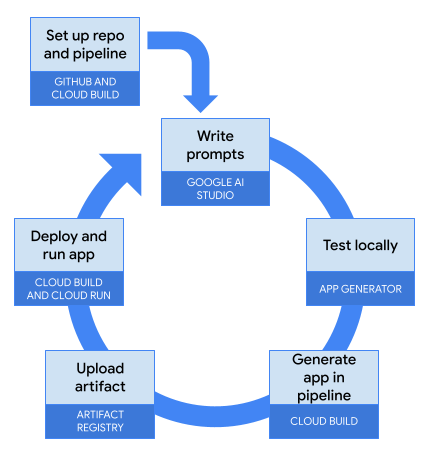

I can’t remember who mentioned this idea to me. It might have been a customer, colleague, internet rando, or voice in my head. But the idea was whether you could use source control for the prompts, and leverage an LLM to dynamically generate all the app code each time you run a build. That seems bonkers for all sorts of reasons, but I wanted to see if it was technically feasible.

Should you do this for real apps? No, definitely not yet. The non-deterministic nature of LLMs means you’d likely experience hard-to-find bugs, unexpected changes on each build, and get yelled at by regulators when you couldn’t prove reproducibility in your codebase. When would you use something like this? I’m personally going to use this to generate stub apps to test an API or database, build demo apps for workshops or customer demos, or to create a component for a broader architecture I’m trying out.

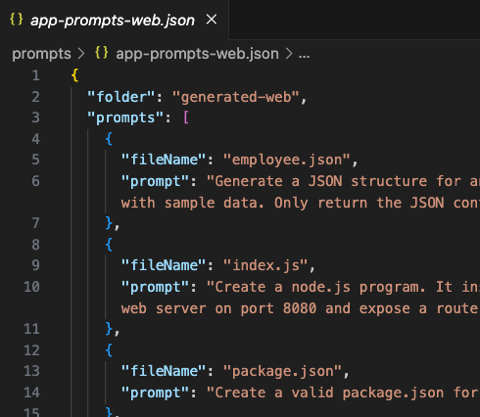

tl;dr I built an AI-based generator that takes a JSON file of prompts like this and creates all the code. I call this generator from a CI pipeline which means that I can check in (only) the prompts to GitHub, and end up with a running app in the cloud.

{

"folder": "generated-web",

"prompts": [

{

"fileName": "employee.json",

"prompt": "Generate a JSON structure for an object with fields for id, full name, state date, and office location. Populate it with sample data. Only return the JSON content and nothing else."

},

{

"fileName": "index.js",

"prompt": "Create a node.js program. It instantiates an employee object that looks like the employee.json structure. Start up a web server on port 8080 and expose a route at /employee return the employee object defined earlier."

},

{

"fileName": "package.json",

"prompt": "Create a valid package.json for this node.js application. Do not include any comments in the JSON."

},

{

"fileName": "Dockerfile",

"prompt": "Create a Dockerfile for this node.js application that uses a minimal base image and exposes the app on port 8080."

}

]

}

In this post, I’ll walk through the steps of what a software delivery workflow such as this might look like, and how I set up each stage. To be sure, you’d probably make different design choices, write better code, and pick different technologies. That’s cool; this was mostly an excuse for me to build something fun.

Before explaining this workflow, let me first show you the generator itself and how it works.

Building an AI code generator

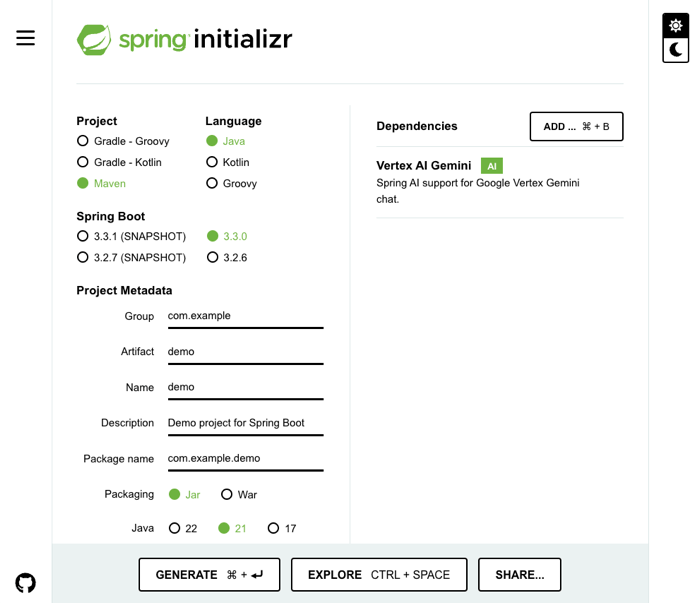

There are many ways to build this. An AI framework makes it easier, and I chose Spring AI because I wanted to learn how to use it. Even though this is a Java app, it generates code in any programming language.

