It’s a gift to the world that no one pays me to write software any longer. You’re welcome. But I still enjoy coding and trying out a wide variety of things. Given that I rarely have hours upon hours to focus on writing software, I seek things that make me more productive with the time I have. My inner development loop matters. You know, the iterative steps we perform to write, build, test, and commit code.

So let’s say I want to build a REST API in Java. This REST API stores and returns the names of television characters. What’s the bare minimum that I need to get going?

- An IDE or code editor

- A database to store records

- A web server to host the app

- A route to reach the app

What are things I personally don’t want to deal with, especially if I’m experimenting and learning quickly?

- Provisioning lots of infrastructure. Either locally to emulate the target platform, or elsewhere to actually run my app. It takes time, and I don’t know what I need.

- Creating database stubs or mocks, or even configuring Docker containers to stand-in for my database. I want the real thing, if possible.

- Finding a container registry to use. All this stuff just needs to be there.

- Writing Dockerfiles to package an app. I usually get them wrong.

- Configuring API gateways or network routing rules. Just give me an endpoint.

Based on this, one of the quickest inner loop I know of involves Spring Boot, the Google Cloud SDK, Cloud Firestore, and Google Cloud Run. Spring Boot makes it easy to spin up API projects and it’s ORM capabilities make it simple to interact with a database. Speaking of databases, Cloud Firestore is powerful and doesn’t force me into a schema. That’s great when I don’t know the final state of my data structure. And Cloud Run seems like the single best way to run custom-built apps in the cloud. How about we run through this together?

