What exactly is a “generative AI app”? Do you think of chatbots, image creation tools, or music makers? What about document analysis services, text summarization capabilities, or widgets that “fix” your writing? These all seem to apply in one way or another! I see a lot written about tools and techniques for training, fine-tuning, and serving models, but what about us app builders? How do we actually build generative AI apps without obsessing over the models? Here’s what I’d consider using in 2024. And note that there’s much more to cover besides just building—think designing, testing, deploying, operating—but I’m just focusing on the builder tools today.

Find a sandbox for experimenting with prompts

A successful generative AI app depends on a useful model, good data, and quality prompts. Before going to deep on the app itself, it’s good to have a sandbox to play in.

You can definitely start with chat tools like Gemini and ChatGPT. That’s not a bad way to get your hands dirty. There’s also a set of developer-centric surfaces such as Google Colab or Google AI Studio. Once you sign in with a Google ID, you get free access to environments to experiment.

Let’s look at Google AI Studio. Once you’re in this UI, you have the ability to simulate a back-and-forth chat, create freeform prompts that include uploaded media, or even structured prompts for more complex interactions.

If you find yourself staring at an empty console wondering what to try, check out this prompt gallery that shows off a lot of unique scenarios.

Once you’re doing more “serious” work, you might upgrade to a proper cloud service that offers a sandbox along with SLAs and prompt lifecycle capabilities. Google Cloud Vertex AI is one example. Here, I created a named prompt.

With my language prompts, I can also jump into a nice “compare” experience where I can try out variations of my prompt and see if the results are graded as better or worse. I can even set one as “ground truth” used as a baseline for all comparisons.

Whatever sandbox tools you use, make sure they help you iterate quickly, while also matching the enterprise-y needs of the use case or company you work for.

Consume native APIs when working with specific models or platforms

At this point, you might be ready to start building your generative AI app. There seems to be a new, interesting foundation model up on Hugging Face every couple of days. You might have a lot of affection for a specific model family, or not. If you care about the model, you might choose the APIs for that specific model or provider.

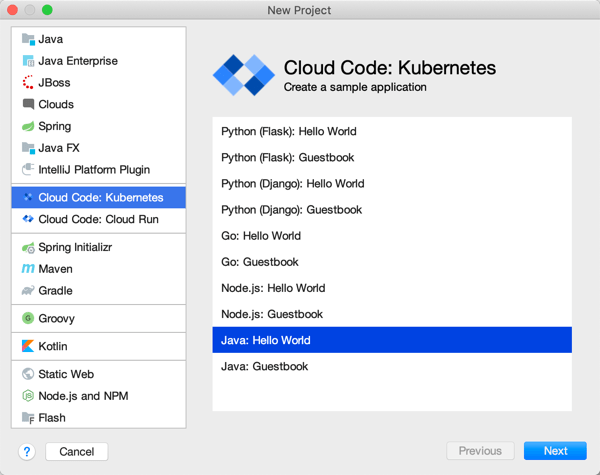

For example, let’s say you were making good choices and anchored your app to the Gemini model. I’d go straight to the Vertex AI SDK for Python, Node, Java, or Go. I might even jump to the raw REST API and build my app with that.

If I were baking a chat-like API call into my Node.js app, the quickest way to get the code I need is to go into Vertex AI, create a sample prompt, and click the “get code” button.