I began at Josh Long’s second favorite place on the Internet, start.spring.io. Here I started my app using Java 21, Maven, and the Vertex AI Gemini starter, which pulls in Spring AI.

My application properties point at my Google Cloud project and I chose to use the impressive new Gemini 1.5 Flash model for my LLM.

spring.application.name=demo

spring.ai.vertex.ai.gemini.projectId=seroter-project-base

spring.ai.vertex.ai.gemini.location=us-central1

spring.ai.vertex.ai.gemini.chat.options.model=gemini-1.5-flash-001

My main class implements the CommandLineRunner interface and expects a single parameter, which is a pointer to a JSON file containing the prompts. I also have a couple of classes that define the structure of the prompt data. But the main generator class is where I want to spend some time.

Basically, for each prompt provided to the app, I look for any local files to provide as multimodal context into the request (so that the LLM can factor in any existing code as context when it processes the prompt), call the LLM, extract the resulting code from the Markdown wrapper, and write the file to disk.

Here are those steps in code. First I look for local files:

//load code from any existing files in the folder

private Optional<List<Media>> getLocalCode() {

String directoryPath = appFolder;

File directory = new File(directoryPath);

if (!directory.exists()) {

System.out.println("Directory does not exist: " + directoryPath);

return Optional.empty();

}

try {

return Optional.of(Arrays.stream(directory.listFiles())

.filter(File::isFile)

.map(file -> {

try {

byte[] codeContent = Files.readAllLines(file.toPath())

.stream()

.collect(Collectors.joining("\n"))

.getBytes();

return new Media(MimeTypeUtils.TEXT_PLAIN, codeContent);

} catch (IOException e) {

System.out.println("Error reading file: " + file.getName());

return null;

}

})

.filter(Objects::nonNull)

.collect(Collectors.toList()));

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println("Error getting local code");

return Optional.empty();

}

}

I call the LLM using Spring AI, choosing one of two method depending on whether there’s any local code or not. There won’t be any code when the first prompt is executed!

//call the LLM and pass in existing code

private String callLlmWithLocalCode(String prompt, List<Media> localCode) {

System.out.println("calling LLM with local code");

var userMessage = new UserMessage(prompt, localCode);

var response = chatClient.call(new Prompt(List.of(userMessage)));

return extractCodeContent(response.toString());

}

//call the LLM when there's no local code

private String callLlmWithoutLocalCode(String prompt) {

System.out.println("calling LLM withOUT local code");

var response = chatClient.call(prompt);

return extractCodeContent(response.toString());

}

You see there that I’m extracting the code itself from the response string with this operation:

//method that extracts code from the LLM response

public static String extractCodeContent(String markdown) {

System.out.println("Markdown: " + markdown);

String regex = "`(\\w+)?\\n([\\s\\S]*?)```";

Pattern pattern = Pattern.compile(regex);

Matcher matcher = pattern.matcher(markdown);

if (matcher.find()) {

String codeContent = matcher.group(2); // Extract group 2 (code content)

return codeContent;

} else {

//System.out.println("No code fence found.");

return markdown;

}

}

And finally, I write the resulting code to disk:

//write the final code to the target file path

private void writeCodeToFile(String filePath, String codeContent) {

try {

File file = new File(filePath);

if (!file.exists()) {

file.createNewFile();

}

FileWriter writer = new FileWriter(file);

writer.write(codeContent);

writer.close();

System.out.println("Content written to file: " + filePath);

} catch (IOException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

There’s some more ancillary stuff that you can check out in the complete GitHub repo with this app in it. I was happy to be using Gemini Code Assist while building this. This AI assistant helped me understand some Java concepts, complete some functions, and fix some of my subpar coding choices.

That’s it. Once I had this component, I built a JAR file and could now use it locally or in a continuous integration pipeline to produce my code. I uploaded the JAR file to Google Cloud Storage so that I could use it later in my CI pipelines. Now, onto the day-to-day workflow that would use this generator!

Workflow step: Set up repo and pipeline

Like with most software projects, I’d start with the supporting machinery. In this case, I needed a source repo to hold the prompt JSON files. Done.

