Do you like using function-as-a-service (FaaS) platforms to quickly build scalable systems? Me too. There are constraints around what you can do with FaaS, which is why I also like this new crop of container-based serverless compute services. These products—the terrific Google Cloud Run is the most complete example and has a generous free tier—let you deploy more full-fledged “apps” versus the glue code that works best in FaaS. Could be a little Go app, full-blown Spring Boot REST API, or a Redis database. Sounds good, but what if you don’t want to mess with containers as you build and deploy software? Or are concerned about the “cold start” penalty of a denser workload?

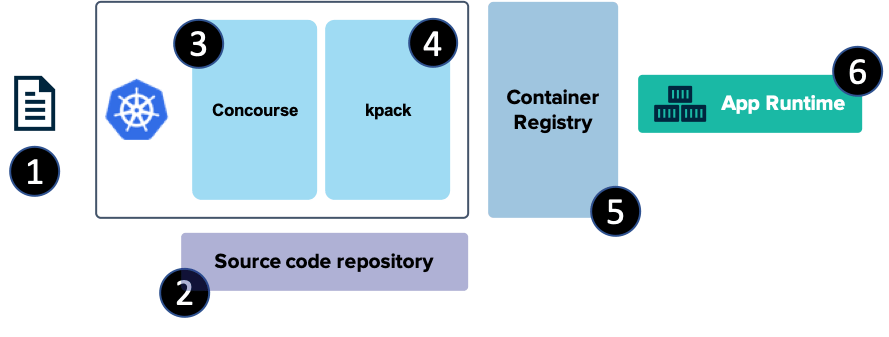

Google Cloud has embraced Cloud Buildpacks as a way to generate a container image from source code. Using our continuous integration service or any number of compute services directly, you never have to write a Dockerfile again, unless you want to. Hopefully, at least. Regarding the cold start topic, we just shipped a new cloud metric, “container startup latency” to measure the time it takes for a serverless instance to fire up. That seems like a helpful tool to figure out what needs to be optimized. Based on these two things, I got curious and decided to build the same REST API in four different programming languages to see how big the generated container image was, and how fast the containers started up in Cloud Run.

Since Cloud Run accepts most any container, you have almost limitless choices in programming language. For this example, I chose to use C#, Go, Java (Spring Boot), and JavaScript (Node.js). I built an identical REST API with each. It’s entirely possible, frankly likely, that you could tune these apps much more than I did. But this should give us a decent sense of how each language performs.

Let’s go language-by-language and review the app, generate the container image, deploy to Cloud Run, and measure the container startup latency.

Go

I’m almost exclusively coding in Go right now as I try to become more competent with it. Go has an elegant simplicity to it that I really enjoy. And it’s an ideal language for serverless environments given its small footprint, blazing speed, and easy concurrency.

For the REST API, which basically just returns a pair of “employee” records, I used the Echo web framework and Go 1.18.

My data model (struct) has four properties.

package model

type Employee struct {

Id string `json:"id"`

FullName string `json:"fullname"`

Location string `json:"location"`

JobTitle string `json:"jobtitle"`

}

My web handler offers a single operation that returns two employee items.

package web

import (

"net/http"

"github.com/labstack/echo/v4"

"seroter.com/restapi/model"

)

func GetAllEmployees(c echo.Context) error {

emps := [2]model.Employee{{Id: "100", FullName: "Jack Donaghy", Location: "NYC", JobTitle: "Executive"}, {Id: "101", FullName: "Liz Lemon", Location: "NYC", JobTitle: "Writer"}}

return c.JSON(http.StatusOK, emps)

}

And finally, the main Go class spins up the web server.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/labstack/echo/v4"

"github.com/labstack/echo/v4/middleware"

"seroter.com/restapi/web"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println("server started ...")

e := echo.New()

e.Use(middleware.Logger())

e.GET("/employees", web.GetAllEmployees)

e.Start(":8080")

}

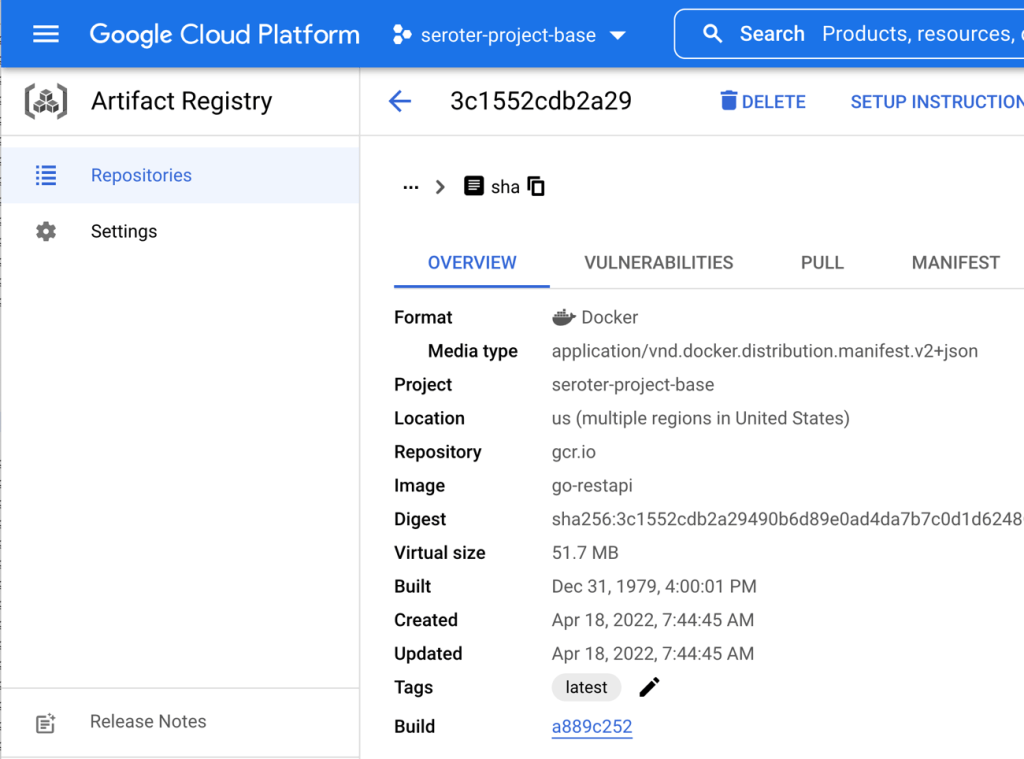

Next, I used Google Cloud Build along with Cloud Buildpacks to generate a container image from this Go app. The buildpack executes a build, brings in a known good base image, and creates an image that we add to Google Cloud Artifact Registry. It’s embarrassingly easy to do this. Here’s the single command with our gcloud CLI:

gcloud builds submit --pack image=gcr.io/seroter-project-base/go-restapi

The result? A 51.7 MB image in my Docker repository in Artifact Registry.

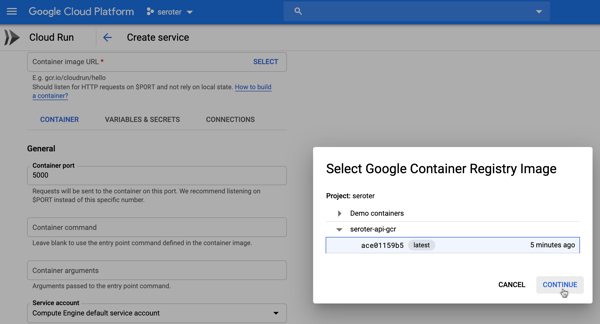

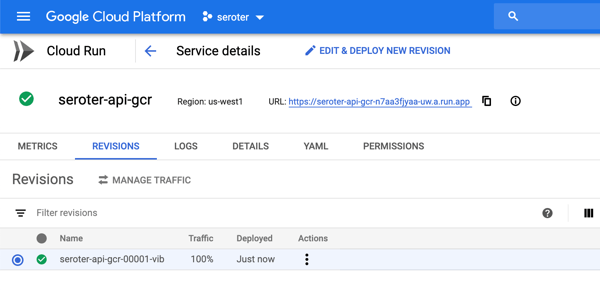

The last step was to deploy to Cloud Run. We could use the CLI of course, but let’s use the Console experience because it’s delightful.

After pointing at my generated container image, I could just click “create” and accept all the default instance properties. As you can see below, I’ve got easy control over instance count (minimum of zero, but you can keep a warm instance running if you want).

