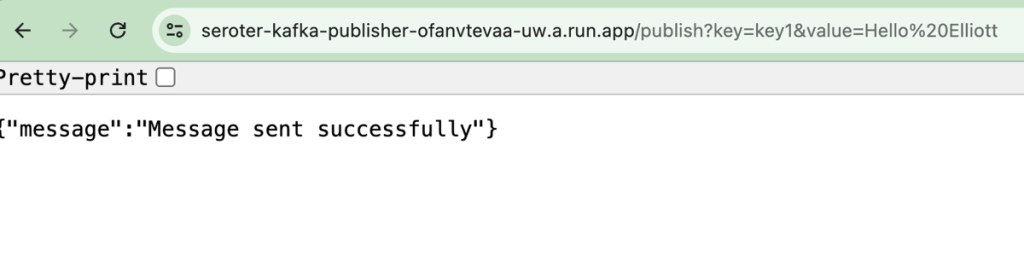

School is back in session, and I just met with a handful of teachers at a recent back-to-school night. They’re all figuring out how to account for generative AI tools that students have access to. I say, let’s give teachers the same tools to use. Specifically, what if a teacher wants a quick preliminary grade on book reports submitted by their students? To solve this, I used Gemini Flash 1.5 in Google Cloud Vertex AI in three different ways—one-off in the prompt editor, through code, and via declarative workflow.

