So far in this series of posts, we’ve seen that Pivotal Cloud Foundry (PCF) runs a lot more than just web applications. Not every app has a user-facing front-end component. Some of your systems run in the background or on a schedule and perform a variety of important tasks. In this post, I’ll take a look at how to deploy background workers, on-demand batch tasks, and scheduled jobs.

This is the third in a five part series of posts:

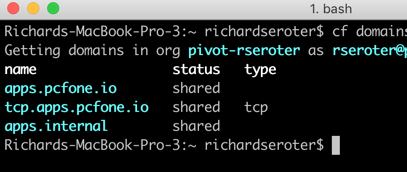

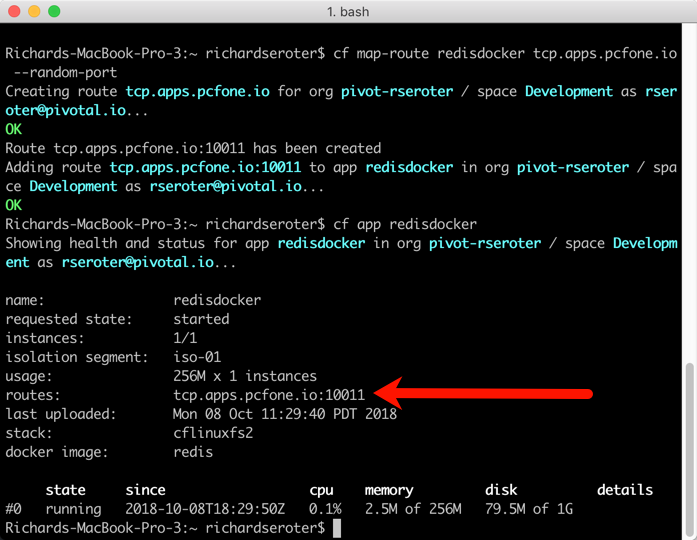

- Part 1 – Deploying and running Docker images

- Part 2 – Setting up TCP routable services

- Part 3 – Running batch and scheduled jobs

- Part 4 – Configuring data streaming apps

- Part 5 – Deploying .NET Framework apps to Windows Server

Deploying and running background workers

Pivotal Cloud Foundry makes it easy to run workers that don’t have a routable address. These background jobs might listen to a database and respond to data changes, or respond to messages in a work queue. Let’s demonstrate the latter.

I built a .NET Core console app that’s responsible for pulling “loan” records from RabbitMQ and processing them. You can built these background jobs is any programming language supported by Cloud Foundry.

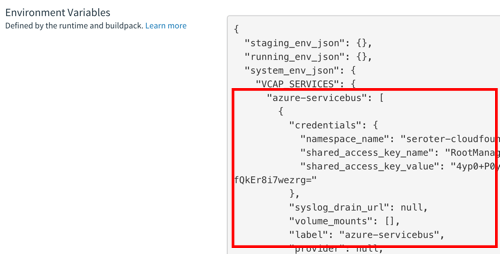

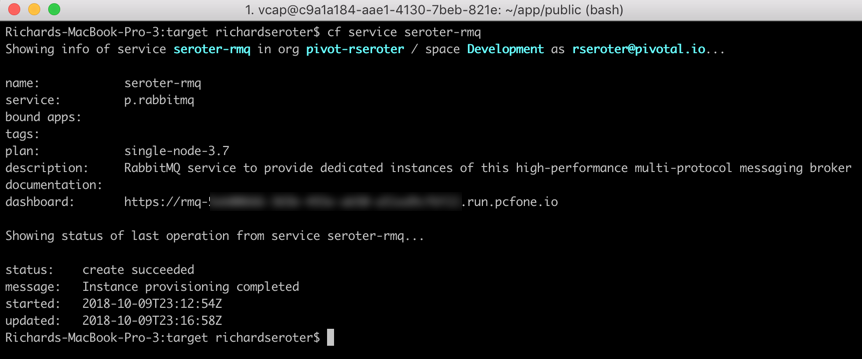

What’s nice is that background jobs have access to all the useful PCF capabilities that web apps do. One such capability? Service Brokers! Devs love using Service Brokers to provision and access backing services. My background job needs access to RabbitMQ and I don’t want to hard-code any connection details. No big deal. I first spun up an on-demand RabbitMQ instance via the PCF Service Broker.

My .NET Core app uses the Steeltoe Service Connector (and the RabbitMQ .NET Client) to load service broker connection info and talk to my instance.

static void Main(string[] args){

//pull service broker configuration

var builder = new ConfigurationBuilder()

.AddEnvironmentVariables()

.AddCloudFoundry();

var configuration = builder.Build();

//get our fully loaded service

var services = new ServiceCollection();

services.AddRabbitMQConnection(configuration);

var provider = services.BuildServiceProvider();

ConnectionFactory f = provider.GetService<ConnectionFactory>();

//connect to RMQ

using (var connection = f.CreateConnection())

using (var channel = connection.CreateModel())

{

channel.QueueDeclare(queue: "loans", durable: true, exclusive: false, autoDelete: false, arguments: null);

var consumer = new EventingBasicConsumer(channel);