Let’s tweak a couple of things. First off, I don’t need the default amount of RAM. I can easily operate with just 256MiB, or even less. Also, you see here that we default to 80 concurrent requests per container. That’s pretty cool, as most FaaS platforms do a single concurrent request. I’ll stick with 80.

It seriously took four seconds from the time I clicked “create” until the instance was up and running and able to take traffic. Bonkers. I didn’t send any initial requests in, as I want to hit it cold with a burst of data. I’m using the excellent hey tool to generate a bunch of load on my service. This single command sends 200 total requests, with 10 concurrent workers.

hey -n 200 -c 10 https://go-restapi-ofanvtevaa-uc.a.run.app/employees

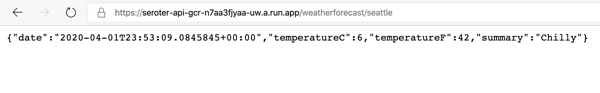

Here’s the result. All the requests were done in 2.6 seconds, and you can see that that the first ones (as the container warmed up) took 1.2 seconds, and the vast majority took 0.177 seconds. That’s fast.

Summary: Total: 2.6123 secs Slowest: 1.2203 secs Fastest: 0.0609 secs Average: 0.1078 secs Requests/sec: 76.5608 Total data: 30800 bytes Size/request: 154 bytes Response time histogram: 0.061 [1] | 0.177 [189] |■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ 0.293 [0] | 0.409 [0] | 0.525 [1] | 0.641 [6] |■ 0.757 [0] | 0.873 [0] | 0.988 [0] | 1.104 [0] | 1.220 [3] |■ Latency distribution: 10% in 0.0664 secs 25% in 0.0692 secs 50% in 0.0721 secs 75% in 0.0777 secs 90% in 0.0865 secs 95% in 0.5074 secs 99% in 1.2057 secs

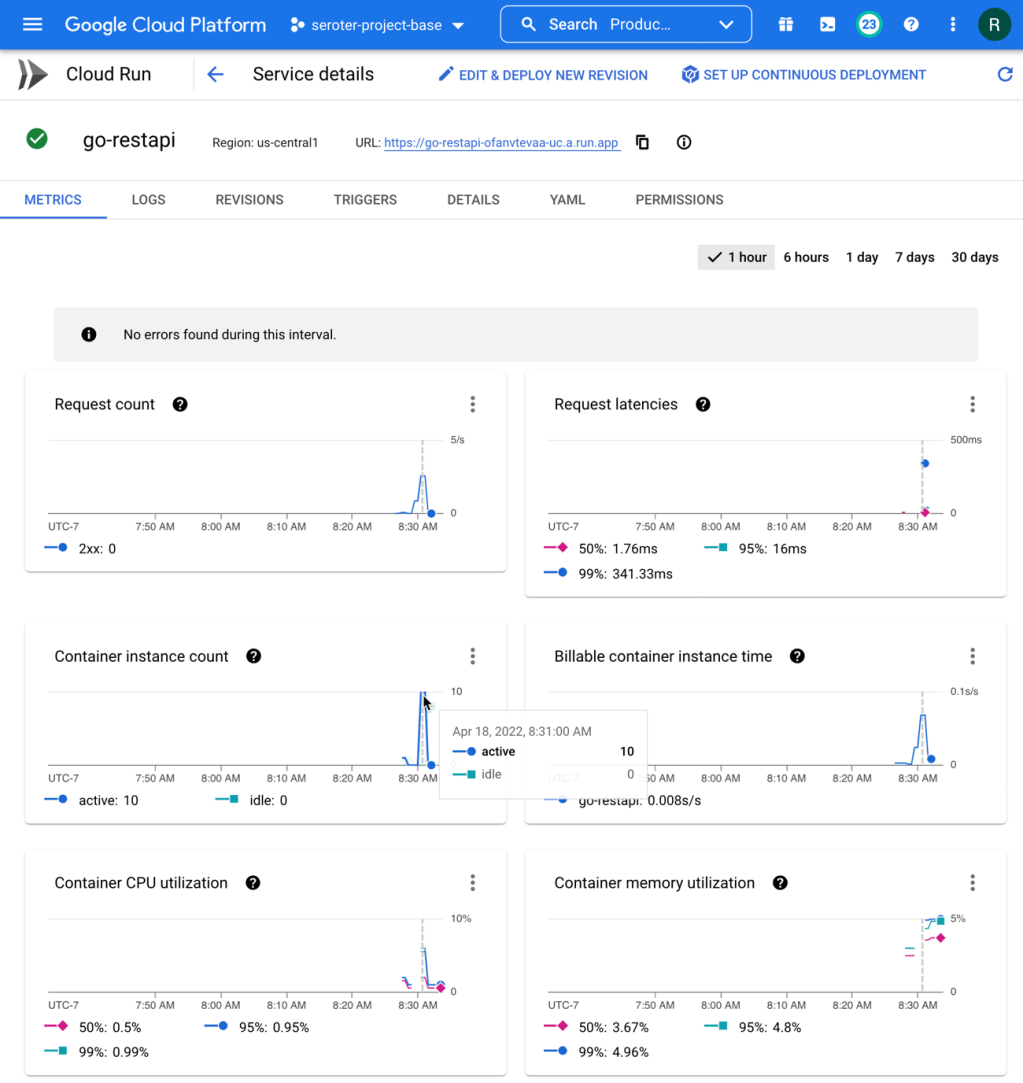

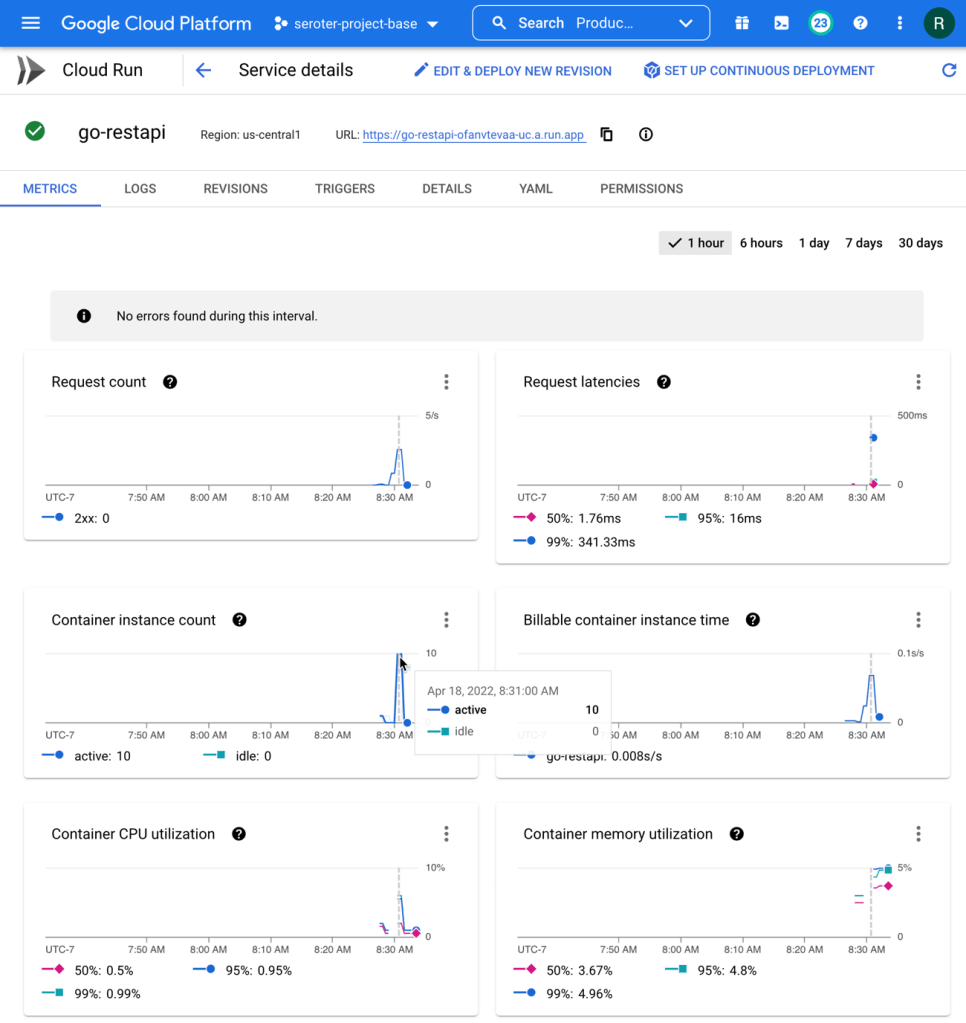

How about the service metrics? I saw that Cloud Run spun up 10 containers to handle the incoming load, and my containers topped out at 5% memory utilization. It also barely touched the CPU.

