I’ve got three kids now. Trying to get anywhere on time involves heroics. My son is almost ten years old and he’s rarely the problem. The bottleneck is elsewhere. It doesn’t matter how much faster my son gets himself ready, it won’t improve my family’s overall speed at getting out the door. The Theory of Constraints says that you improve the throughput of your process by finding and managing the bottleneck, or constraint. Optimizing areas outside the constraint (e.g. my son getting ready even faster) don’t make much of a difference. Does this relate to software, and application integration specifically? You betcha.

Software delivery goes through a pipeline. Getting from “idea” to “production” requires a series of steps. And then you repeat it over and over for each software update. How fast you get through that process dictates how responsive you can be to customers and business changes. Your development team may operate LIKE A MACHINE and crank out epic amounts of code. But if your dedicated ops team takes forever to deploy it, then it just doesn’t matter how fast your devs are. Inventory builds up, value is lost. My assertion is that the app integration stage of the pipeline is becoming a bottleneck. And without making changes to how you do integration, your cloud-native efforts are going to waste.

What’s “cloud native” all about? At this month’s Integrate conference, I had the pleasure of talking about it. Cloud-native refers to how software is delivered, not where. Cloud-native systems are built for scale, built for continuous change, and built to tolerate failure. Traditional enterprises can become cloud natives, but only if they make serious adjustments to how they deliver software.

Even if you’ve adjusted how you deliver code, I’d suspect that your data, security, and integration practices haven’t caught up. In my talk, I explained six characteristics of a cloud-native integration environment, and mixed in a few demos (highlighted below) to prove my points.

#1 – Cloud-native integration is more composable

By composable, I mean capable of assembling components into something greater. Contrast this to classic integration solutions where all the logic gets embedded into a single artifact. Think ETL workflows where ever step of the process is in one deployable piece. Need to change one component? Redeploy the whole thing. One step require a ton of CPU processing? Find a monster box to host the process in.

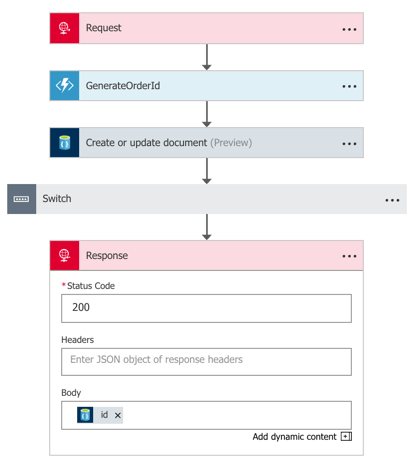

A cloud-native integration gets built by assembling independent components. Upgrade and scale each piece independently. To demonstrate this, I built a series of Microsoft Logic Apps. Two of them take in data. The first takes in a batch file from Microsoft OneDrive, the other takes in real-time HTTP requests. Both drop the results to a queue for later processing.

The “main” Logic App takes in order entries, enriches the order via a REST service I have running in Azure App Service, calls an Azure Function to assign a fraud score, and finally dumps the results to a queue for others to grab.

My REST API sitting in Azure App Service is connected to a GitHub repo. This means that I should be able to upgrade that individual service, without touching the data pipeline sitting Logic Apps. So that’s what I did. I sent in a steady stream of requests, modified my API code, pushed the change to GitHub, and within a few seconds, the Logic App is emitting out a slightly different payload.

#2 – Cloud-native integration is more “always on”

One of the best things about early cloud platforms being less than 100% reliable was that it forced us to build for failure. Instead of assuming the infrastructure was magically infallible, we built systems that ASSUMED failure, and architected accordingly.

For integration solutions, have we really done the same? Can we tolerate hardware failure, perform software upgrades, or absorb downstream dependency hiccups without stumbling? A cloud-native integration solution can handle a steady load of traffic while staying online under all circumstances.

#3 – Cloud-native integration is built for scale

Elasticity is a key attribute of cloud. Don’t build out infrastructure for peak usage; build for easy scale when demand dictates. I haven’t seen too many ESB or ETL solutions that transparently scale, on-demand with no special considerations. No, in most cases, scaling is a carefully designed part of an integration platform’s lifecycle. It shouldn’t be.

If you want cloud-native integration, you’ll look to solutions that support rapid scale (in, or out), and let you scale individual pieces. Event ingestions unexpected and overwhelming? Scale that, and that alone. You’ll also want to avoid too much shared capacity, as that creates unexpected coupling and makes scaling the environment more difficult.

#4 – Cloud-native integration is more self-service

The future is clear: there will be more “citizen integrators” who don’t need specialized training to connect stuff. IFTTT is popular, as are a whole new set of iPaaS products that make it simple to connect apps. Sure, they aren’t crazy sophisticated integrations; there will always be a need for specialists there. But integration matters more than ever, and we need to democratize the ability to connect our stuff.

