You’ve got microservices. Great. They’re being continuous delivered. Neato. Ok … now what? The next hurdle you may face is data processing amongst this distributed mesh o’ things. Brokered messaging engines like Azure Service Bus or RabbitMQ are nice choices if you want pub/sub routing and smarts residing inside the broker. Lately, many folks have gotten excited by stateful stream processing scenarios and using distributed logs as a shared source of events. In those cases, you use something like Apache Kafka or Azure Event Hubs and rely on smart(er) clients to figure out what to read and what to process. What should you use to build these smart stream processing clients?

I’ve written about Spring Cloud Stream a handful of times, and last year showed how to integrate with the Kafka interface on Azure Event Hubs. Just today, Microsoft shipped a brand new “binder” for Spring Cloud Stream that works directly with Azure Event Hubs. Event processing engines aren’t useful if you aren’t actually publishing or subscribing to events, so I thought I’d try out this new binder and see how to light up Azure Event Hubs.

Setting Up Microsoft Azure

First, I created a new Azure Storage account. When reading from an Event Hubs partition, the client maintains a cursor. This cursor tells the client where it should start reading data from. You have the option to store this cursor server-side in an Azure Storage account so that when your app restarts, you can pick up where you left off.

There’s no need for me to create anything in the Storage account, as the Spring Cloud Stream binder can handle that for me.

Next, the actual Azure Event Hubs account! First I created the namespace. Here, I chose things like a name, region, pricing tier, and throughput units.

Like with the Storage account, I could stop here. My application will automatically create the actual Event Hub if it doesn’t exist. In reality, I’d probably want to create it first so that I could pre-define things like partition count and message retention period.

Creating the event publisher

The event publisher takes in a message via web request, and publishes that message for others to process. The app is a Spring Boot app, and I used the start.spring.io experience baked into Spring Tools (for Eclipse, Atom, and VS Code) to instantiate my project. Note that I chose “web” and “cloud stream” dependencies.

With the project created, I added the Event Hubs binder to my project. In the pom.xml file, I added a reference to the Maven package.

<dependency>

<groupId>com.microsoft.azure</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-azure-eventhubs-stream-binder</artifactId>

<version>1.1.0.RC5</version>

</dependency>

Now before going much farther, I needed a credentials file. Basically, it includes all the info needed for the binder to successfully chat with Azure Event Hubs. You use the az CLI tool to generate it. If you don’t have it handy, the easiest option is to use the Cloud Shell built into the Azure Portal.

From here, I did az list to show all my Azure subscriptions. I chose the one that holds my Azure Event Hub and copied the associated GUID. Then, I set that account as my default one for the CLI with this command:

az account set -s 11111111-1111-1111-1111-111111111111

With that done, I issued another command to generate the credential file.

az ad sp create-for-rbac --sdk-auth > my.azureauth

I opened up that file within the Cloud Shell, copied the contents, and pasted the JSON content into a new file in the resources directory of my Spring Boot app.

Next up, the code. Because we’re using Spring Cloud Stream, there’s no specific Event Hubs logic in my code itself. I only use Spring Cloud Stream concepts, which abstracts away any boilerplate configuration and setup. The code below shows a simple REST controller that takes in a message, and publishes that message to the output channel. Behind the scenes, when my app starts up, Boot discovers and inflates all the objects needed to securely talk to Azure Event Hubs.

@EnableBinding(Source.class)

@RestController

@SpringBootApplication

public class SpringStreamEventhubsProducerApplication {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(SpringStreamEventhubsProducerApplication.class, args);

}

@Autowired

private Source source;

@PostMapping("/messages")

public String postMsg(@RequestBody String msg) {

this.source.output().send(new GenericMessage<>(msg));

return msg;

}

}

How simple is that? All that’s left is the application properties used by the app. Here, I set a few general Spring Cloud Stream properties, and a few related to the Event Hubs binder.

#point to credentials

spring.cloud.azure.credential-file-path=my.azureauth

#get these values from the Azure Portal

spring.cloud.azure.resource-group=demos

spring.cloud.azure.region=East US

spring.cloud.azure.eventhub.namespace=seroter-event-hub

#choose where to store checkpoints

spring.cloud.azure.eventhub.checkpoint-storage-account=serotereventhubs

#set the name of the Event Hub

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.output.destination=seroterhub

#be lazy and let the app create the Storage blobs and Event Hub

spring.cloud.azure.auto-create-resources=true

With that, I had a working publisher.

