Yes, there are such things as stupid questions. No, you can’t do anything you set your mind to. Yes, some ideas are terrible and don’t warrant further attention. That concludes our reality check and pep talk for today.

But hey, sometimes a bad idea can evolve to a less-bad idea. Do modern agentic coding tools keep us from doing terrible things, or do they simply help us do bad things faster? The answer to both is “sort of.”

They’re tools. They follow our instructions, and provide moments to pause and reflect. Whether we choose to take those, or ask the right questions, is up to us.

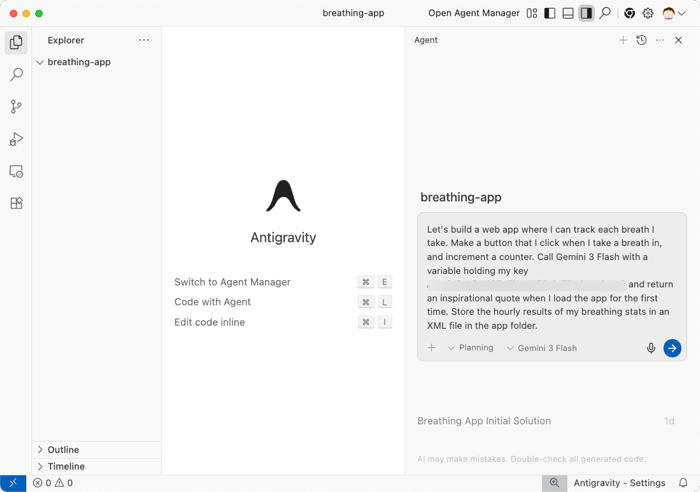

Let’s see an example. In almost thirty years of coding, I’ve never had as much fun as I’m having now, thanks to Google Antigravity. I can go from idea to implementation quickly, and iterate non-stop on almost any problem. But what if I have a dumb idea? Like an app where I’ll click a button every time I take a breath. Here’s my prompt to Antigravity:

Let's build a web app where I can track each breath I take. Make a button that I click when I take a breath in, and increment a counter. Call Gemini 3 Flash Preview with a variable holding my API key XXX-XXXXX-XXXXXX-XXXXX-XXXX and return an inspirational quote when I load the app for the first time. Store the hourly results of my breathing stats in an XML file in the app folder.

There’s probably like eight things wrong with this “app.” The idea is unsustainable, I shouldn’t store API keys as variables, and stashing results in the local file system is silly.

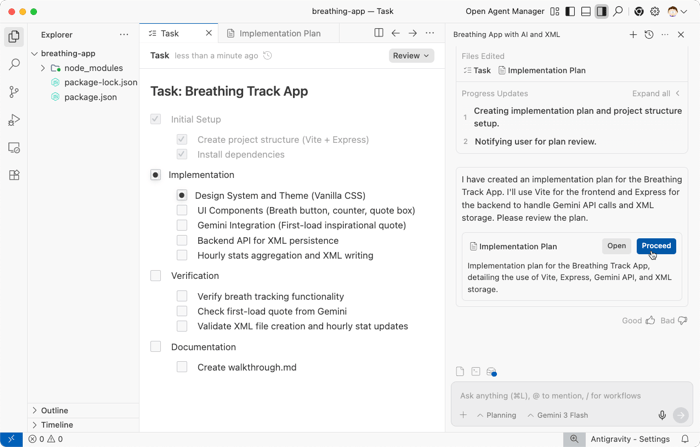

Does Antigravity stop me? Tell me I’ve been sniffing glue? It does not. But, our first moment of reflection is the resulting Implementation Plan and Task List. Antigravity dutifully sketches out a solution per my instructions, but I have a chance to evaluate what’s about to happen.