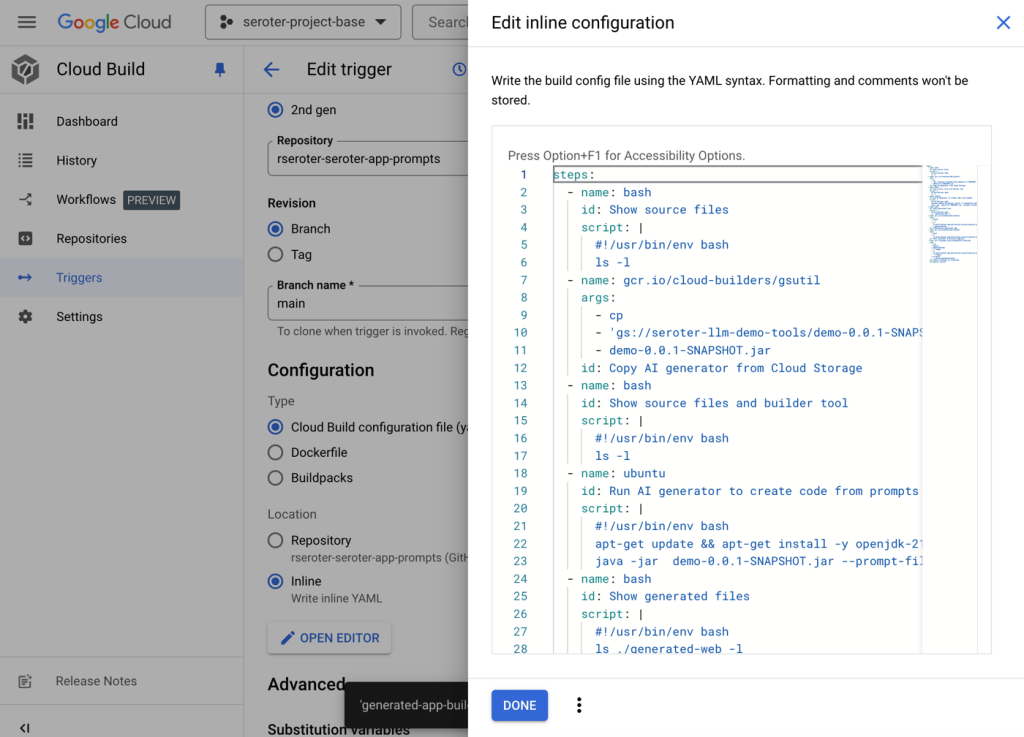

And I’d also consider setting up the path to production (or test environment, or whatever) to build the app as it takes shape. I’m using Google Cloud Build for a fully-managed CI service. It’s a good service with a free tier. Cloud Build uses declarative manifests for pipelines, and this pipeline starts off the same for any type of app.

steps:

# Print the contents of the current directory

- name: 'bash'

id: 'Show source files'

script: |

#!/usr/bin/env bash

ls -l

# Copy the JAR file from Cloud Storage

- name: 'gcr.io/cloud-builders/gsutil'

id: 'Copy AI generator from Cloud Storage'

args: ['cp', 'gs://seroter-llm-demo-tools/demo-0.0.1-SNAPSHOT.jar', 'demo-0.0.1-SNAPSHOT.jar']

# Print the contents of the current directory

- name: 'bash'

id: 'Show source files and builder tool'

script: |

#!/usr/bin/env bash

ls -l

Not much to it so far. I just print out the source contents seen in the pipeline, download the AI code generator from the above-mentioned Cloud Storage bucket, and prove that it’s on the scratch disk in Cloud Build.

Ok, my dev environment was ready.

Workflow step: Write prompts

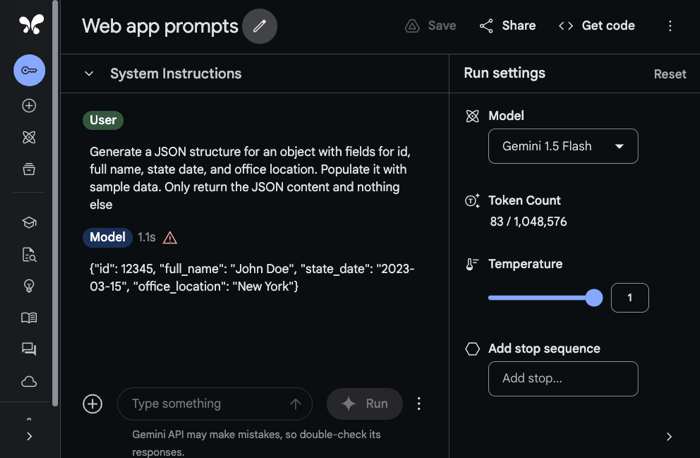

In this workflow, I don’t write code, I write prompts that generate code. I might use something like Google AI Studio or even Vertex AI to experiment with prompts and iterate until I like the response I get.