Creating the event subscriber

It’s no fun publishing messages if no one ever reads them. So, I built a subscriber. I walked through the same start.spring.io experience as above, this time ONLY choosing the Cloud Stream dependency. And then added the Event Hubs binder to the pom.xml file of the created project. I also copied the my.azureauth file (containing our credentials) from the publisher project to the subscriber project.

It’s criminally simple to pull messages from a broker using Spring Cloud Stream. Here’s the full extent of the code. Stream handles things like content type transformation, and so much more.

@EnableBinding(Sink.class)

@SpringBootApplication

public class SpringStreamEventhubsConsumerApplication {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(SpringStreamEventhubsConsumerApplication.class, args);

}

@StreamListener(Sink.INPUT)

public void handleMessage(String msg) {

System.out.println("message is " + msg);

}

}

The final step involved defining the application properties, including the Storage account for checkpointing, and whether to automatically create the Azure resources.

#point to credentials

spring.cloud.azure.credential-file-path=my.azureauth

#get these values from the Azure Portal

spring.cloud.azure.resource-group=demos

spring.cloud.azure.region=East US

spring.cloud.azure.eventhub.namespace=seroter-event-hub

#choose where to store checkpoints

spring.cloud.azure.eventhub.checkpoint-storage-account=serotereventhubs

#set the name of the Event Hub

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.input.destination=seroterhub

#set the consumer group

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.input.group=system3

#read from the earliest point in the log; default val is LATEST

spring.cloud.stream.eventhub.bindings.input.consumer.start-position=EARLIEST

#be lazy and let the app create the Storage blobs and Event Hub

spring.cloud.azure.auto-create-resources=true

And now we have a working subscriber.

