Let’s continuously deliver an ASP.NET Core app to Kubernetes using Concourse. In part one of this blog series, I showed you how to set up your environment to follow along with me. It’s easy; just set up Azure Container Registry, Azure Storage, Azure Kubernetes Service, and Concourse. In this post, we’ll start our pipeline by pulling source code, running unit tests, generating a container image that’s stored in Azure Container Registry, and generating a tarball for Azure Blob Storage.

We’re building this pipeline with Concourse. Concourse has three core primitives: tasks, jobs, and resources. Tasks form jobs, jobs form pipelines, and state is stored in resources. Concourse is essentially stateless, meaning there are no artifacts on the server after a build. You also don’t register any plugins or extensions. Rather, the pipeline is executed in containers that go away after the pipeline finishes. Any state — be it source code or Docker images — resides in durable resources, not Concourse itself.

Let’s start building a pipeline.

Pulling source code

A Concourse pipeline is defined in YAML. Concourse ships with a handful of “known” resource types including Amazon S3, git, and Cloud Foundry. There are dozens and dozens of community ones, and it’s not hard to build your own. Because my source code is stored in GitHub, I can use the out-of-the-box resource type for git.

At the top of my pipeline, I declared that resource.

---

resources:

- name: source-code

type: git

icon: github-circle

source:

uri: https://github.com/rseroter/seroter-api-k8s

branch: master

I’ve gave the resource a name (“source-code”) and identified where the code lives. That’s it! Note that when you deploy a pipeline, Concourse produces containers that “check” resources on a schedule for any changes that should trigger a pipeline.

Running unit tests

Next up? Build a working version of a pipeline that does something. Specifically, it should execute unit tests. That means we need to define a job.

A job has a build plan. That build plan contains any of three things: get steps (to retrieve a resource), put steps (to push something to a resource), and task steps (to run a script). Our job below has one get step (to retrieve source code), and one task (to execute the xUnit tests).

jobs:

- name: run-unit-tests

plan:

- get: source-code

trigger: true

- task: first-task

config:

platform: linux

image_resource:

type: docker-image

source: {repository: mcr.microsoft.com/dotnet/core/sdk}

inputs:

- name: source-code

run:

path: sh

args:

- -exec

- |

dotnet test ./source-code/seroter-api-k8s/seroter-api-k8s.csproj

Let’s break it down. First, my “plan” gets the source-code resource. And because I set “trigger: true” Concourse will kick off this job whenever it detects a change in the source code.

Next, my build plan has a “task” step. Tasks run in containers, so you need to choose a base image that runs the user-defined script. I chose the Microsoft-provided .NET Core image so that I’d be confident it had all the necessary .NET tooling installed. Note that my task has an “input.” Since tasks are like functions, they have inputs and outputs. Anything I input into the task is mounted into the container and is available to any scripts. So, by making the source-code an input, my shell script can party on the source code retrieved by Concourse.

Finally, I embedded a short script that invokes the “dotnet test” command. If I were being responsible, I’d refactor this embedded script into an external file and reference that file. But hey, this is easier to read.

This is now a valid pipeline. In the previous post, I had you install the fly CLI to interact with Concourse. From the fly CLI, I deploy pipelines with the following command:

fly -t rs set-pipeline -c azure-k8s-rev1.yml -p azure-k8s-rev1

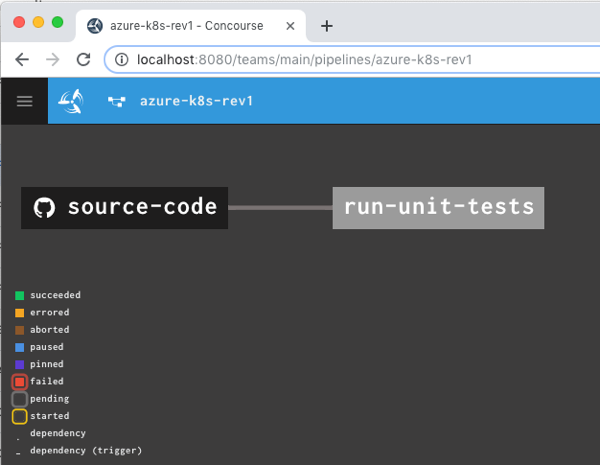

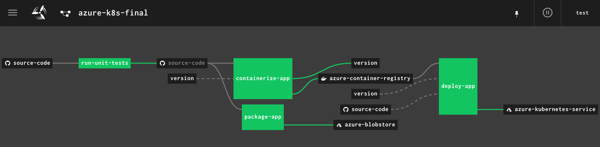

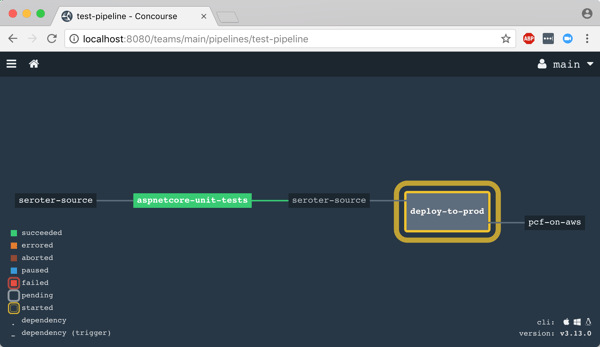

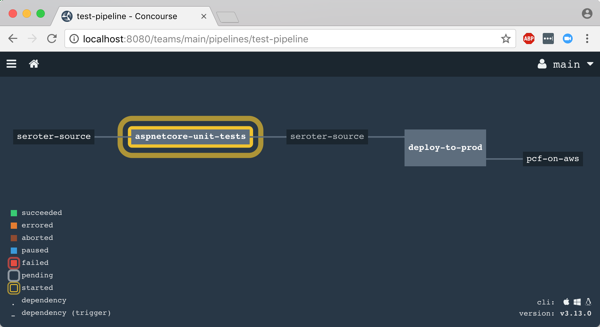

That command says to use the “rs” target (which points to a given Concourse instance), use the YAML file holding the pipeline, and name this pipeline azure-k8s-rev1. It deployed instantly, and looked like this in the Concourse web dashboard.