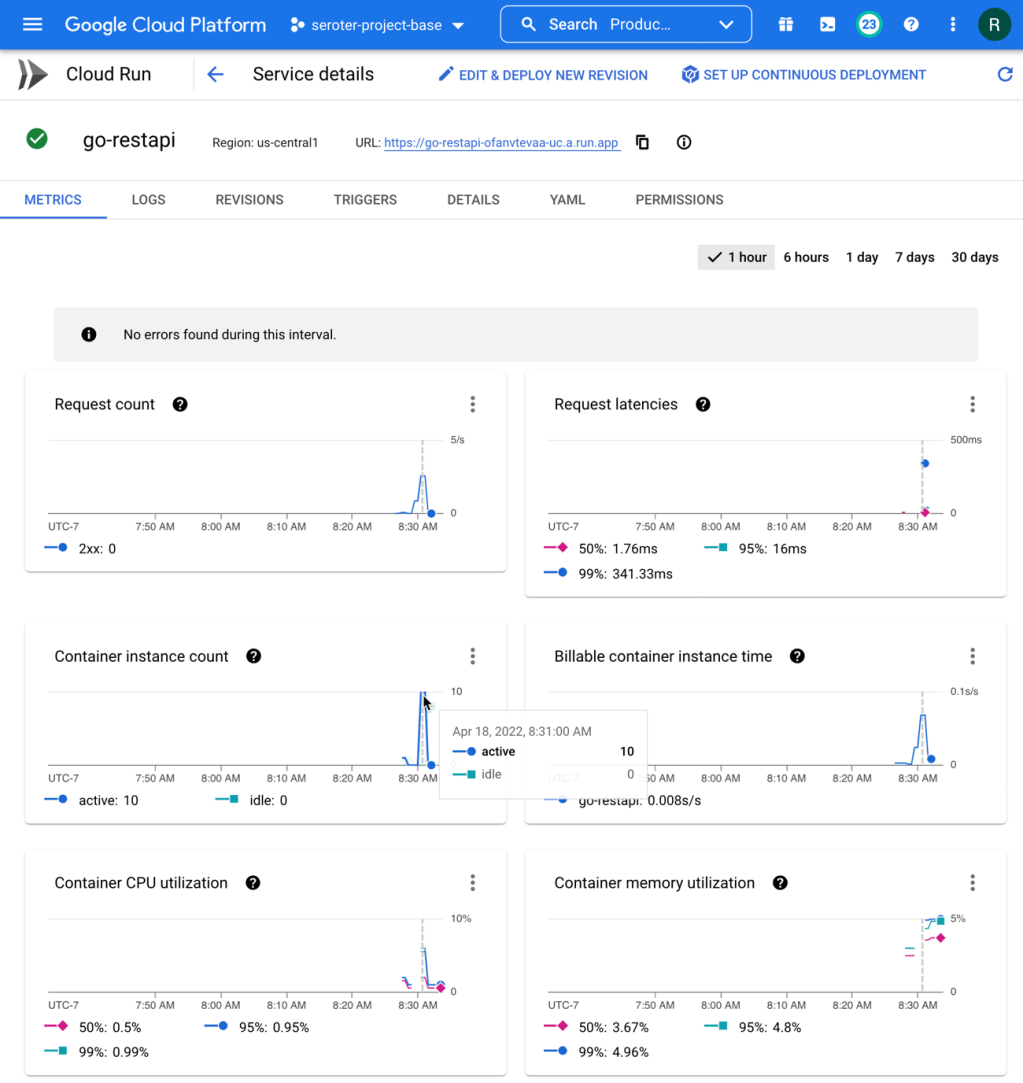

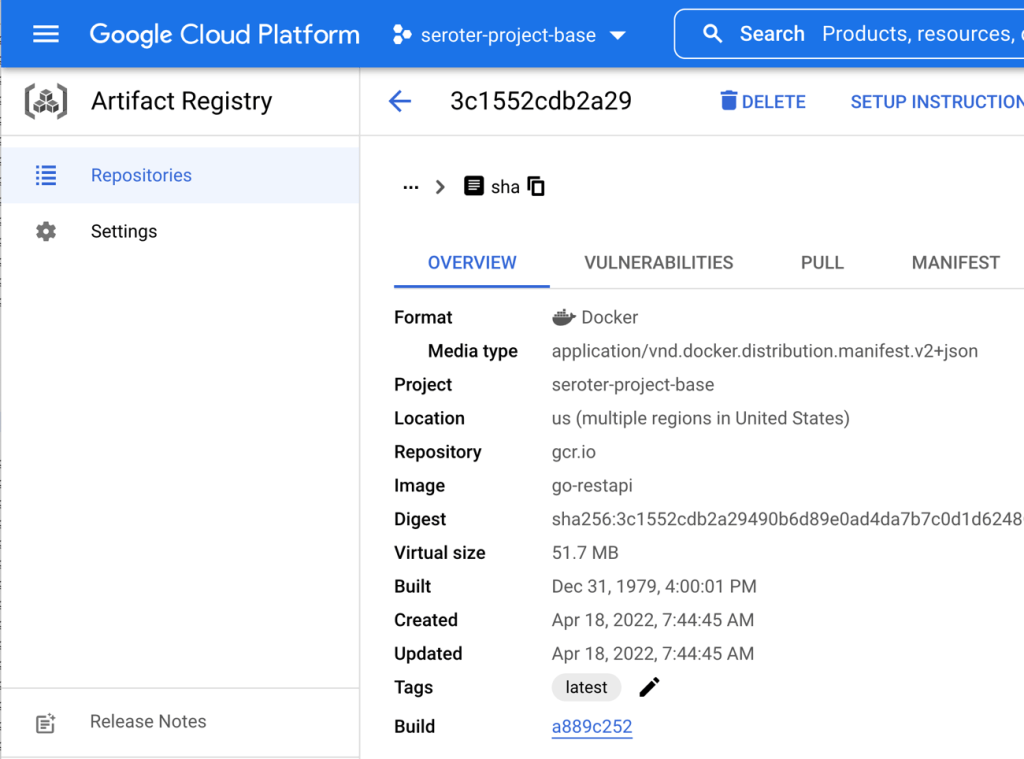

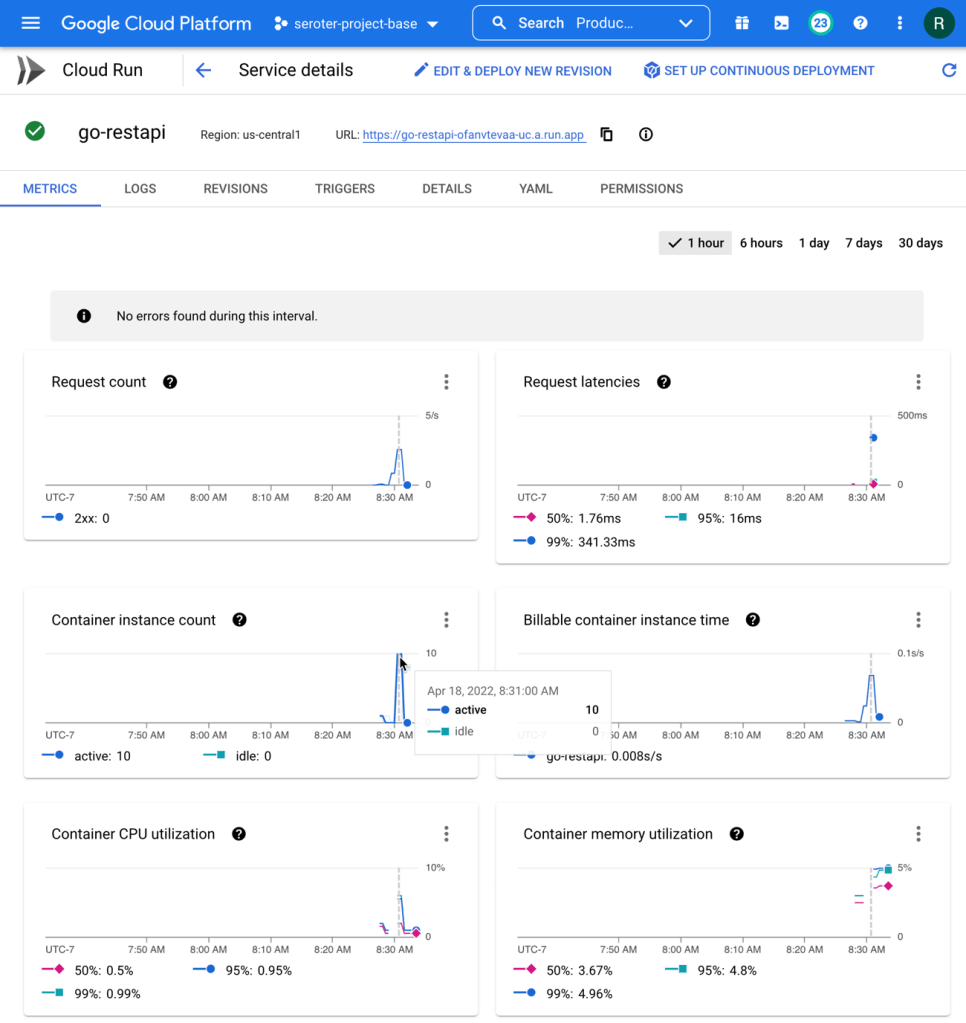

