It’s been nine years since I first tried out Cloud Foundry, and it remains my favorite app platform. It runs all kinds of apps, has a nice dev UX for deploying and managing software, and doesn’t force me to muck with infrastructure. The VMware team keeps shipping releases (another today) of the most popular packaging of Cloud Foundry, Tanzu Application Service (TAS). One knock against Cloud Foundry has been its weight—in typically runs on dozens of VMs. Others have commented on its use of open-source, but not widely-used, components like BOSH, the Diego scheduler, and more. I think there are good justifications for its size and choice of plumbing components, but I’m not here to debate that. Rather, I want to look at what’s next. The new Tanzu Application Service (TAS) for Kubernetes (now in beta) eliminates those prior concerns with Cloud Foundry, and just maybe, leapfrogs other platforms by delivering the dev UX you like, with the underlying components—things like Kubernetes, Cluster API, Istio, Envoy, fluentd, and kpack—you want. Let me show you.

TAS runs on any Kubernetes cluster: on-premises or in the cloud, VM-based or a managed service, VMware-provided or delivered by others. It’s based on the OSS Cloud Foundry for Kubernetes project, and available for beta download with a free (no strings attached) Tanzu Network account. You can follow along with me in this post, and in just a few minutes, have a fully working app platform that accepts containers or source code and wires it all up for you.

Step 1 – Download and Start Stuff (5 minutes)

Let’s get started. Some of these initial steps will go away post-beta as the install process gets polished up. But we’re brave explorers, and like trying things in their gritty, early stages, right?

First, we need a Kubernetes. That’s the first big change for Cloud Foundry and TAS. Instead of pointing it at any empty IaaS and using BOSH to create VMs, Cloud Foundry now supports bring-your-own-Kubernetes. I’m going to use Minikube for this example. You can use KinD, or any other number of options.

Install kubectl (to interact with the Kubernetes cluster), and then install Minikube. Ensure you have a recent version of Minikube, as we’re using the Docker driver for better performance. With Minikube installed, execute the following command to build out our single-node cluster. TAS for Kubernetes is happiest running on a generously-sized cluster.

minikube start --cpus=4 --memory=8g --kubernetes-version=1.15.7 --driver=docker

After a minute or two, you’ll have a hungry Kubernetes cluster running, just waiting for workloads.

We also need a few command line tools to get TAS installed. These tools, all open source, do things like YAML templating, image building, and deploying things like Cloud Foundry as an “app” to Kubernetes. Install the lightweight kapp, klbd, and ytt tools using these simple instructions.

You also need the Cloud Foundry command line tool. This is for interacting with the environment, deploying apps, etc. This same CLI works against a VM-based Cloud Foundry, or Kubernetes-based one. You can download the latest version via your favorite package manager or directly.

Finally, you’ll want to install the BOSH CLI. Wait a second, you say, didn’t you say BOSH wasn’t part of this? Am I just a filthy liar? First off, no name calling, you bastards. Secondly, no, you don’t need to use BOSH, but the CLI itself helps generate some configuration values we’ll use in a moment. You can download the BOSH CLI via your favorite package manager, or grab it from the Tanzu Network. Install via the instructions here.

With that, we’re done the environmental setup.

Step 2 – Generate Stuff (2 minute)

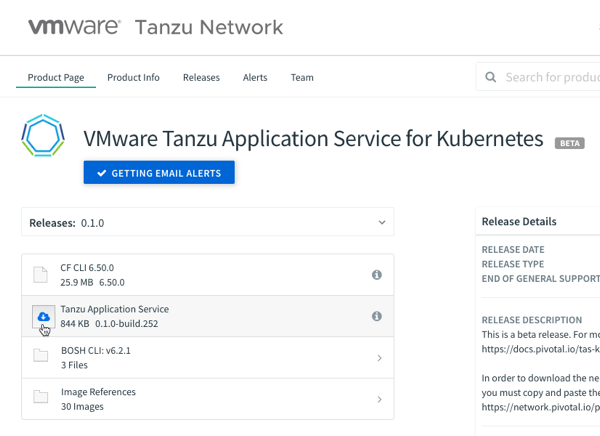

This is quick and easy. Download the 844KB TAS for Kubernetes bundle from the Tanzu Network.

