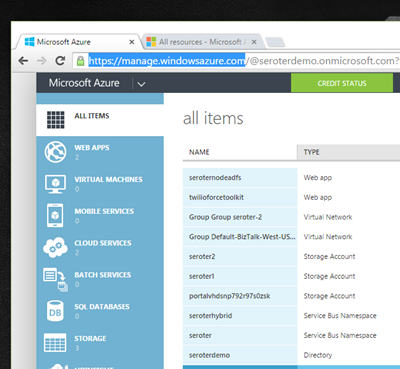

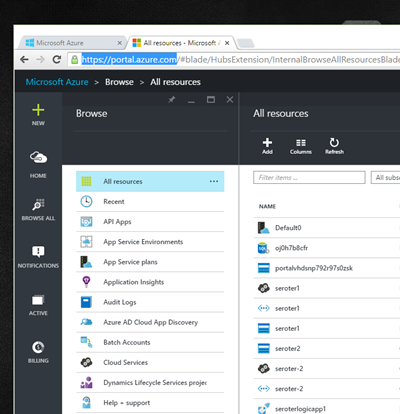

Microsoft is stuck with a two portal user environment where the officially supported one (at https://manage.windowsazure.com) has different features and functions than the beta one (https://portal.azure.com). It’s been like this for quite a while, and hopefully they cut over to the new one soon.

SDKs, tools, and documentation

Microsoft provides lots of options on their SDK page. Developers can interact with the Azure API using .NET, Java, Node.js, PHP, Python, Ruby, and Mobile (iOS, Android, Windows Phone), and it appears that each one uses the Service Management APIs to interact with virtual machines. Frankly, the documentation around this is a bit confusing. The documentation about the virtual machines service is ok, and provides a handful of walkthroughs to get you started.

The core API documentation exists for both the Service Management API, and the Azure Resource Manager API. For each set of documentation, you can view details of each API call. I’m not a fan of the the navigation in Microsoft API docs. It’s not easy to see the breadth of API operations as the focus is on a single service at a time.

Microsoft has a lot of support for virtual machines in the ecosystem, and touts integration with Chef, Ansible, and Docker,

Unique attributes

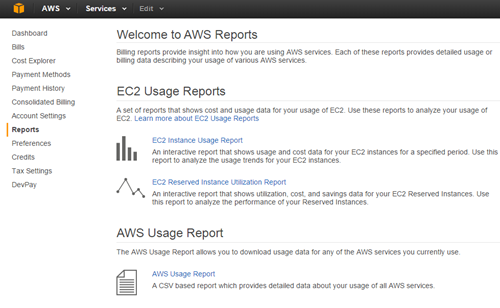

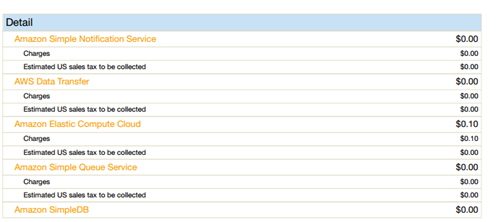

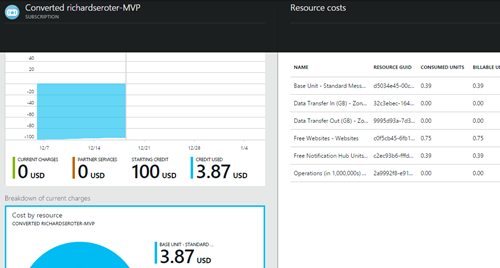

Besides being a little confusing (which APIs to use), the Azure API is pretty comprehensive (on the Service Management side). Somewhat uniquely, the Resource Manager API has a (beta) billing API with data about consumption and pricing. While I’ve complained a bit here about Resource Manager and conflicting APIs, it’s actually a pretty useful thing. Developers can use the resource manager concept (and APIs) to group related resources and deliver access control and templating.

Also, Microsoft bakes in support for Azure virtual machines in products like Azure Site Recovery.

Summary

The common thing you see across most cloud APIs is that they provide solid coverage of the features the user can do in the vendor’s graphical UI. We also saw that more and more attention is being paid to SDKs and documentation to help developers get up and running. AWS has been in the market the longest, so you see maturity and breadth in their API, but also a heavier interface (authentication, XML payloads). CenturyLink and Google have good account management APIs, and Azure’s billing API is a welcome addition to their portfolio. Amazon, CenturyLink, and Google have fairly verbose API responses, and CenturyLink is the only one with a hypermedia approach of linking to related resources. Microsoft has a messier API story than I would have expected, and developers will be better off using SDKs!

What do you think? Do you use the native APIs of cloud providers, or prefer to go through SDKs or brokers?

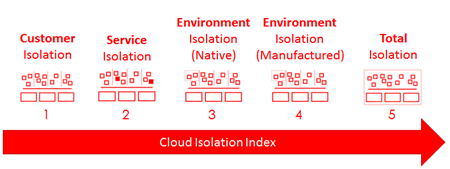

You’re seeing a new crop of solutions here, and I like this trend.

You’re seeing a new crop of solutions here, and I like this trend.  Also, our customers use

Also, our customers use  Most clouds offer a vast ecosystem of 3rd party open source and commercial appliances. Create isolated networks with an overlay solution, encrypt workloads at the host level, stand up self-managed database solutions, and much more. Look at something like

Most clouds offer a vast ecosystem of 3rd party open source and commercial appliances. Create isolated networks with an overlay solution, encrypt workloads at the host level, stand up self-managed database solutions, and much more. Look at something like