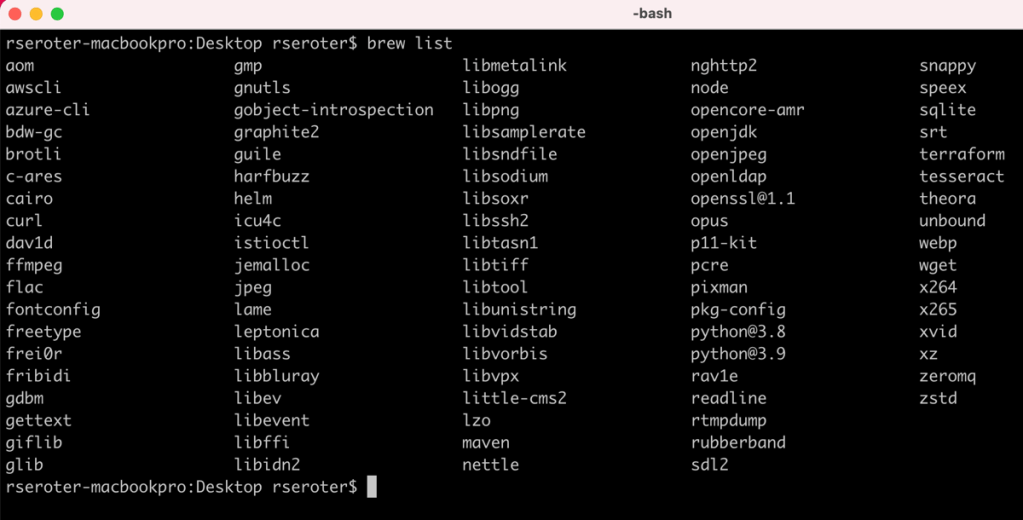

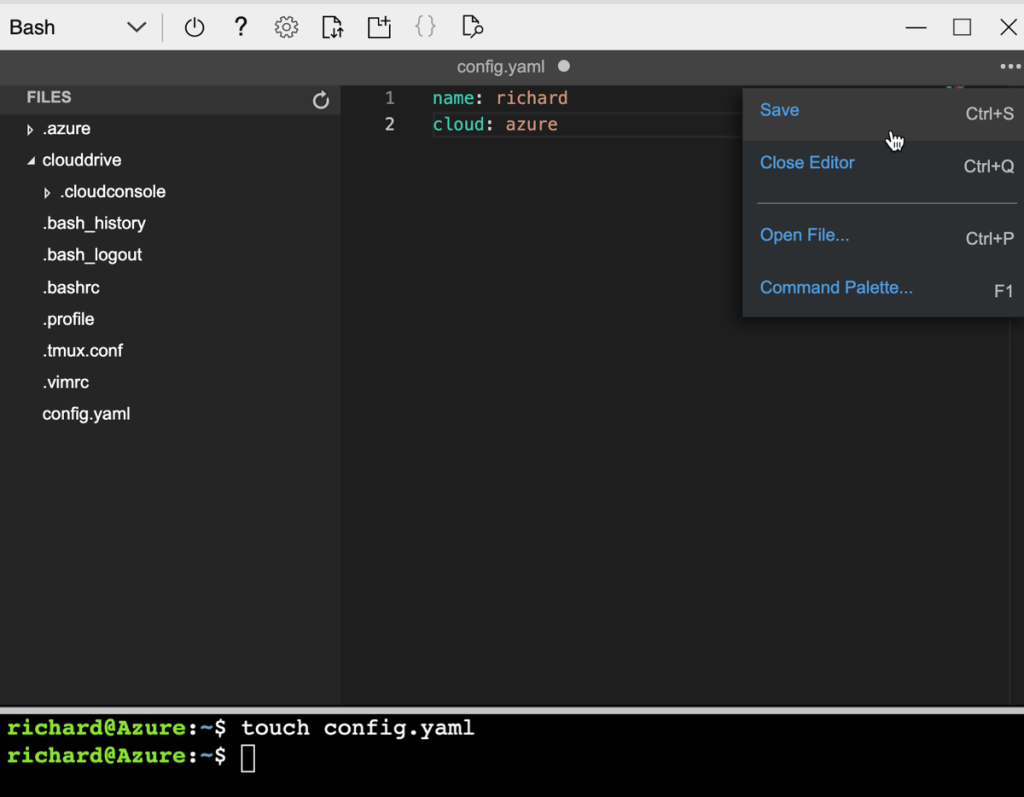

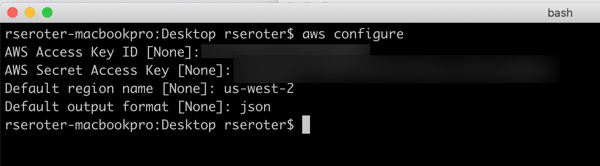

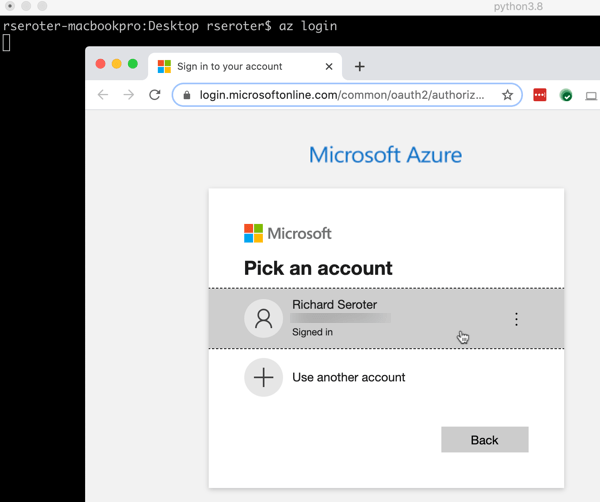

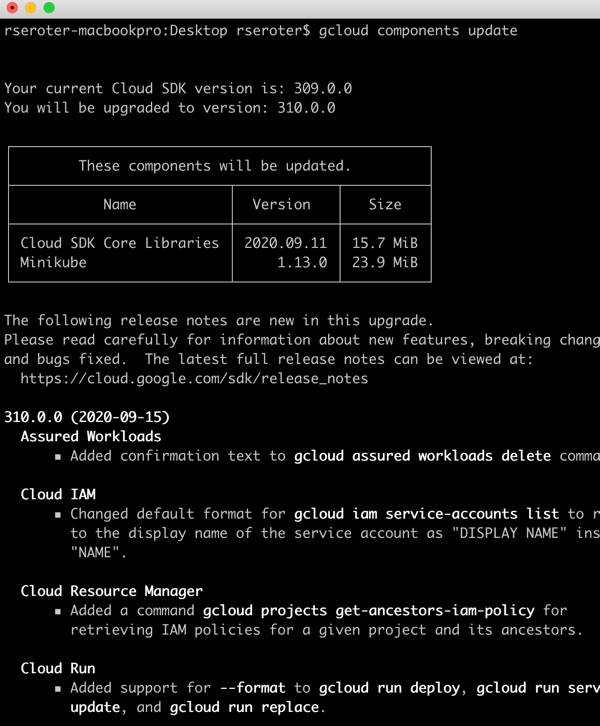

On my local machine, I’ve installed Visual Studio Code—the FASTEST possible inner loop might have involved using the Google Cloud Shell and skipping any local work, but I still like doing local dev—along with the latest version of Java, and the Google Cloud SDK. The SDK comes with lots of CLI tools and emulators, including one for Firestore and Datastore (an alternate API).