I downloaded the archive to my desktop, unpacked it, and renamed the folder “tanzu-application-service.” Create a sibling folder named “configuration-values.”

Now we’re going to create the configuration file. Run the following command in your console, which should be pointed at the tanzu-application-service directory. The first quoted value is the domain. For my local instance, this value is vcap.me. When running this in a “real” environment, this value is the DNS name associated with your cluster and ingress point. The output of this command is a new file in the configuration-values folder.

./bin/generate-values.sh -d "vcap.me" > ../configuration-values/deployment-values.yml

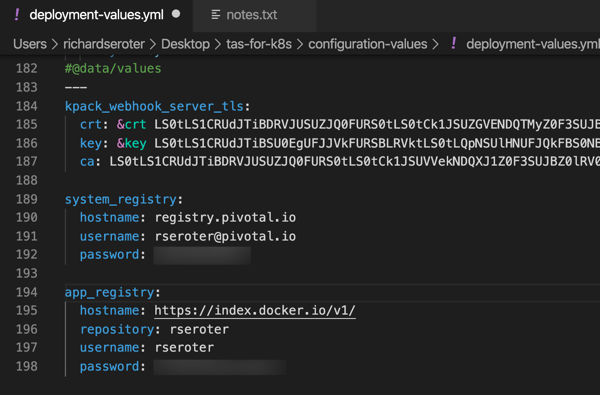

After a couple of seconds, we have an impressive-looking YAML file with passwords, certificates, and all sorts of delightful things.

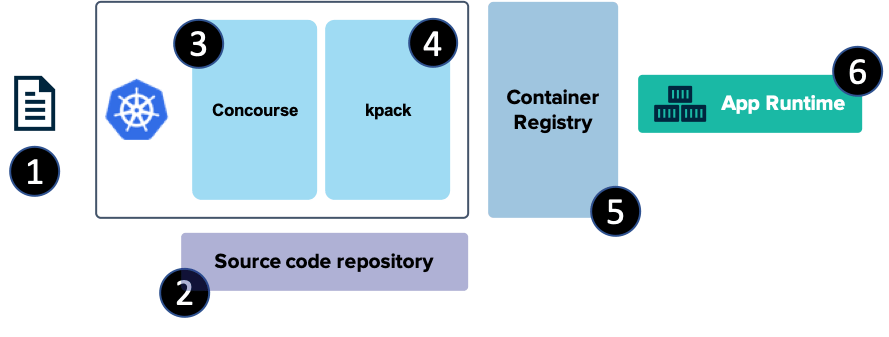

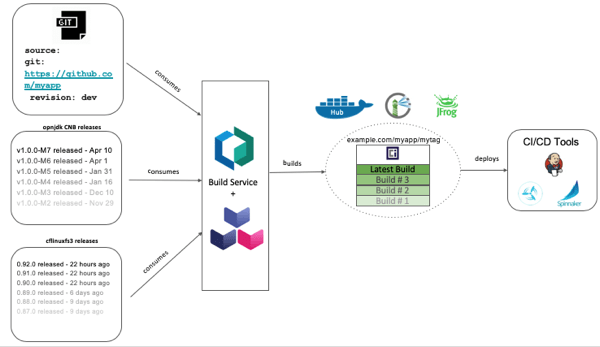

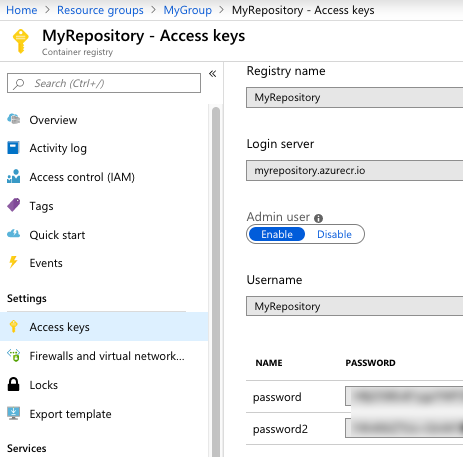

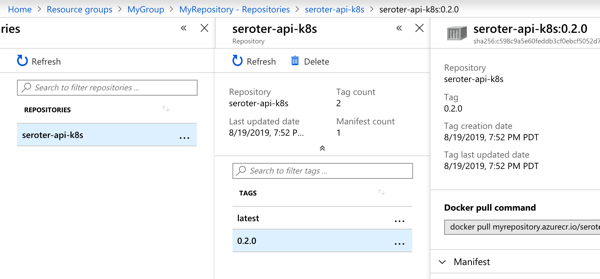

We’re nearly done. Our TAS environment won’t just run containers; it will also use kpack and Cloud Native Buildpacks to generate secure container images from source code. That means we need a registry for stashing generated images. You can use most any one you want. I’m going to use Docker Hub. Thus, the final configuration values we need are appended to the above file. First, we need the credentials to the Tanzu Network for retrieving platform images, and secondly, credentials for container registry.

