Yes, people are doing things besides generative AI. You’ve still got other problems to solve, systems to connect, and data to analyze. Apache Kafka remains a very popular product for event and data processing, and I was thinking about how someone might use it in the cloud right now. I think there are three major options, and one of them (built-in managed service) is now offered by Google Cloud. So we’ll take that for a spin.

Option 1: Run it yourself on (managed) infrastructure

Many companies choose to run Apache Kafka themselves on bare metal, virtual machines, or Kubernetes clusters. It’s easy to find stories about companies like Netflix, Pinterest, and Cloudflare running their own Apache Kafka instances. Same goes for big (and small) enterprises that choose to setup and operate dedicated Apache Kafka environments.

Why do this? It’s the usual reasons why people decide to manage their own infrastructure! Kafka has a lot of configurability, and experienced folks may like the flexibility and cost profile of running Apache Kafka themselves. Pick your infrastructure, tune every setting, and upgrade on your timetable. On the downside, self-managed Apache Kafka can result in a higher total cost of ownership, requires specialized skills in-house, and could distract you from other high-priority work.

If you want to go that route, I see a few choices.

- Download the components and install them. Grab the latest release and throw it onto a set of appropriate virtual machine instances or bare metal machines. You might use Terraform or something similar to template out the necessary activities.

- Use a pre-packaged virtual machine image. Providers like Bitnami (part of VMware, part of Broadcom) offer a catalog of packaged and supported images that contain popular software packages, including Apache Kafka. These can be deployed directly from your cloud provider as well, as I show here with Google Cloud.

- Deploy to Kubernetes. Nowadays, it’s reasonable to deploy rich, stateful workloads to a Kubernetes cluster. You might use a Helm chart from someone like Bitnami. Here’s great documentation for deploying a highly available Apache Kafka cluster to GKE using Terraform. I also like the Kubernetes operator pattern and Strimzi makes this fairly easy. Check out this documentation for using Strimzi and operators to create Apache Kafka clusters in GKE.

There’s no shame in going this route! It’s actually very useful to know how to run software like Apache Kafka yourself, even if you decide to switch to a managed service later.

Option 2: Use a built-in managed service

You might want Apache Kafka, but not want to run Apache Kafka. I’m with you. Many folks, including those at big web companies and classic enterprises, depend on managed services instead of running the software themselves.

Why do this? You’d sign up for this option when you want the API, but not the ops. It may be more elastic and cost-effective than self-managed hosting. Or, it might cost more from a licensing perspective, but provide more flexibility on total cost of ownership. On the downside, you might not have full access to every raw configuration option, and may pay for features or vendor-dictated architecture choices you wouldn’t have made yourself.

AWS offers an Amazon Managed Streaming for Apache Kafka product. Microsoft doesn’t offer a managed Kafka product, but does provide a subset of the Apache Kafka API in front of their Azure Event Hubs product. Oracle cloud offers self-managed infrastructure with a provisioning assist, but also appears to have a compatible interface on their Streaming service.