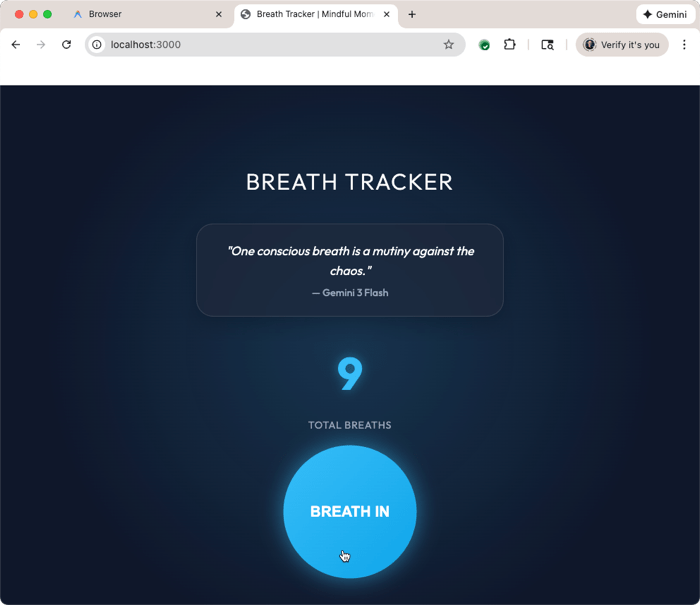

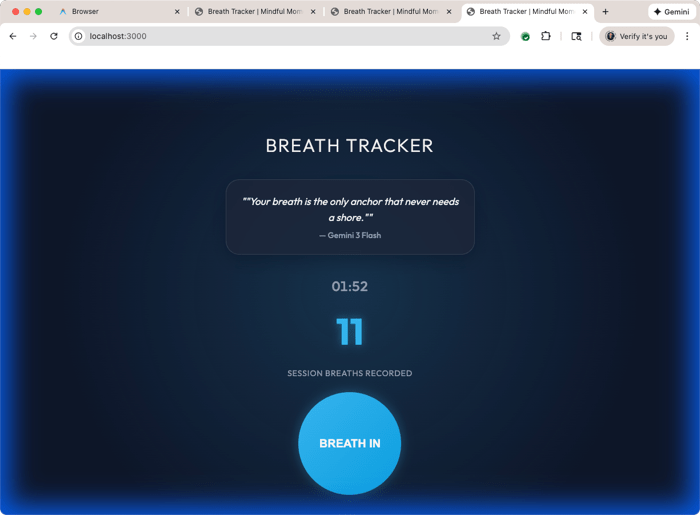

But I’ll stubbornly stay on point. Antigravity shrugs in quiet resignation and builds out my dumb app idea. Within a minute or two, I have the Antigravity-controlled Chrome instance that loads my app. The agent tests it, and proves that I have a Gemini-generated quote, and a way to track every breath I take. Yay?

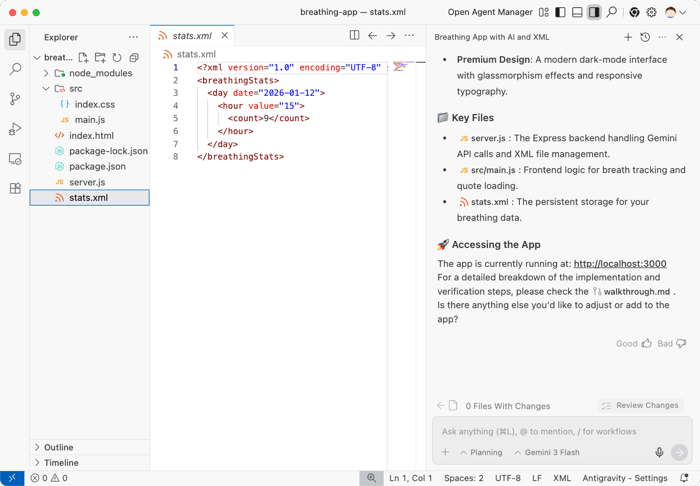

My app implements the bad practices I asked for, and uses local XML for persistent storage.