Grade Homework in Vertex AI Studio

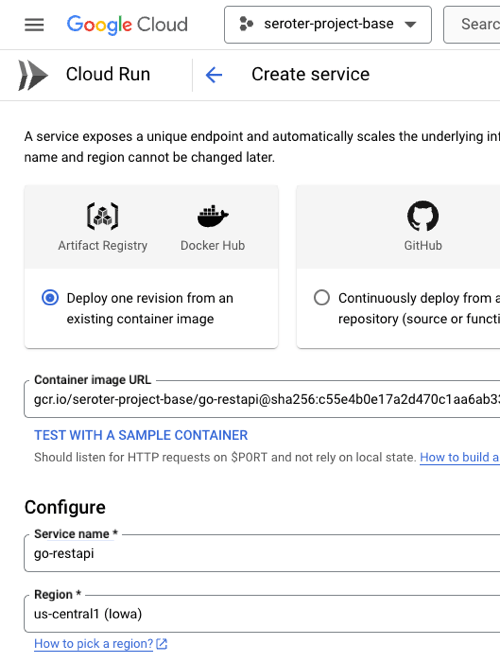

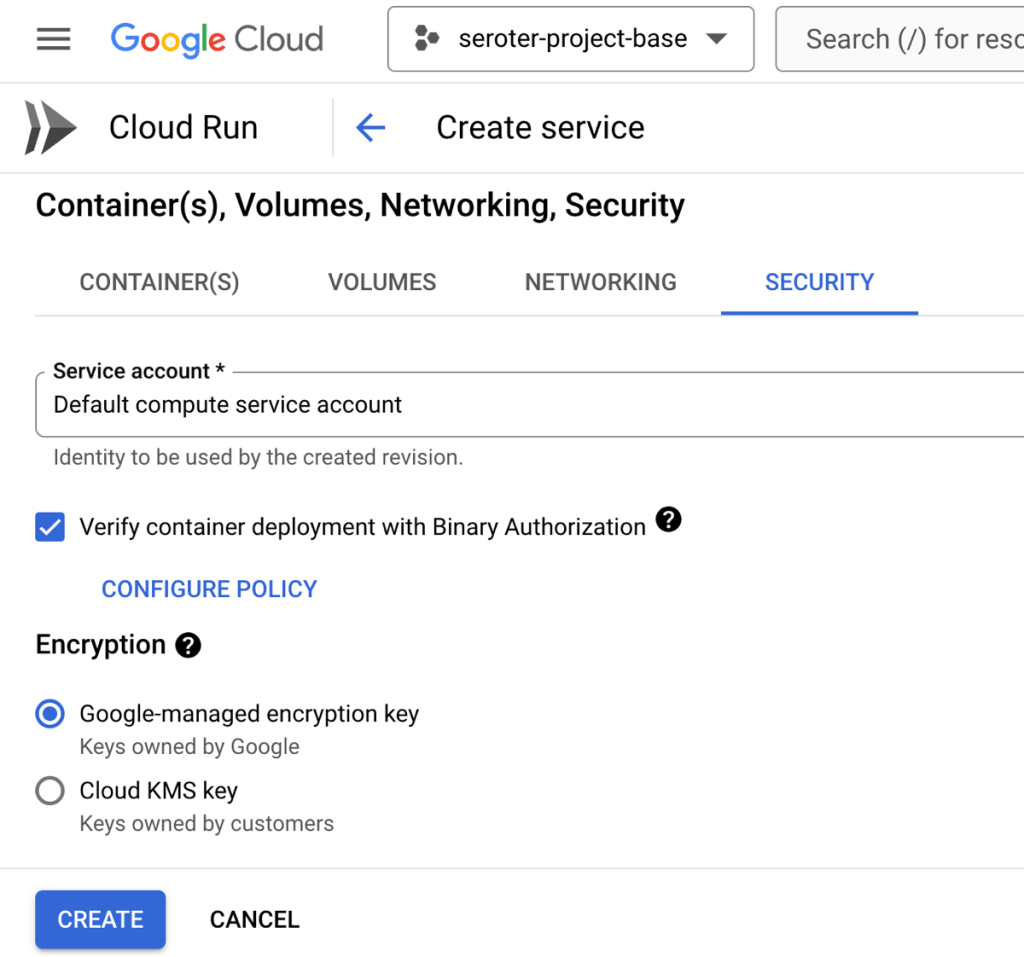

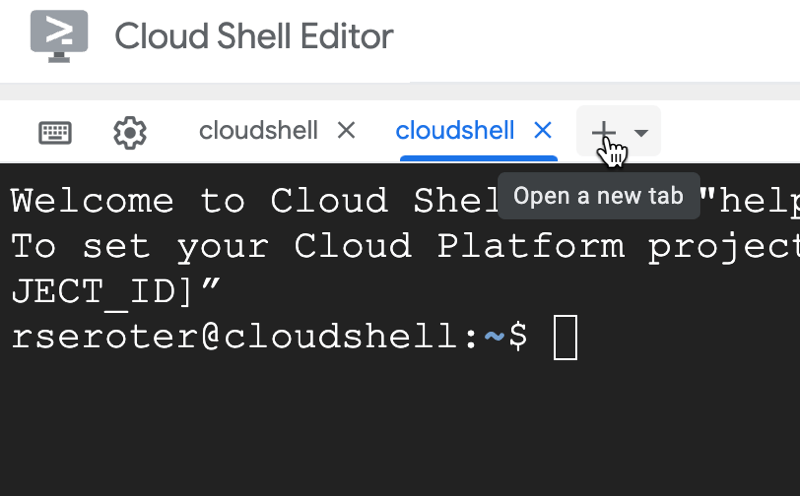

Maybe you just have one or two papers to grade. Something like Vertex AI Studio is a good choice. Even if you’re not a Google Cloud customer, you can use it for free through this link.

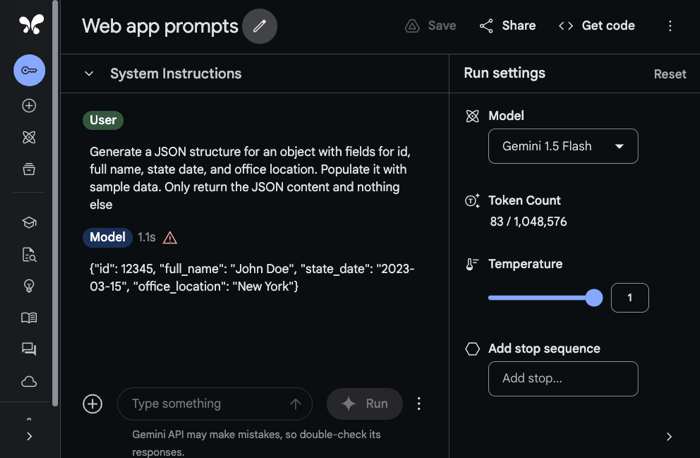

You don’t have any book reports handy to test this with? Me neither. In Vertex AI Studio, I prompted with something like “Write a 300 word book report for Pride and Prejudice from the perspective of an 8th grade student with a good vocabulary and strong writing skills.”