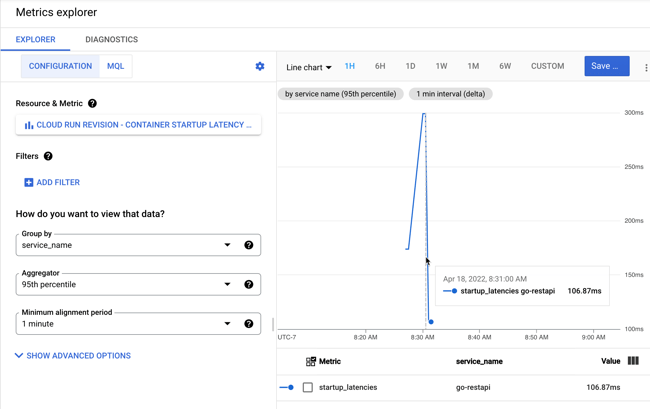

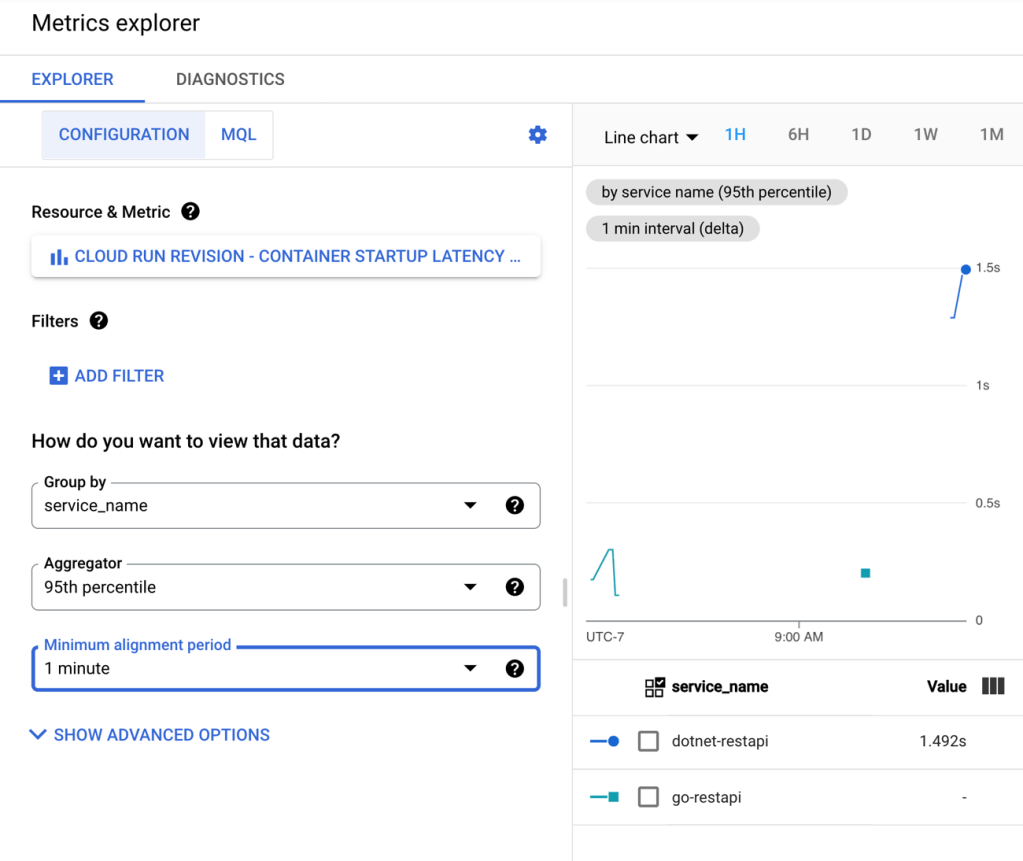

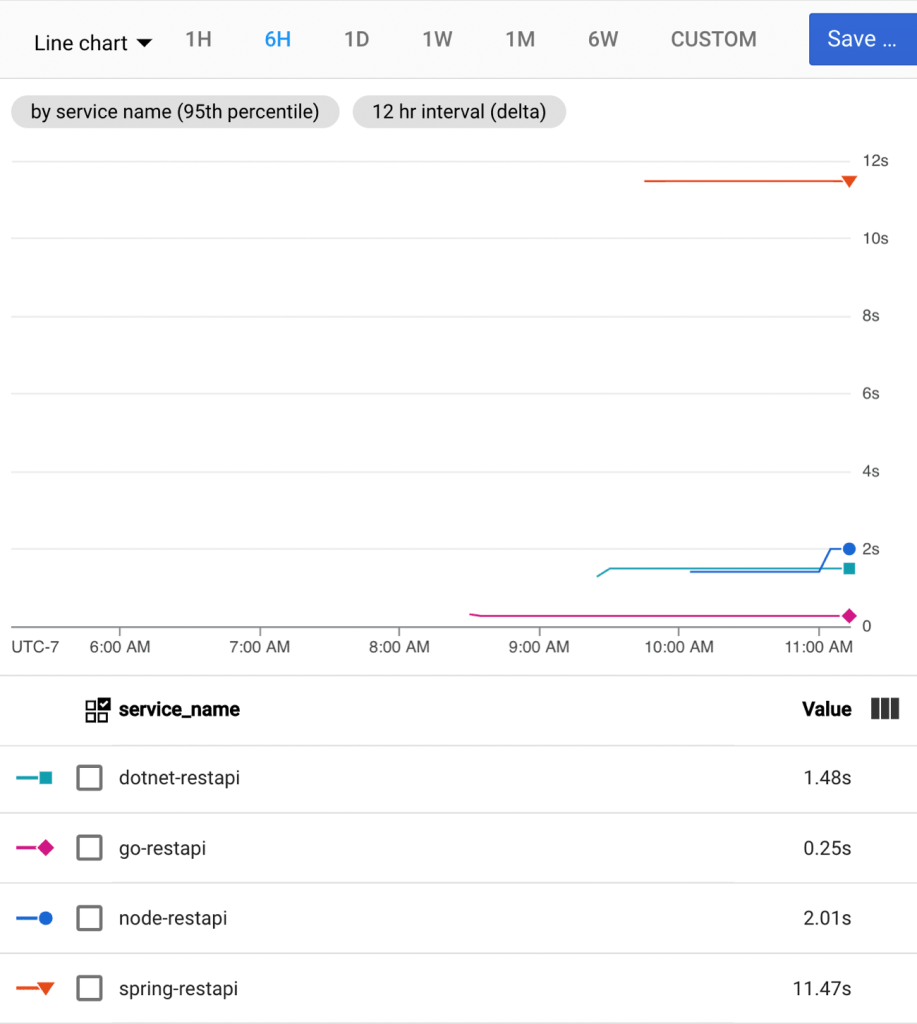

How about that new startup latency metric? I jumped into Cloud Monitoring directly to see that. There are lots of ways to aggregate this data (mean, standard deviation, percentile) and I chose the 95th percentile. My container startup time is pretty darn fast (at 95th percentile, it’s 106.87 ms), and then stays up to handle the load, so I don’t incur a startup cost for the chain of requests.

Finally, with some warm instances running, I ran the load test again. You can see how speedy things are, with virtually no “slow” responses. Go is an excellent choice for your FaaS or container-based workloads if speed matters.