Within AI Studio, I chose Gemini 1.5 Flash because I like nice things. Here, I’d work through the various prompts I would need to generate a working app. This means I still need to understand programming languages, frameworks, Dockerfiles, etc. But I’m asking the LLM to do all the coding.

Once I’m happy with all my prompts, I add them to the JSON file. Note that each prompt entry has a corresponding file name that I want the generator to use when writing to disk.

At this point, I was done “coding” the Node.js app. You could imagine having a dozen or so templates of common app types and just grabbing one and customizing it quickly for what you need!

Workflow step: Test locally

To test this, I put the generator in a local folder with a prompt JSON file and ran this command from the shell:

rseroter$ java -jar demo-0.0.1-SNAPSHOT.jar --prompt-file=app-prompts-web.json

After just a few seconds, I had four files on disk.

This is just a regular Node.js app. After npm install and npm start commands, I ran the app and successfully pinged the exposed API endpoint.

Can we do things more sophisticated? I haven’t tried a ton of scenarios, but I wanted to see if I could get a database interaction generated successfully.

I went into the Google Cloud console and spun up a (free tier) instance of Cloud Firestore, our NoSQL database. I then created a “collection” called “Employees” and added a single document to start it off.

Then I built a new prompts file with directions to retrieve records from Firestore. I messed around with variations that encouraged the use of certain libraries and versions. Here’s a version that worked for me.

{

"folder": "generated-web-firestore",

"prompts": [

{

"fileName": "employee.json",

"prompt": "Generate a JSON structure for an object with fields for id, full name, state date, and office location. Populate it with sample data. Only return the JSON content and nothing else."

},

{

"fileName": "index.js",

"prompt": "Create a node.js program. Start up a web server on port 8080 and expose a route at /employee. Initializes a firestore database using objects from the @google-cloud/firestore package, referencing Google Cloud project 'seroter-project-base' and leveraging Application Default credentials. Return all the documents from the Employees collection."

},

{

"fileName": "package.json",

"prompt": "Create a valid package.json for this node.js application using version 7.7.0 for @google-cloud/firestore dependency. Do not include any comments in the JSON."

},

{

"fileName": "Dockerfile",

"prompt": "Create a Dockerfile for this node.js application that uses a minimal base image and exposes the app on port 8080."

}

]

}

After running the prompts through the generator app again, I got four new files, this time with code to interact with Firestore!

Another npm install and npm start command set started the app and served up the document sitting in Firestore. Very nice.

Finally, how about a Python app? I want a background job that actually populates the Firestore database with some initial records. I experimented with some prompts, and these gave me a Python app that I could use with Cloud Run Jobs.

{

"folder": "generated-job-firestore",

"prompts": [

{

"fileName": "main.py",

"prompt": "Create a Python app with a main function that initializes a firestore database object with project seroter-project-base and Application Default credentials. Add two documents to the Employees collection. Generate random id, fullname, startdate, and location data for each document. Have the start script try to call that main function and if there's an exception, prints the error."

},

{

"fileName": "requirements.txt",

"prompt": "Create a requirements.txt file for the packages used by this app"

},

{

"fileName": "Procfile",

"prompt": "Create a Procfile for python3 that starts up main.py"

},

{

"fileName": "Dockerfile",

"prompt": "Create a Dockerfile for this Python batch application that uses a minimal base image and doesn't expose any ports"

}

]

}

Running this prompt set through the AI generator gave me the valid files I wanted. All my prompt files are here.

At this stage, I was happy with the local tests and ready to automate the path from source control to cloud runtime.

Workflow step: Generate app in pipeline

Above, I had started the Cloud Build manifest with the step of yanking down the AI generator JAR file from Cloud Storage.

The next step is different for each app we’re building. I could use substitution variables in Cloud Build and have a single manifest for all of them, but for demonstration purposes, I wanted one manifest per prompt set.

I added this step to what I already had above. It executes the same command in Cloud Build that I had run locally to test the generator. First I do an apt-get on the “ubuntu” base image to get the Java command I need, and then invoke my JAR, passing in the name of the prompt file.

...