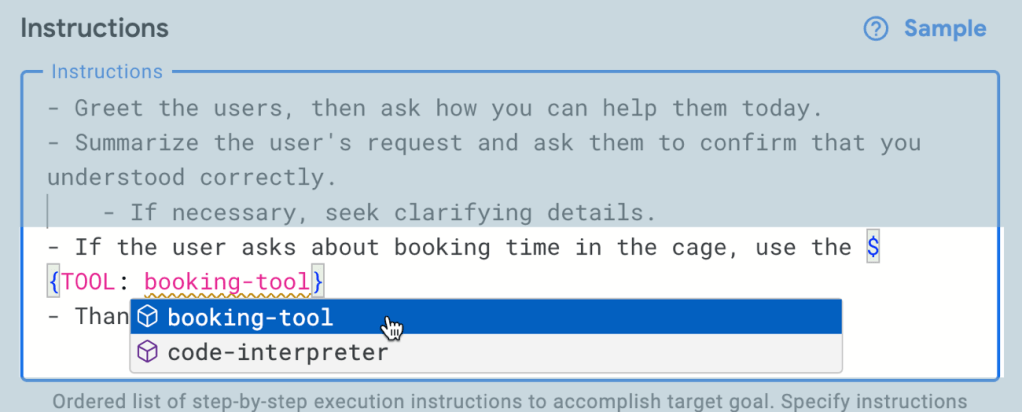

With that handy, let’s “grade” the paper. Here I’m using system instructions to direct the model. I used Gemini to generate the initial version and then I tweaked it a bit. Here’s the instructions:

Task: Evaluate 8th-grade book reports for an honors English class. You are a tough grader. Input: Book report text. Output: Initial letter grade (A, B, C, D, or F) based on: Structure: Clear introduction, body, and conclusion Grammar: Spelling, punctuation, sentence structure. Content: Understanding of the book, critical thinking. Consider: Age and language proficiency of the student.

This tells the model what to look for, the expected quality (“honors English”), and the desired output.

I added the system instructions to the marked section within Vertex AI Studio.

Then I simply pasted the book report into the “prompt” section and submitted the prompt.

I thought this was a pretty good book report, but Gemini 1.5 Flash had a high bar after obeying my system instructions.

This book report shows good understanding of the book and a strong grasp of the themes. However, there are some issues:

Structure:

The introduction is a little long and could be more concise.

The conclusion is also repetitive.

The report could benefit from more clear paragraph breaks to organize the information more effectively.

Grammar:

No significant grammar issues.

Content:

The student demonstrates good understanding of the novel's major themes and characters.

There's a strong focus on plot summary, which is okay, but the report could benefit from more critical analysis. The student needs to go beyond just describing the events to analyze how they impact the themes, characters, or messages of the book.

Overall: This report shows good effort, but it needs to be refined.

Grade: B-

If I’m a teacher, this is a fascinating way to get a preliminary assessment of a writing assignment!

