If it seems to you that cloud providers offer distinct compute services for every specific type of workload, you’re not imagining things. Fifteen years ago when I was building an app, my hosting choices included a virtual machine or a physical server. Today? You’ll find services targeting web apps, batch apps, commercial apps, containerized apps, Windows apps, Spring apps, VMware-based apps, and more. It’s a lot. So, it catches my eye when I find a modern cloud service that support a few different types of workloads. Our serverless compute service Google Cloud Run might be the fastest and easiest way to get web apps running in the cloud, and we just added support for background jobs. I figured I’d try out Cloud Run for three distinct scenarios: web app (responds to HTTP requests, scales to zero), job (triggered, runs to completion), and worker (processes background work continuously).

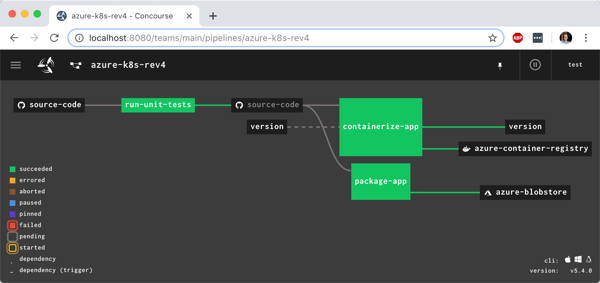

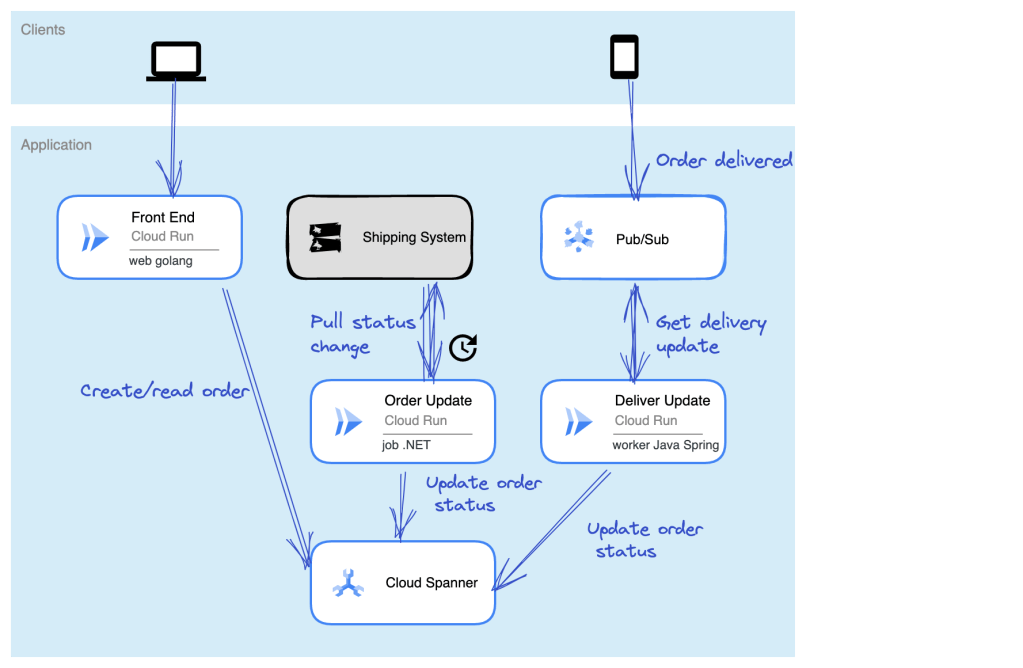

Let’s make this scenario come alive. I want a web interface that takes in “orders” and shows existing orders (via Cloud Run web app). There’s a separate system that prepares orders for delivery and we poll that system occasionally (via Cloud Run job) to update the status of our orders. And when the order itself is delivered, the mobile app used by the delivery-person sends a message to a queue that a worker is constantly listening to (via Cloud Run app). The basic architecture is something like this:

Ok, how about we build it out!

Setting up our Cloud Spanner database

The underlying database for this system is Cloud Spanner. Why? Because it’s awesome and I want to start using it more. Now, I should probably have a services layer sitting in front of the database instead of doing direct read/write, but this is my demo and I’ll architect however I damn well please!

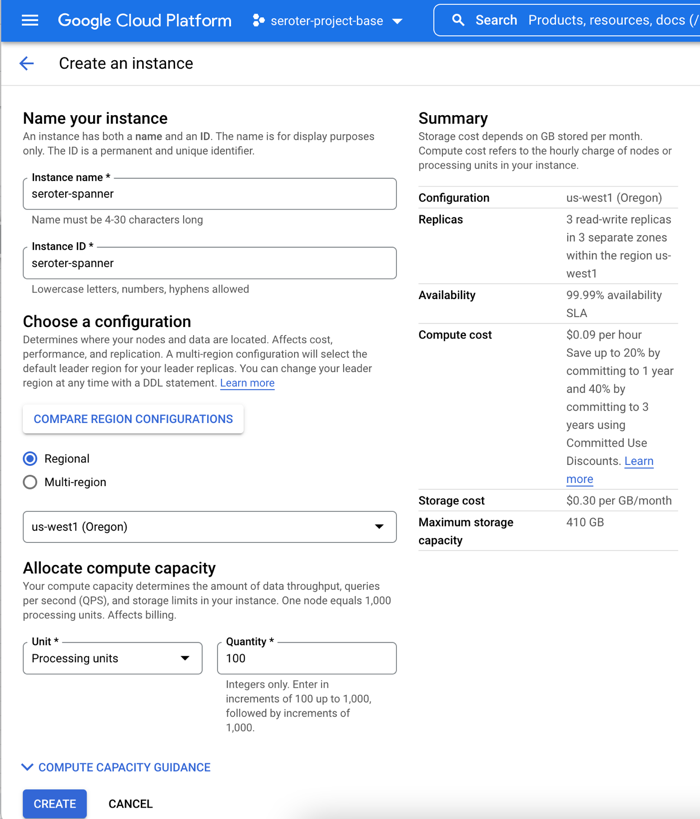

I started by creating a Spanner instance. We’ve recently made it possible to create smaller instances, which means you can get started at less cost, without sacrificing resilience. Regardless of the number of “processing units” I choose, I get 3 replicas and the same availability SLA. The best database in the cloud just got a lot more affordable.

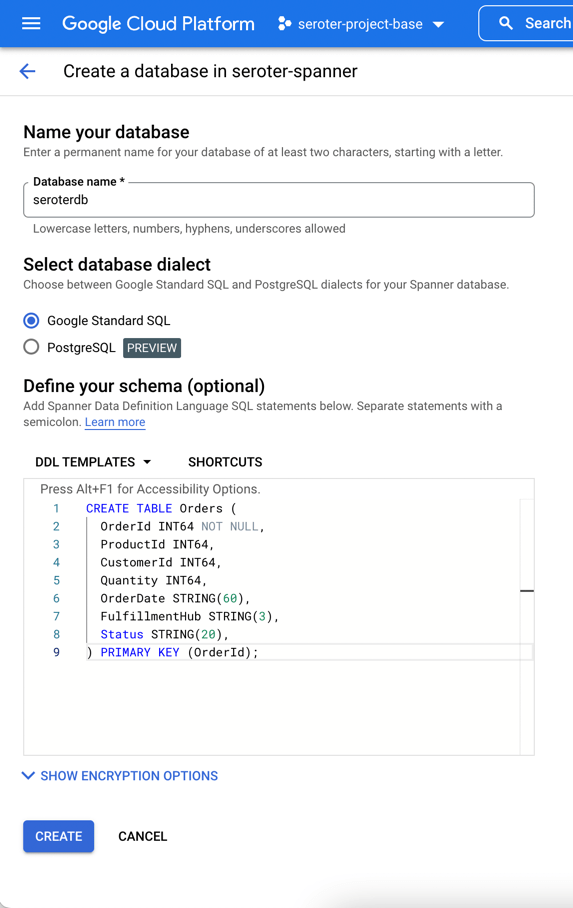

Next, I add a database to this instance. After giving it a name, I choose the “Google Standard SQL” option, but I could have also chosen a PostgreSQL interface. When defining my schema, I like that we offer script templates for actions like “create table”, “create index”, and “create change stream.” Below, you see my table definition.

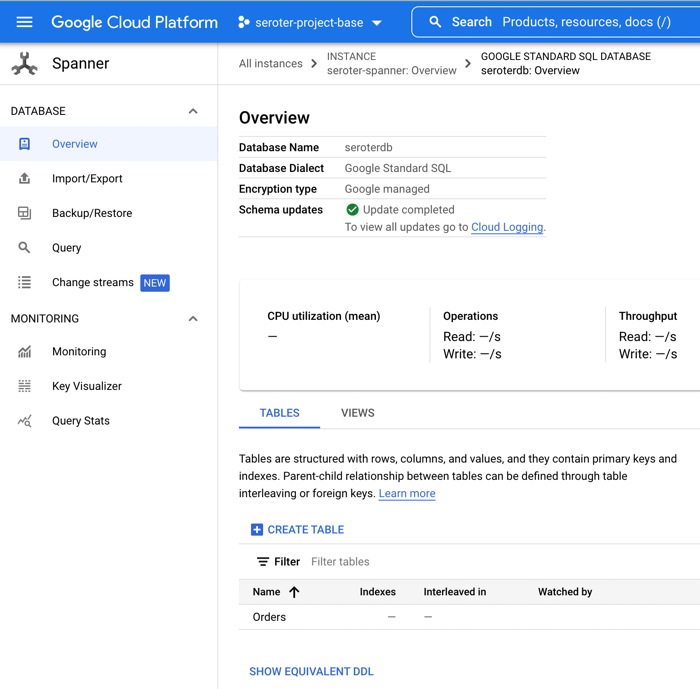

With that, I have a database. There’s nothing left to do, besides bask in the glory of having a regionally-deployed, highly available relational database instance at my disposal in about 60 seconds.

Creating the web app in Go and deploying to Cloud Run

With the database in place, I can build a web app with read/write capabilities.