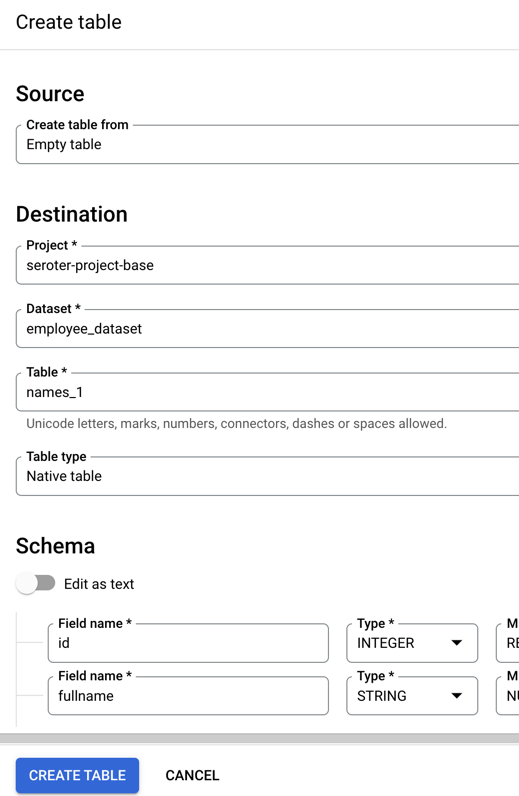

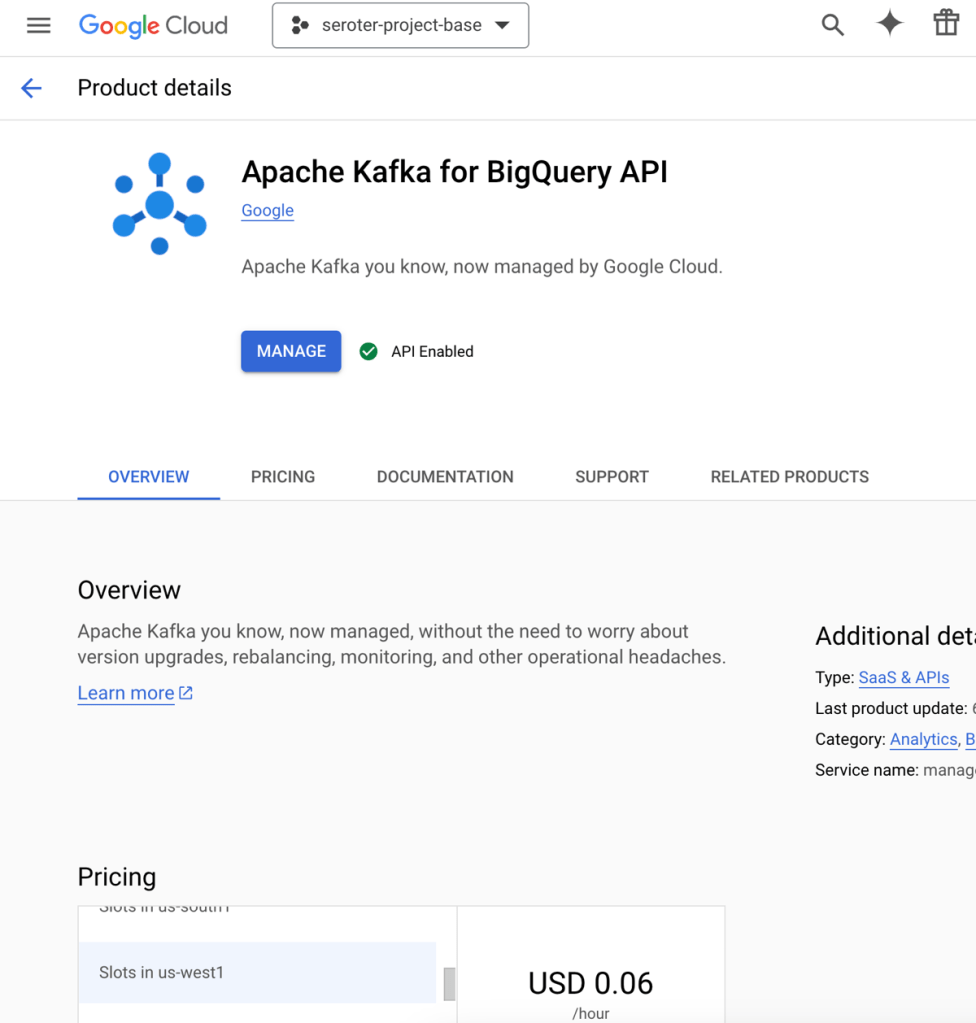

Google Cloud didn’t offer any native service until just a couple of months ago. The Apache Kafka for BigQuery product is now in preview and looks pretty interesting. It’s available in a global set of regions, and provides a fully-managed set of brokers that run in a VPC within a tenant project. Let’s try it out.

Set up prerequisites

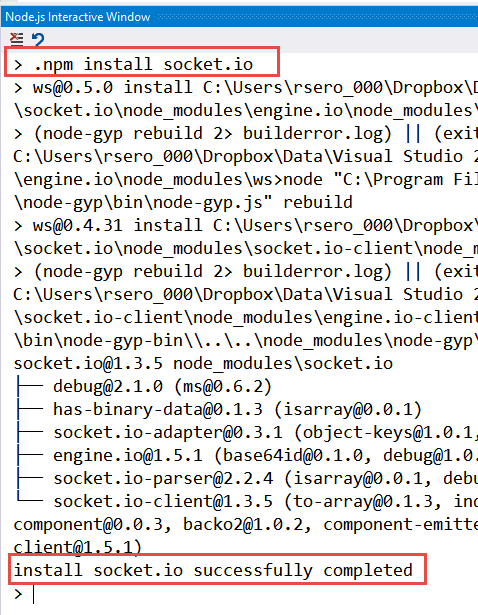

First, I needed to enable the API within Google Cloud. This gave me the ability to use the service. Note that this is NOT FREE while in preview, so recognize that you’ll incur changes.