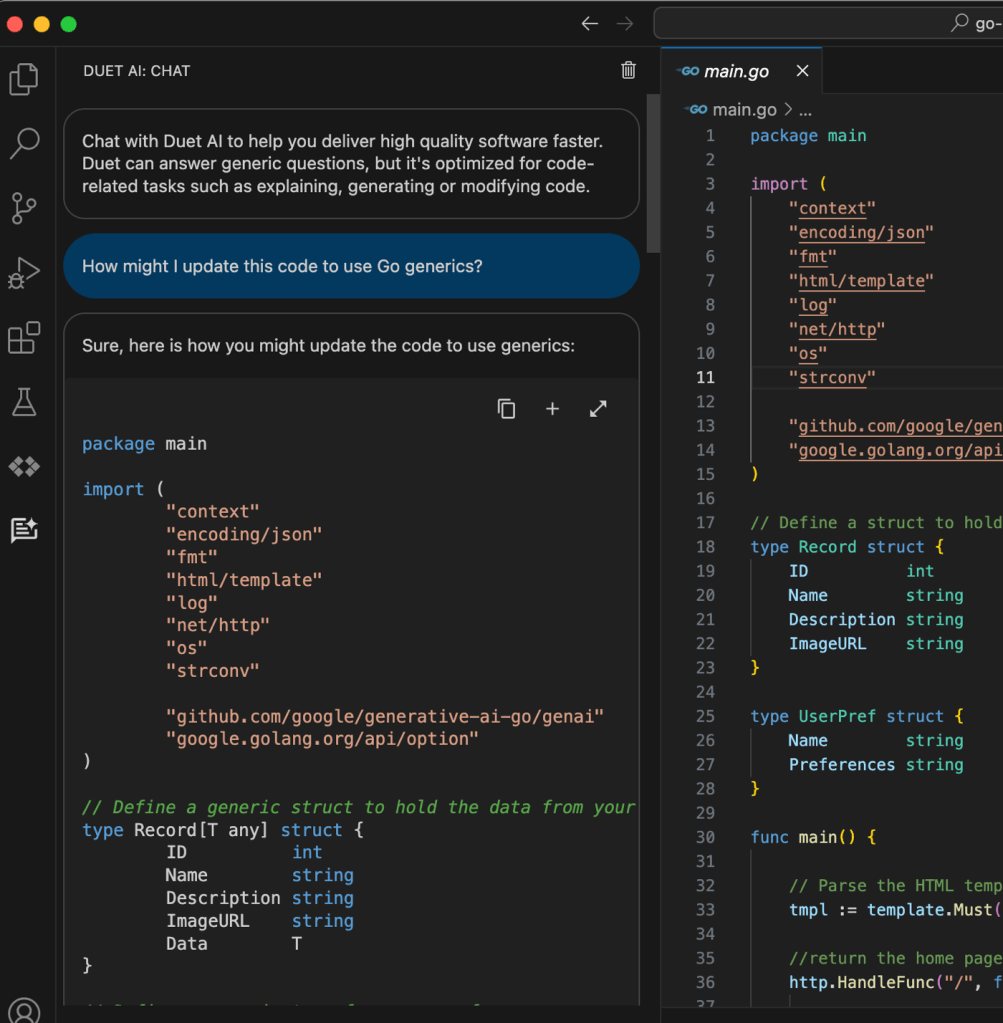

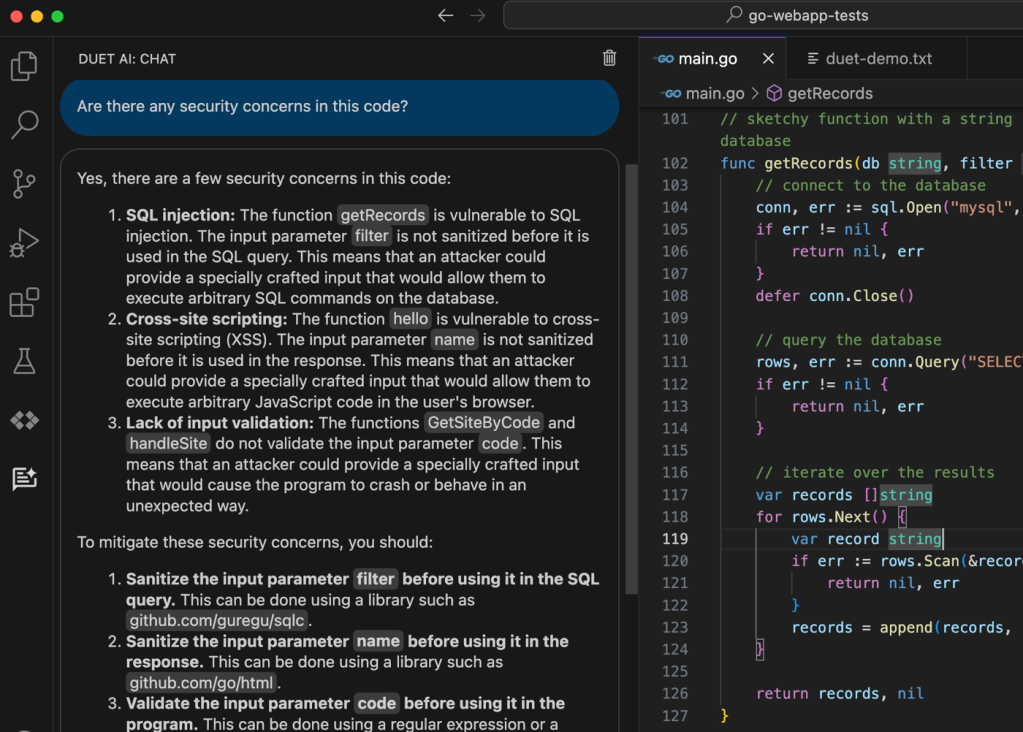

Grade Homework Through Code

The above solution works fine for one-off experiences, but how might you scale this AI-assisted grader? Another option is code.