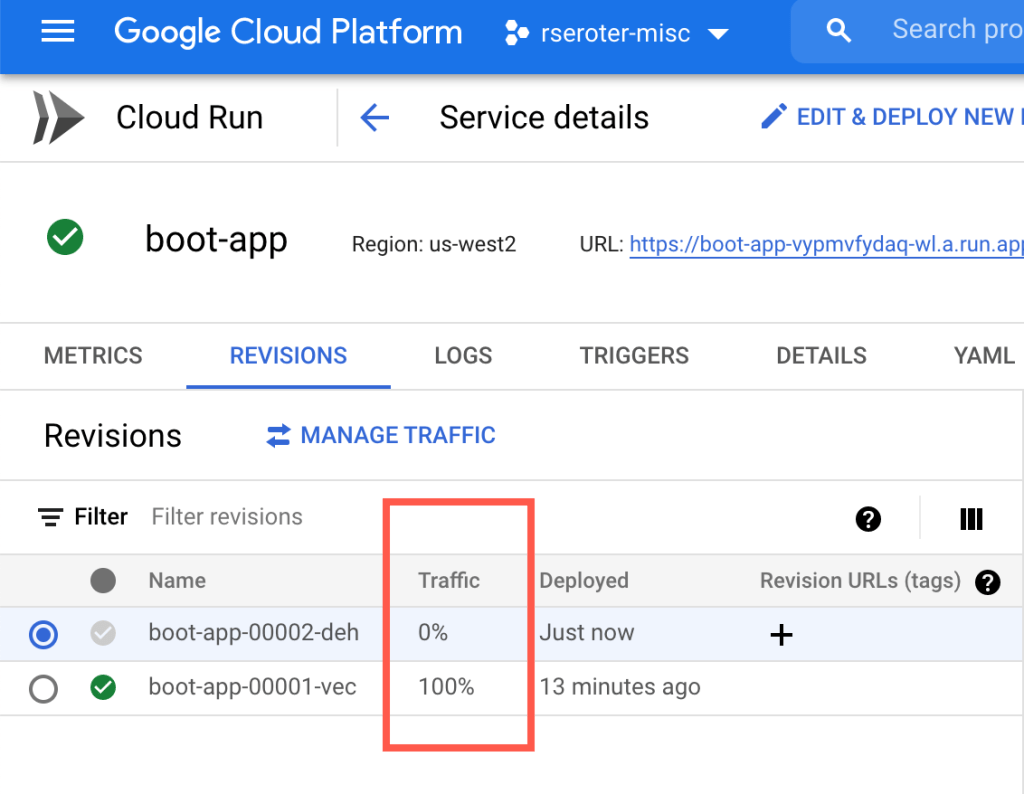

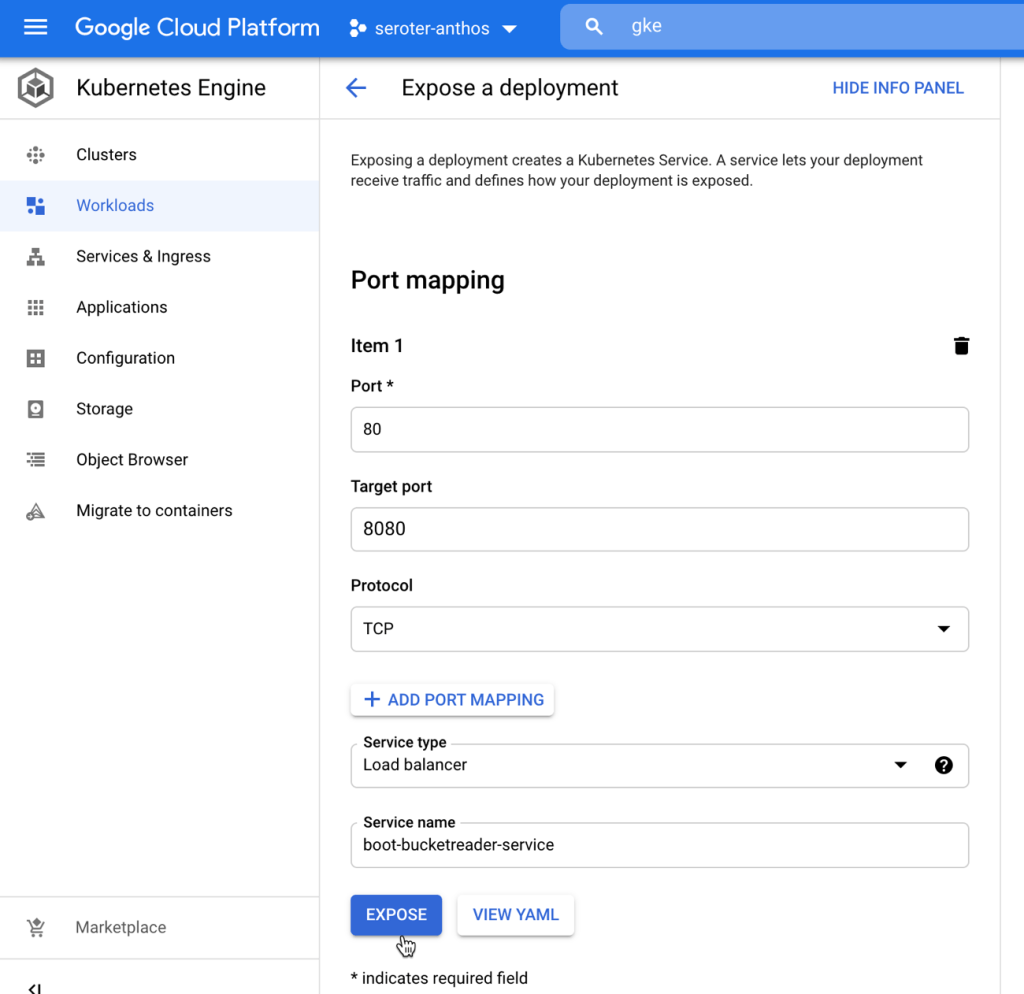

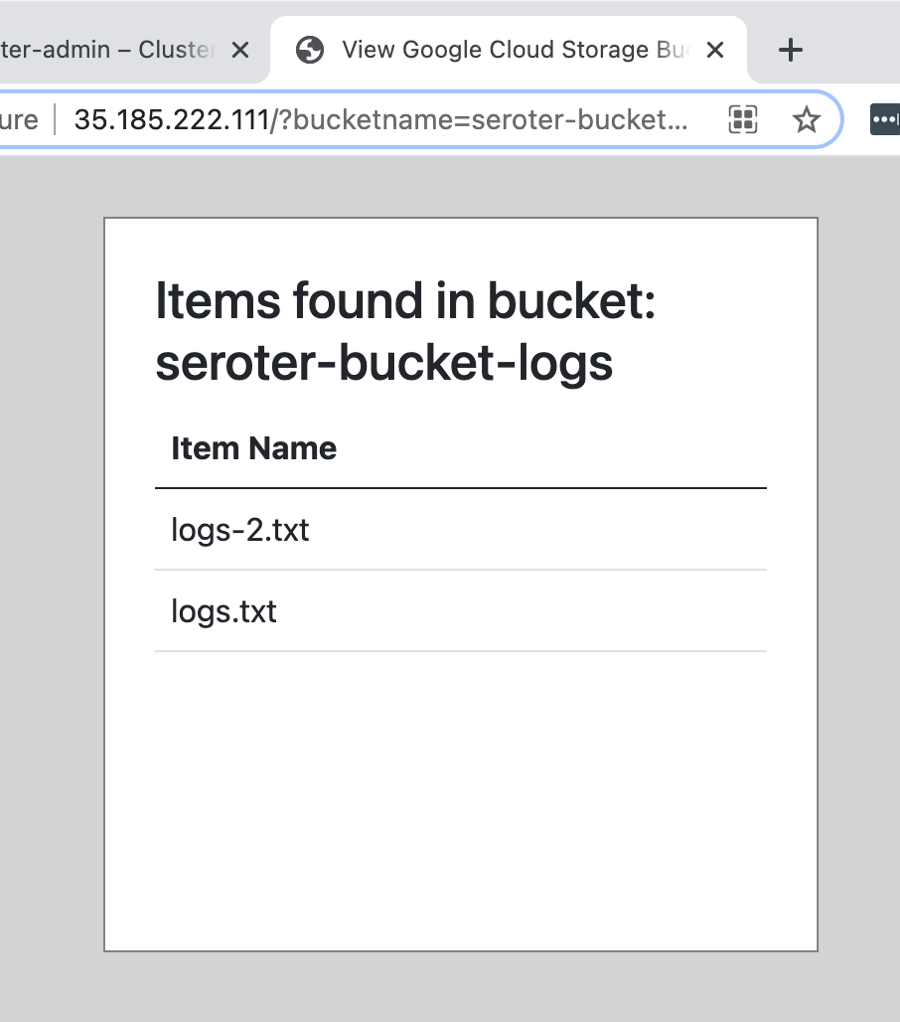