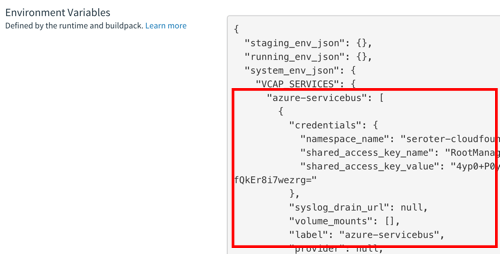

Next, I wanted a dedicated service account for accessing the Kafka service from client applications. The service supports OAuth and SASL_PLAIN with service account keys. The latter is appropriate for testing, so I chose that.

I created a new service account named seroter-bq-kafka and gave it the roles/managedkafka.client role. I also created a JSON private key and saved it to my local machine.

That’s it. Now I was ready to get going with the cluster.

Provision the cluster and topic

I went into the Apache Kafka for BigQuery dashboard in the Google Cloud console—I could have also used the CLI which has the full set of control plane commands—to spin up a new cluster. I get very few choices, and that’s not a bad thing. You give the CPU and RAM capacity for the cluster, and Google Cloud creates the right shape for the brokers, and creates a highly available architecture. You’ll also see that I choose the VPC for the cluster, but that’s about it. Pretty nice!

In about twenty minutes, my cluster was ready. Using the console or CLI, I could see the details of my cluster.