Testing this thing

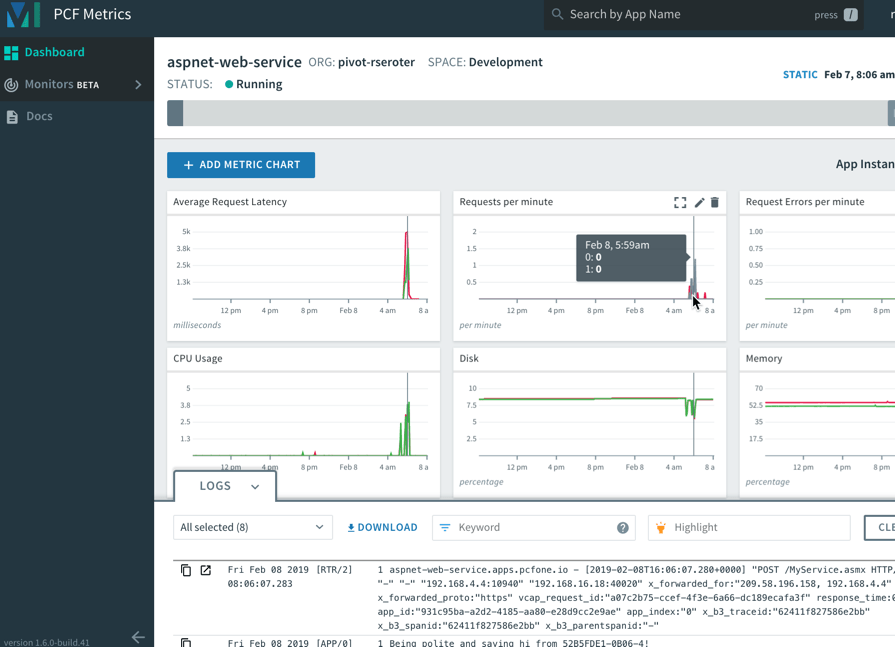

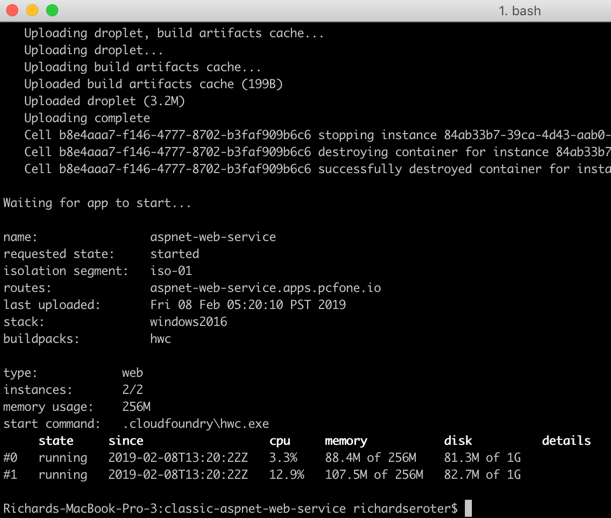

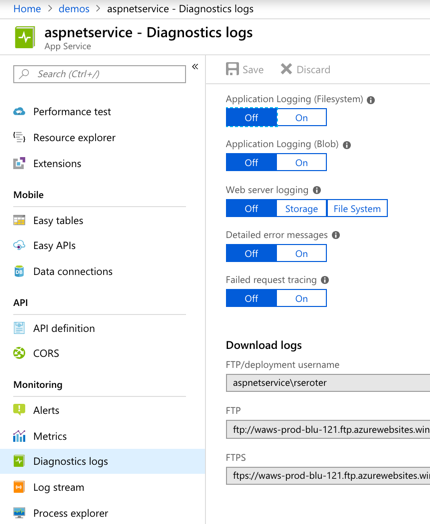

First, I started up the producer app. It started up successfully, and I can see in the startup log that it created the Event Hub automatically for me after connecting.

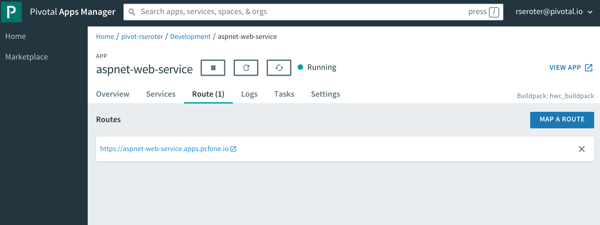

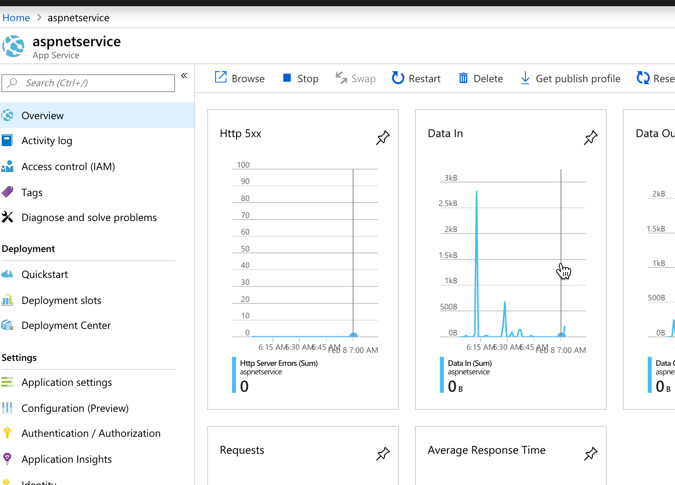

To be sure, I checked the Azure Portal and saw a new Event Hub with 4 partitions.