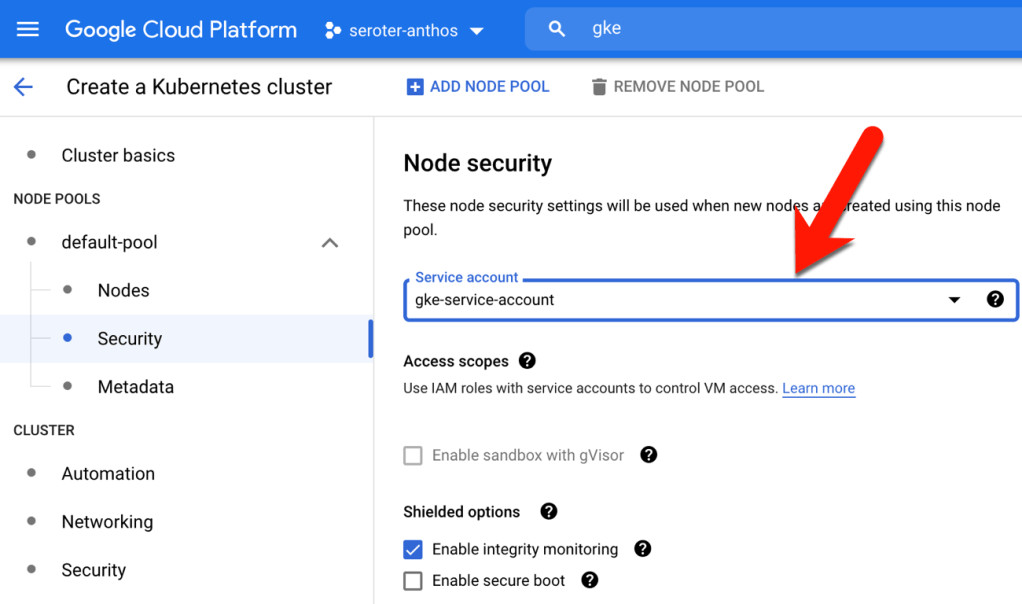

I took that code, ran it in a Cloud Shell instance, and it worked perfectly. I could easily tweak it for my specific needs from here. Drop this code into a serverless function, Kubernetes pod, or VM and you’ve got a working generative AI app.