With our credentials in hand, add them to the very bottom of the file. Indentation matters, this is YAML after all, so ensure you’ve got it lined up right.

The last thing? There’s a file that instructs the installation to create a cluster IP ingress point versus a Kubernetes load balancer resource. For Minikube (and in public cloud Kubernetes-as-a-Service environments) I want the load balancer. So, within the tanzu-application-service folder, move the replace-loadbalancer-with-clusterip.yaml file from the custom-overlays folder to the config-optional folder.

Finally, to be safe, I created a copy of this remove-resource-requirements.yml file and put it in the custom-overlays folder. It relaxes some of the resource expectations for the cluster. You may not need it, but I saw CPU exhaustion issues pop up when I didn’t use it.

All finished. Let’s deploy this rascal.

Step 3 – Deploy Stuff (10 minutes)

Deploying TAS to Kubernetes takes 5-9 minutes. With your console pointed at the tanzu-application-service directory, run this command:

./bin/install-tas.sh ../configuration-values

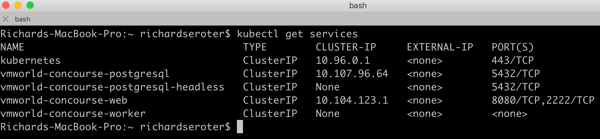

There’s a live read-out of progress, and you can also keep checking the Kubernetes environment to see the pods inflate. Tools like k9s make it easy to keep an eye on what’s happening. Notice the Istio components, and some familiar Cloud Foundry pieces. Observe that the entire Cloud Foundry control plane is containerized here—no VMs anywhere to be seen.

While this is still installing, let’s open up the Minikube tunnel to expose the LoadBalancer service our ingress gateway needs. Do this in a separate console window, as its a blocking call. Note that the installation can’t complete until you do it!

minikube tunnel

After a few minutes, we’re ready to deploy workloads.

Step 4 – Test Stuff (3 minutes)

We now have a full-featured Tanzu Application Service up and running. Neat. Let’s try a few things. First, we need to point the Cloud Foundry CLI at our environment.

cf api --skip-ssl-validation https://api.vcap.me

Great. Next, we log in, using generated cf_admin_password from the deployment-values.yaml file.

cf auth admin <password>

After that, we’ll enable containers in the environment.

cf enable-feature-flag diego_docker

Finally, we set up a tenant. Cloud Foundry natively supports isolation between tenants. Here, I set up an organization, and within that organization, a “space.” Finally, I tell the Cloud Foundry CLI that we’re working with apps in that particular org and space.

cf create-org seroter-org cf create-space -o seroter-org dev-space cf target -o seroter-org -s dev-space

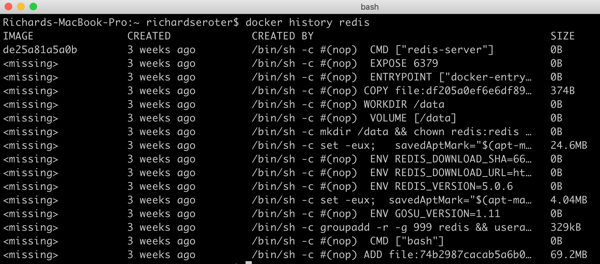

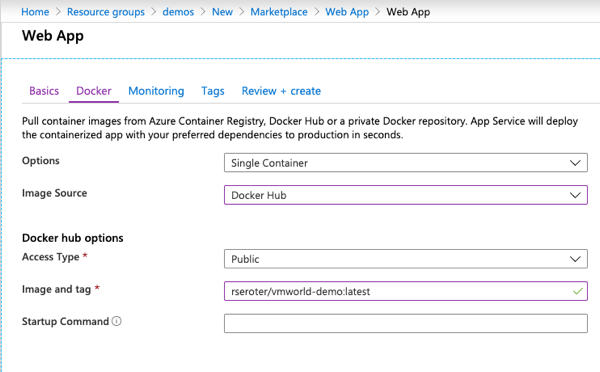

Let’s do something easy, first. Push a previously-containerized app. Here’s one from my Docker Hub, but it can be anything you want.