Summary: Total: 2.1548 secs Slowest: 0.5008 secs Fastest: 0.0631 secs Average: 0.0900 secs Requests/sec: 92.8148 Total data: 30800 bytes Size/request: 154 bytes Response time histogram: 0.063 [1] | 0.107 [185] |■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ 0.151 [2] | 0.194 [10] |■■ 0.238 [0] | 0.282 [0] | 0.326 [0] | 0.369 [0] | 0.413 [0] | 0.457 [1] | 0.501 [1] | Latency distribution: 10% in 0.0717 secs 25% in 0.0758 secs 50% in 0.0814 secs 75% in 0.0889 secs 90% in 0.1024 secs 95% in 0.1593 secs 99% in 0.4374 secs

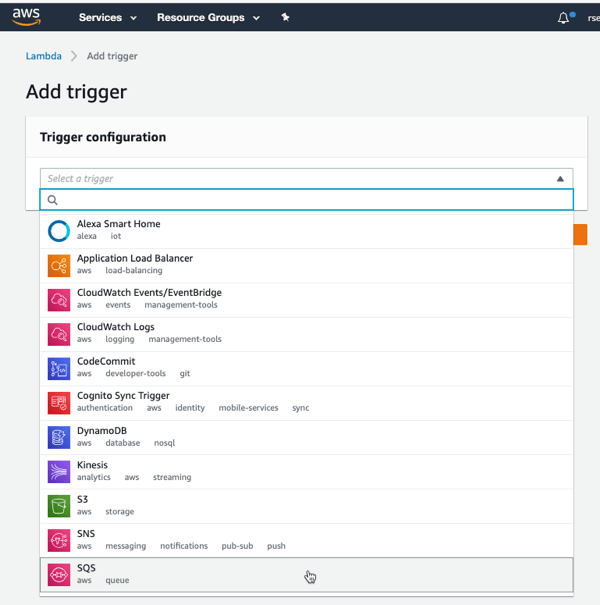

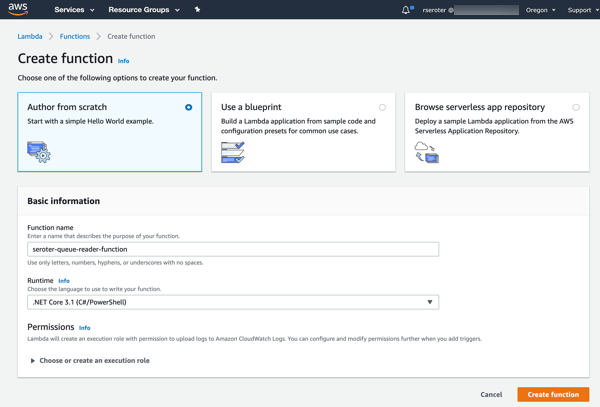

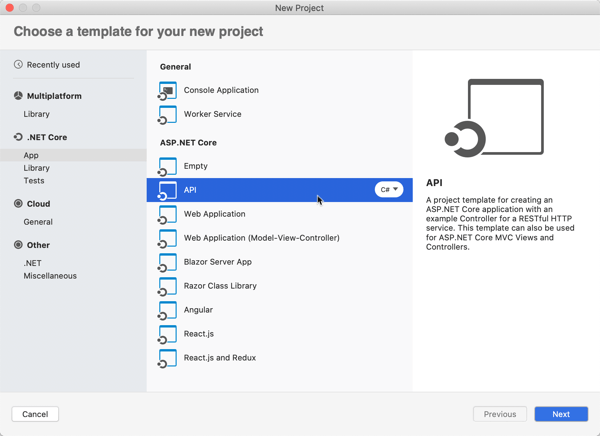

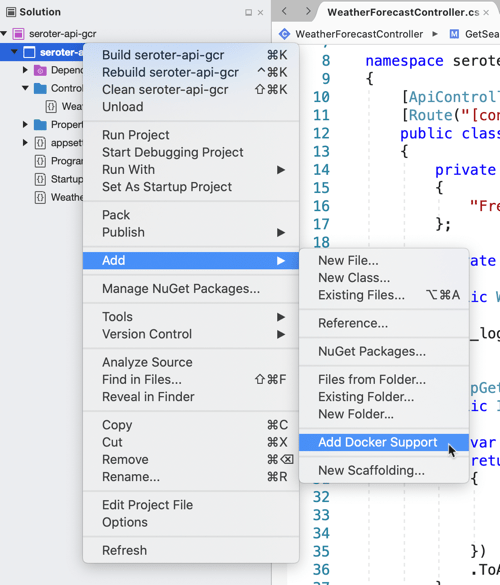

C# (.NET)

Ah, .NET. I started using it with the early preview release in 2000, and considered myself a (poor) .NET dev for most of my career. Now, I dabble. .NET 6 looks good, so I built my REST API with that.

Update: I got some good feedback from folks that I could have tried this .NET app using the new minimal API structure. I wasn’t sure it’d make a difference, but tried it anyway. Resulted in the same container size, and roughly the same response time (4.2088 seconds for all 200 requests) and startup latency (2.23s at 95th percentile). Close, but actually a tad slower! On the second pass of 200 requests, the total response time was almost equally (1.6915 seconds) fast as the way I originally wrote it.

My Employee object definition is straightforward.

namespace dotnet_restapi;

public class Employee {

public Employee(string id, string fullname, string location, string jobtitle) {

this.Id = id;

this.FullName = fullname;

this.Location = location;

this.JobTitle = jobtitle;

}

public string Id {get; set;}

public string FullName {get; set;}

public string Location {get; set;}

public string JobTitle {get; set;}

}

The Controller has a single operation and returns a List of employee objects.

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

namespace dotnet_restapi.Controllers;

[ApiController]

[Route("[controller]")]

public class EmployeesController : ControllerBase

{

private readonly ILogger<EmployeesController> _logger;

public EmployeesController(ILogger<EmployeesController> logger)

{

_logger = logger;

}

[HttpGet(Name = "GetEmployees")]

public IEnumerable<Employee> Get()

{

List<Employee> emps = new List<Employee>();

emps.Add(new Employee("100", "Bob Belcher", "SAN", "Head Chef"));

emps.Add(new Employee("101", "Philip Frond", "SAN", "Counselor"));

return emps;

}

}

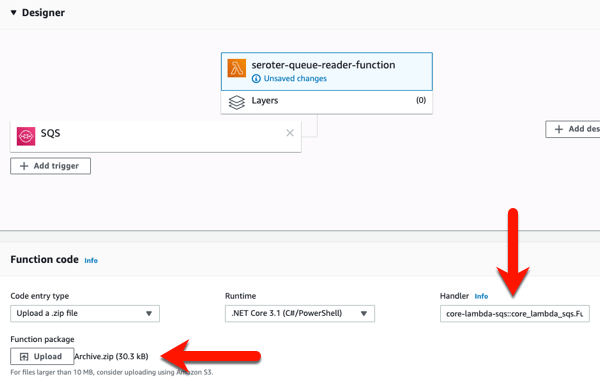

The program itself simply looks for an environment variable related to the HTTP port, and starts up the server. Much like above, to build this app and produce a container image, it only takes this one command:

gcloud builds submit --pack image=gcr.io/seroter-project-base/dotnet-restapi

The result is a fairly svelte 90.6 MB image in the Artifact Registry.

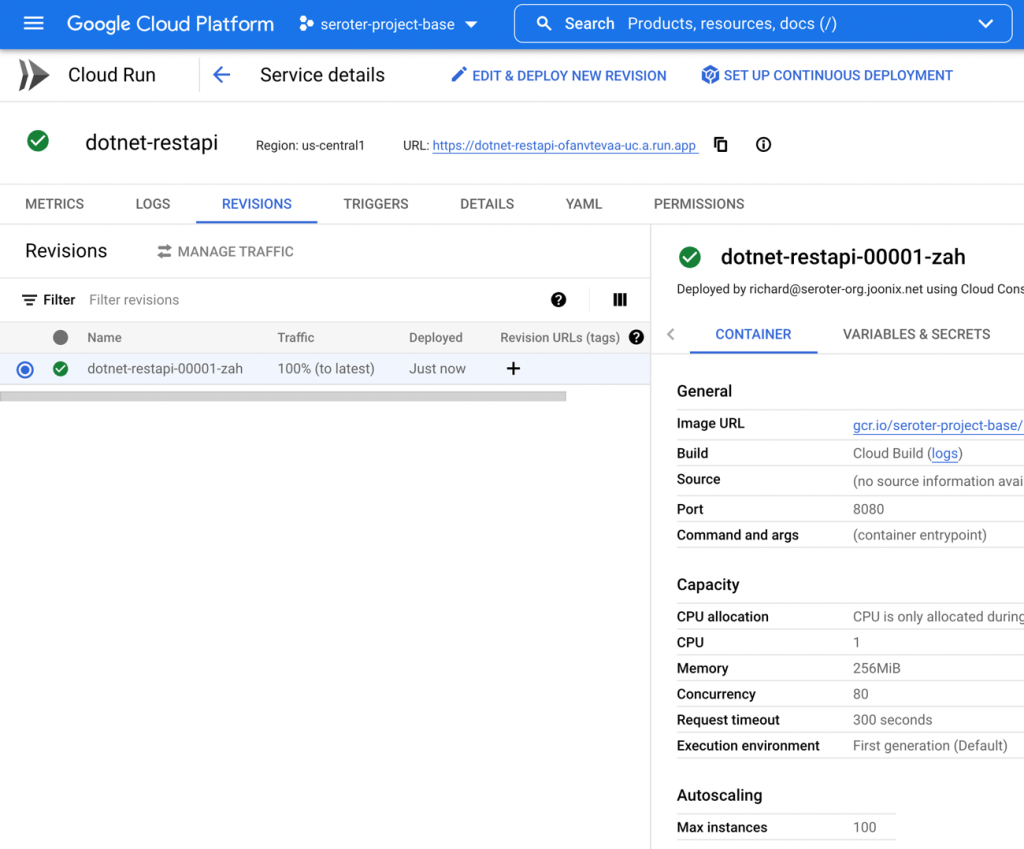

When deploying this instance to Cloud Run, I kept the same values as with the Go service, as my .NET app doesn’t need more than 256MiB of memory.