//fire up when a new message comes in

consumer.Received += (model, ea) => {

var body = ea.Body;

var message = Encoding.UTF8.GetString(body);

Console.WriteLine("[x] Received loan data: {0}", message);

};

channel.BasicConsume(queue: "loans", autoAck: true, consumer: consumer);

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

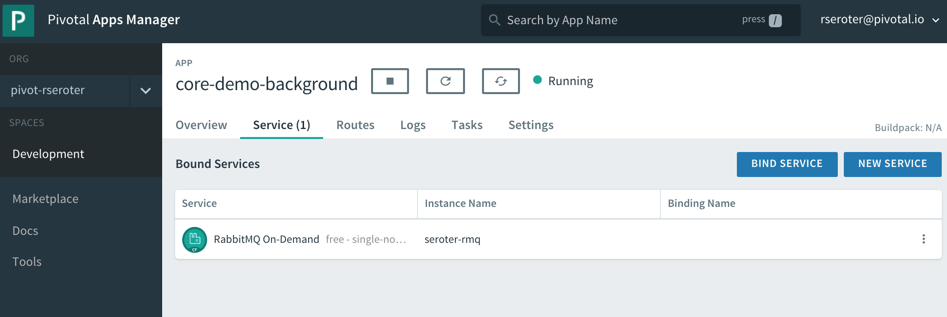

Apps deployed to Cloud Foundry are typically accompanied by a YAML manifest. You can provide the parameters on the CLI, but versioned, source-controlled manifests are a better way to go. For these background jobs, the manifests are simple. Note two key things: the no-route parameter is “true” so that we don’t get a route assigned, and the health-check-type is set to “process” so that the orchestrator monitors process availability and doesn’t try to ping a non-existent web endpoint. Also notice that I bound my app to the previously-created RabbitMQ service instance.

---

applications:

- name: core-demo-background

memory: 256M

no-route: true

health-check-type: process

services:

- seroter-rmq

After a quick cf push, my background app was running, and bound to the RabbitMQ instance.

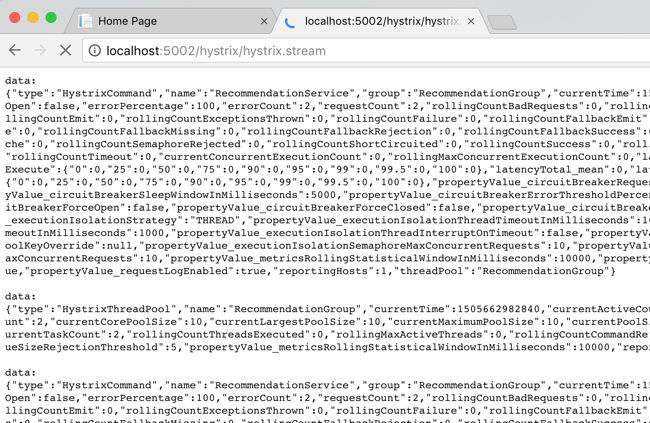

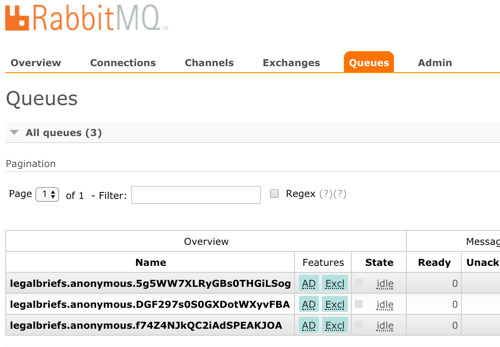

This job quietly sits and waits for work to do. What’s neat is this can also take advantage of PCF’s autoscale capability, and scale by monitoring RabbitMQ queue depth, for example. For now, one instance is plenty. I logged into RabbitMQ and sent in a couple sample “loan” messages.

Sure enough, when I viewed the aggregated application logs for my background job, I saw the content of each read message printed out.

These sorts of workers are a useful part of most systems, and PCF offers a resilient, manageable place to run them.

Deploying and running on-demand batch tasks

How many useful, random scripts do your system administrators have sitting around? You know, the ones that create users, reset demo environments, or purge FTP shares. Instead of having those scripts buried on administrator desktops, you can run these one-off batch jobs in PCF.

I created another .NET Core console application. This one pretends to sweep expired files from a shared folder. I deployed this application to PCF with a –no-start command since I want to trigger it on demand.

cf push --no-start

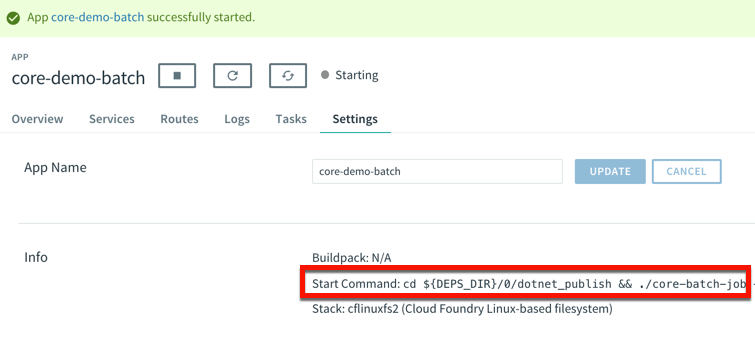

Now, to trigger the job, I need to know the start command. This depends on how you deployed it. Since I used the .NET Core buildpack, I want to start up the app one time to discover how PCF starts up the app.