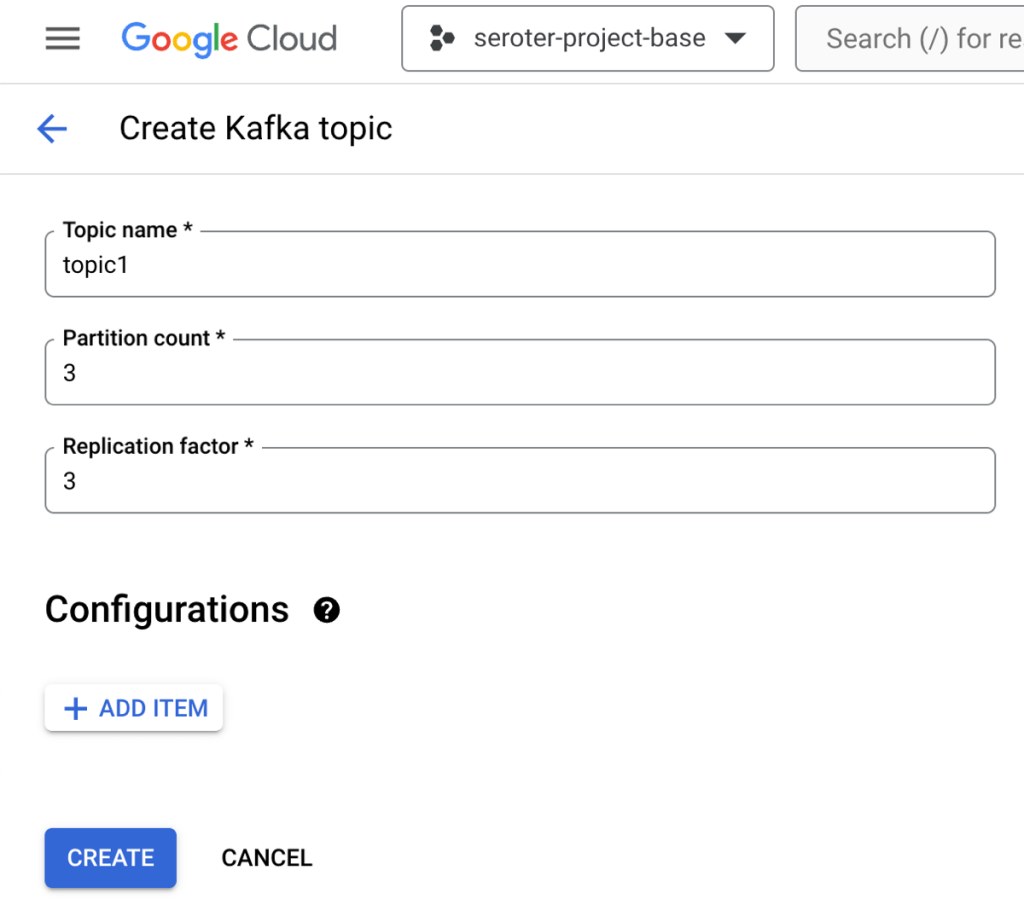

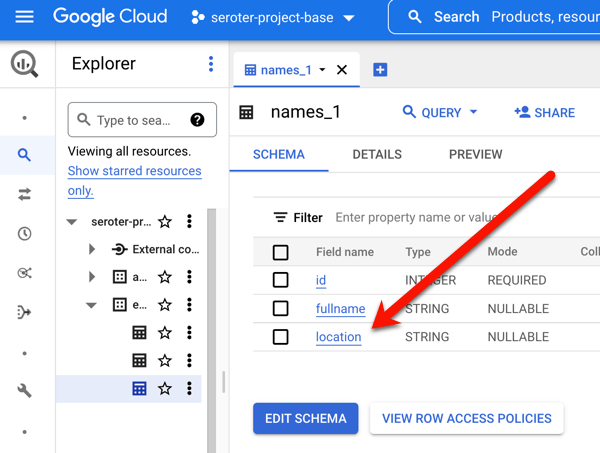

Topics are a core part of Apache Kafka represent the resource you publish and subscribe to. I could create a topic via the UI or CLI. I created a topic called “topic1”.

Build the producer and consumer apps

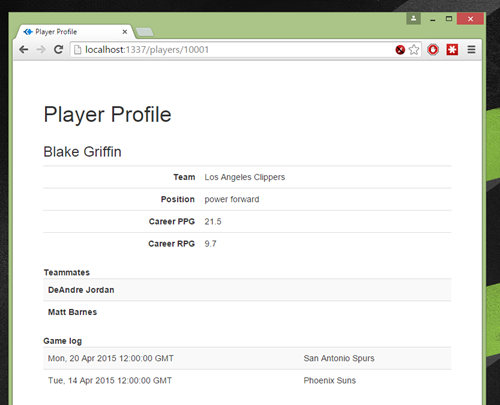

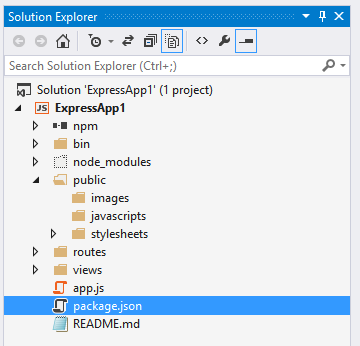

I wanted two client apps. One to publish new messages to Apache Kafka, and another to consume messages. I chose Node.js and JavaScript as the language for the app. There are a handful of libraries for interacting with Apache Kafka, and I chose the mature kafkajs.

Let’s start with the consuming app. I need (a) the cluster’s bootstrap server URL and (b) the encoded client credentials. We access the cluster through the bootstrap URL and it’s accessible via the CLI or the cluster details (see above). The client credentials for SASL_PLAIN authentication consists of the base64 encoded service account key JSON file.

My index.js file defines a Kafka object with the client ID (which identifies our consumer), the bootstrap server URL, and SASL credentials. Then I define a consumer with a consumer group ID and subscribe to the “topic1” we created earlier. I process and log each message before appending to an array variable. There’s an HTTP GET endpoint that returns the array. See the whole index.js below, and the GitHub repo here.

const express = require('express');

const { Kafka, logLevel } = require('kafkajs');

const app = express();

const port = 8080;

const kafka = new Kafka({

clientId: 'seroter-consumer',

brokers: ['bootstrap.seroter-kafka.us-west1.managedkafka.seroter-project-base.cloud.goog:9092'],

ssl: {

rejectUnauthorized: false

},

logLevel: logLevel.DEBUG,

sasl: {

mechanism: 'plain', // scram-sha-256 or scram-sha-512

username: 'seroter-bq-kafka@seroter-project-base.iam.gserviceaccount.com',

password: 'tybgIC ... pp4Fg=='

},

});

const consumer = kafka.consumer({ groupId: 'message-retrieval-group' });

//create variable that holds an array of "messages" that are strings

let messages = [];

async function run() {

await consumer.connect();

//provide topic name when subscribing

await consumer.subscribe({ topic: 'topic1', fromBeginning: true });

await consumer.run({

eachMessage: async ({ topic, partition, message }) => {

console.log(`################# Received message: ${message.value.toString()} from topic: ${topic}`);

//add message to local array

messages.push(message.value.toString());

},

});

}

app.get('/consume', (req, res) => {

//return the array of messages consumed thus far

res.send(messages);

});

run().catch(console.error);

app.listen(port, () => {

console.log(`App listening at http://localhost:${port}`);

});

Now we switch gears and go through the producer app that publishes to Apache Kafka.