This app is written in Go and uses the echo web framework. I defined a basic struct that matches the fields in the database.

package model

type Order struct {

OrderId int64

ProductId int64

CustomerId int64

Quantity int64

Status string

OrderDate string

FulfillmentHub string

}

I’m using the Go driver for Spanner and the core of the logic consists of the operations to retrieve Spanner data and create a new record. I need to be smarter about reusing the connection, but I’ll refactor it later. Narrator: He probably won’t refactor it.

package web

import (

"context"

"log"

"time"

"cloud.google.com/go/spanner"

"github.com/labstack/echo/v4"

"google.golang.org/api/iterator"

"seroter.com/serotershop/model"

)

func GetOrders() []*model.Order {

//create empty slice

var data []*model.Order

//set up context and client

ctx := context.Background()

db := "projects/seroter-project-base/instances/seroter-spanner/databases/seroterdb"

client, err := spanner.NewClient(ctx, db)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer client.Close()

//get all the records in the table

iter := client.Single().Read(ctx, "Orders", spanner.AllKeys(), []string{"OrderId", "ProductId", "CustomerId", "Quantity", "Status", "OrderDate", "FulfillmentHub"})

defer iter.Stop()

for {

row, e := iter.Next()

if e == iterator.Done {

break

}

if e != nil {

log.Println(e)

}

//create object for each row

o := new(model.Order)

//load row into struct that maps to same shape

rerr := row.ToStruct(o)

if rerr != nil {

log.Println(rerr)

}

//append to collection

data = append(data, o)

}

return data

}

func AddOrder(c echo.Context) {

//retrieve values

orderid := c.FormValue("orderid")

productid := c.FormValue("productid")

customerid := c.FormValue("customerid")

quantity := c.FormValue("quantity")

status := c.FormValue("status")

hub := c.FormValue("hub")

orderdate := time.Now().Format("2006-01-02")

//set up context and client

ctx := context.Background()

db := "projects/seroter-project-base/instances/seroter-spanner/databases/seroterdb"

client, err := spanner.NewClient(ctx, db)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer client.Close()

//do database table write

_, e := client.Apply(ctx, []*spanner.Mutation{

spanner.Insert("Orders",

[]string{"OrderId", "ProductId", "CustomerId", "Quantity", "Status", "FulfillmentHub", "OrderDate"},

[]interface{}{orderid, productid, customerid, quantity, status, hub, orderdate})})

if e != nil {

log.Println(e)

}

}

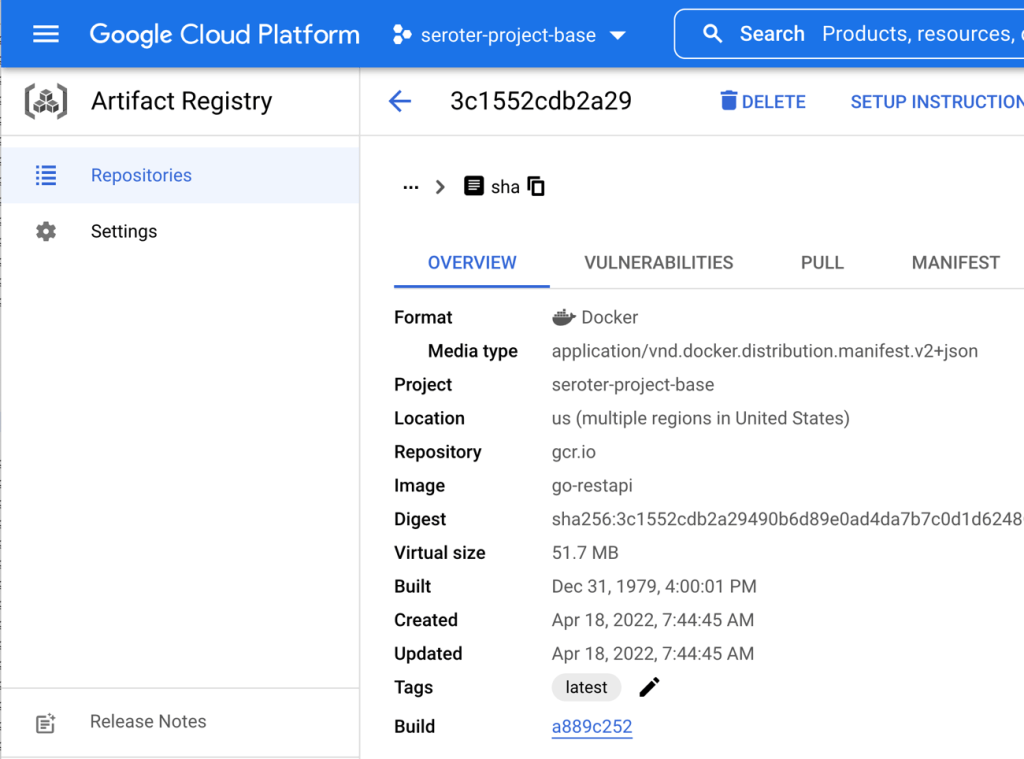

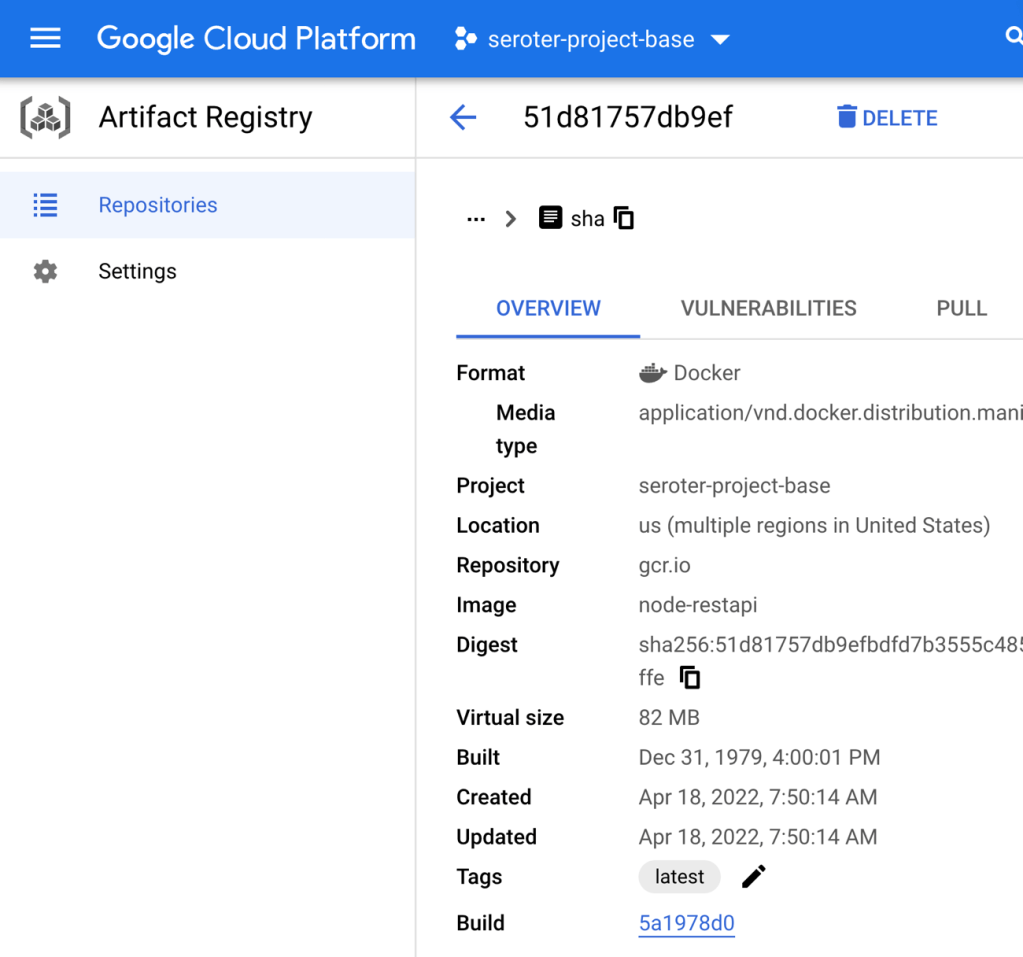

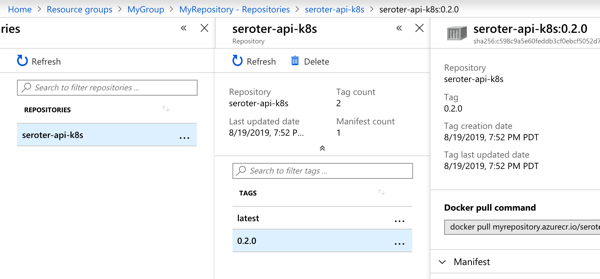

Time to deploy! I’m using Cloud Build to generate a container image without using a Dockerfile. A single command triggers the upload, build, and packaging of my app.