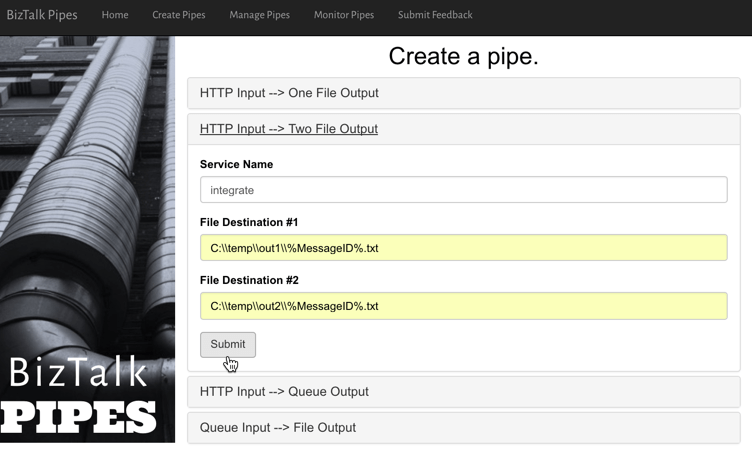

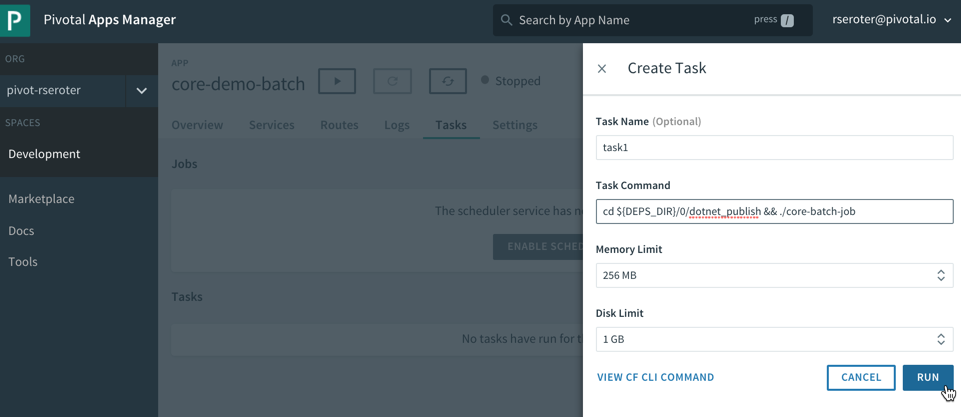

That command showed me where the .NET Core executable lives in the container. I stopped the app again, and switched over the “Tasks” view in the PCF Apps Manager interface. I can do all these things via the CLI as well, but I’m a sucker for a nice UX. There’s a “run task” button that lets me define a one-off task definition.

Here I gave the task a name, pasted the start command I found above, and that was it! When I hit, “run”, PCF instantiated a new container instance and shut down the container when the task was complete. And that’s what I saw. There was a log entry indicating a successful job run, and the application logs showed the output of the task. Nice!

This is a great option for one-off jobs and scripts. Consolidate them in PCF, and get all the availability and auditing you need.

Deploying and running scheduled jobs

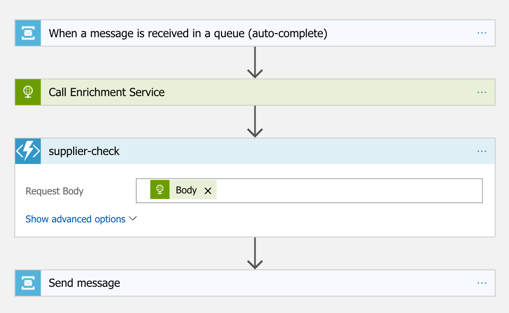

Finally, some of those one-off jobs may not be as one-off as you thought! Instead of asking your admin to trigger a task once a day to purge expired files, how about you schedule the job to run on a schedule?

PCF also offers a scheduling component to trigger tasks (or API calls!) on a recurring basis. On the same “tasks” tab of the PCF Apps Manager UX, there’s a “jobs” section for scheduled tasks. Besides giving the job a name and a command (the same as the task command above), you enter a Cron expression for the schedule itself. The expression is in a MIN HOUR DAY-OF-MONTH MONTH DAY-OF-WEEK format. For example “15 * ? * * *” means you should run the job every 15 minutes, and “30 10 * * 5” means you should run the job at 10:30am every Friday. My job below is set to run every minute.

We’re all building lots of web apps nowadays, but you have lots of need for event-driven or scheduled background work. PCF may surprise you as an entirely suitable platform for those workloads.

What a fun year. Lots of things to be grateful for. Took on some more responsibility at

What a fun year. Lots of things to be grateful for. Took on some more responsibility at