You could follow this same direct API approach when building out more sophisticated retrieval augmented generation (RAG) apps. In a Google Cloud world, you might use the Vertex AI APIs to get text embeddings. Or you could choose something more general purpose and interact with a PostgreSQL database to generate, store, and query embeddings. This is an excellent example of this approach.

If you have a specific model preference, you might choose to use the API for Gemini, Llama, Mistral, or whatever. And you might choose to directly interact with database or function APIs to augment the input to those models. That’s cool, and is the right choice for many scenarios.

Use meta-frameworks for consistent experiences across models and providers

As expected, the AI builder space is now full of higher-order frameworks that help developers incorporate generative AI into their apps. These frameworks help you call LLMs, work with embeddings and vector databases, and even support actions like function calling.

LangChain is a big one. You don’t need to be bothered with many model details, and you can chain together tasks to get results. It’s for Python devs, so your choice is either to use Python, or, embrace one of the many offshoots. There’s LangChain4J for Java devs, LangChain Go for Go devs, and LangChain.js for JavaScript devs.

You have other choices if LangChain-style frameworks aren’t your jam. There’s Spring AI, which has a fairly straightforward set of objects and methods for interacting with models. I tried it out for interacting with the Gemini model, and almost found it easier to use than our native API! It takes one update to my POM file:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.ai</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-ai-vertex-ai-gemini-spring-boot-starter</artifactId>

</dependency>

One set of application properties:

spring.application.name=demo

spring.ai.vertex.ai.gemini.projectId=seroter-dev

spring.ai.vertex.ai.gemini.location=us-central1

spring.ai.vertex.ai.gemini.chat.options.model=gemini-pro-vision

And then an autowired chat object that I call from anywhere, like in this REST endpoint.

@RestController

@SpringBootApplication

public class DemoApplication {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(DemoApplication.class, args);

}

private final VertexAiGeminiChatClient chatClient;

@Autowired

public DemoApplication(VertexAiGeminiChatClient chatClient) {

this.chatClient = chatClient;

}

@GetMapping("/")

public String getGeneratedText() {

String generatedResponse = chatClient.call("Tell me a joke");

return generatedResponse;

}

}

Super easy. There are other frameworks too. Use something like AI.JSX for building JavaScript apps and components. BotSharp is a framework for .NET devs building conversational apps with LLMs. Hugging Face has frameworks that help you abstract the LLM, including Transformers.js and agents.js.

There’s no shortage of these types of frameworks. If you’re iterating through LLMs and want consistent code regardless of which model you use, these are good choices.

Create with low-code tools when available

If I had an idea for a generative AI app, I’d want to figure out how much I actually had to build myself. There are a LOT of tools for building entire apps, components, or widgets, and many require very little coding.

Everyone’s in this game. Zapier has some cool integration flows. Gradio lets you expose models and APIs as web pages. Langflow got snapped up by DataStax, but still offers a way to create AI apps without much required coding. Flowise offers some nice tooling for orchestration or AI agents. Microsoft’s Power Platform is useful for low-code AI app builders. AWS is in the game now with Amazon Bedrock Agents. ServiceNow is baking generative AI into their builder tools, Salesforce is doing their thing, and basically every traditional low-code app vendor is playing along. See OutSystems, Mendix, and everyone else.

As you would imagine, Google does a fair bit here as well. The Vertex AI Agent Builder offers four different app types that you basically build through point-and-click. These include personalized search engines, chat, recommendation engine, and connected agents.

Search apps can tap into a variety of data sources including crawled websites, data warehouses, relational databases, and more.

What’s fairly new is the “agent app” so let’s try building one of those. Specifically, let’s say I run a baseball clinic (sigh, someday) and help people tune their swing in our batting cages. I might want a chat experience for those looking for help with swing mechanics, and then also offer the ability to book time in the batting cage. I need data, but also interactivity.

Before building the AI app, I need a Cloud Function that returns available times for the batting cage.

This Node.js function returns an array of book-able timeslots. I’ve hard-coded the data, but you get the idea.