This app starts off almost identically to the consumer app. There’s a Kafka object with a client ID (different for the producer) and the same pointer to the bootstrap server URL and credentials. I’ve got an HTTP GET endpoint that takes the querystring parameters and publishes the key and value content to the request payload. The code is below, and the GitHub repo is here.

const express = require('express');

const { Kafka, logLevel } = require('kafkajs');

const app = express();

const port = 8080; // Use a different port than the consumer app

const kafka = new Kafka({

clientId: 'seroter-publisher',

brokers: ['bootstrap.seroter-kafka.us-west1.managedkafka.seroter-project-base.cloud.goog:9092'],

ssl: {

rejectUnauthorized: false

},

logLevel: logLevel.DEBUG,

sasl: {

mechanism: 'plain', // scram-sha-256 or scram-sha-512

username: 'seroter-bq-kafka@seroter-project-base.iam.gserviceaccount.com',

password: 'tybgIC ... pp4Fg=='

},

});

const producer = kafka.producer();

app.get('/publish', async (req, res) => {

try {

await producer.connect();

const _key = req.query.key; // Extract key from querystring

console.log('key is ' + _key);

const _value = req.query.value // Extract value from querystring

console.log('value is ' + _value);

const message = {

key: _key, // Optional key for partitioning

value: _value

};

await producer.send({

topic: 'topic1', // Replace with your topic name

messages: [message]

});

res.status(200).json({ message: 'Message sent successfully' });

} catch (error) {

console.error('Error sending message:', error);

res.status(500).json({ error: 'Failed to send message' });

}

});

app.listen(port, () => {

console.log(`Producer listening at http://localhost:${port}`);

});

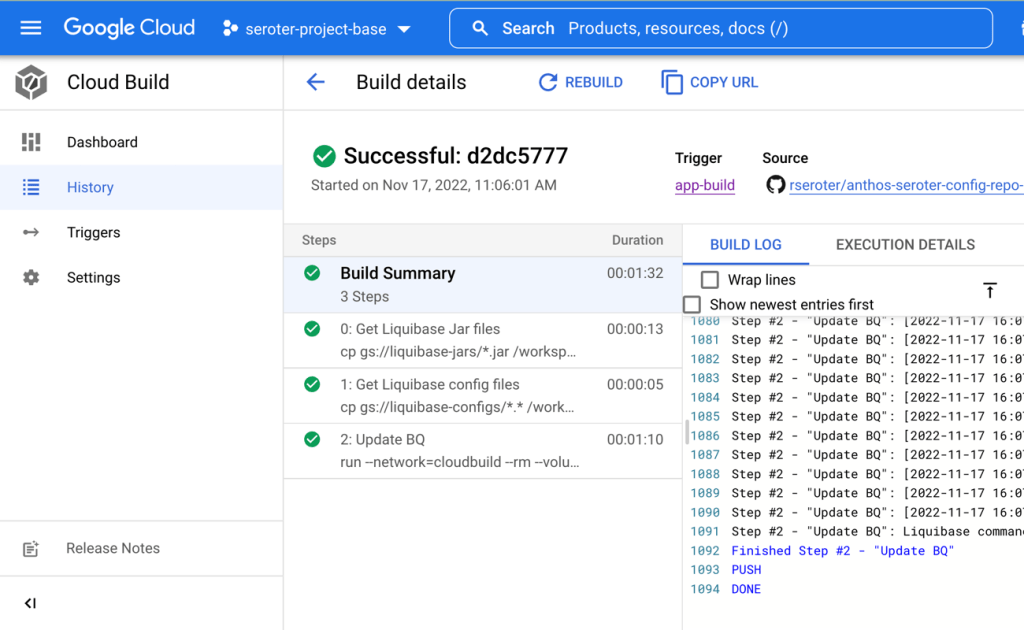

Next up, containerizing both apps so that I could deploy to a runtime.