# Run the JAR file

- name: 'ubuntu'

id: 'Run AI generator to create code from prompts'

script: |

#!/usr/bin/env bash

apt-get update && apt-get install -y openjdk-21-jdk

java -jar demo-0.0.1-SNAPSHOT.jar --prompt-file=app-prompts-web.json

# Print the contents of the generated directory

- name: 'bash'

id: 'Show generated files'

script: |

#!/usr/bin/env bash

ls ./generated-web -l

I updated my Cloud Build pipeline that’s connected to my GitHub repo with an updated YAML manifest.

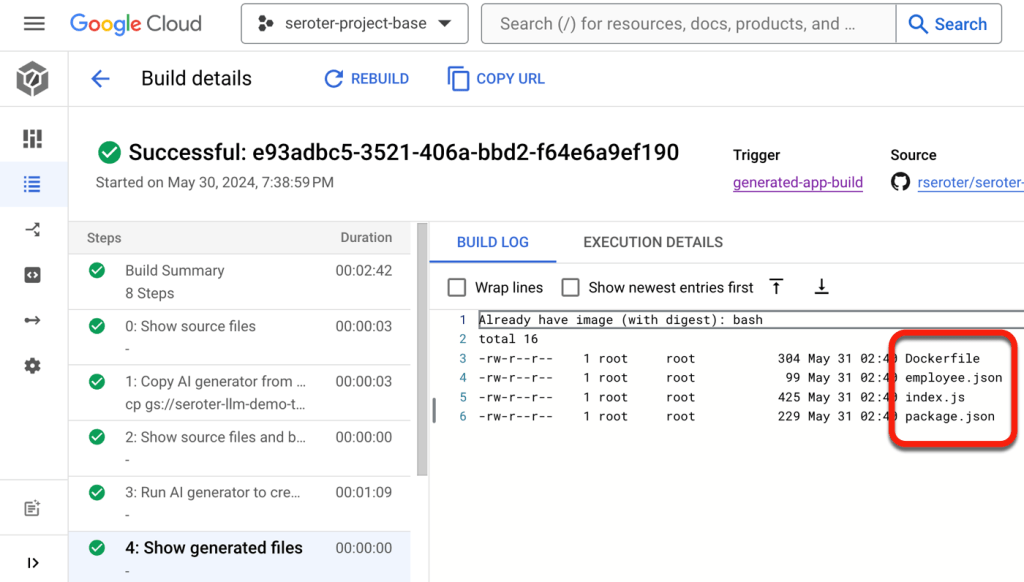

Running the pipeline at this point showed that the generator worked correctly and adds the expected files to the scratch volume in the pipeline. Awesome.

At this point, I had an app generated from prompts found in GitHub.

Workflow step: Upload artifact

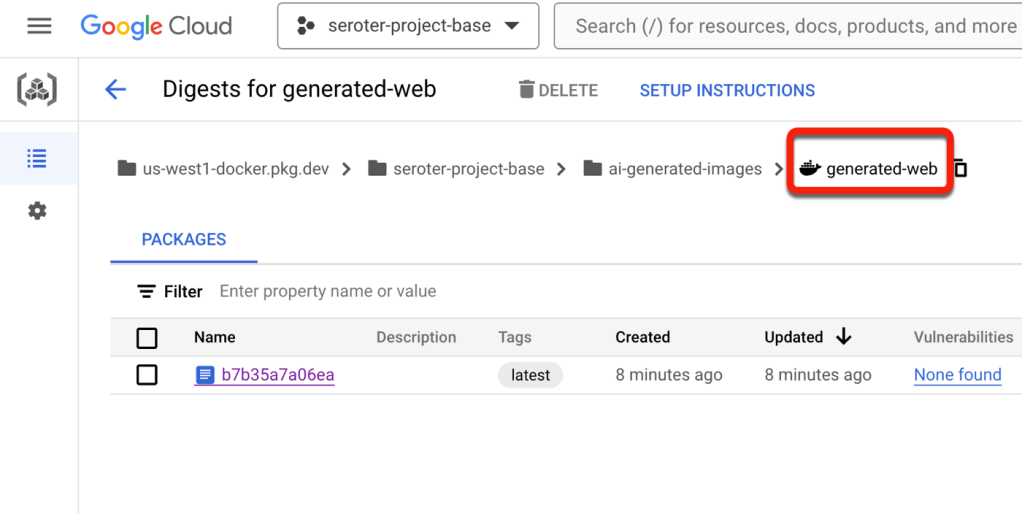

Next up? Getting this code into a deployable artifact. There are plenty of options, but I want to use a container-based runtime, and need a container image. Cloud Build makes that easy.