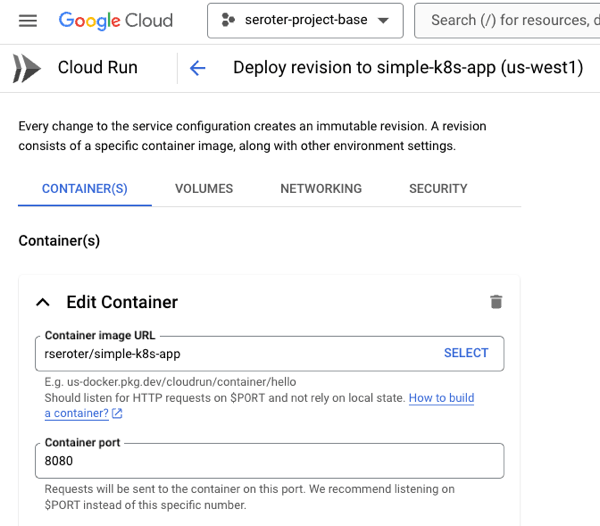

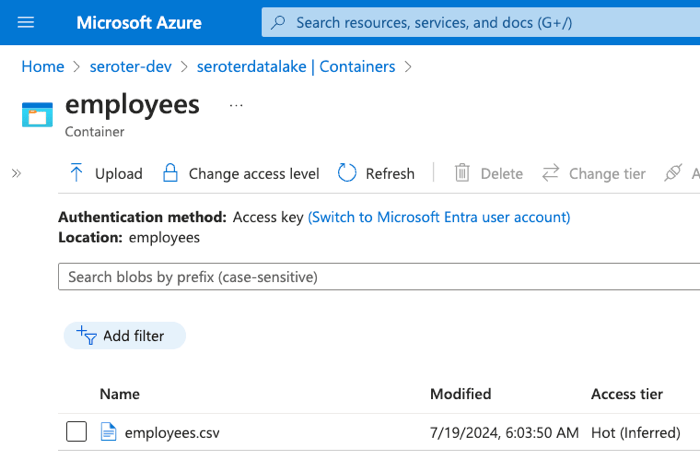

To try this scenario out, I used Cloud Firestore as my document database holding the book reports. I created a collection named “Papers” in the default database and added three documents. Each one holds a different book report.