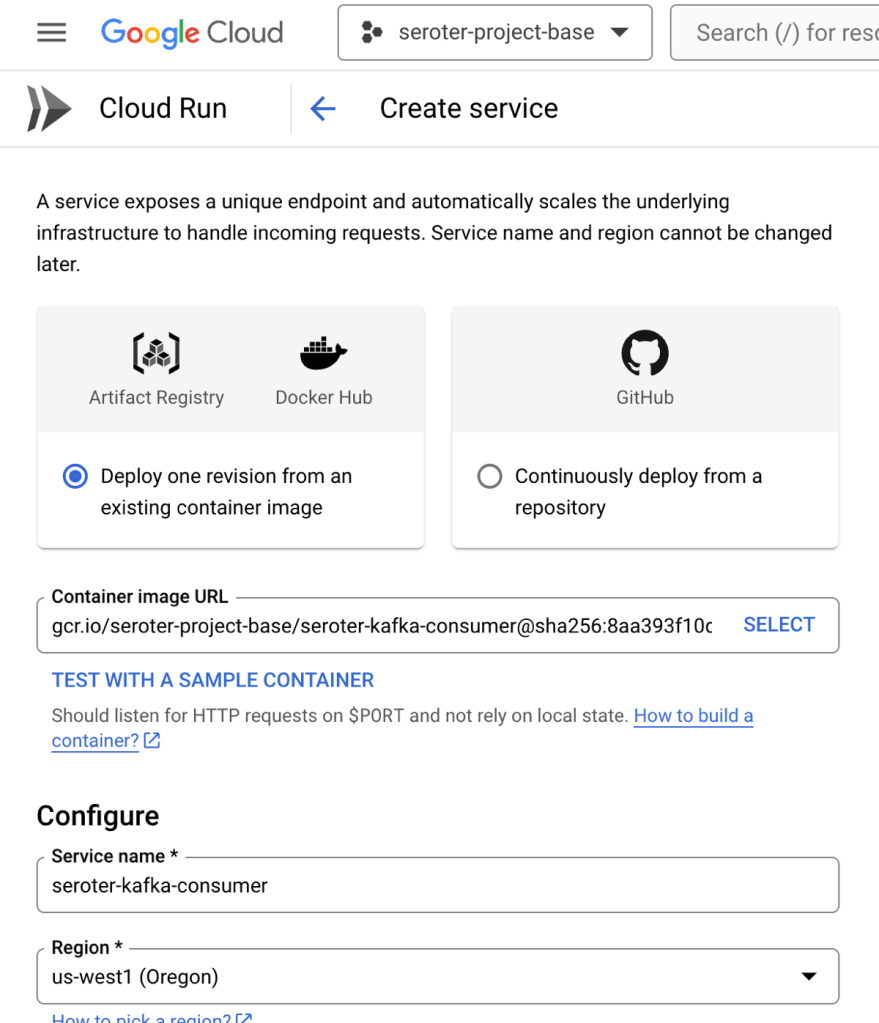

I used Google Cloud Artifact Registry as my container store, and created a Docker image from source code using Cloud Native buildpacks. It took one command for each app:

gcloud builds submit --pack image=gcr.io/seroter-project-base/seroter-kafka-consumer

gcloud builds submit --pack image=gcr.io/seroter-project-base/seroter-kafka-publisher

Now we had everything needed to deploy and test our client apps.