I added another section to my existing Cloud Build manifest to containerize with Docker and upload to Artifact Registry.

# Containerize the code and upload to Artifact Registry

- name: 'gcr.io/cloud-builders/docker'

id: 'Containerize generated code'

args: ['build', '-t', 'us-west1-docker.pkg.dev/seroter-project-base/ai-generated-images/generated-web:latest', './generated-web']

- name: 'gcr.io/cloud-builders/docker'

id: 'Push container to Artifact Registry'

args: ['push', 'us-west1-docker.pkg.dev/seroter-project-base/ai-generated-images/generated-web']

It used the Dockerfile our AI generator created, and after this step ran, I saw a new container image.

Workflow step: Deploy and run app

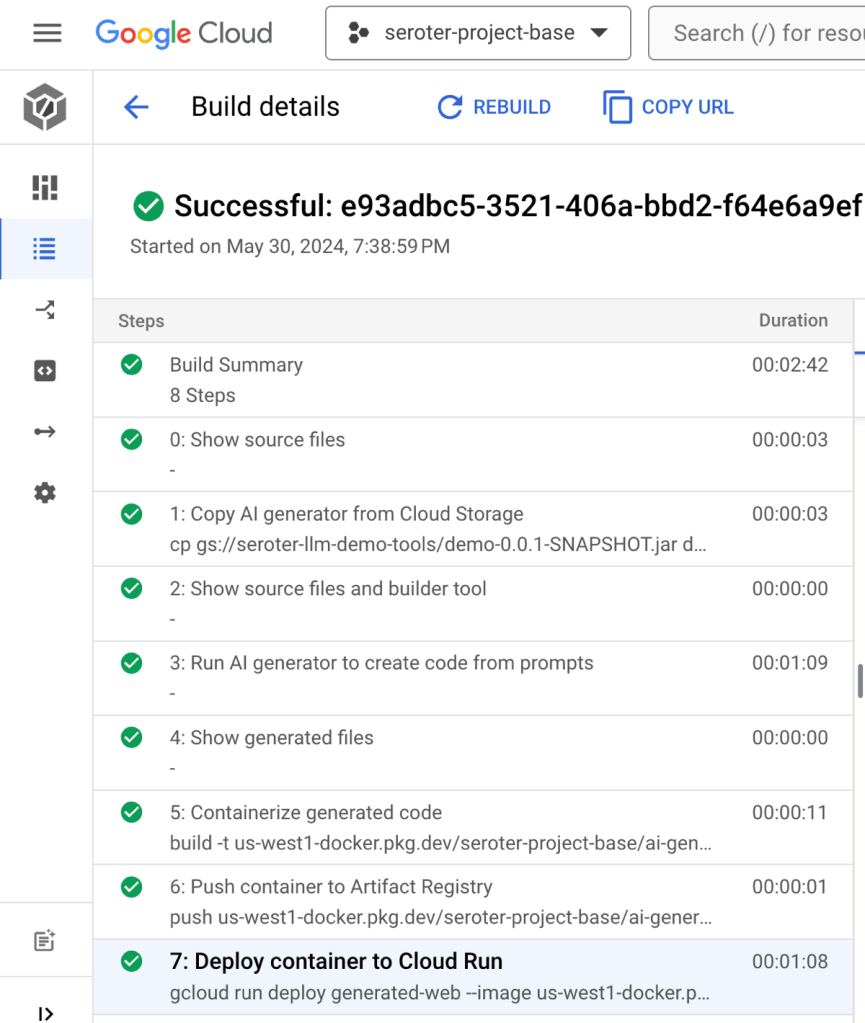

The final step, running the workload! I could use our continuous deployment service Cloud Deploy but I took a shortcut and deployed directly from Cloud Build. This step in the Cloud Build manifest does the job.