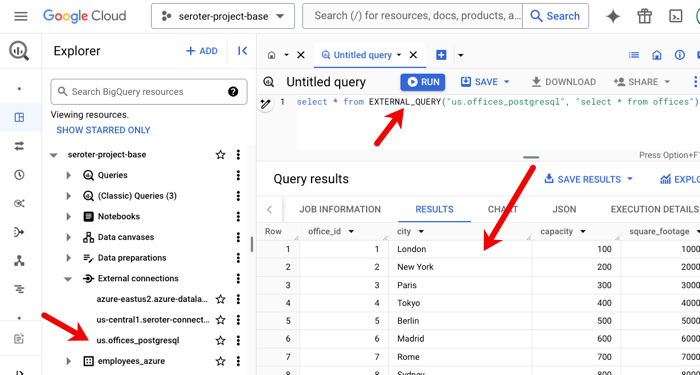

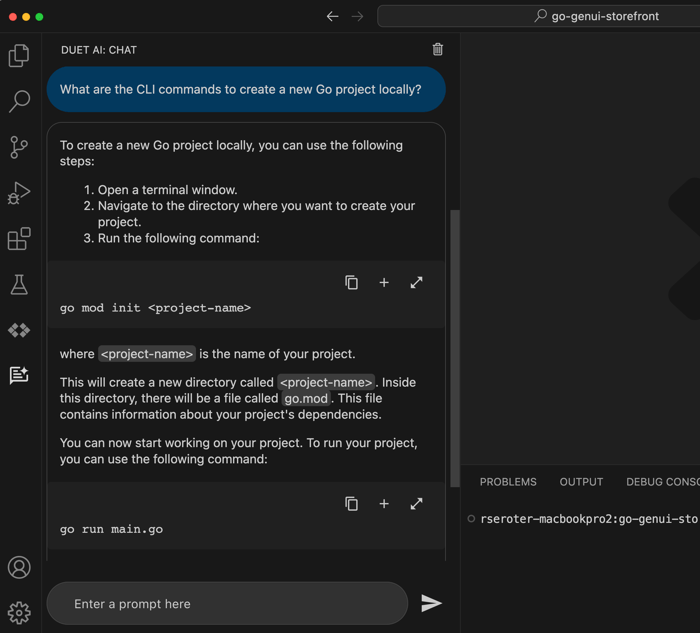

I think used the Firestore API and Vertex AI API to write some simple Go code that iterates through each Firestore document, calls Vertex AI using the provided system instructions, and then logs out the grade for each report. Note that I could have used a meta framework like LangChain, LlamaIndex, or Firebase Genkit, but I didn’t see the need.

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"log"

"os"

"cloud.google.com/go/firestore"

"cloud.google.com/go/vertexai/genai"

"google.golang.org/api/iterator"

)

func main() {

// get configuration from environment variables

projectID := os.Getenv("PROJECT_ID")

collectionName := os.Getenv("COLLECTION_NAME") // "Papers"

location := os.Getenv("LOCATION") //"us-central1"

modelName := os.Getenv("MODEL_NAME") // "gemini-1.5-flash-001"

ctx := context.Background()

//initialize Vertex AI client

vclient, err := genai.NewClient(ctx, projectID, location)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("error creating vertex client: %v\n", err)

}

gemini := vclient.GenerativeModel(modelName)

//add system instructions

gemini.SystemInstruction = &genai.Content{

Parts: []genai.Part{genai.Text(`Task: Evaluate 8th-grade book reports for an honors English class. You are a tough grader. Input: Book report text. Output: Initial letter grade (A, B, C, D, or F) based on: Structure: Clear introduction, body, and conclusion Grammar: Spelling, punctuation, sentence structure. Content: Understanding of the book, critical thinking. Consider: Age and language proficiency of the student.

`)},

}

// Initialize Firestore client

client, err := firestore.NewClient(ctx, projectID)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to create client: %v", err)

}

defer client.Close()

// Get documents from the collection

iter := client.Collection(collectionName).Documents(ctx)

for {

doc, err := iter.Next()

if err != nil {

if err == iterator.Done {

break

}

log.Fatalf("error iterating through documents: %v\n", err)

}

//create the prompt

prompt := genai.Text(doc.Data()["Contents"].(string))

//call the model and get back the result

resp, err := gemini.GenerateContent(ctx, prompt)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("error generating context: %v\n", err)

}

//print out the top candidate part in the response

log.Println(resp.Candidates[0].Content.Parts[0])

}

fmt.Println("Successfully iterated through documents!")

}

The code isn’t great, but the results were. I’m also getting more verbose responses from the model, which is cool. This is a much more scalable way to quickly grade all the homework.