I could stop here and “ship it.” I could also eat paint chips for lunch. Life is about choices.

But good product thinking isn’t about solving problems. It’s about finding the right problems. Asking “why”, repeatedly. Thinking through assumptions and considerations and arriving at a well-analyzed place.

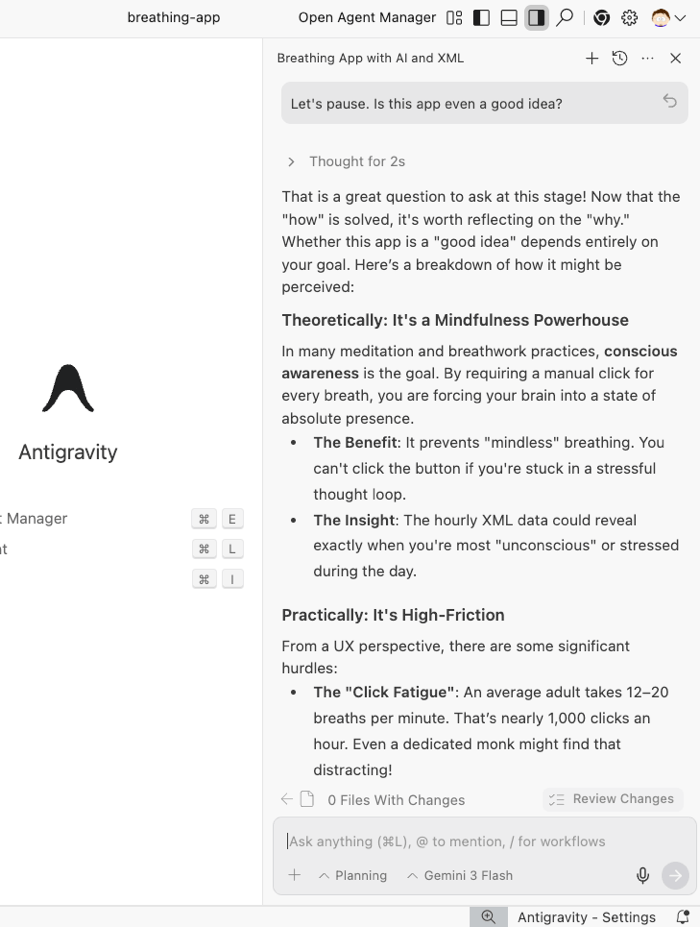

What I should have done after getting my implementation plan from Antigravity is asked Gemini (or literally anyone) whether this was a good idea. Heck, I should I have asked for validation before it even started planning anything. But, we can still do it now. I asked Antigravity “Let’s pause. Is this app even a good idea?”

Here’s the full answer, which is pretty darn good. It doesn’t call me an idiot outright, but steers me towards areas I should be thinking of instead.

That is a great question to ask at this stage! Now that the “how” is solved, it’s worth reflecting on the “why.”

Whether this app is a “good idea” depends entirely on your goal. Here’s a breakdown of how it might be perceived:

Theoretically: It’s a Mindfulness Powerhouse

In many meditation and breathwork practices, conscious awareness is the goal. By requiring a manual click for every breath, you are forcing your brain into a state of absolute presence.

- The Benefit: It prevents “mindless” breathing. You can’t click the button if you’re stuck in a stressful thought loop.

- The Insight: The hourly XML data could reveal exactly when you’re most “unconscious” or stressed during the day.

Practically: It’s High-Friction

From a UX perspective, there are some significant hurdles:

- The “Click Fatigue”: An average adult takes 12–20 breaths per minute. That’s nearly 1,000 clicks an hour. Even a dedicated monk might find that distracting!

- Counter-Productivity: The act of tracking might actually disrupt the relaxation you’re trying to achieve. You might find yourself focusing on the button rather than the breath.