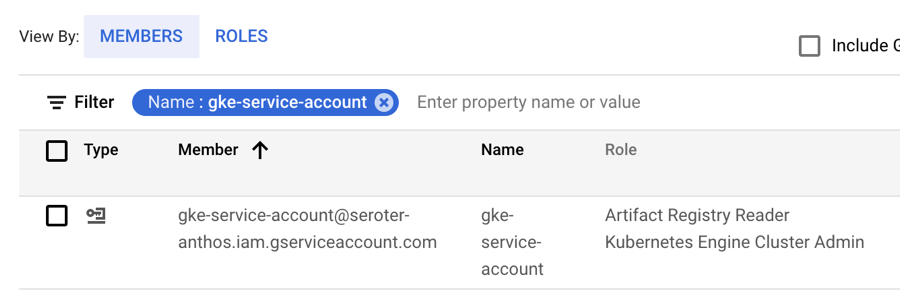

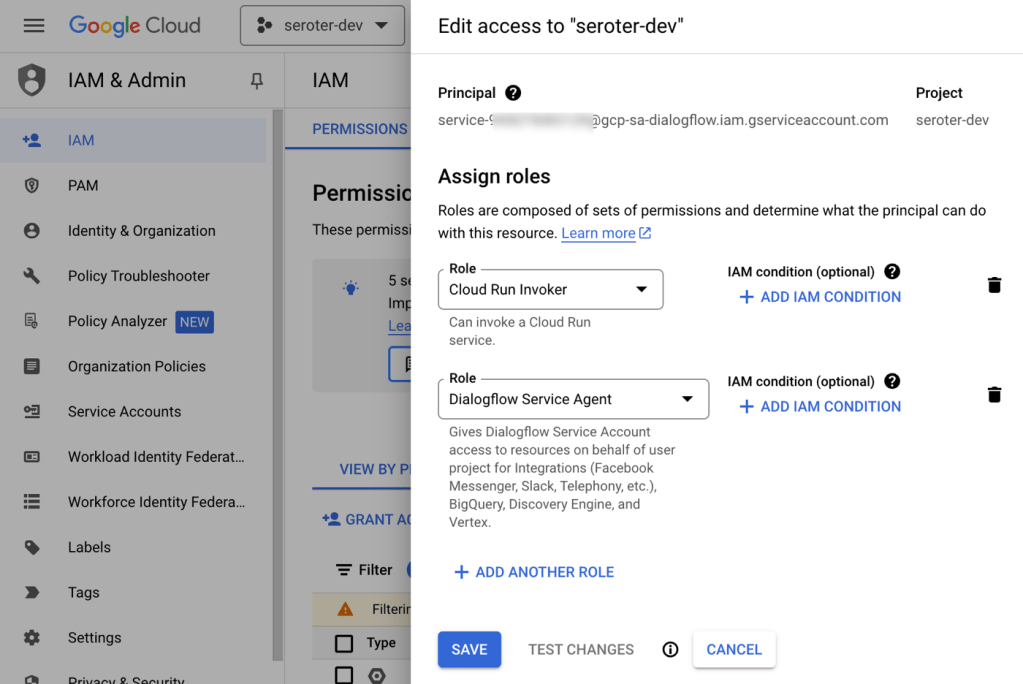

I also jumped into the Google Cloud IAM interface to ensure that the Dialogflow service account (which the AI agent operates as) has permission to invoke the serverless function.

Let’s build the agent. Back in the Vertex AI Agent Builder interface, I choose “new app” and pick “agent.”

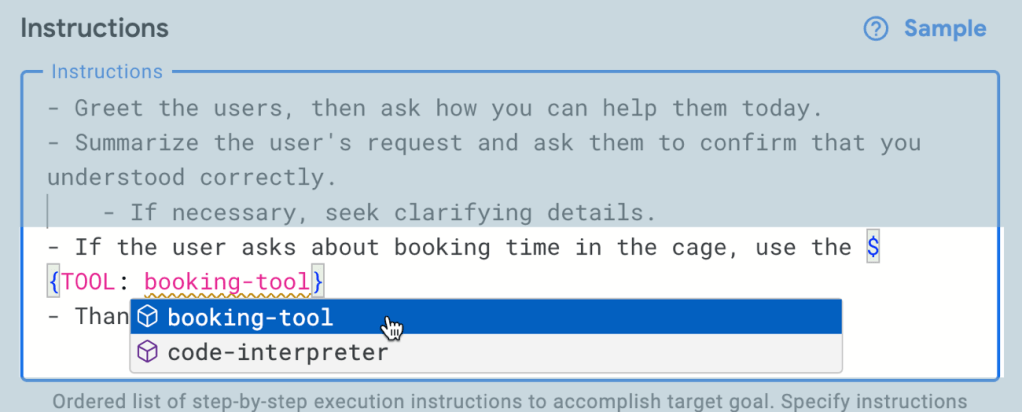

Now I’m dropped into the agent builder interface. On the left, I have navigation for agents, tools, test cases, and more. In the next column, I set the goal of the agent, the instructions, and any tools I want to use with the agent. On the right, I preview my agent.

I set a goal of “Answer questions about baseball and let people book time in the batting cage” and then get to the instructions. There’s a “sample” set of instructions that are useful for getting started. I used those, but removed references to other agents or tools, as we don’t have that yet.

But now I want to add a tool, as I need a way to show available booking times if the user asks. I have a choice of adding a data store—this is useful if you want to source Q&A from a BigQuery table, crawl a website, or get data from an API. I clicked the “manage all tools” button and chose to add a new tool. Here I give the tool a name, and very importantly, a description. This description is used by the AI agent to figure out when to invoke it.

Because I chose OpenAPI as the tool type, I need to provide an OpenAPI spec for my Cloud Function. There’s a sample provided, and I used that to put together my spec. Note that the URL is the function’s base URL, and the path contains the specific function name.