In just a few seconds, I had the app up and running.

Let’s load test this bad boy and see what happens. I sent in the same type of request as before, with 200 total requests, 10 concurrent.

hey -n 200 -c 10 https://dotnet-restapi-ofanvtevaa-uc.a.run.app/employees

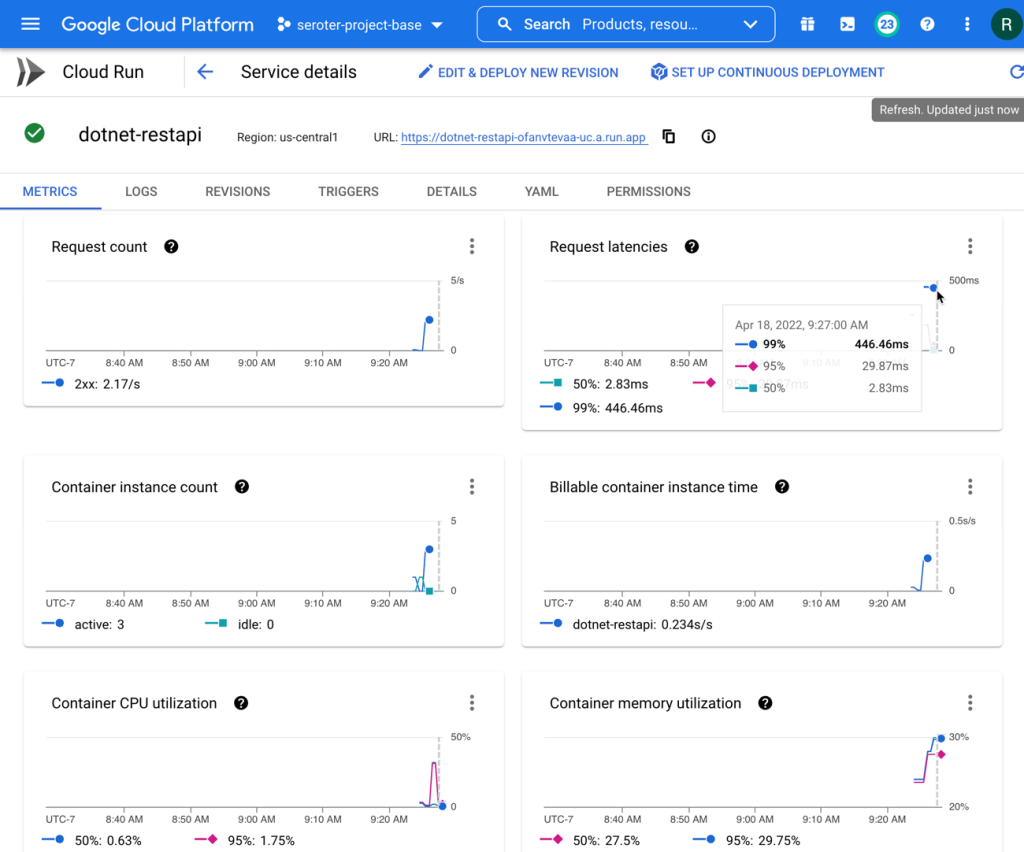

The results were solid. You can see a total execution time of about 3.6 seconds, with a few instances taking 2 seconds, and the rest coming back super fast.

Summary: Total: 3.6139 secs Slowest: 2.1923 secs Fastest: 0.0649 secs Average: 0.1757 secs Requests/sec: 55.3421 Response time histogram: 0.065 [1] | 0.278 [189] |■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ 0.490 [0] | 0.703 [0] | 0.916 [0] | 1.129 [0] | 1.341 [0] | 1.554 [0] | 1.767 [0] | 1.980 [0] | 2.192 [10] |■■ Latency distribution: 10% in 0.0695 secs 25% in 0.0718 secs 50% in 0.0747 secs 75% in 0.0800 secs 90% in 0.0846 secs 95% in 2.0365 secs 99% in 2.1286 secs

I checked the Cloud Run metrics, and see that request latency was high on a few requests, but the majority were fast. Memory was around 30% utilization. Very little CPU consumption.

For container startup latency, the number was 1.492s at the 95th percentile. Still not bad.

Oh, and sending in another 200 requests with my .NET containers warmed up resulted in some smokin’ fast responses.

Summary: Total: 1.6851 secs Slowest: 0.1661 secs Fastest: 0.0644 secs Average: 0.0817 secs Requests/sec: 118.6905 Response time histogram: 0.064 [1] | 0.075 [64] |■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ 0.085 [104] |■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ 0.095 [18] |■■■■■■■ 0.105 [2] |■ 0.115 [1] | 0.125 [0] | 0.136 [0] | 0.146 [0] | 0.156 [0] | 0.166 [10] |■■■■ Latency distribution: 10% in 0.0711 secs 25% in 0.0735 secs 50% in 0.0768 secs 75% in 0.0811 secs 90% in 0.0878 secs 95% in 0.1600 secs 99% in 0.1660 secs

Java (Spring Boot)

Now let’s try it with a Spring Boot application. I learned Spring when I joined Pivotal, and taught a couple Pluralsight courses on the topic. Spring Boot is a powerful framework, and you can build some terrific apps with it. For my REST API, I began at start.spring.io to generate my reactive web app.

The “employee” definition should look familiar at this point.

package com.seroter.springrestapi;

public class Employee {

private String Id;

private String FullName;

private String Location;

private String JobTitle;

public Employee(String id, String fullName, String location, String jobTitle) {

Id = id;

FullName = fullName;

Location = location;

JobTitle = jobTitle;

}

public String getId() {

return Id;

}

public String getJobTitle() {

return JobTitle;

}

public void setJobTitle(String jobTitle) {

this.JobTitle = jobTitle;

}

public String getLocation() {

return Location;

}

public void setLocation(String location) {

this.Location = location;

}

public String getFullName() {

return FullName;

}

public void setFullName(String fullName) {

this.FullName = fullName;

}

public void setId(String id) {

this.Id = id;

}

}

Then, my Controller + main class exposes a single REST endpoint and returns a Flux of employees.

package com.seroter.springrestapi;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

import org.springframework.boot.SpringApplication;

import org.springframework.boot.autoconfigure.SpringBootApplication;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.GetMapping;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RestController;

import reactor.core.publisher.Flux;

@RestController

@SpringBootApplication

public class SpringRestapiApplication {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(SpringRestapiApplication.class, args);

}

List<Employee> employees;

public SpringRestapiApplication() {

employees = new ArrayList<Employee>();

employees.add(new Employee("300", "Walt Longmire", "WYG", "Sheriff"));

employees.add(new Employee("301", "Vic Moretti", "WYG", "Deputy"));

}

@GetMapping("/employees")

public Flux<Employee> getAllEmployees() {

return Flux.fromIterable(employees);

}

}

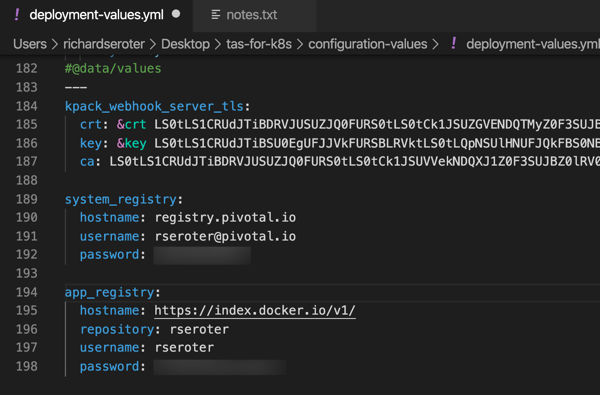

I could have done some more advanced configuration to create a slimmer JAR file, but I wanted to try this with the default experience. Once again, I used a single Cloud Build command to generate a container from this app. I do appreciate how convenient this is!