gcloud builds submit --pack image=gcr.io/seroter-project-base/seroter-run-web

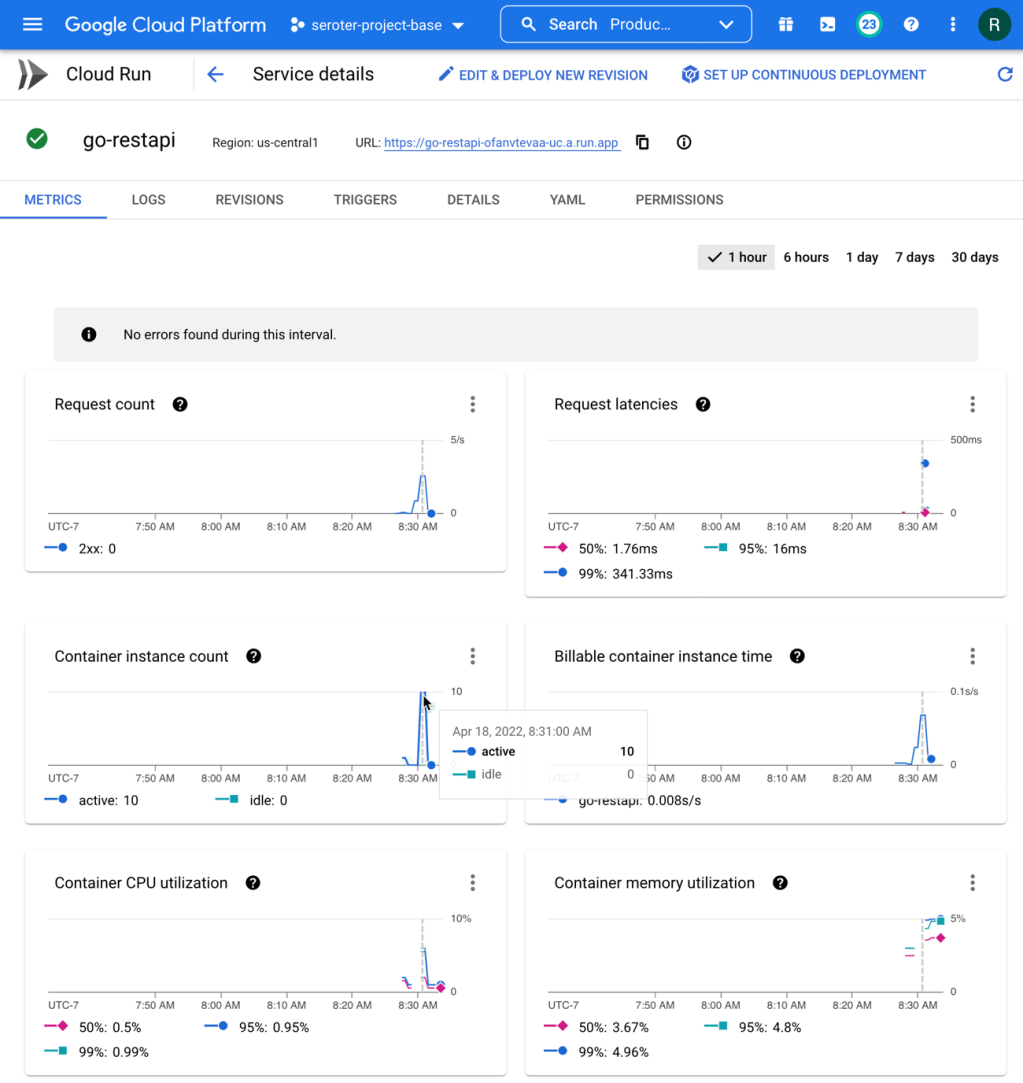

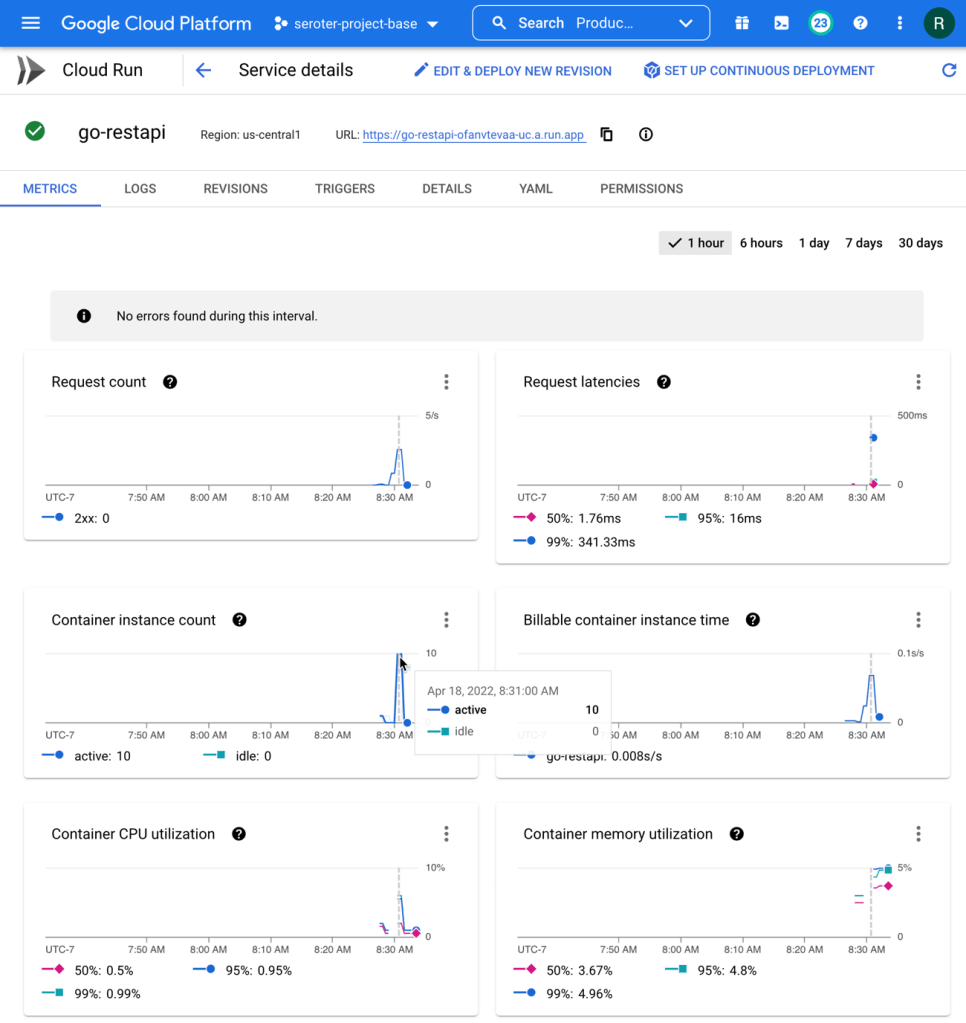

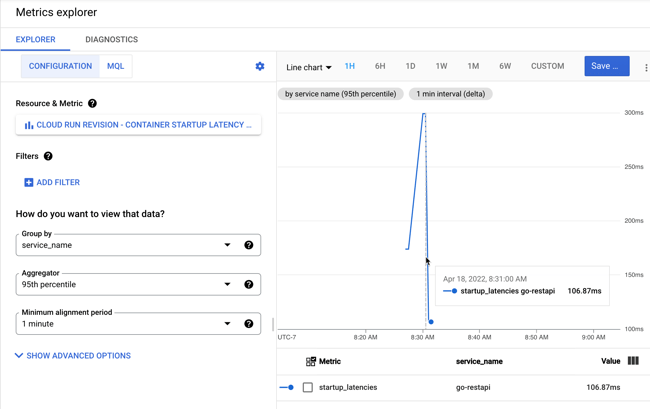

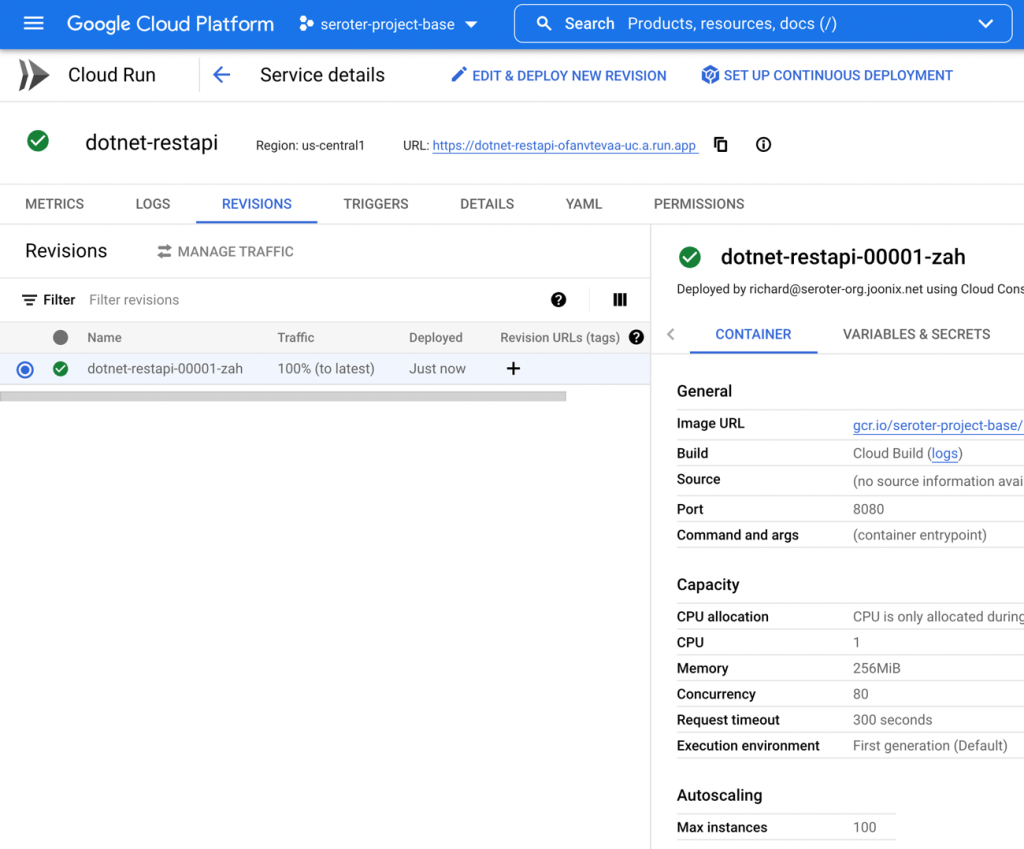

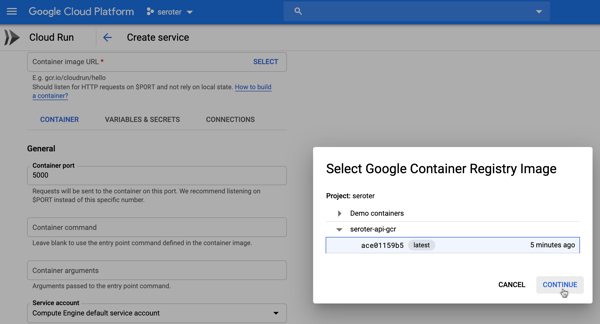

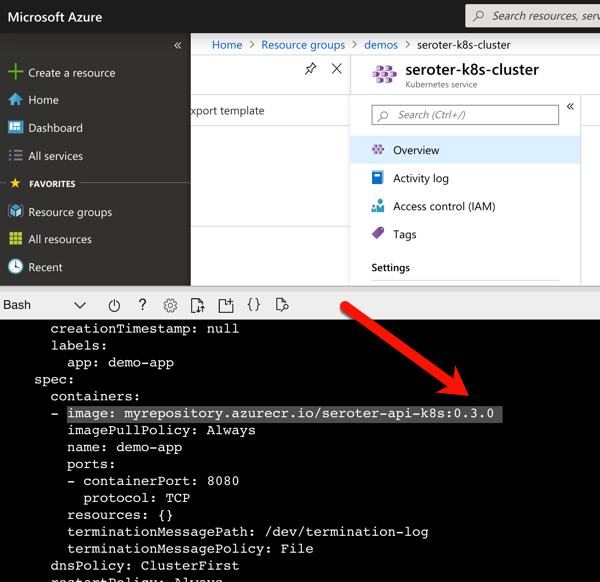

After a moment, I have a container image ready to go. I jumped in the Cloud Run experience and chose to create a new service. After picking the container image I just created, I kept the default autoscaling (minimum of zero instances), concurrency, and CPU allocation settings.