# Deploy container image to Cloud Run

- name: 'gcr.io/google.com/cloudsdktool/cloud-sdk'

id: 'Deploy container to Cloud Run'

entrypoint: gcloud

args: ['run', 'deploy', 'generated-web', '--image', 'us-west1-docker.pkg.dev/seroter-project-base/ai-generated-images/generated-web', '--region', 'us-west1', '--allow-unauthenticated']

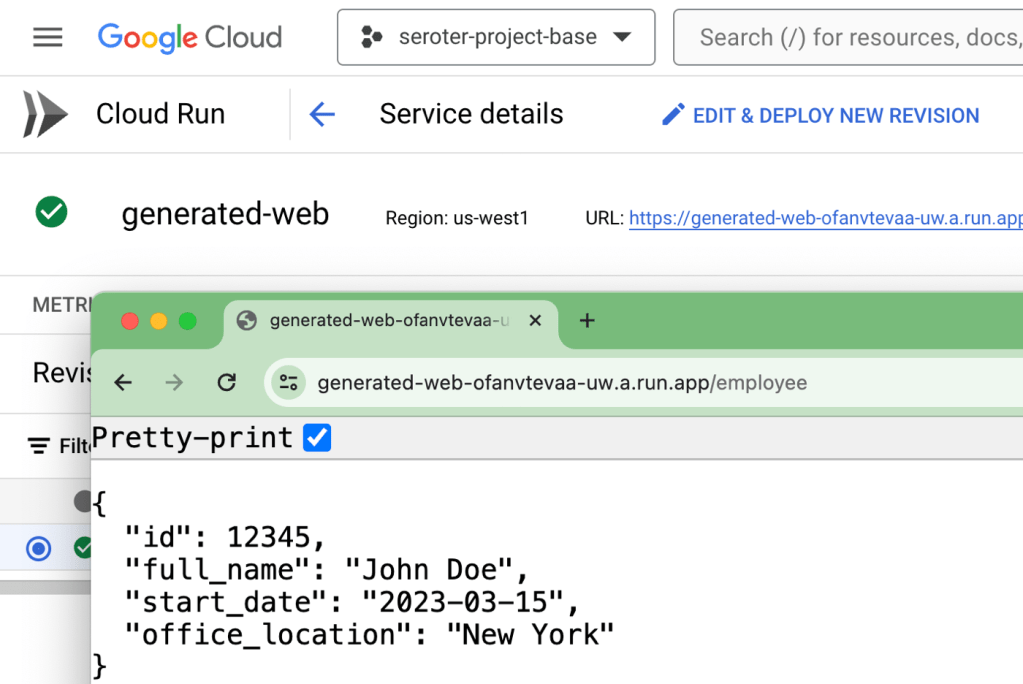

After saving this update to Cloud Build and running it again, I saw all the steps complete successfully.

Most importantly, I had an active service in Cloud Run that served up a default record from the API endpoint.