gcloud builds submit --pack image=gcr.io/seroter-project-base/spring-restapi

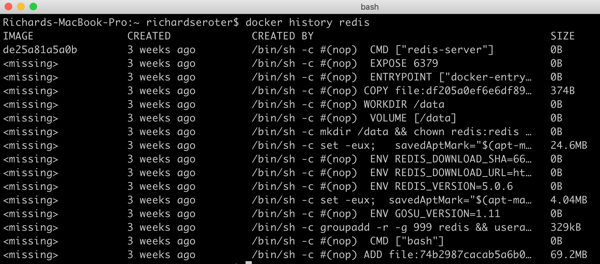

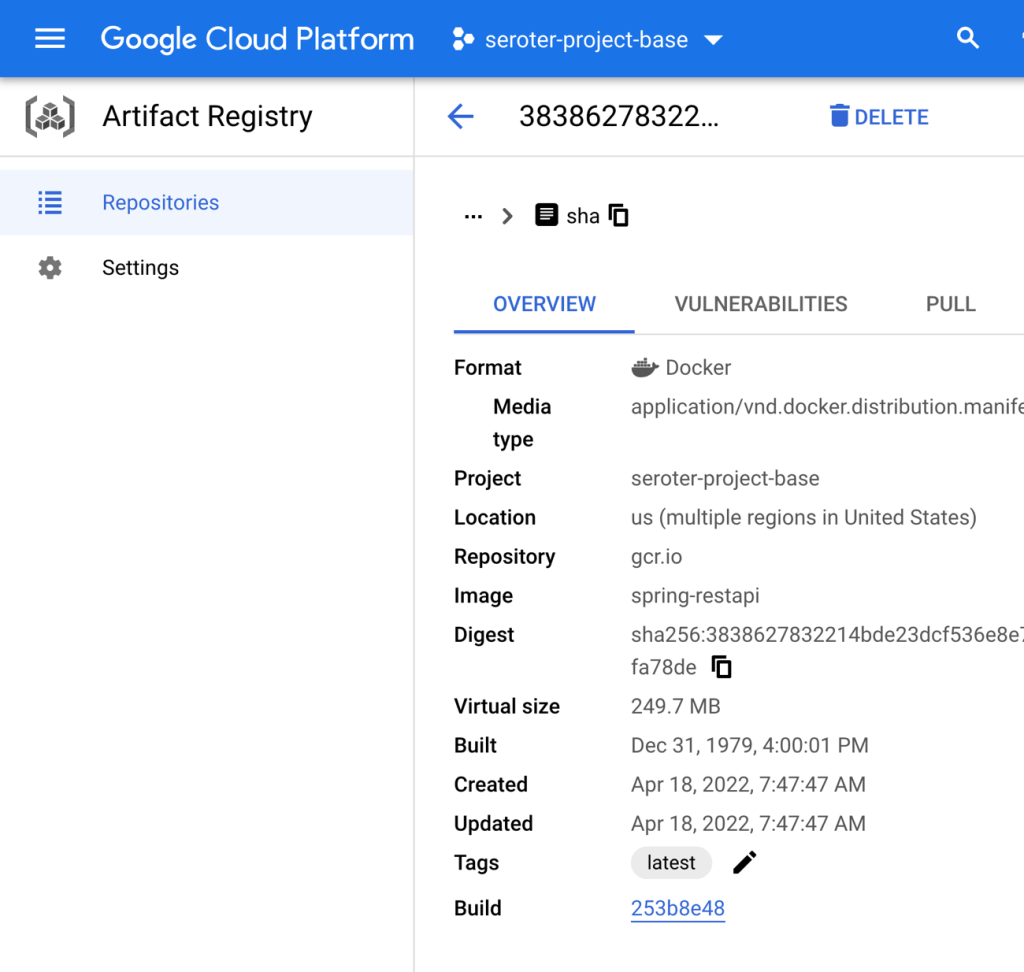

Not surpassingly, a Java container image is a bit hefty. This one clocks in at 249.7 MB in size. The container image size doesn’t matter a TON to Cloud Run, as we do image streaming from Artifact Registry which means only files loaded by your app need to be pulled. But, size still does matter a bit here.

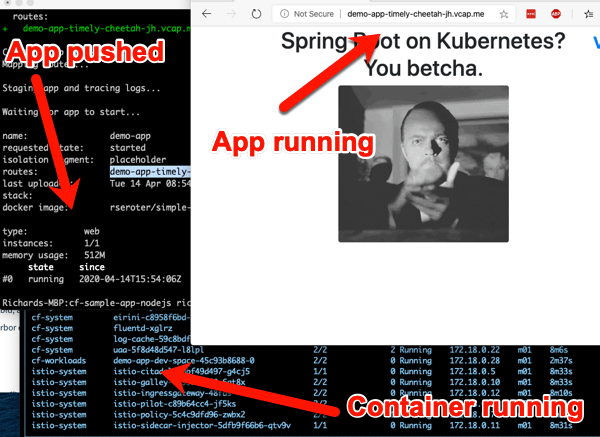

When deploying this image to Cloud Run, I did keep the default 512 MiB of memory in place as a Java app can tend to consume more resources. The service still deployed in less than 10 seconds, which is awesome. Let’s flood it with traffic.

hey -n 200 -c 10 https://spring-restapi-ofanvtevaa-uc.a.run.app/employees

200 requests to my Spring Boot endpoint did ok. Clearly there’s a big startup time on the first one(s), and as a developer, that’d be where I dedicate extra time to optimizing.

Summary: Total: 13.8860 secs Slowest: 12.3335 secs Fastest: 0.0640 secs Average: 0.6776 secs Requests/sec: 14.4030 Response time histogram: 0.064 [1] | 1.291 [189] |■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ 2.518 [0] | 3.745 [0] | 4.972 [0] | 6.199 [0] | 7.426 [0] | 8.653 [0] | 9.880 [0] | 11.107 [0] | 12.333 [10] |■■ Latency distribution: 10% in 0.0723 secs 25% in 0.0748 secs 50% in 0.0785 secs 75% in 0.0816 secs 90% in 0.0914 secs 95% in 11.4977 secs 99% in 12.3182 secs

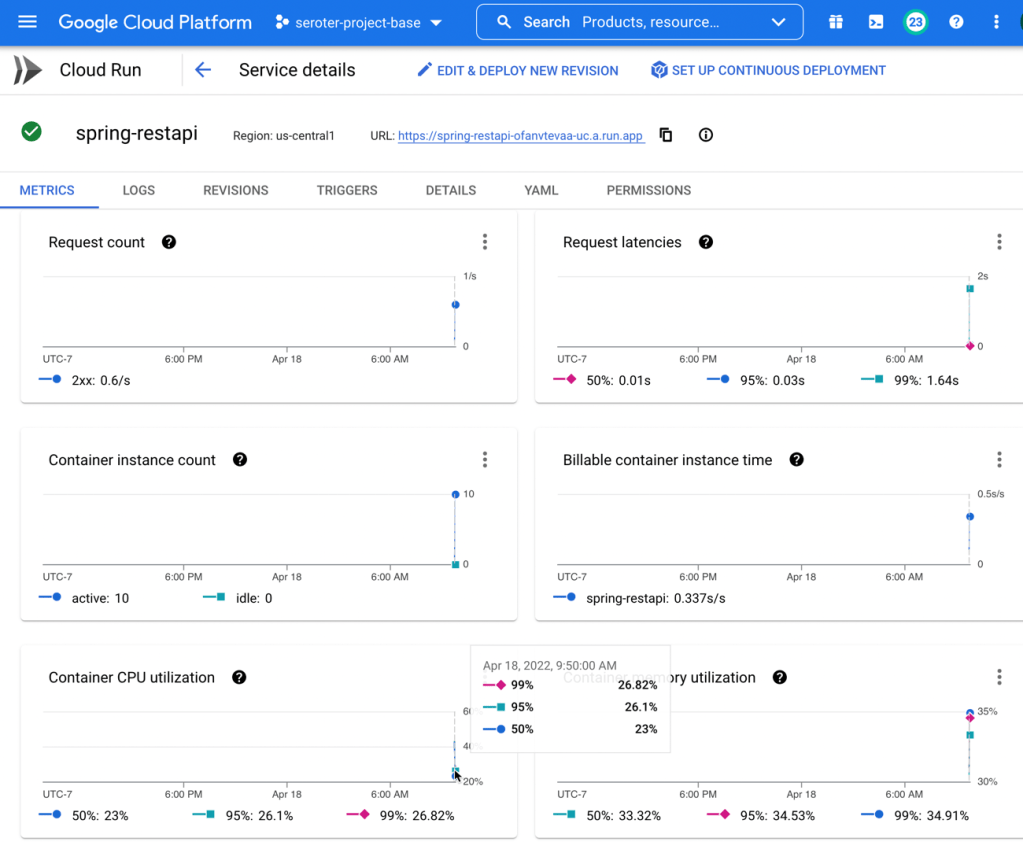

The initial Cloud Run metrics show fast request latency (routing to the service), 10 containers to handle the load, and a somewhat-high CPU and memory load.