Time to get to work. I visited start.spring.io to generate a project. I could choose a few dependencies from the curated list, including a default one for Google Cloud services, and another for exposing my data repository as a series of REST endpoints.

I generated the project, and opened it in Visual Studio Code. Then, I opened the pom.xml file and added one more dependency. While I’m using the Firestore database, I’m using it in “Datastore mode” which works better with Spring Data REST. Here’s my finished pom file.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<project xmlns="http://maven.apache.org/POM/4.0.0" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://maven.apache.org/POM/4.0.0 https://maven.apache.org/xsd/maven-4.0.0.xsd">

<modelVersion>4.0.0</modelVersion>

<parent>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-parent</artifactId>

<version>2.4.4</version>

<relativePath/> <!-- lookup parent from repository -->

</parent>

<groupId>com.seroter</groupId>

<artifactId>boot-gcp-run-firestore</artifactId>

<version>0.0.1-SNAPSHOT</version>

<name>boot-gcp-run-firestore</name>

<description>Demo project for Google Cloud and Spring Boot</description>

<properties>

<java.version>11</java.version>

<spring-cloud-gcp.version>2.0.0</spring-cloud-gcp.version>

<spring-cloud.version>2020.0.2</spring-cloud.version>

</properties>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-data-rest</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>com.google.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-gcp-starter</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>com.google.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-gcp-starter-data-datastore</artifactId>

<version>2.0.2</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-test</artifactId>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

<dependencyManagement>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-dependencies</artifactId>

<version>${spring-cloud.version}</version>

<type>pom</type>

<scope>import</scope>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>com.google.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-gcp-dependencies</artifactId>

<version>${spring-cloud-gcp.version}</version>

<type>pom</type>

<scope>import</scope>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

</dependencyManagement>

<build>

<plugins>

<plugin>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-maven-plugin</artifactId>

</plugin>

</plugins>

</build>

</project>

Let’s sling a little code, shall we? Spring Boot almost makes this too easy. First, I created a class to describe a “character.” I started with just a couple of characteristics—full name, and role.

package com.seroter.bootgcprunfirestore;

import com.google.cloud.spring.data.datastore.core.mapping.Entity;

import org.springframework.data.annotation.Id;

@Entity

class Character {

@Id

private Long id;

private String FullName;

private String Role;

public String getFullName() {

return FullName;

}

public String getRole() {

return Role;

}

public void setRole(String role) {

this.Role = role;

}

public void setFullName(String fullName) {

this.FullName = fullName;

}

}

All that’s left is to create a repository resource and Spring Data handles the rest. Literally!

package com.seroter.bootgcprunfirestore;

import com.google.cloud.spring.data.datastore.repository.DatastoreRepository;

import org.springframework.data.rest.core.annotation.RepositoryRestResource;

@RepositoryRestResource

interface CharacterRepository extends DatastoreRepository<Character, Long> {

}

That’s kinda it. No other code is needed. Now I want to test it out and see if it works. The first option is to spin up an instance of the Datastore emulator—not Firestore since I’m using the Datastore API—when my app starts. That’s handy. It’s one line in my app.properties file.

spring.cloud.gcp.datastore.emulator.enabled=true

When I execute ./mvnw spring-boot:run I see the app compile, and get a notice that the Datastore emulator was started up. I went to Postman to call the API. First I added a record.

Then I called the endpoint to retrieve the store data. It worked. It’s great that Spring Data REST wires up all these endpoints automatically.

Now, I really like that I can start up the emulator as part of the build. But, that instance is ephemeral. When I stop running the app locally, my instance goes away. What if my inner loop involves constantly stopping the app to make changes, recompile, and start up again? Don’t worry. It’s also easy to stand up the emulator by itself, and attach my app to it. First, I ran gcloud beta emulators datastore start to get the local instance running in about 2 seconds.

Then I updated my app.properties file by commenting out the statement that enables local emulation, and replacing with this statement that points to the emulator:

spring.cloud.gcp.datastore.host=localhost:8081

Now I can start and stop the app as much as I want, and the data persists. Both options are great, depending on how you’re doing local development.