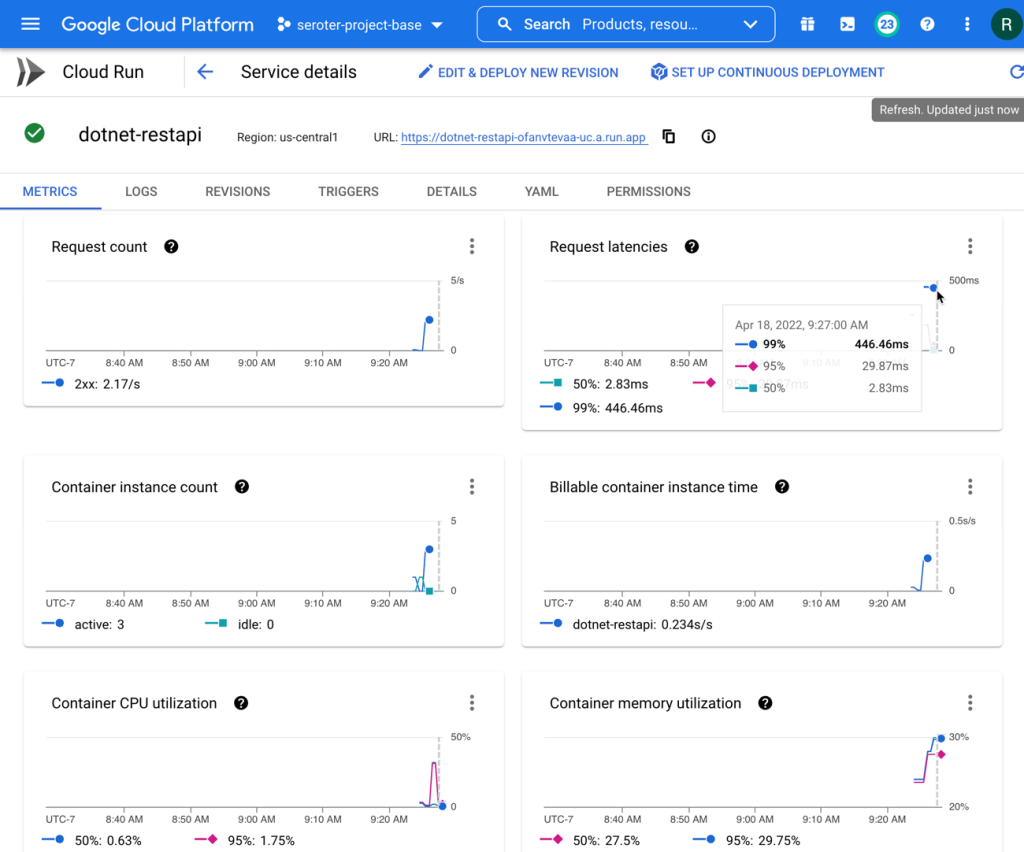

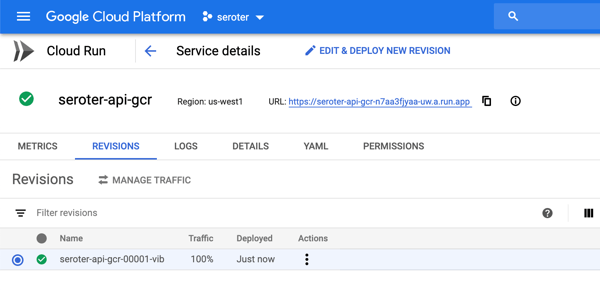

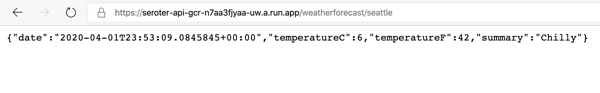

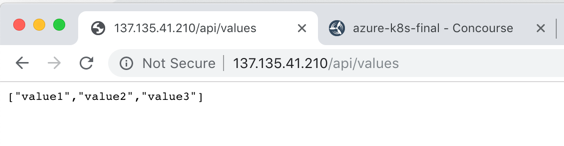

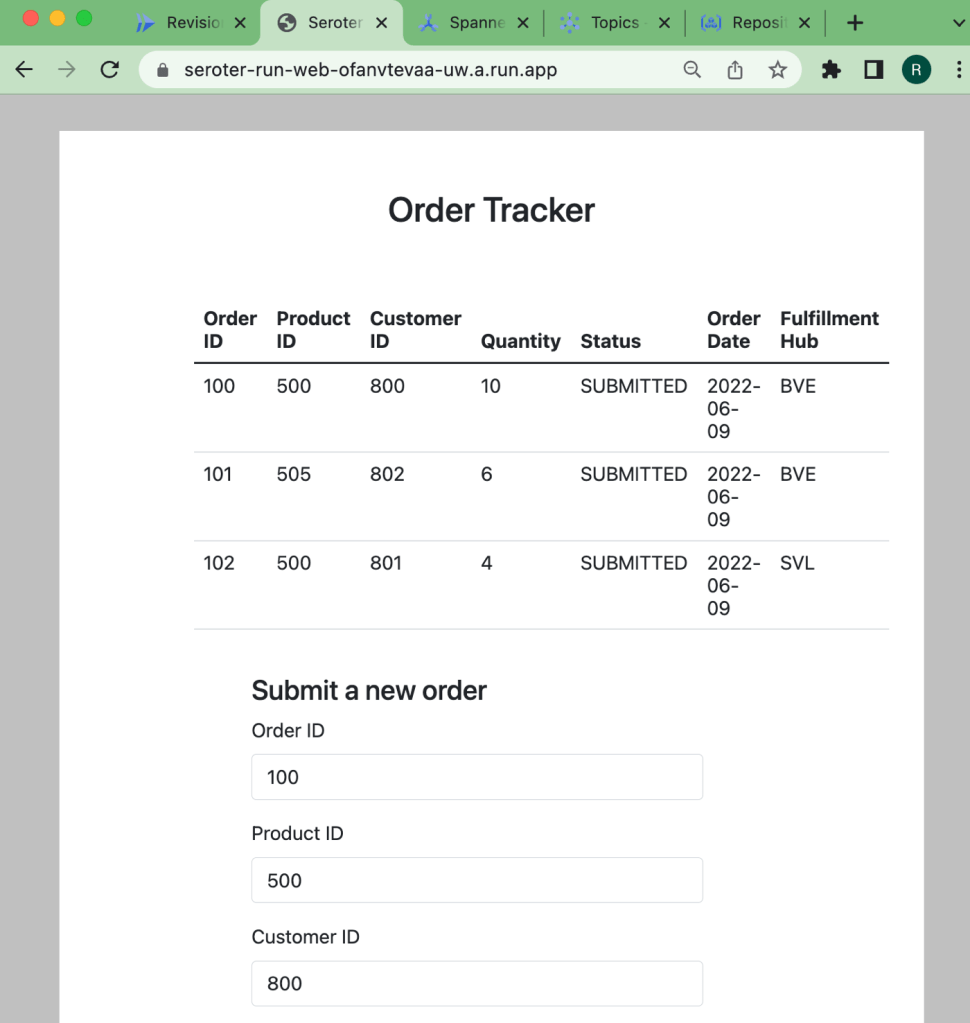

The app started in seconds, and when I call up the URL, I see my application. And I went ahead and submitted a few orders, which then show up in the list.

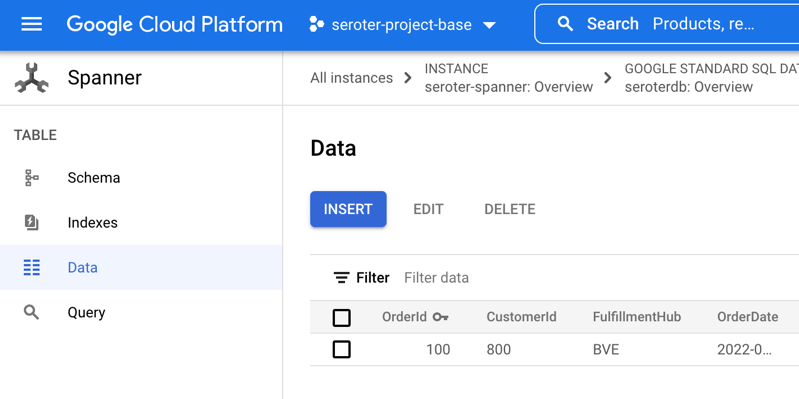

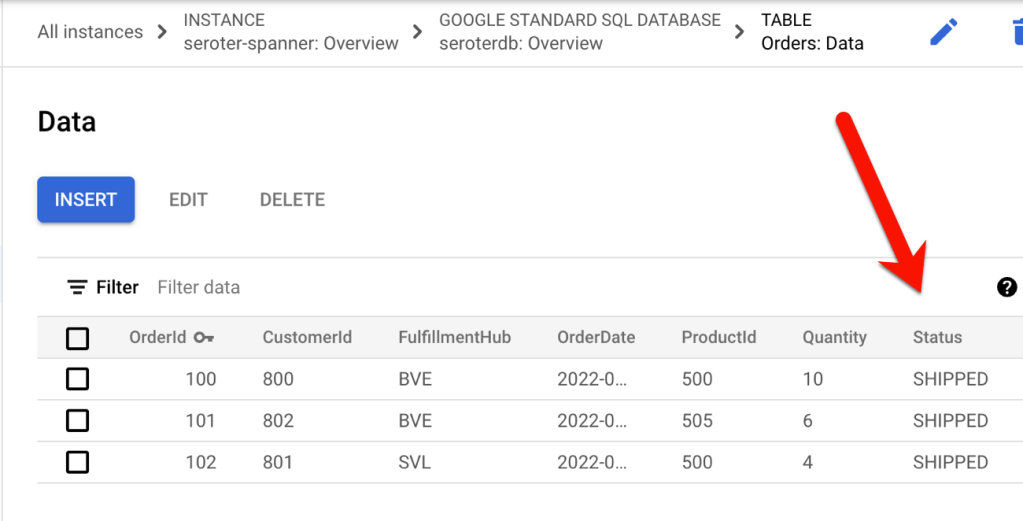

Checking Cloud Spanner—just to ensure this wasn’t only data sitting client-side—shows that I have rows in my database table.

Ok, my front end web application is running (when requests come in) and successfully talking to my Cloud Spanner database.