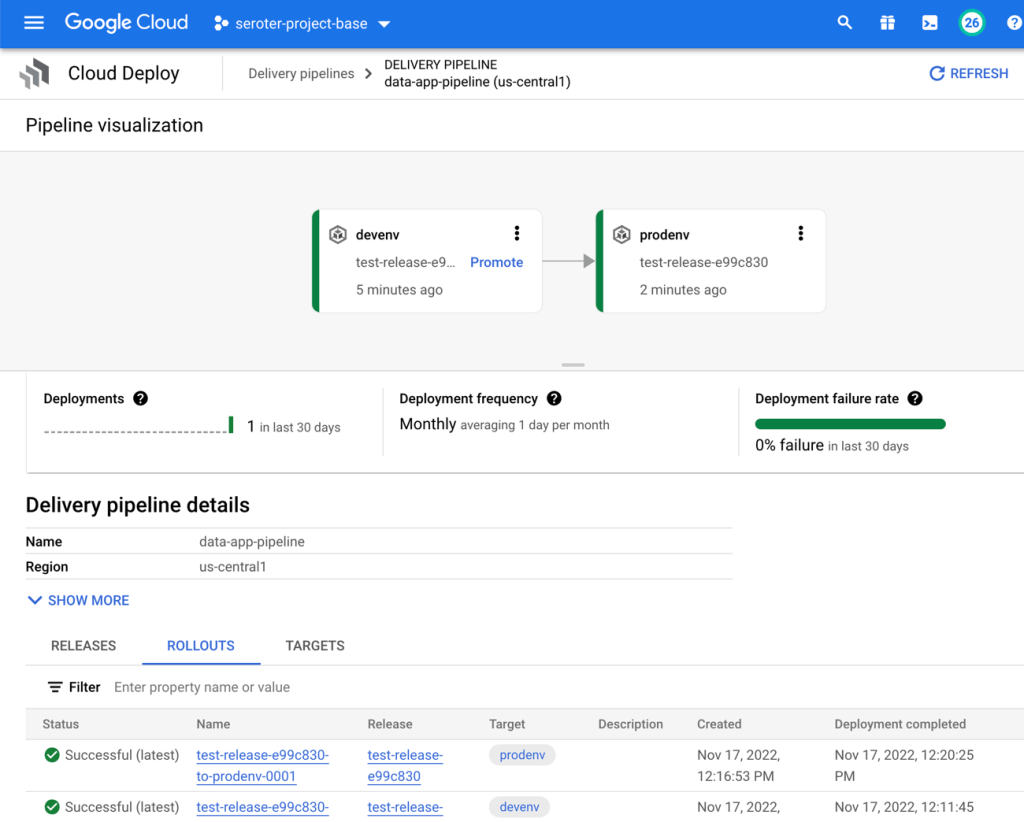

Deploy apps to Cloud Run and test it out

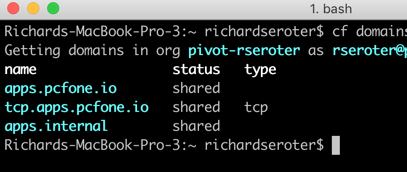

I chose Google Cloud Run because I like nice things. It’s still one of the best two or three ways to host apps in the cloud. We also make it much easier now to connect to a VPC, which is what I need. Instead of creating some tunnel out of my cluster, I’d rather access it more securely.

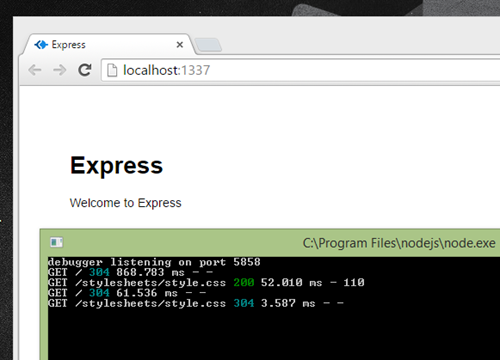

Here’s how I configured the consuming app. I first picked my container image and a target location.

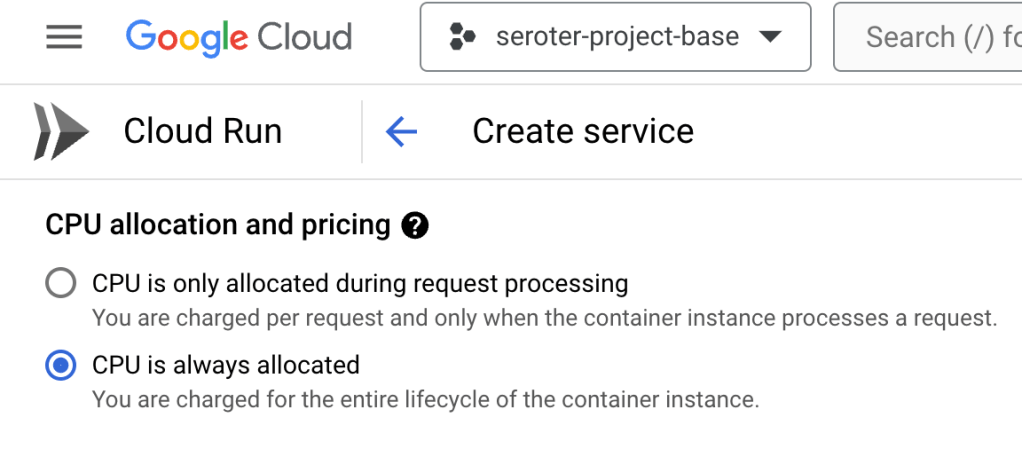

Then I chose to use always-on CPU for the consumer, as I had connection issues when I had a purely ephemeral container.

The last setting was the VPC egress that made it possible for this instance to talk to the Apache Kafka cluster.

About three seconds later, I had a running Cloud Run instance ready to consume.

I ran through a similar deployment process for the publisher app, except I kept the true “scale to zero” setting turned on since it doesn’t matter if the publisher app comes and goes.