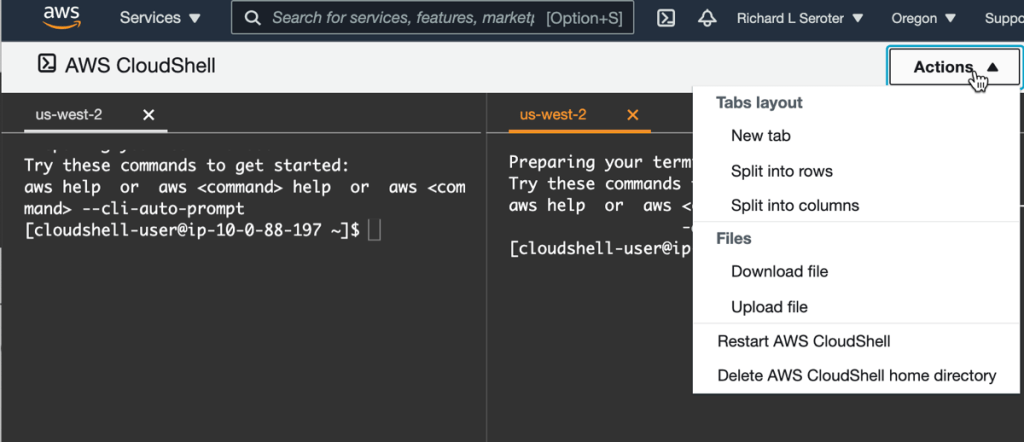

Let’s deploy. I wanted to see this really running, and iterate further after I’m confident in how it behaves in a production-like environment. The easiest option for any Spring Boot developer is Cloud Run. It’s quick, it’s serverless, and we support buildpacks, so you never need to see a container.

I issued a single CLI command—gcloud beta run deploy boot-app --memory=1024 --source .— to package up my app and get it to Cloud Run.

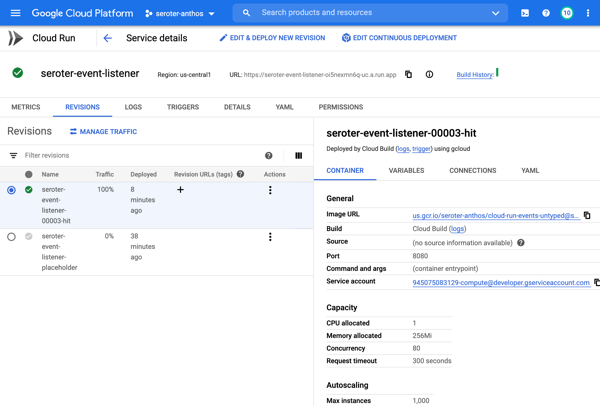

After a few moments, I had a container in the registry, and an instance of Cloud Run. I don’t have to do any other funny business to reach the endpoint. No gateways, proxies, or whatever. And everything is instantly wired up to Cloud Logging and Cloud Monitoring for any troubleshooting. And I can provision up to 8GB of RAM and 4 CPUs, while setting up to 250 concurrent connections per container, and 1000 maximum instances. There’s a lot you can run with that horsepower.