{

"openapi": "3.0.0",

"info": {

"title": "Cage API",

"version": "1.0.0"

},

"servers": [

{

"url": "https://us-central1-seroter-anthos.cloudfunctions.net"

}

],

"paths": {

"/function-get-cage-times": {

"get": {

"summary": "List all open cage times",

"operationId": "getCageTimes",

"responses": {

"200": {

"description": "An array of cage times",

"content": {

"application/json": {

"schema": {

"type": "array",

"items": {

"$ref": "#/components/schemas/CageTimes"

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

},

"components": {

"schemas": {

"CageTimes": {

"type": "object",

"required": [

"cageNumber",

"openSlot",

"cageType"

],

"properties": {

"cageNumber": {

"type": "integer",

"format": "int64"

},

"openSlot": {

"type": "string"

},

"cageType": {

"type": "string"

}

}

}

}

}

}

Finally, in this “tool setup” I define the authentication to that API. I chose “service agent token” and because I’m calling a specific instance of a service (versus the platform APIs), I picked “ID token.”

After saving the tool, I go back to the agent definition and want to update the instructions to invoke the tool. I use the syntax, and appreciated the auto-completion help.

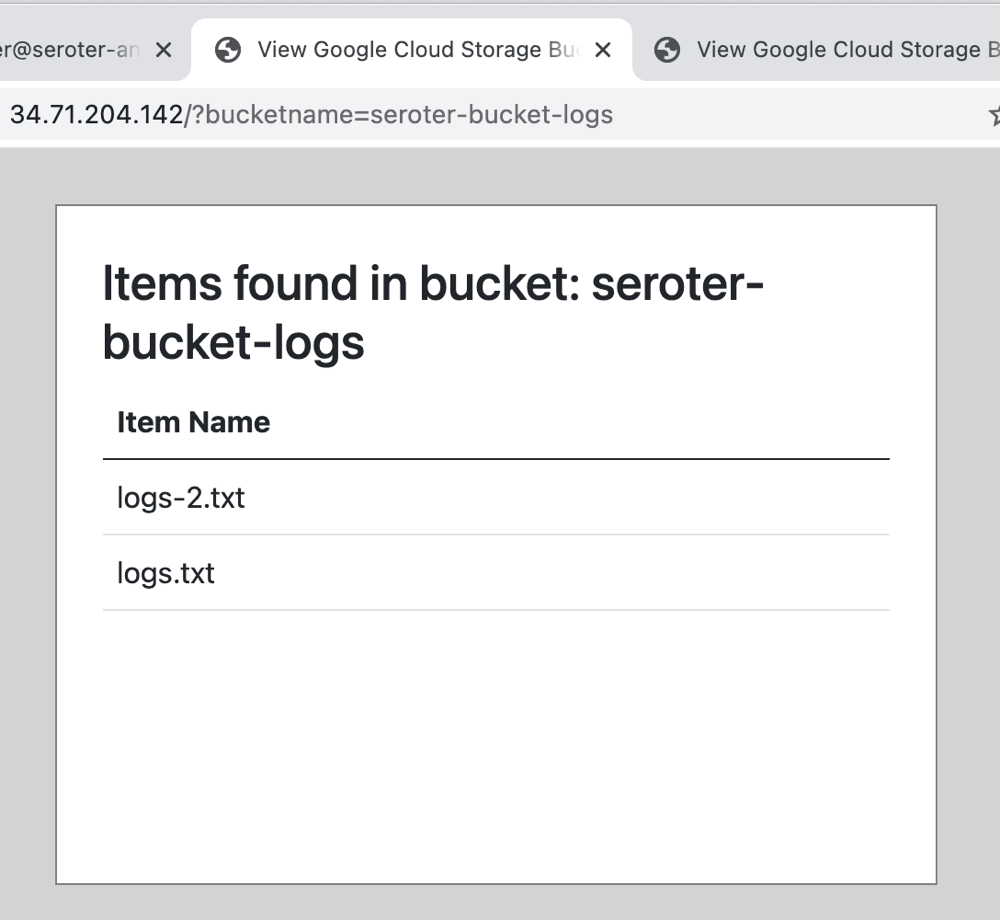

Let’s see if it works. I went to the right-hand preview pane and asked it a generic baseball question. Good. Then I asked it for open times in the batting cage. Look at that! It didn’t just return a blob of JSON; it parsed the result and worded it well.

Very cool. There are some quirks with this tool, but it’s early, and I like where it’s going. This was MUCH simpler than me building a RAG-style or function-calling solution by hand.

Summary

The AI assistance and model building products get a lot of attention, but some of the most interesting work is happening in the tools for AI app builders. Whether you’re experimenting with prompts, coding up a solution, or assembling an app out of pre-built components, it’s a fun time to be developer. What products, tools, or frameworks did I miss from my assessment?