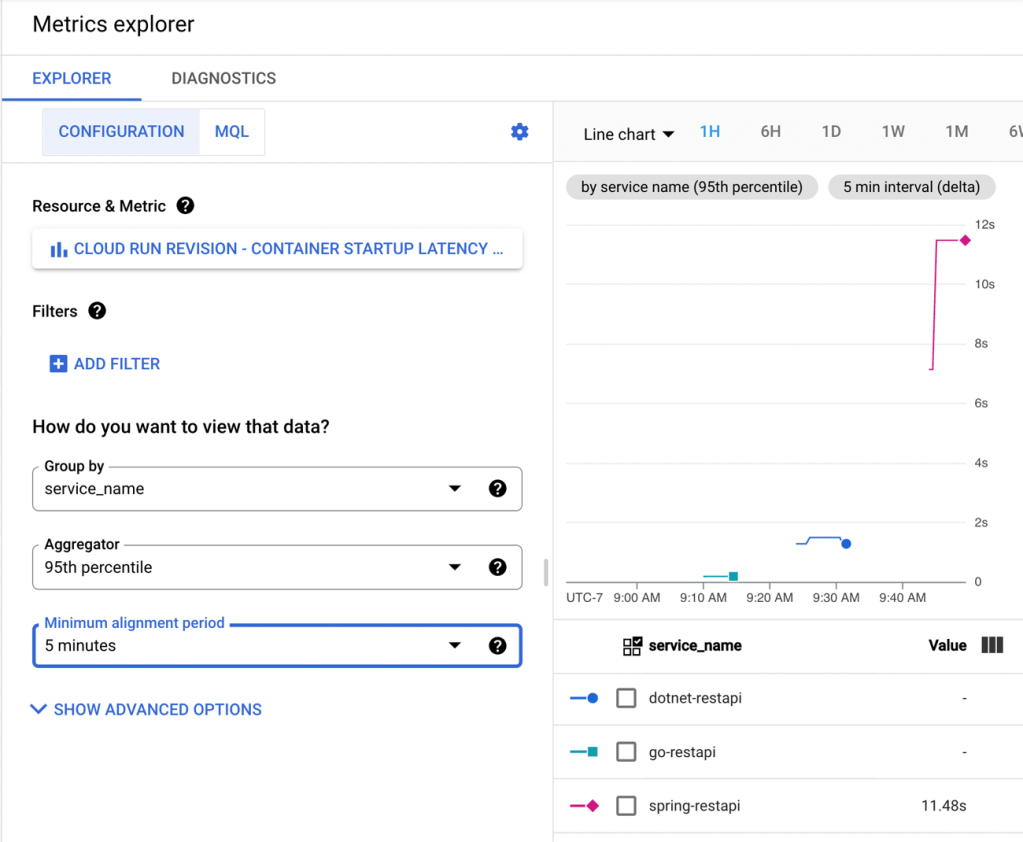

Back in Cloud Monitoring, I saw that the 95th percentile for container startup latency was 11.48s.

If you’re doing Spring Boot with serverless runtimes, you’re going to want to pay special attention to the app startup latency, as that’s where you’ll get the most bang for the buck. And consider doing a “minimum” of at least 1 always-running instance. See that when I sent in another 200 requests with warm containers running, things look good.

Summary: Total: 1.8128 secs Slowest: 0.2451 secs Fastest: 0.0691 secs Average: 0.0890 secs Requests/sec: 110.3246 Response time histogram: 0.069 [1] | 0.087 [159] |■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ 0.104 [27] |■■■■■■■ 0.122 [3] |■ 0.140 [0] | 0.157 [0] | 0.175 [0] | 0.192 [0] | 0.210 [0] | 0.227 [0] | 0.245 [10] |■■■ Latency distribution: 10% in 0.0745 secs 25% in 0.0767 secs 50% in 0.0802 secs 75% in 0.0852 secs 90% in 0.0894 secs 95% in 0.2365 secs 99% in 0.2450 secs

JavaScript (Node.js)

Finally, let’s look at JavaScript. This is what I first learned to really program in back in 1998-ish and then in my first job out of college. It continues to be everywhere, and widely supported in public clouds. For this Node.js REST API, I chose to use the Express framework. I built a simple router that returns a couple of “employee” records as JSON.

var express = require('express');

var router = express.Router();

/* GET employees */

router.get('/', function(req, res, next) {

res.json(

[{

id: "400",

fullname: "Beverly Goldberg",

location: "JKN",

jobtitle: "Mom"

},

{

id: "401",

fullname: "Dave Kim",

location: "JKN",

jobtitle: "Student"

}]

);

});

module.exports = router;

My app.js file calls out the routes and hooks it up to the /employees endpoint.

var express = require('express');

var path = require('path');

var cookieParser = require('cookie-parser');

var logger = require('morgan');

var indexRouter = require('./routes/index');

var employeesRouter = require('./routes/employees');

var app = express();

app.use(logger('dev'));

app.use(express.json());

app.use(express.urlencoded({ extended: false }));

app.use(cookieParser());

app.use(express.static(path.join(__dirname, 'public')));

app.use('/', indexRouter);

app.use('/employees', employeesRouter);

module.exports = app;

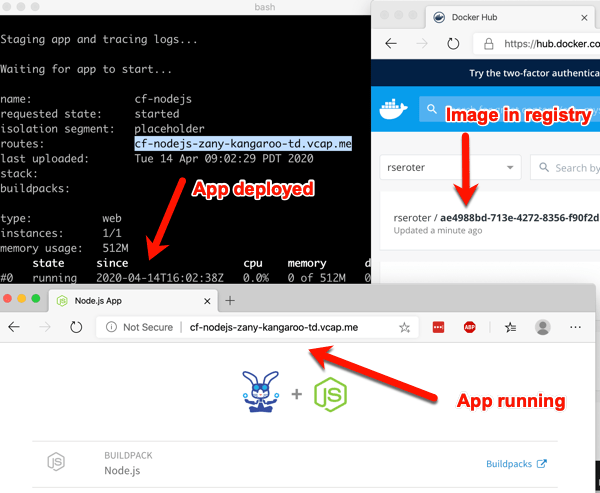

At this point, you know what it looks like to build a container image. But, don’t take it for granted. Enjoy how easy it is to do this even if you know nothing about Docker.