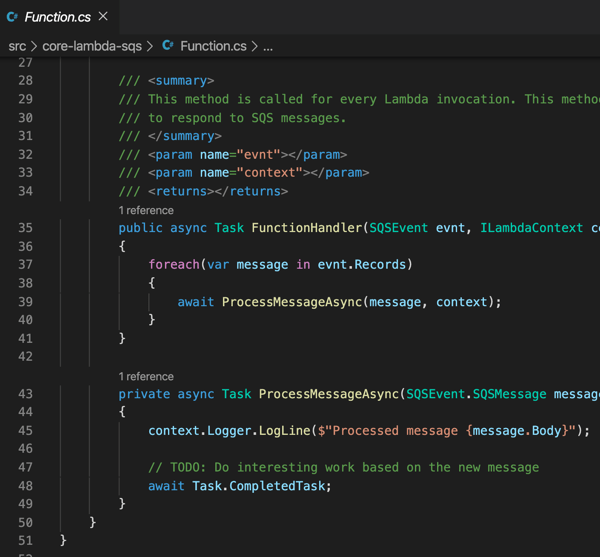

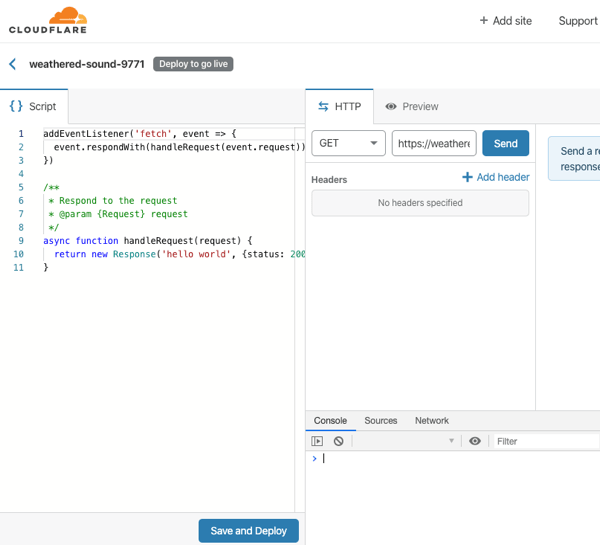

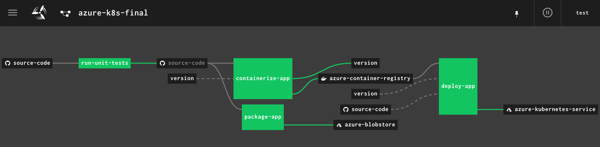

Creating the batch processor in .NET and deploying to Cloud Run jobs

As mentioned in the scenario summary, let’s assume we have some shipping system that prepares the order for delivery. Every so often, we want to poll that system for changes, and update the order status in the Spanner database accordingly.

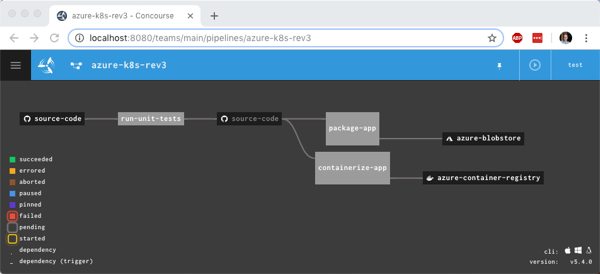

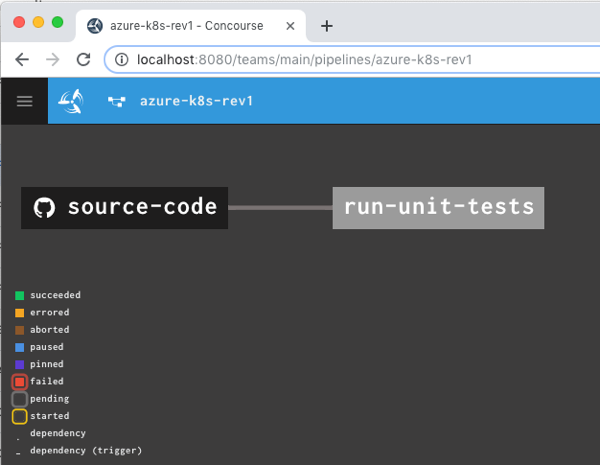

Until lately, you’d run these batch jobs in App Engine, Functions, a GKE pod, or some other compute service that you could trigger on a schedule. But we just previewed Cloud Run jobs which offers a natural choice moving forward. Here, I can run anything that can be containerized, and the workload runs until completion. You might trigger these via Cloud Scheduler, or kick them off manually.

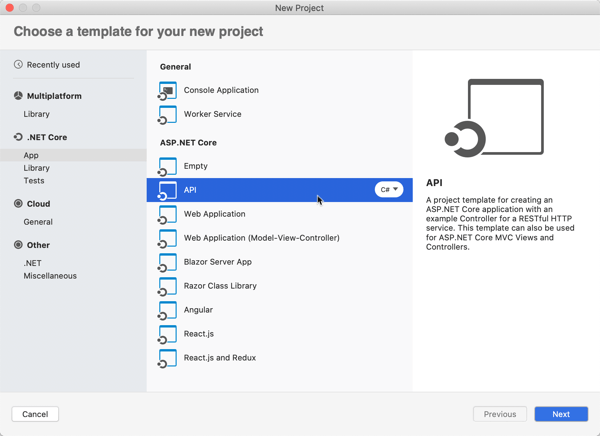

Let’s write a .NET console application that does the work. I’m using the new minimal API that hides a bunch of boilerplate code. All I have is a Program.cs file, and a package dependency on Google.Cloud.Spanner.Data. Because I don’t like you THAT much, I didn’t actually create a stub for the shipping system, and decided to update the status of all the rows at once.

using Google.Cloud.Spanner.Data;

Console.WriteLine("Starting job ...");

//connection string

string conn = "Data Source=projects/seroter-project-base/instances/seroter-spanner/databases/seroterdb";

using (var connection = new SpannerConnection(conn)) {

//command that updates all rows with the initial status

SpannerCommand cmd = connection.CreateDmlCommand("UPDATE Orders SET Status = 'SHIPPED' WHERE Status = 'SUBMITTED'");

//execute and hope for the best

cmd.ExecuteNonQuery();

}

//job should end after this

Console.WriteLine("Update done. Job completed.");

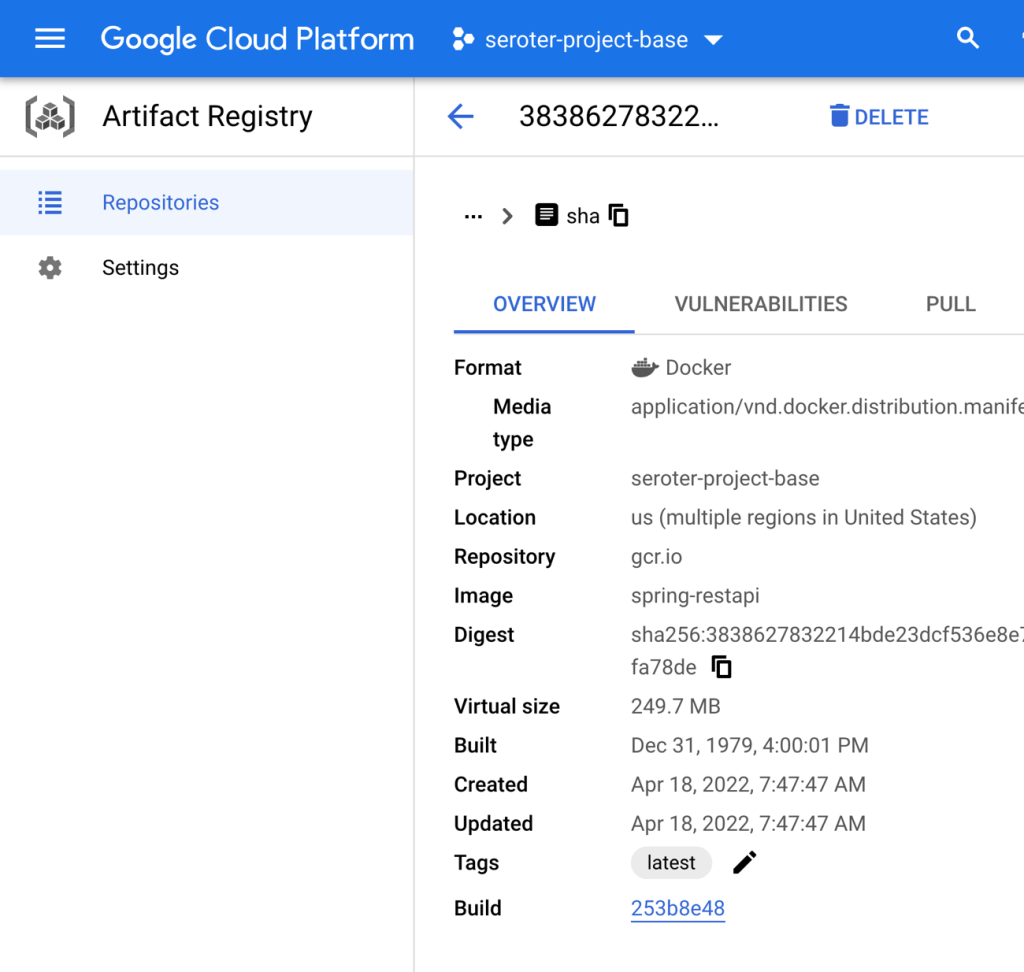

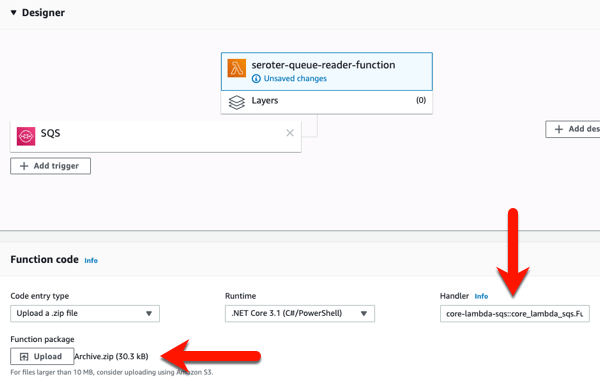

Like before, I use a single Cloud Build command to compile and package my app into a container image: gcloud builds submit --pack image=gcr.io/seroter-project-base/seroter-run-job

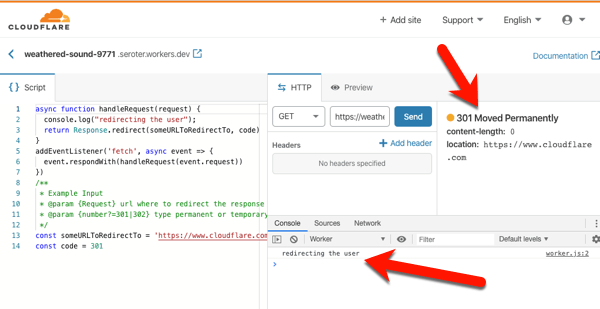

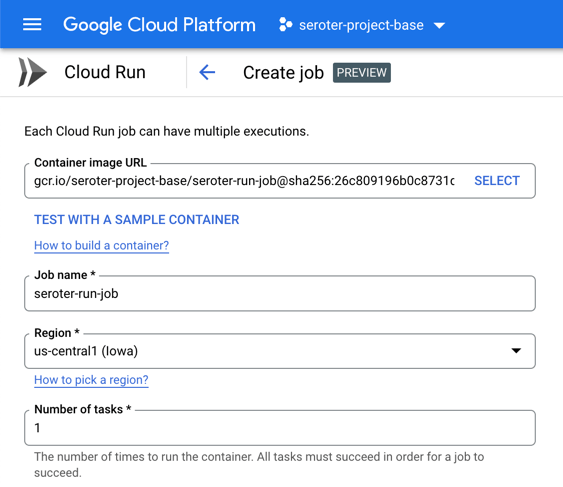

Let’s go back into the Cloud Run interface, where we just turned on a UI for creating and managing jobs. I start by choosing my just-now-created container image and keeping the “number of tasks” to 1.