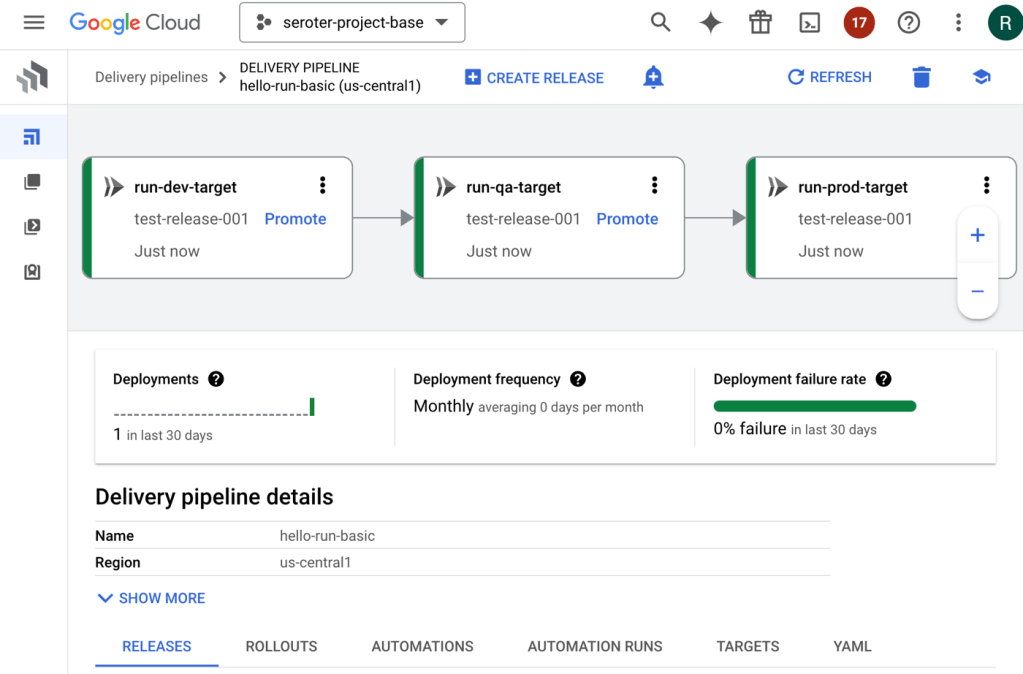

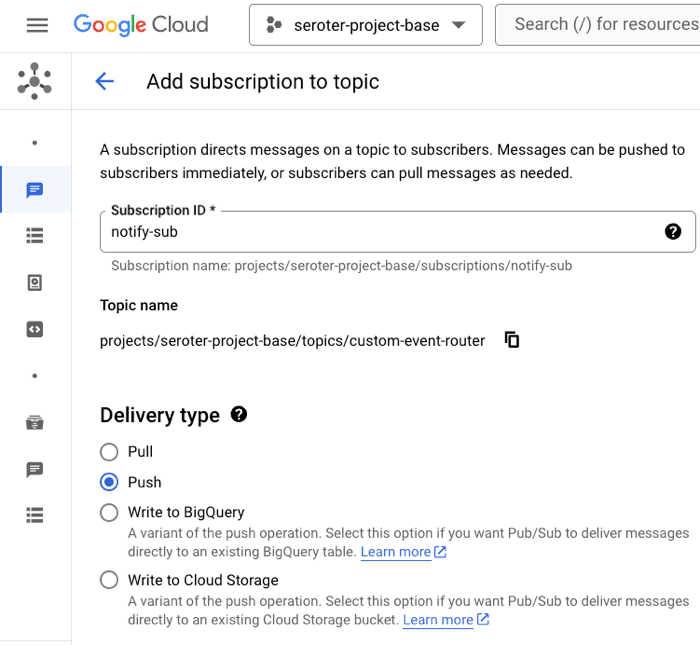

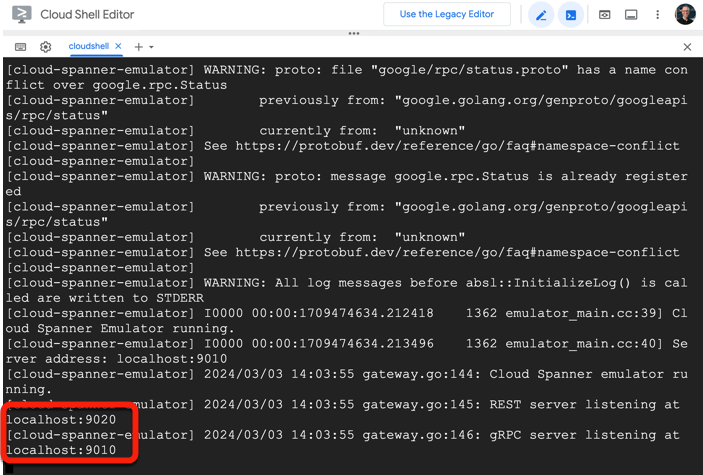

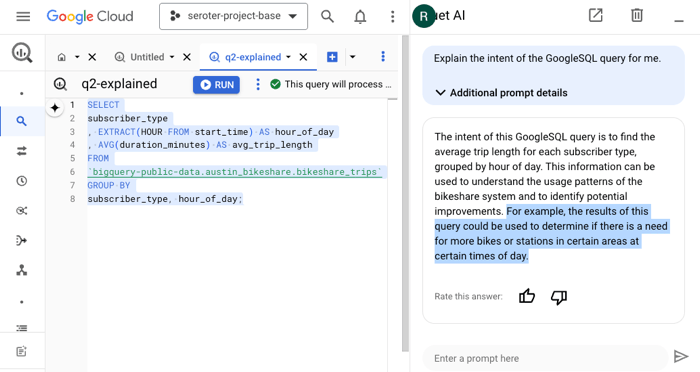

Grade Homework in Cloud Workflows

I like the code solution, but maybe I want to run this preliminary grading on a scheduled basis? Every Tuesday night? I could do that with my above code, but how about using a no-code workflow engine? Our Google Cloud Workflows product recently got a Vertex AI connector. Can I make it work with the same system instructions as the above two examples? Yes, yes I can.

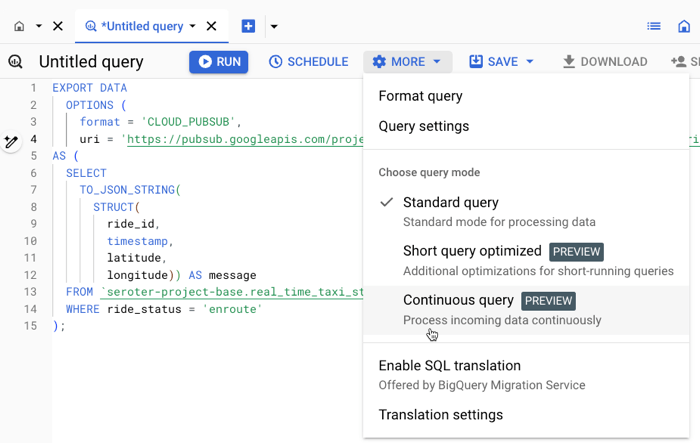

I might be the first person to stitch all this together, but it works great. I first retrieved the documents from Firestore, looped through them, and called Vertex AI with the provided system instructions. Here’s the workflow’s YAML definition:

main:

params: [args]

steps:

- init:

assign:

- collection: ${args.collection_name}

- project_id: ${args.project_id}

- location: ${args.location}

- model: ${args.model_name}

- list_documents:

call: googleapis.firestore.v1.projects.databases.documents.list

args:

collectionId: ${collection}

parent: ${"projects/" + project_id + "/databases/(default)/documents"}

result: documents_list

- process_documents:

for:

value: document

in: ${documents_list.documents}

steps:

- ask_llm:

call: googleapis.aiplatform.v1.projects.locations.endpoints.generateContent

args:

model: ${"projects/" + project_id + "/locations/" + location + "/publishers/google/models/" + model}

region: ${location}

body:

contents:

role: "USER"

parts:

text: ${document.fields.Contents.stringValue}

systemInstruction:

role: "USER"

parts:

text: "Task: Evaluate 8th-grade book reports for an honors English class. You are a tough grader. Input: Book report text. Output: Initial letter grade (A, B, C, D, or F) based on: Structure: Clear introduction, body, and conclusion Grammar: Spelling, punctuation, sentence structure. Content: Understanding of the book, critical thinking. Consider: Age and language proficiency of the student."

generation_config:

temperature: 0.5

max_output_tokens: 2048

top_p: 0.8

top_k: 40

result: llm_response

- log_file_name:

call: sys.log

args:

text: ${llm_response}

No code! I executed the workflow, passing in all the runtime arguments.

In just a moment, I saw my workflow running, and “grades” being logged to the console. In real life, I’d probably update the Firestore document with this information. I’d also use Cloud Scheduler to run this on a regular basis.

While I made this post about rescuing educators from the toil of grading papers, you can apply these patterns to all sorts of scenarios. Use prompt editors like Vertex AI Studio for experimentation and finding the right prompt phrasing. Then jump into code to interact with models in a repeatable, programmatic way. And consider low-code tools when model interactions are scheduled, or part of long running processes.