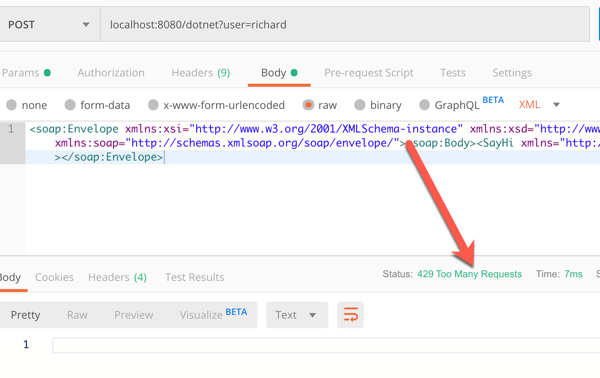

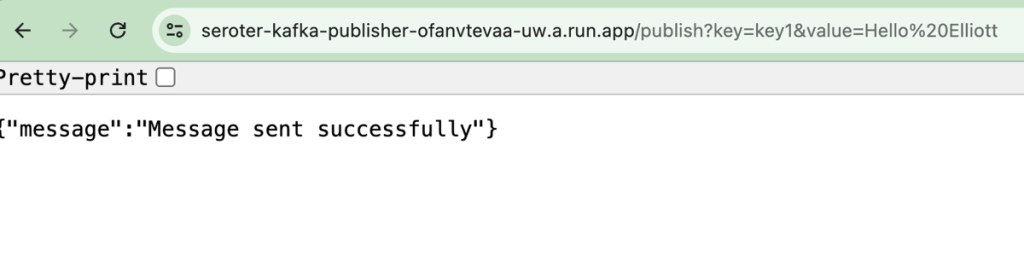

With all apps deployed, I fired up the browser and issued a pair of requests to the “publish” endpoint.

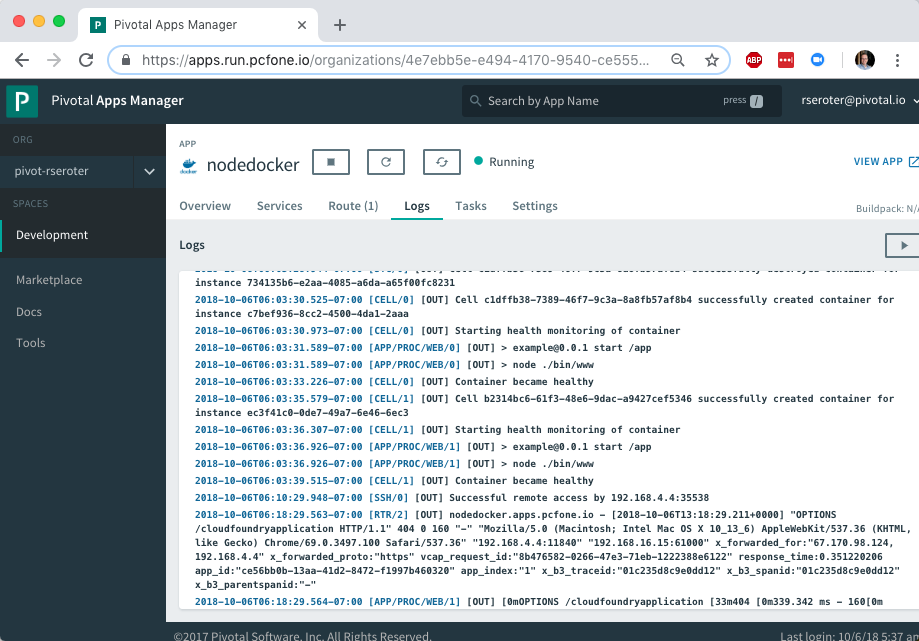

I checked the consumer app’s logs and saw that messages were successfully retrieved.

Sending a request to the GET endpoint on the consumer app returns the pair of messages I sent from the publisher app.

Sweet! We proved that we could send messages to the Apache Kafka cluster, and retrieve them. I get all the benefits of Apache Kafka, integrated into Google Cloud, with none of the operational toil.

Read more in the docs about this preview service.

Option 3: Use a managed provider on your cloud(s) of choice

The final way you might choose to run Apache Kafka in the cloud is to use a SaaS product designed to work on different infrastructures.

The team at Confluent does much of the work on open source Apache Kafka and offers a managed product via Confluent Cloud. It’s performant, feature-rich, and runs in AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud. Another option is Redpanda, who offer a managed cloud service that they operate on their infrastructure in AWS or Google Cloud.

Why do this? Choosing a “best of breed” type of managed service is going to give you excellent feature coverage and operational benefits. These platforms are typically operated by experts and finely tuned for performance and scale. Are there any downside? These platforms aren’t free, and don’t always have all the native integrations into their target cloud (logging, data services, identity, etc) that a built-in service does. And you won’t have all the configurability or infrastructure choice that you’d have running it yourself.

Wrap up

It’s a great time to run Apache Kafka in the cloud. You can go full DIY or take advantage of managed services. As always, there are tradeoffs with each. You might even use a mix of products and approaches for different stages (dev/test/prod) and departments within your company. Are there any options I missed? Let me know!