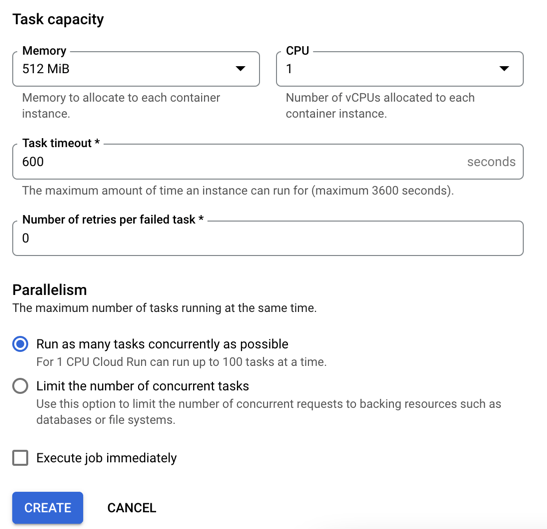

For reference, there are other fun “job” settings. I can allocate up to 32GB of memory and 8 vCPUs. I can set the timeout (up to an hour), choose how much parallelism I want, and even select the option to run the job right away.

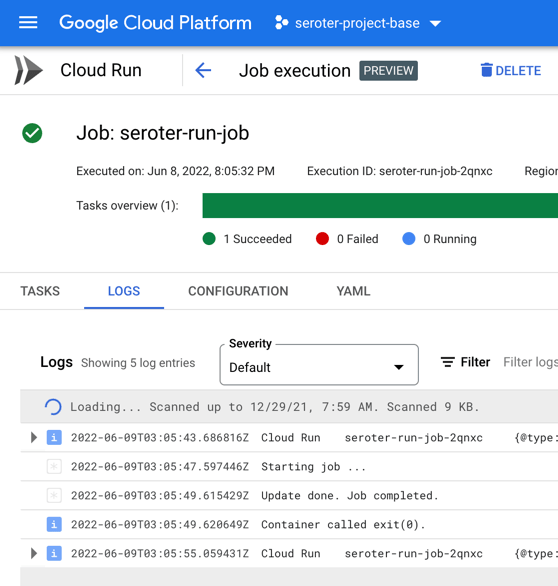

After creating the job, I click the button that says “execute” and run my job. I see job status and application logs, updated live. My job succeeded!

Checking Cloud Spanner confirms that my all table rows were updated to a status of “SHIPPED”.

It’s great that I didn’t have to leave the Cloud Run API or interface to build this batch processor. Super convenient!

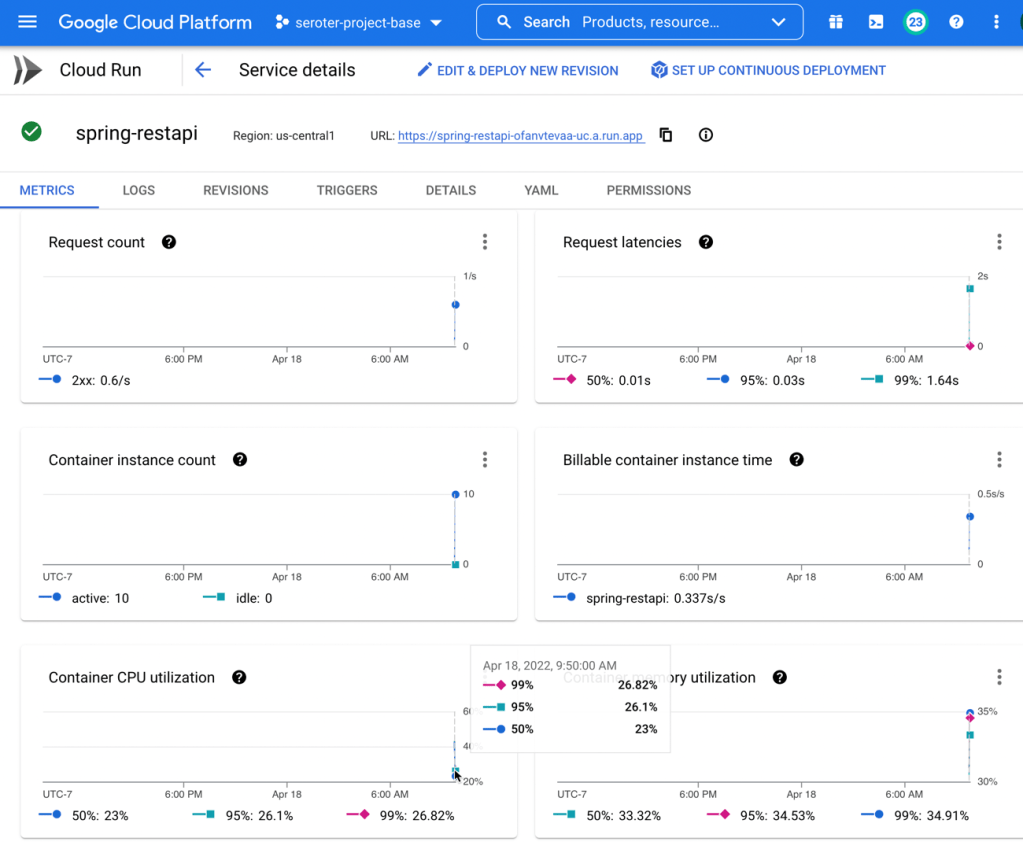

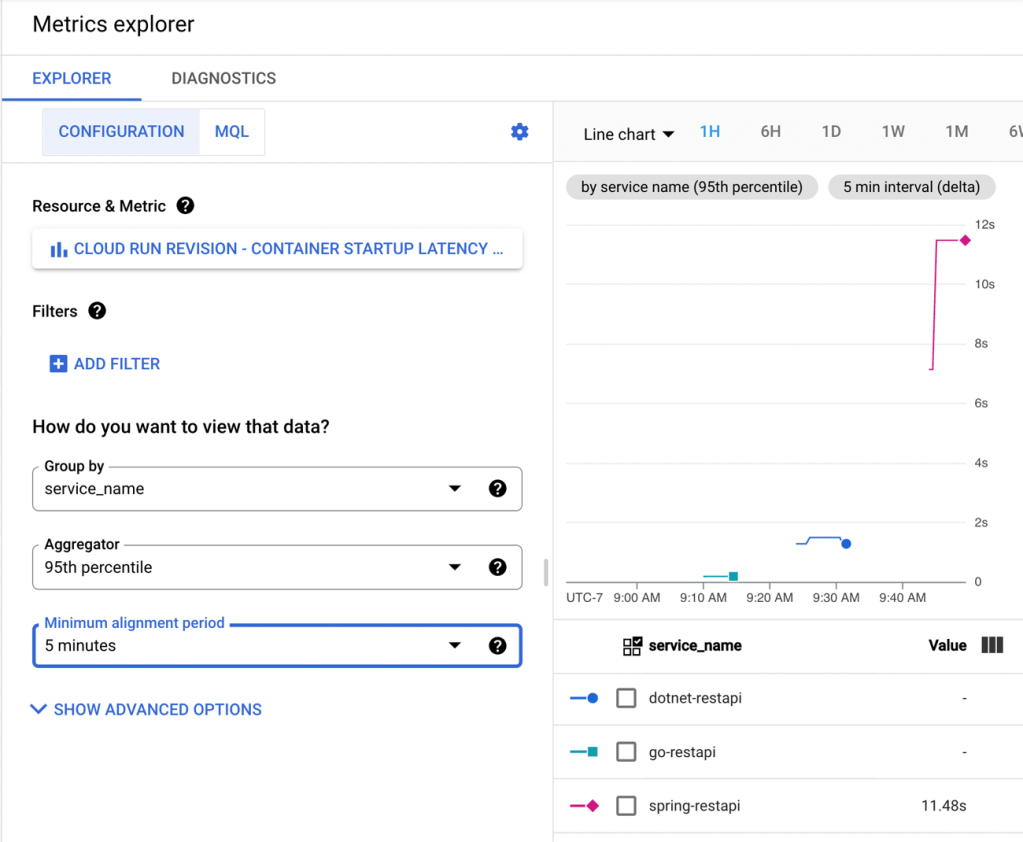

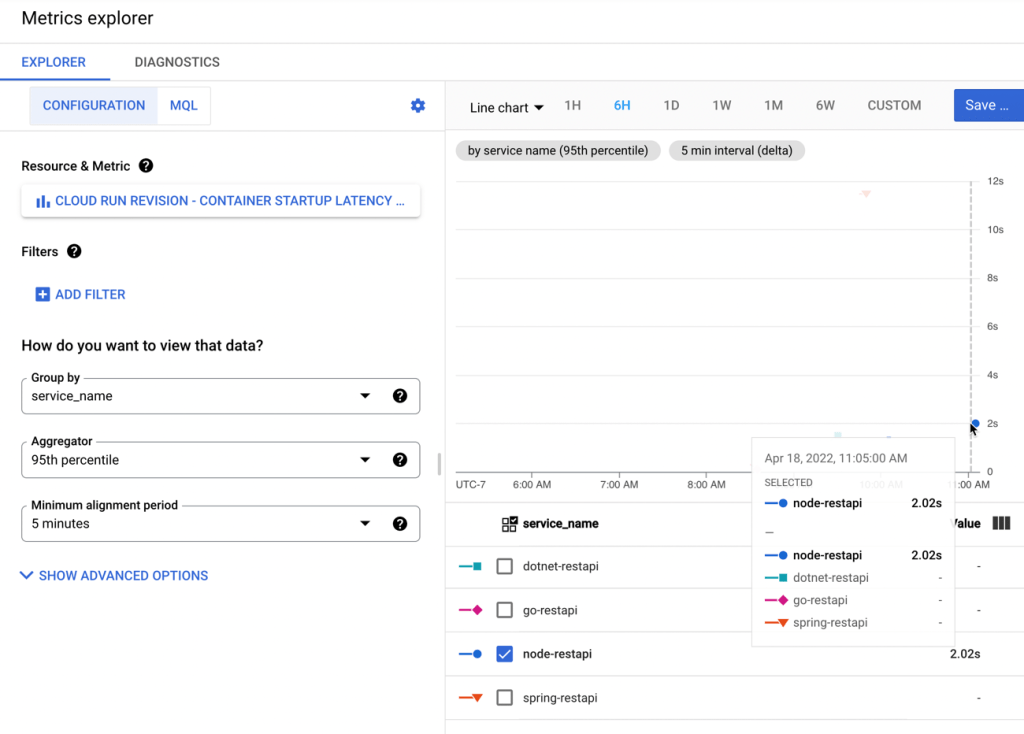

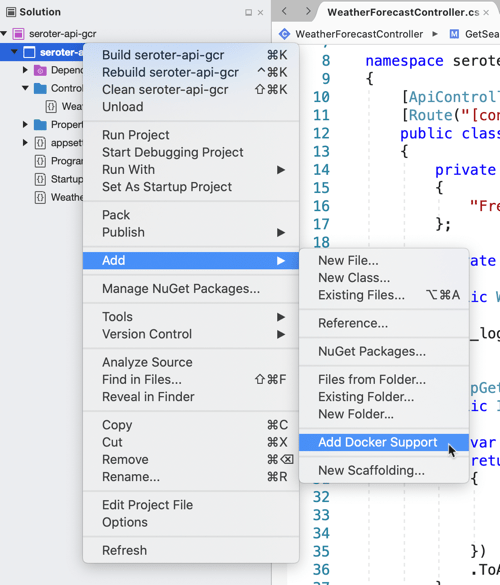

Creating the queue listener in Spring and deploying to Cloud Run

The final piece of our architecture requires a queue listener. When our delivery drivers drop off a package, their system sends a message to Google Cloud Pub/Sub, our pretty remarkable messaging system. To be sure, I could trigger Cloud Run (or Cloud Functions) automatically whenever a message hits Pub/Sub. That’s a built-in capability. I don’t need to use a processor that directly pulls from the queue.