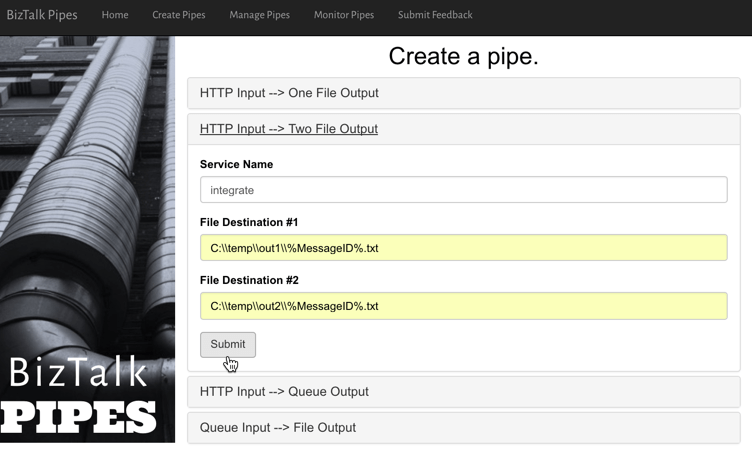

One example I gave here was Pivotal Cloud Cache and Pivotal GemFire. Pivotal GemFire is an industry-leading in-memory data grid. Awesome tech, but not trivial to properly setup and use. So, Pivotal created an opinionated slice of GemFire with a subset of features, but an easier on-ramp. Pivotal Cloud Cache supports specific use cases, and an easy self-service provisioning experience. My challenge to the Integrate conference audience? Why couldn’t we create a simple facade for something powerful, but intimidating, like Microsoft BizTalk Server? What if you wanted a self-service way to let devs create simple integrations? I decided use the brand new Management REST API from BizTalk Server 2016 Feature Pack 1 to build one.

I used the incomparable Spring Boot to build a Java app that consumed those REST APIs. This app makes it simple to create a “pipe” that uses BizTalk’s durable bus to link endpoints.

I built a bunch of Java classes to represent BizTalk objects, and then created the required API payloads.

The result? Devs can create a new pipe that takes in data via HTTP and drops the result to two file locations.

When I click the button above, I use those REST APIs to create a new in-process HTTP receive location, two send ports, and the appropriate subscriptions.

Fun stuff. This seems like one way you could unlock new value in your ESB, while giving it a more cloud-native UX.

#5 – Cloud-native integration supports more endpoints

There’s no turning back. Your hippest integration offered to enterprise devs CANNOT be SharePoint. Nope. Your teams want to creatively connect to Slack, PagerDuty, Salesforce, Workday, Jira, and yes, enterprisey things like SQL Server and IBM DB2.

These endpoints may be punishing your integration platform with a constant data stream, or, process data irregularly, in bulk. Doing newish patterns like Event Sourcing? Your apps will talk to an integration platform that offers a distributed commit log. Are you ready? Be ready for new endpoints, with new data streams, consumed via new patterns.

#6 – Cloud-native integration demands complete automation

Are you lovingly creating hand-crafted production servers? Stop that. And devs should have complete replicas of production environments, on their desktop. That means packaging and automating the integration bus too. Cloud-natives love automation!

Testing and deploying integration apps must be automated. Without automated tests, you’ll never achieve continuous delivery of your whole system. Additionally, if you have to log into one of your integration servers, you’re doing it wrong. All management (e.g. monitoring, deployments, upgrades) should be done via remote tools and scripts. Think fleets of servers, not long-lived named instances.

To demonstrate this concept, I discussed automating the lifecycle of your integration dependency. Specifically, through the use of a service broker. Initially part of Cloud Foundry, the service broker API has caught on elsewhere. A broad set of companies are now rallying around a single API for advertising services, provisioning, de-provisioning, and more. Microsoft built a Cloud Foundry service broker, and it handles lots of good things. It handles lifecycle and credential sharing for services like Azure SQL Database, Azure Service Bus, Azure CosmosDB, and more. I installed this broker into my Pivotal Web Services account, and it advertised available services.

Simply by typing in cf create-service azure-servicebus standard integratesb -c service-bus-config.json I kicked off a fast, automated process to generate an Azure Resource Group and create a Service Bus namespace.

Then, my app automatically gets access to environment variables that hold the credentials. No more embedding creds in code or config, no need to go to the Azure Portal. This makes integration easy, developer-friendly, and repeatable.

Summary

It’s such an exciting time to be a software developer. We’re solving new problems in new ways, and making life better for so many. The last thing we want is to be held back by a bottleneck in our process. Don’t let integration slow down your ambitions. The technology is there to help you build integration platforms that are more scalable, resilient, and friendly-to-change. Go for it!