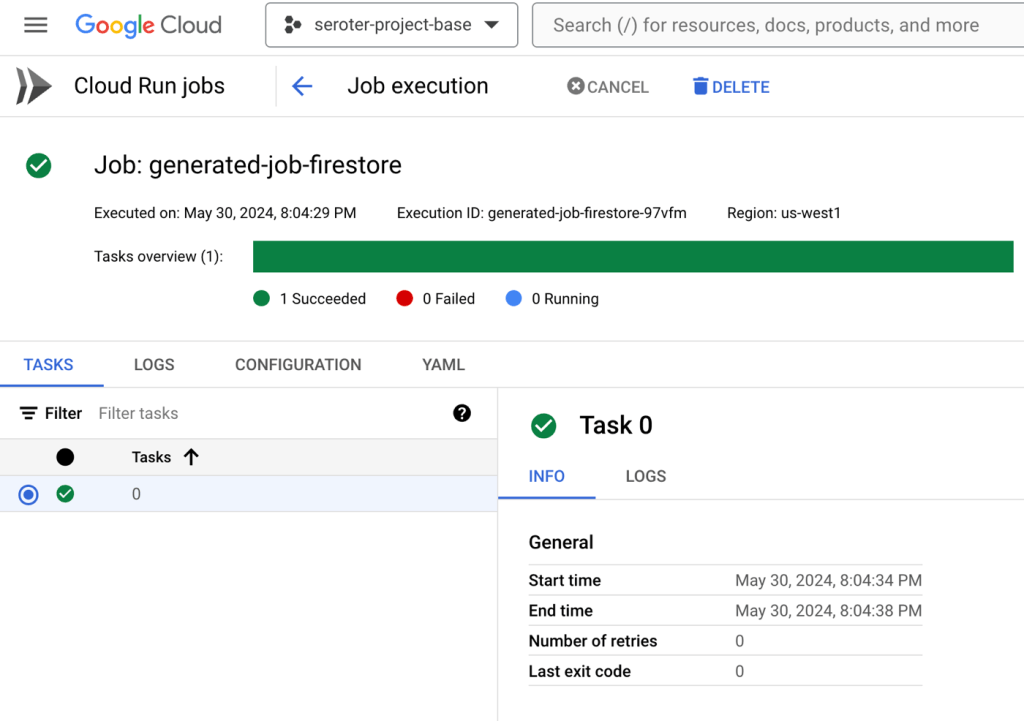

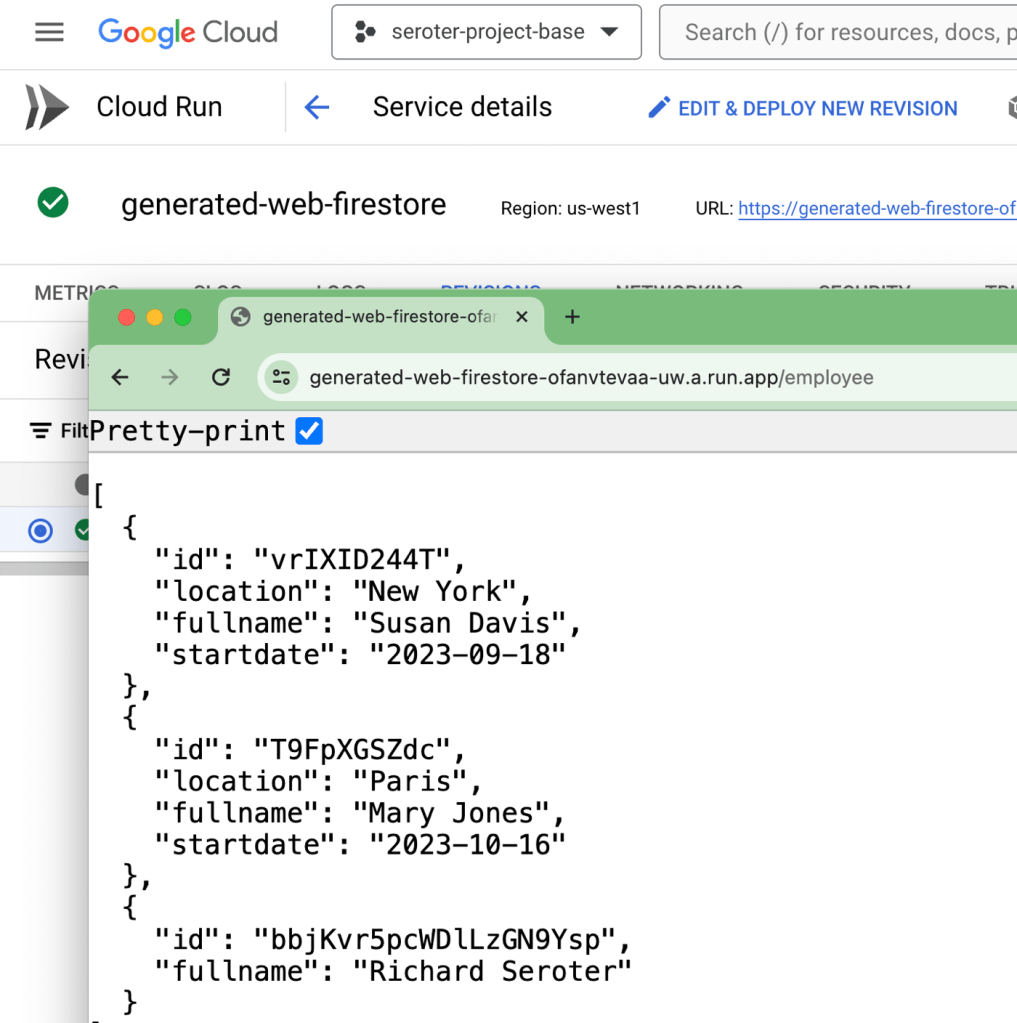

I went ahead and ran a Cloud Build pipeline for the “Firestore” version of the web app, and then the background job that deploys to Cloud Run Jobs. I ended up with two Cloud Run services (web apps), and one Cloud Run Job.

I executed the job, and saw two new Firestore records in the collection!

To prove that, I executed the Firestore version of the web app. Sure enough, the records returned include the two new records.

Wrap up

What we saw here was a fairly straightforward way to generate complete applications from nothing more than a series of prompts fed to the Gemini model. Nothing prevents you from using a different LLM, or using other source control, continuous integration, and hosting services. Just do some find-and-replace!

Again, I would NOT use this for “real” workloads, but this sort of pattern could be a powerful way to quickly create supporting apps and components for testing or learning purposes.

You can find the whole project here on GitHub.

What do you think? Completely terrible idea? Possibly useful?

Leave a reply to Prafull Cancel reply