gcloud builds submit --pack image=gcr.io/seroter-project-base/node-restapi

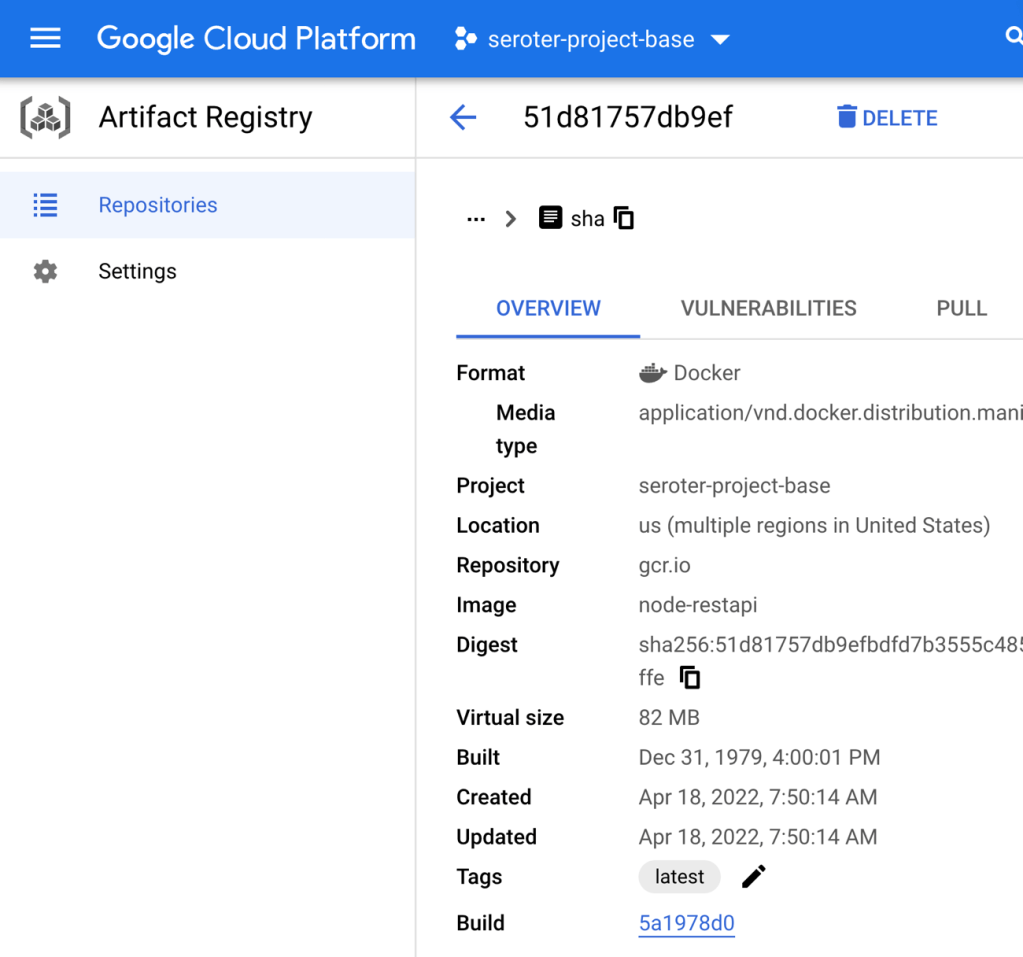

Our resulting image is a trim 82 MB in size. Nice!

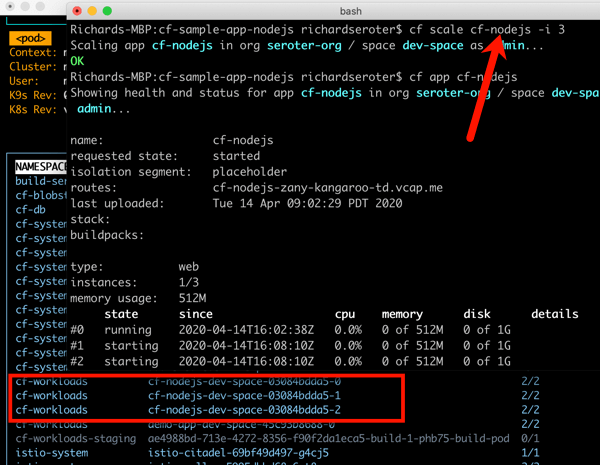

For my Node.js app, I chose the default options for Cloud Run, but shrunk the memory demands to only 256 MiB. Should be plenty. The service deployed in a few seconds. Let’s flood it with requests!

hey -n 200 -c 10 https://node-restapi-ofanvtevaa-uc.a.run.app/employees

How did our cold Node.js app do? Well! All requests were processed in about 6 seconds, and the vast majority returned a response in around 0.3 seconds.

Summary: Total: 6.0293 secs Slowest: 2.8199 secs Fastest: 0.0650 secs Average: 0.2309 secs Requests/sec: 33.1711 Total data: 30200 bytes Size/request: 151 bytes Response time histogram: 0.065 [1] | 0.340 [186] |■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ 0.616 [0] | 0.891 [0] | 1.167 [0] | 1.442 [1] | 1.718 [1] | 1.993 [1] | 2.269 [0] | 2.544 [4] |■ 2.820 [6] |■ Latency distribution: 10% in 0.0737 secs 25% in 0.0765 secs 50% in 0.0805 secs 75% in 0.0855 secs 90% in 0.0974 secs 95% in 2.4700 secs 99% in 2.8070 secs

A peek at the default Cloud Run metrics show that we ended up with 10 containers handling traffic, some CPU and memory spikes, a low request latency.

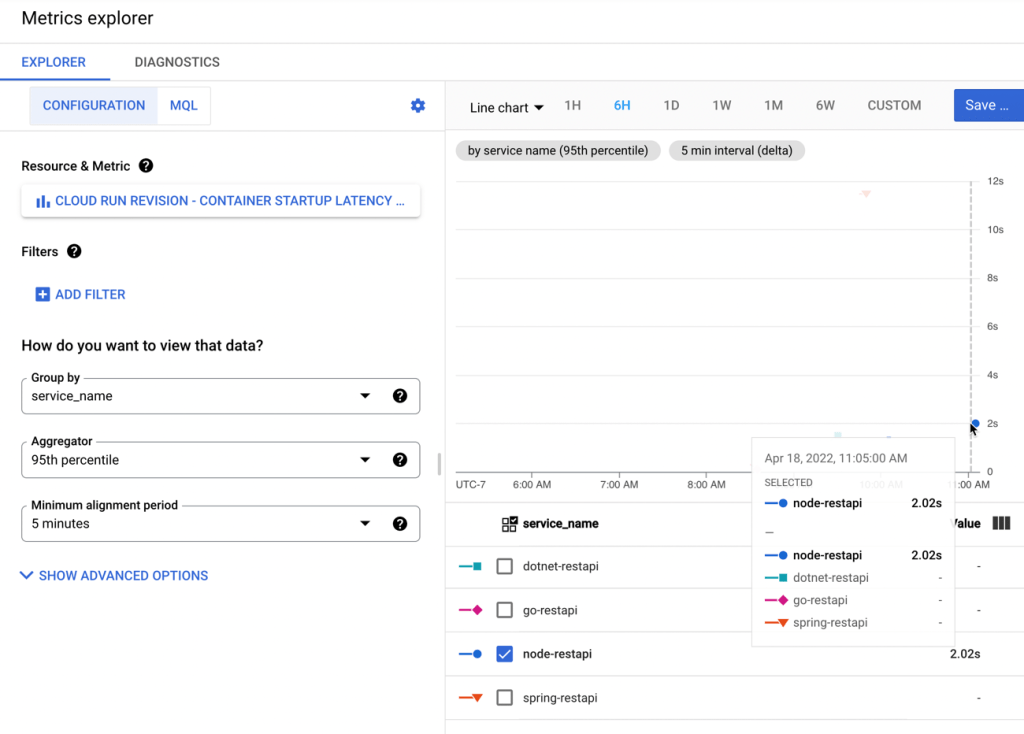

The specific metrics around container startup latency shows a very quick initial startup time of 2.02s.

A final load against our Node.js app shows some screaming performance against the warm containers.

Summary: Total: 1.8458 secs Slowest: 0.1794 secs Fastest: 0.0669 secs Average: 0.0901 secs Requests/sec: 108.3553 Total data: 30200 bytes Size/request: 151 bytes Response time histogram: 0.067 [1] | 0.078 [29] |■■■■■■■■■■ 0.089 [114] |■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ 0.101 [34] |■■■■■■■■■■■■ 0.112 [6] |■■ 0.123 [6] |■■ 0.134 [0] | 0.146 [0] | 0.157 [0] | 0.168 [7] |■■ 0.179 [3] |■ Latency distribution: 10% in 0.0761 secs 25% in 0.0807 secs 50% in 0.0860 secs 75% in 0.0906 secs 90% in 0.1024 secs 95% in 0.1608 secs 99% in 0.1765 secs

Wrap up

I’m not a performance engineer by any stretch, but doing this sort of testing with out-of-the-box settings seemed educational. My final container startup latency numbers at the 95th percentile were:

There are many ways to change these numbers. If you have a more complex app with more dependencies, it’ll likely be a bigger container image and possibly a slower startup. If you tune the app to do lazy loading or ruthlessly strip out unnecessary activation steps, your startup latency goes down. It still feels safe to say that if performance is a top concern, look at Go. C# and JavaScript apps are going to be terrific here as well. Be more cautious with Java if you’re truly scaling to zero, as you may not love the startup times.

The point of this exercise was to explore how apps written in each language get packaged and started up in a serverless compute environment. Something I missed or got wrong? Let me know in the comments!