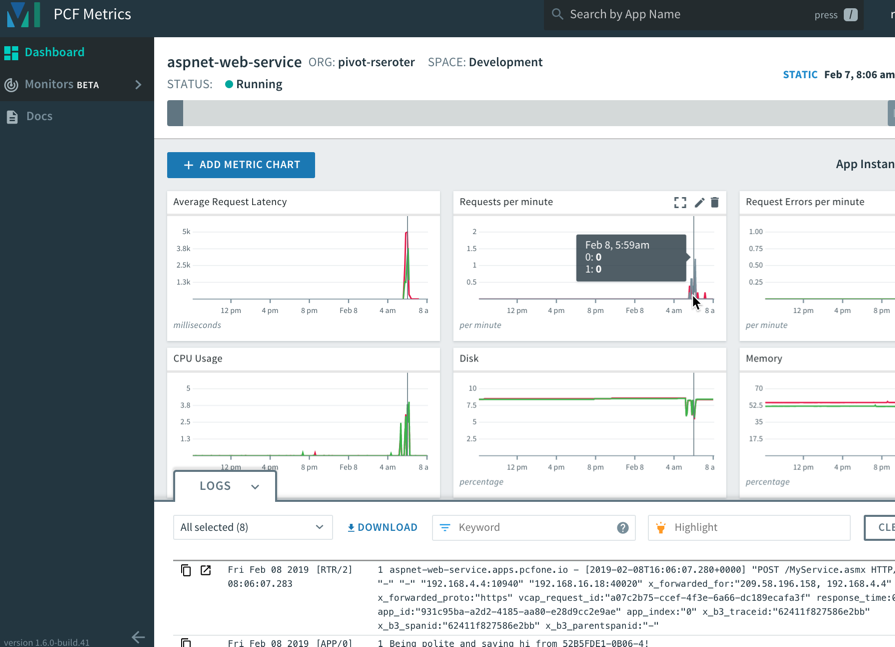

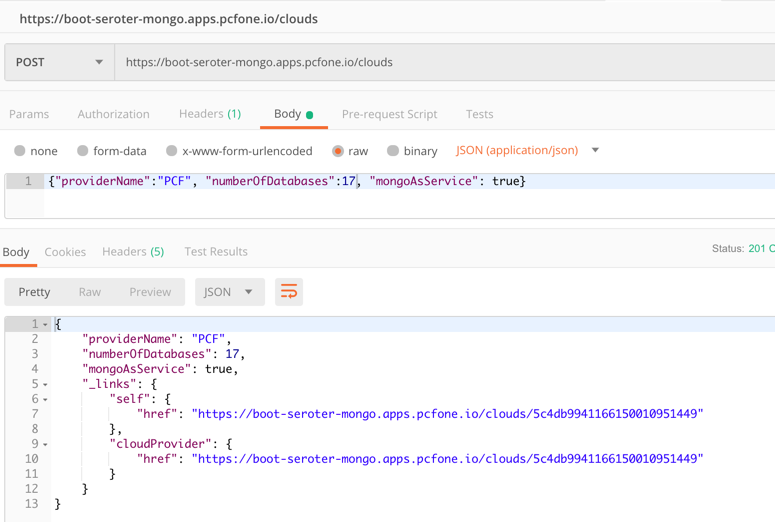

Sweet. I called the REST endpoint on my app three times to get a few messages into the Event Hub.

Now remember, since we’re dealing with a log versus a queuing system, my consumers don’t have to be online (or even registered anywhere) to get the data at their leisure. I can attach to the log at any time and start reading it. So that data is just hanging out in Event Hubs until its retention period expires.

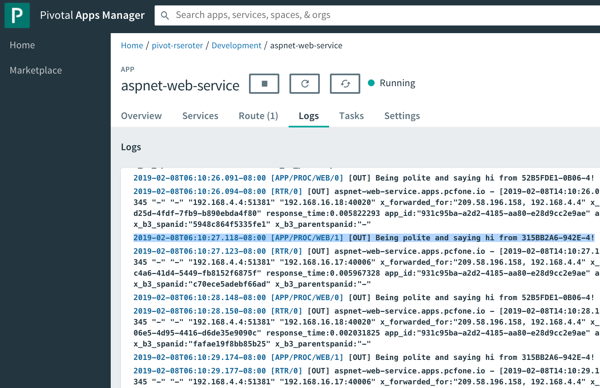

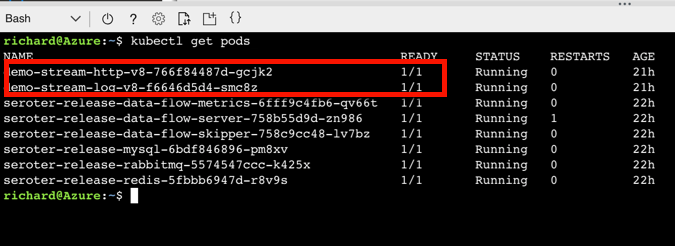

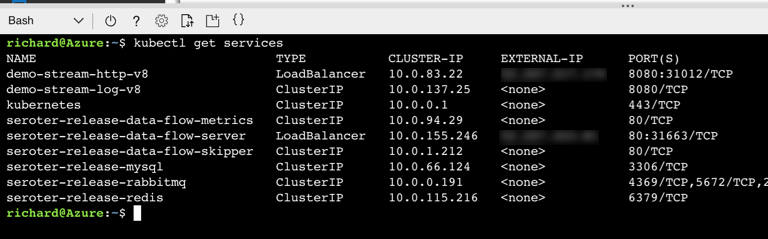

I started up my Spring Boot subscriber app. After a couple moments, it connected to Azure Event Hubs, and read the three entries that it hadn’t ever seen before.

Back in the Azure Portal, I checked and saw a new blob container in my Storage account, with a folder for my consumer group, and checkpoints for each partition.

If I sent more messages into the REST endpoint, they immediately appeared in my subscriber app. What if I defined a new consumer group? Would it read all the messages from the beginning?

I stopped the subscriber app, changed the application property for “consumer group” to “system4” and restarted the app. After Spring Cloud Stream connected to each partition, it pumped out whatever it found, and responded immediately to any new entries.

Whether you’re building a change-feed listener off of Cosmos DB, sharing data between business partners, or doing data processing between microservices, you’ll probably be using a broker. If it’s an event bus like Azure Event Hubs, you now have an easy path with Spring Cloud Stream.