But maybe I want to control the pull from the queue. I could do stateful processing over a series of messages, or pull batches instead of one-at-a-time. Here, I’m going to use Spring Cloud Stream which talks to any major messaging system and triggers a function whenever a message arrives.

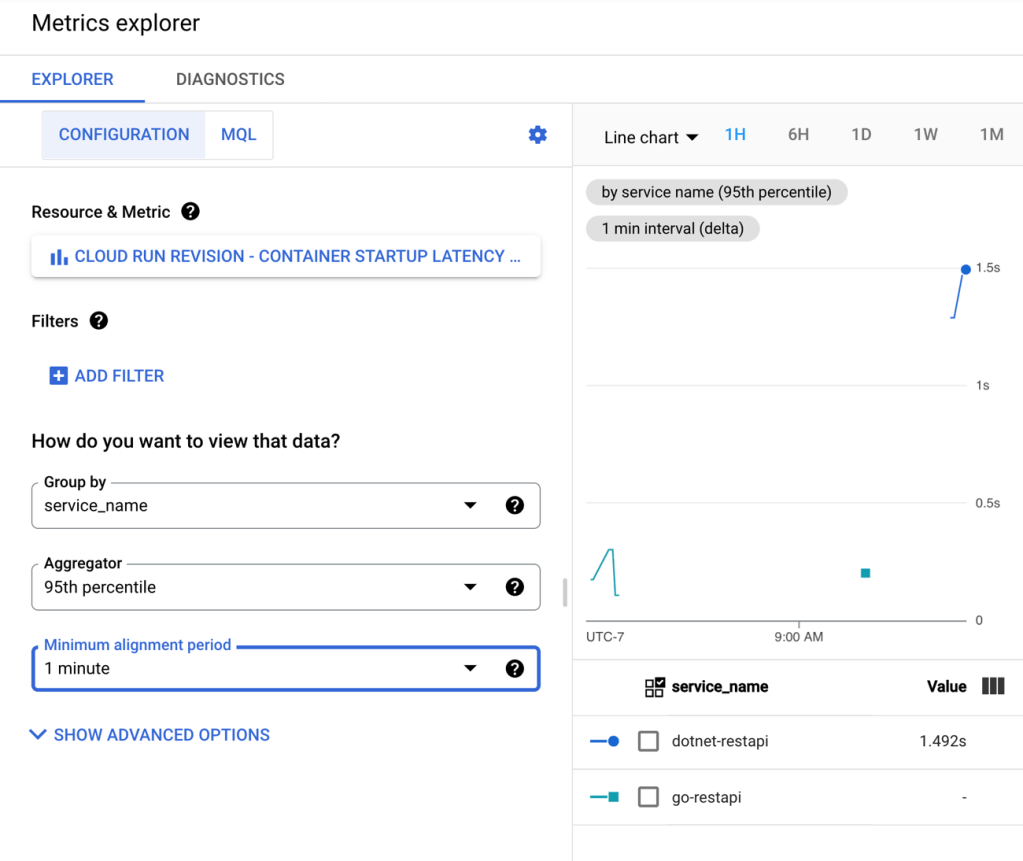

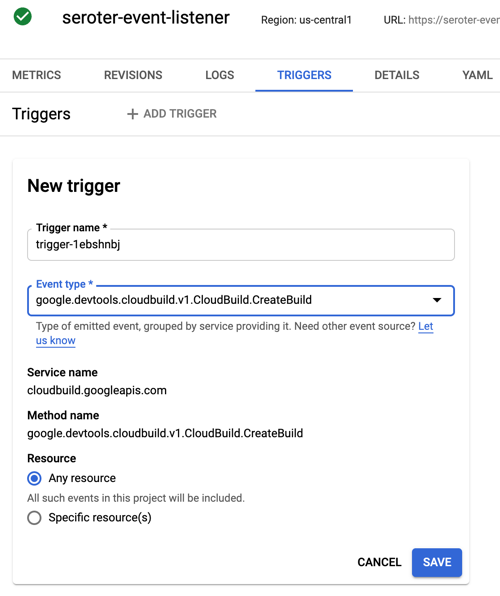

Also note that Cloud Run doesn’t explicitly support this worker pattern, but you can make it work fairly easily. I’ll show you.

I went to start.spring.io and configured my app by choosing a Spring Web and GCP Support dependency. Why “web” if this is a background worker? Cloud Run still expects a workload that binds to a web port, so we’ll embed a web server that’s never used.

After generating the project and opening it, I deleted the “GCP support” dependency (I just wanted an auto-generated dependency management value) and added a couple of POM dependencies that my app needs. The first is the Google Cloud Pub/Sub “binder” for Spring Cloud Stream, and the second is the JDBC driver for Cloud Spanner.

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-gcp-pubsub-stream-binder</artifactId>

<version>1.2.8.RELEASE</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>com.google.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>google-cloud-spanner-jdbc</artifactId>

</dependency>

I then created an object definition for “Order” with the necessary fields and getters/setters. Let’s review the primary class that does all the work. The way Spring Cloud Stream works is that reactive functions annotated as beans are invoked when a message comes in. The Spring machinery wires up the connection to the message broker and does most of the work. In this case, when I get an order message, I update the order status in Cloud Spanner to “DELIVERED.”

package com.seroter.runworker;

import java.util.function.Consumer;

import org.springframework.boot.SpringApplication;

import org.springframework.boot.autoconfigure.SpringBootApplication;

import org.springframework.context.annotation.Bean;

import reactor.core.publisher.Flux;

import java.sql.Connection;

import java.sql.DriverManager;

import java.sql.Statement;

import java.sql.SQLException;

@SpringBootApplication

public class RunWorkerApplication {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(RunWorkerApplication.class, args);

}

//takes in a Flux (stream) of orders

@Bean

public Consumer<Flux<Order>> reactiveReadOrders() {

//connection to my database

String connectionUrl = "jdbc:cloudspanner:/projects/seroter-project-base/instances/seroter-spanner/databases/seroterdb";

return value ->

value.subscribe(v -> {

try (Connection c = DriverManager.getConnection(connectionUrl); Statement statement = c.createStatement()) {

String command = "UPDATE Orders SET Status = 'DELIVERED' WHERE OrderId = " + v.getOrderId().toString();

statement.executeUpdate(command);

} catch (SQLException e) {

System.out.println(e.toString());

}

});

}

}

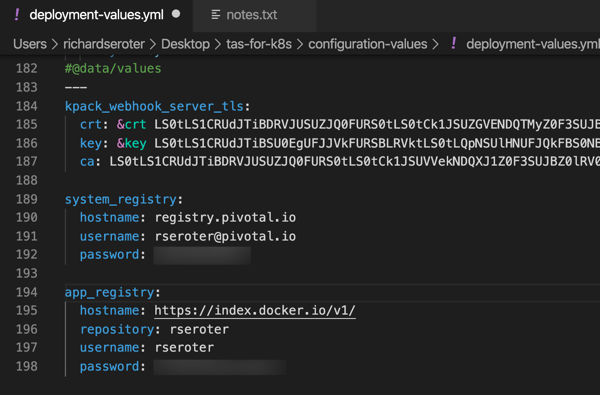

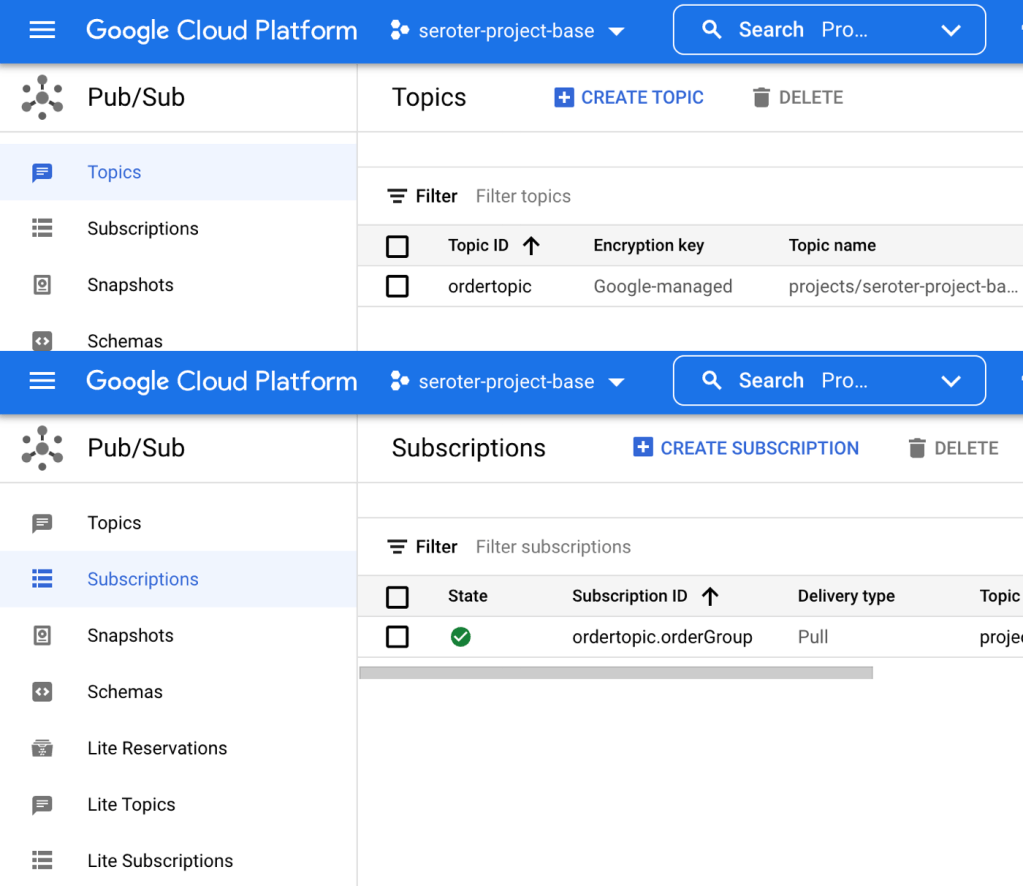

My corresponding properties file has the few values Spring Cloud Stream needs to know about. Specifically, I’m specifying the Pub/Sub topic, indicating that I can take in batches of data, and setting the “group” which corresponds to the topic subscription. What’s cool is that if these topics and subscriptions don’t exist already, Spring Cloud Stream creates them for me.