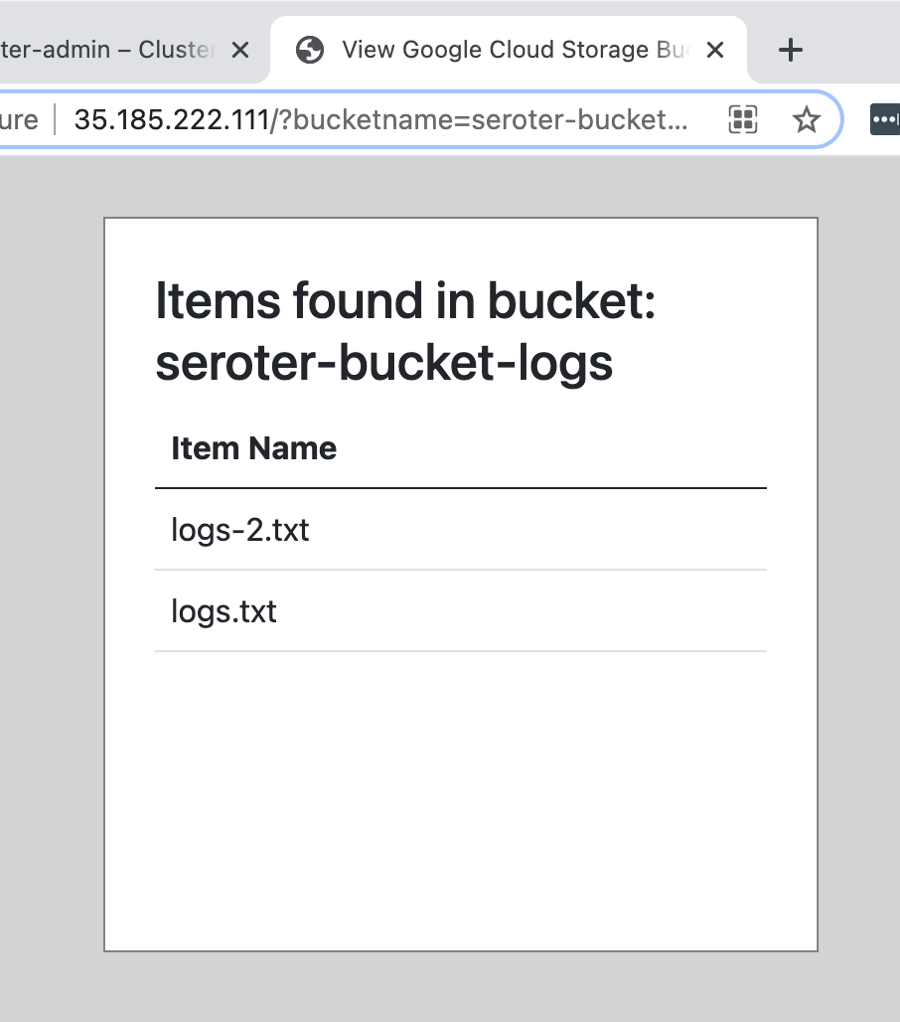

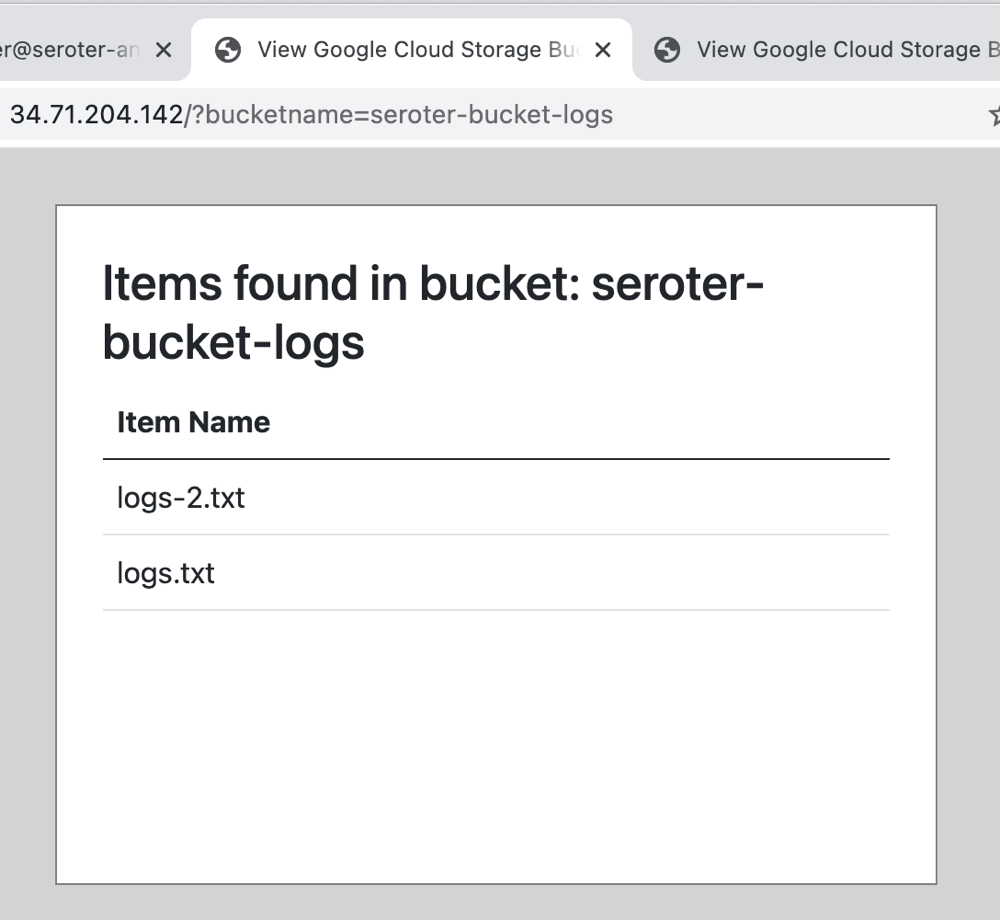

I pinged the public endpoint, and sure enough, it was easy to publish and retrieve data from my REST API …

… and see the data sitting in the database!

When I saw the results, I realized I wanted more data fields in here. No problem. I went back to my Spring Boot app, and added a new field, isHuman. There are lots of animals on my favorite shows.

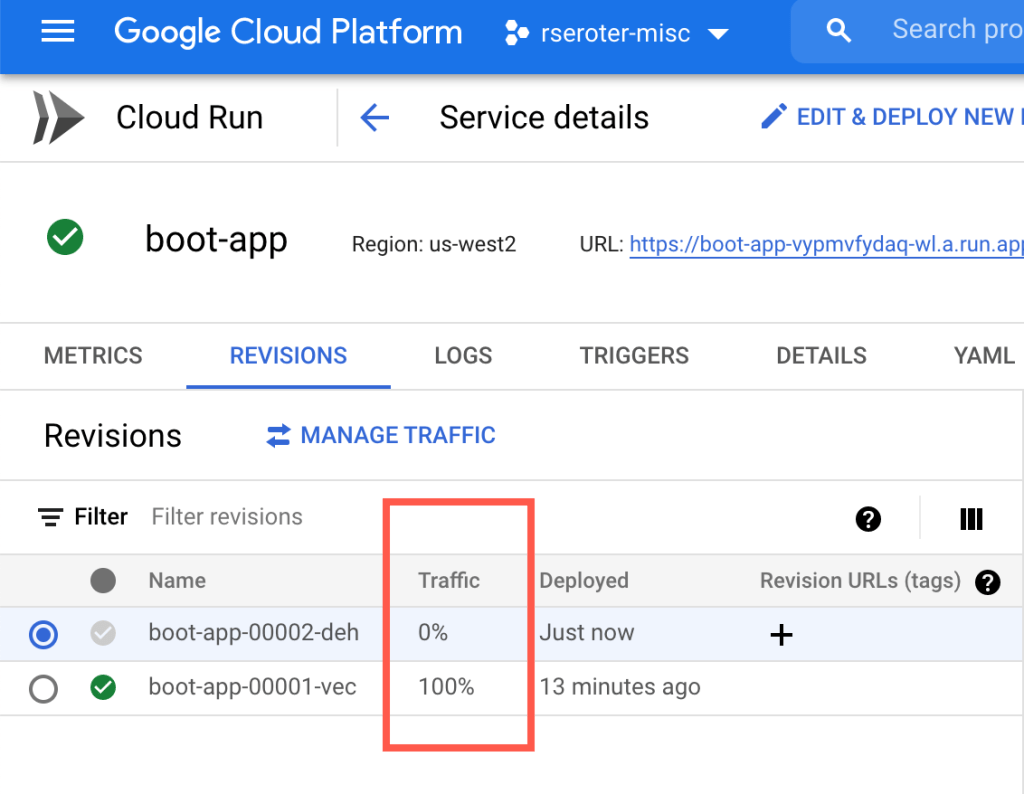

This time when I deployed, I chose the “no traffic” flag—cloud beta run deploy boot-app --memory=1024 --source . --no-traffic—so that I could control who saw the new field. Once it deployed, I saw two “revisions” and had the ability to choose the amount of traffic to send to each.

I switched 50% of the traffic to the new revision, liked what I saw, and then flipped it to 100%.

So there you go. It’s possible to fly through this inner loop in minutes. Because I’m leaning on managed serverless technologies for things like application runtime and database, I’m not wasting any time building or managing infrastructure. The local dev tooling from Google Cloud is terrific, so I have easy use of IDE integrations, emulators and build tools. This stack makes it simple for me to iterate quickly, cheaply, and with tech that feels like the future, versus wrestling with old stuff that’s been retrofitted for today’s needs.