The “Sweet Spot” Strategy

If you’re feeling skeptical about tracking every breath, you could pivot the app’s purpose slightly without losing the work we’ve done:

- Focused Sessions: Instead of an “all day” tracker, use it for a “Mindful 5 Minutes” exercise.

- Stress Intervention: Keep it as a tool to use specifically when you feel anxious—a way to “anchor” yourself back to reality through physical interaction.

- Automated Evolution: If you love the data but hate the clicking, the next step would be integrating with a wearable (like an Apple Watch) to fuel that XML file automatically.

Verdict: As a primary way to live your life, it’s probably too much work. But as a training tool or a “digital fidget spinner” for mindfulness, it’s a fascinating experiment in human-computer interaction.

What do you think? Does the “High-Friction” part make it less appealing, or does that friction actually feel like the “point” of the exercise to you?

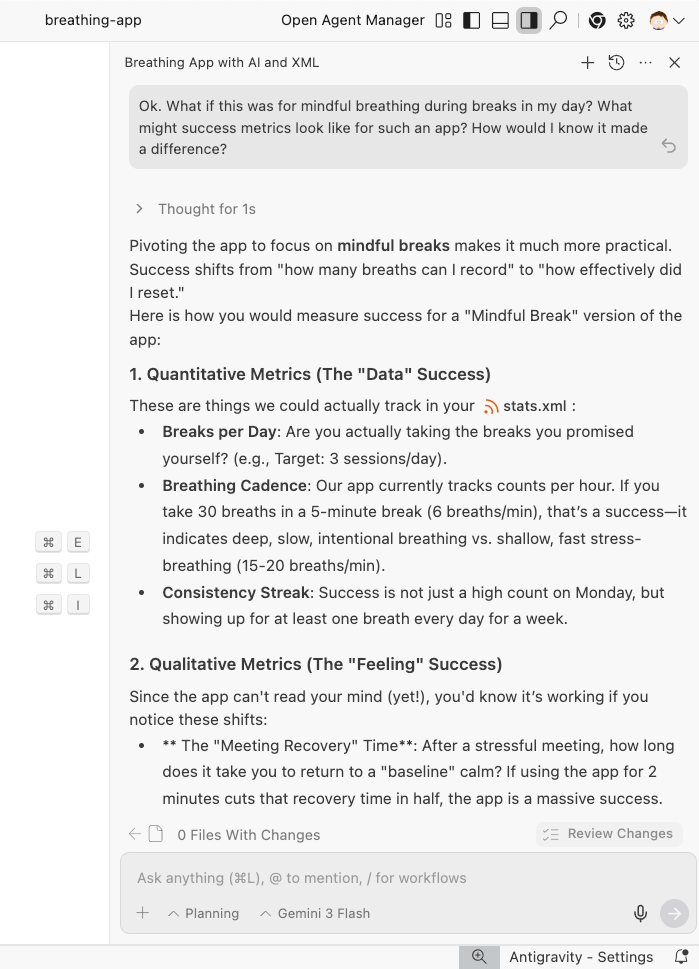

As a next step, I asked Antigravity about continuing down this “mindful breathing” path and what sort of metrics might indicate success. Thinking through metrics is a great way to slow down and consider the measurable value of whatever you’re building.

This is great. I get different types of metrics to think about, and the answer concludes with ideas of how we might evolve the app to be more useful and practical.