server.port=8080

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.reactiveReadOrders-in-0.destination=ordertopic

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.reactiveReadOrders-in-0.consumer.batch-mode=true

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.reactiveReadOrders-in-0.content-type=application/json

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.reactiveReadOrders-in-0.group=orderGroup

For the final time, I run the Cloud Build command to build and package my Java app into a container image: gcloud builds submit --pack image=gcr.io/seroter-project-base/seroter-run-worker

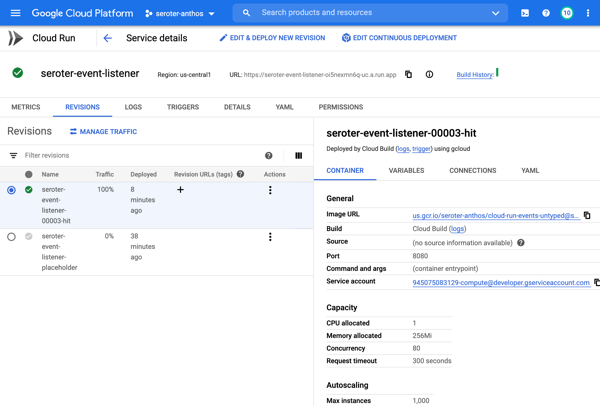

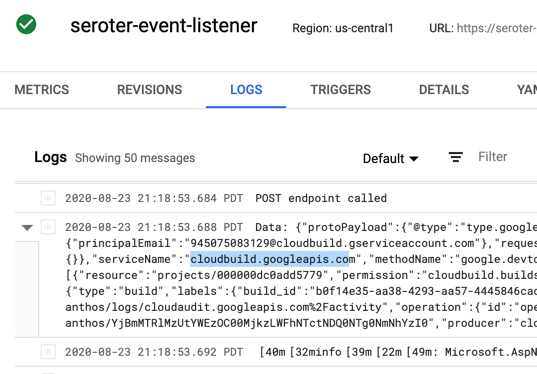

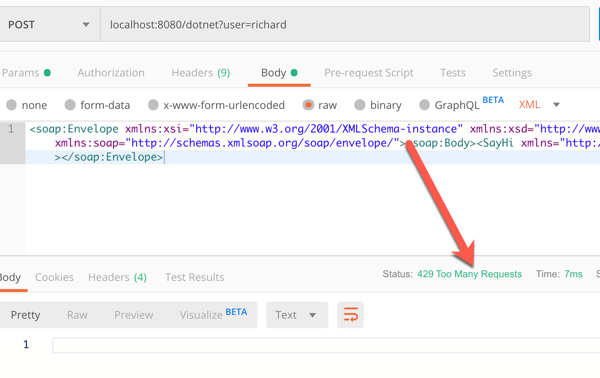

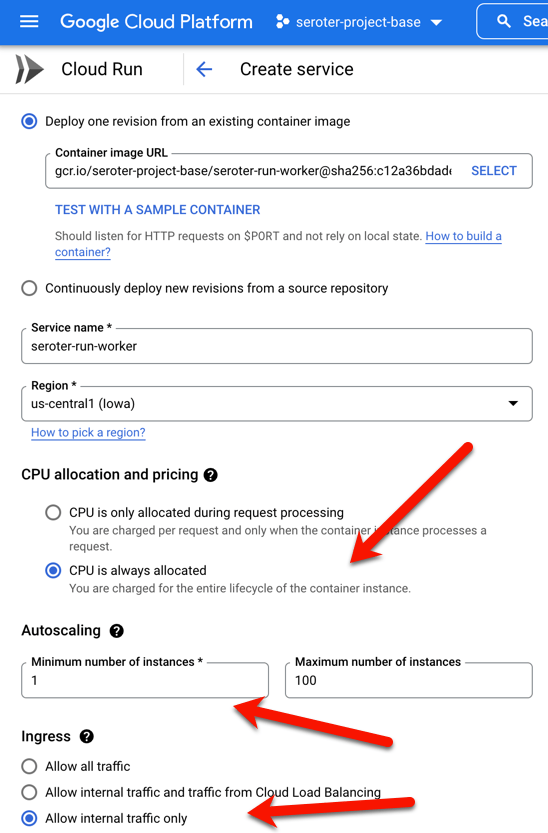

With this container image ready to go, I slide back to the Cloud Run UI and create a new service instance. This time, after choosing my image, I choose “always allocated CPU” to ensure that the CPU stays on the whole time. And I picked a minimum instance of one so that I have a single always-on worker pulling from Pub/Sub. I also chose “internal only” traffic and require authentication to make this harder for someone to randomly invoke.

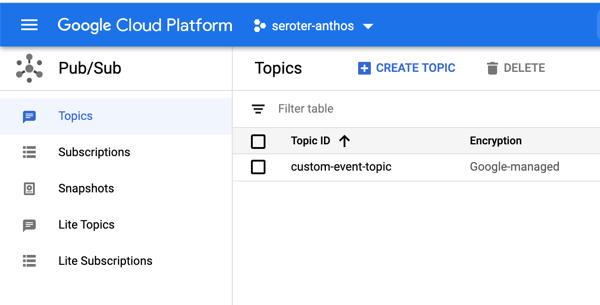

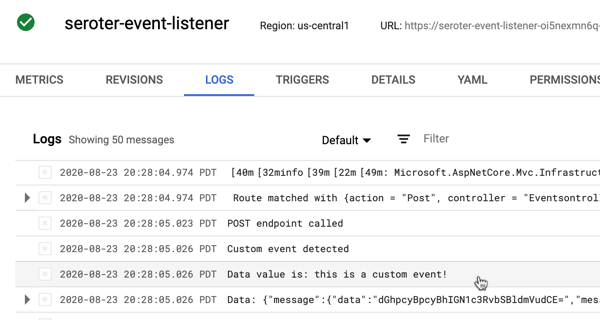

My service quickly starts up, and upon initialization, creates both the topic and queue for my app.

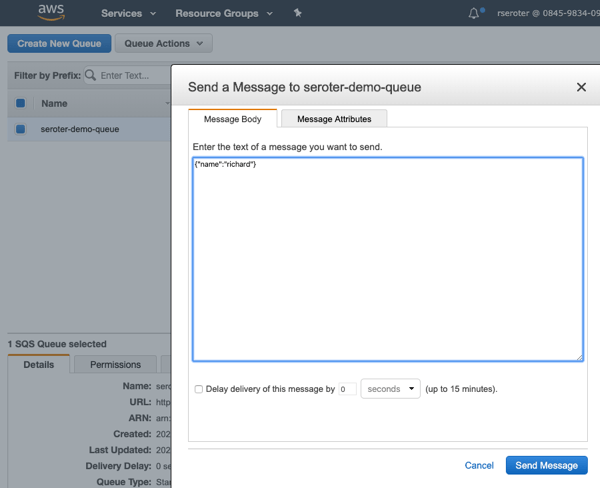

I go into the Pub/Sub UI where I can send a message directly into a topic. All I need to send in is a JSON payload that holds the order ID of the record to update.

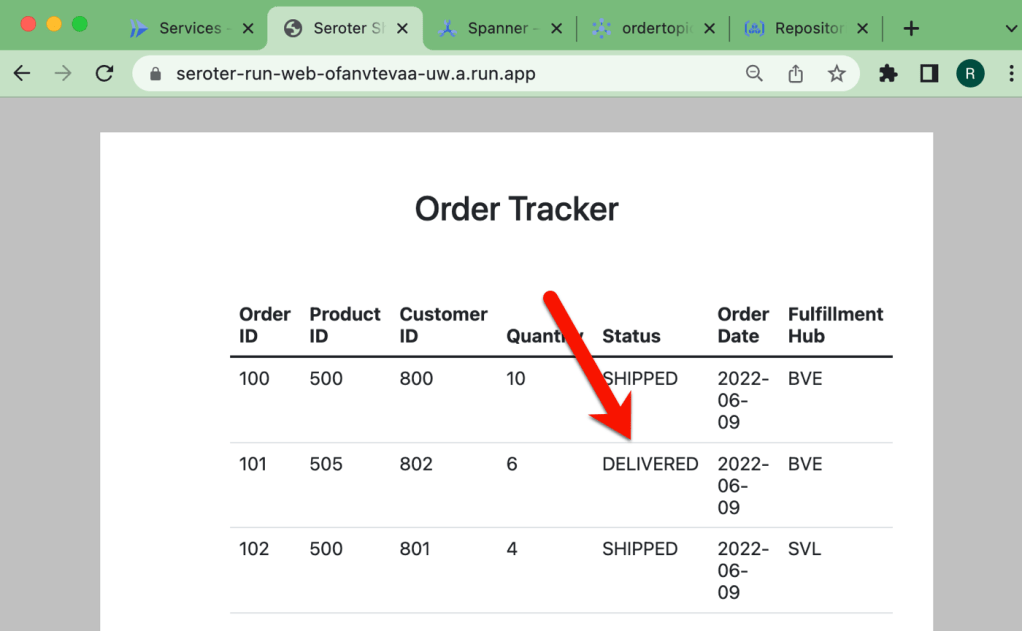

The result? My database record is updated, and I see this by viewing my web application and noticing the second row has a new “status” value.

Wrap up

Instead of using two or three distinct cloud compute services to satisfy this architecture, I used one. Cloud Run defies your expectations of what serverless can be, especially now that you can run serverless jobs or even continuously-running apps. In all cases, I have no infrastructure to provision, scale, or manage.

You can use Cloud Run, Pub/Sub, and Cloud Build with our generous free tier, and Spanner has never been cheaper to try out. Give it a whirl, and tell me what you think of Cloud Run jobs.