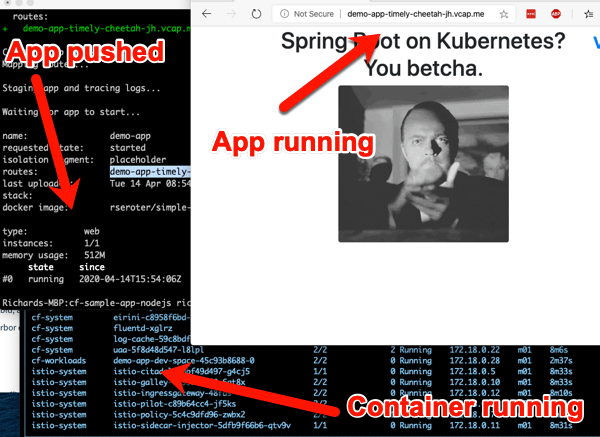

cf push demo-app -o rseroter/simple-k8s-app-kpack

After you enter that command, 15 seconds later you have a hosted, routable app. The URL is presented in the Cloud Foundry CLI.

How about something more interesting? TAS for Kubernetes supports a variety of buildpacks. These buildpacks detect the language of your app, and then assemble a container image for you. Right now, the platform builds Java, .NET Core, Go, and Node.js apps. To make life simple, clone this sample Node app to your machine. Navigate your console to that folder, and simple enter cf push.

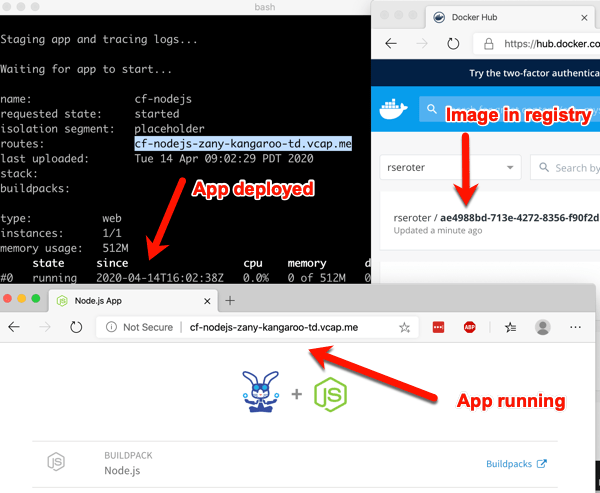

After a minute or so, you end up with a container image in whatever registry you specified (for me, Docker Hub), and a running app.

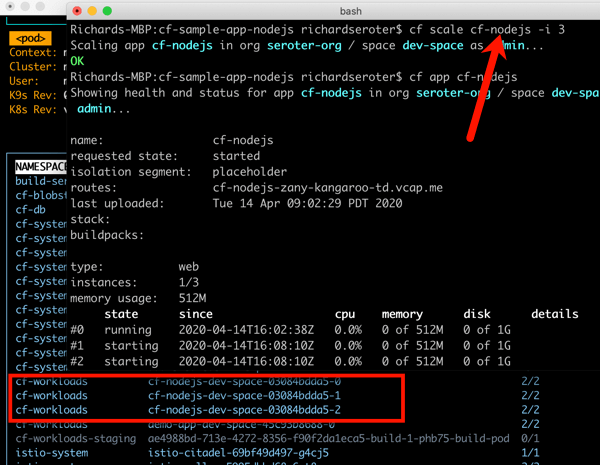

This beta release of TAS for Kubernetes also supports commands around log streaming (e.g. cf logs cf-nodejs), connecting to backing services like databases, and more. And yes, even the simple, yet powerful, cf scale command works to expand and contract pod instances.

It’s simple to uninstall the entire TAS environment from your Kubernetes cluster with a single command:

kapp delete -a cf

Thanks for trying this out with me! If you only read along, and want to try it yourself later, read the docs, download the bits, and let me know how it goes.