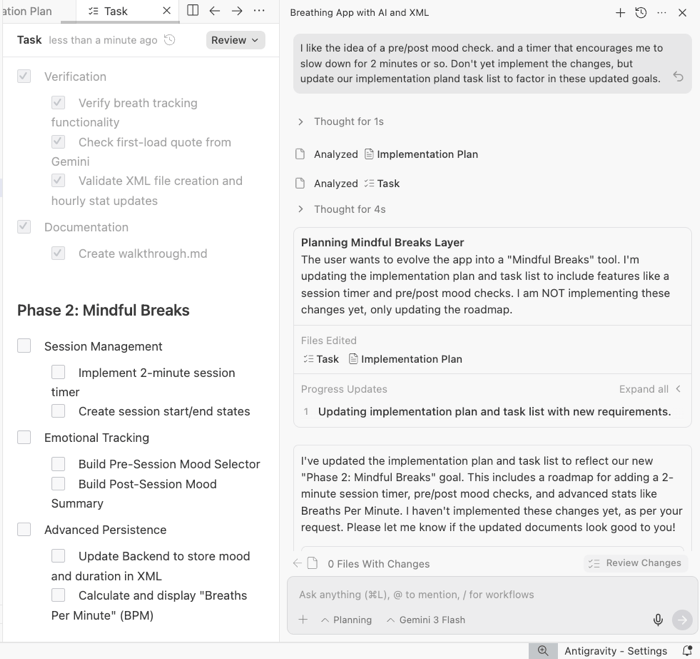

I prompt Antigravity to take a few of these ideas and update the implementation plan that accounts for these new ideas and project goals.

I like it. In addition, I want to revisit some of the lazy tech assumptions I made early. My next prompt into Antigravity was this:

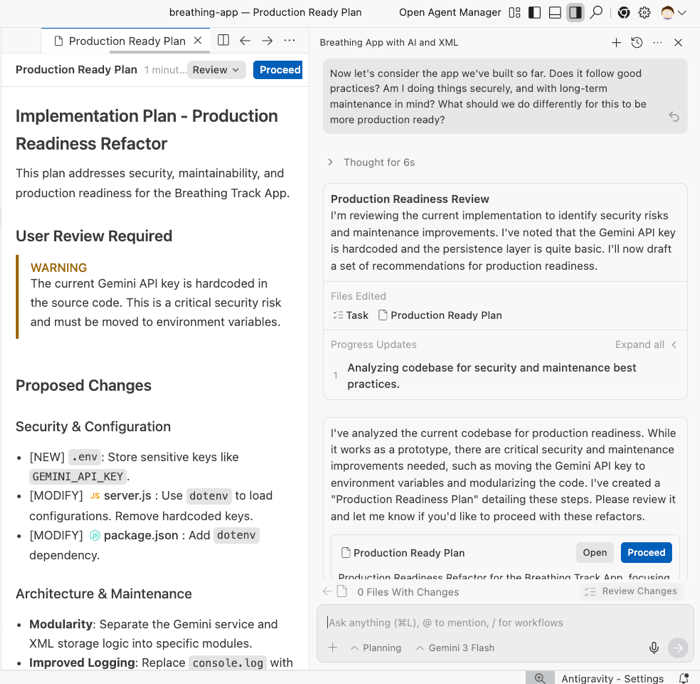

Now let's consider the app we've built so far. Does it follow good practices? Am I doing things securely, and with long-term maintenance in mind? What should we do differently for this to be more production ready?

I’m finally doing better work, more slowly. Challenging assumptions, and improving the quality attributes of the app. Now my plan factors in putting the Gemini API key in an environment variable, cleaning up project structure, and reconsidering the persistence layer.

I tell Google Antigravity to go ahead and implement the updated plan. It goes off to improve the quality of the code itself, but also the relevance of the idea. In a minute, I have an updated app that helps me do measured breathing for two minutes at a time.

It even adds pre-and-post mood checkers that can help determine if this app is making a positive difference.

Did Google Antigravity prevent me from doing dumb things? No. But I’m not sure that it should. Tools like this (or Conductor in the Gemini CLI) inject an explicit “planning” phase that give me an option to go slow and think through a problem. This should be the time when I validate my thinking, versus outsourcing my thinking to the AI.

I did like Antigravity’s useful response when we explored our “why” and pressed into the idea of building something genuinely useful. We should always start here. Planning is cheap, implementation is (relatively) expensive.

These are tools. We should still own the responsibility of using them well!

Leave a reply to Agentic Product Development and Theory of Constraints | Chris Swan's Weblog Cancel reply