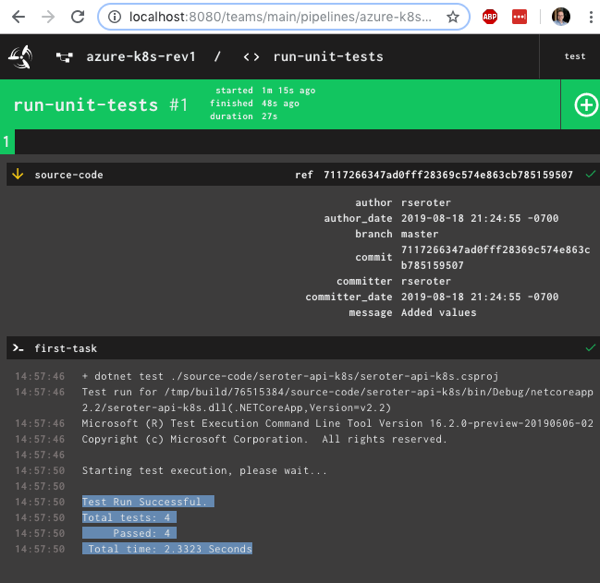

After unpausing the pipeline so that it came alive, I saw the “run unit tests” job start running. It’s easy to view what a job is doing, and I saw that it loaded the container image from Microsoft, mounted the source code, ran my script and turned “green” because all my tests passed.

Nice! I had a working pipeline. Now to generate a container image.

Producing and publishing a container image

A pipeline that just run tests is kinda weird. I need to do something when tests pass. In my case, I wanted to generate a Docker image. Another of the built-in Concourse resource types is “docker-image” which generates a container image and puts it into a registry. Here’s the resource definition that worked with Azure Container Registry:

resources:

- name: source-code

[...]

- name: azure-container-registry

type: docker-image

icon: docker

source:

repository: myrepository.azurecr.io/seroter-api-k8s

tag: latest

username: ((azure-registry-username))

password: ((azure-registry-password))

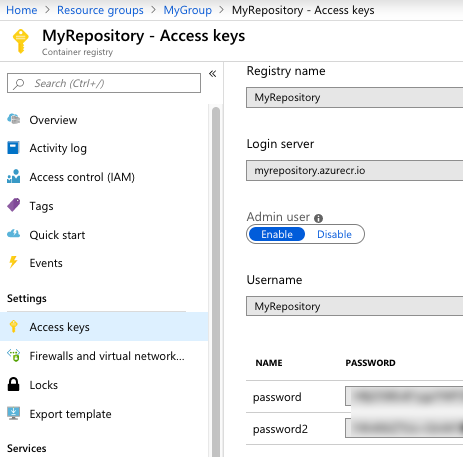

Where do you get those Azure Container Registry values? From the Azure Portal, they’re visible under “Access keys.” I grabbed the Username and one of the passwords.

Next, I added a new job to the pipeline.

jobs:

- name: run-unit-tests

[...]

- name: containerize-app

plan:

- get: source-code

trigger: true

passed:

- run-unit-tests

- put: azure-container-registry

params:

build: ./source-code

tag_as_latest: true

What’s this job doing? Notice that I “get” the source code again. I also set a “passed” attribute meaning this will only run if the unit test step completes successfully. This is how you start chaining jobs together into a pipeline! Then I “put” into the registry. Recall from the first blog post that I generated a Dockerfile from within Visual Studio for Mac, and here, I point to it. The resource does a “docker build” with that Dockerfile, tags the resulting image as the “latest” one, and pushes to the registry.

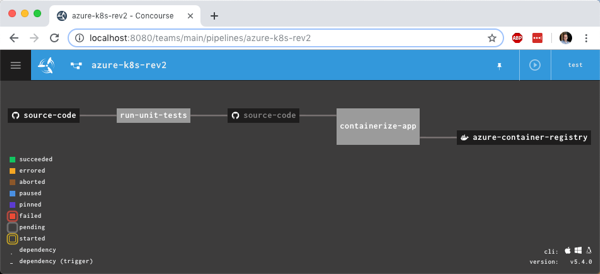

I pushed this as a new pipeline to Concourse:

fly -t rs set-pipeline -c azure-k8s-rev2.yml -p azure-k8s-rev2

I now had something that looked like a pipeline.

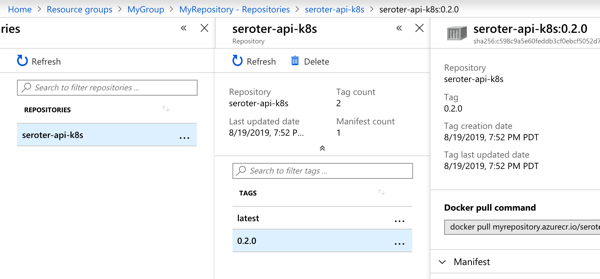

I manually triggered the “run unit tests” job, and after it completed, the “containerize app” job ran. When that was finished, I checked Azure Container Registry and saw a new repository one with image in it.

Generating and storing a tarball

Not every platform wants to run containers. BLASPHEMY! BURN THE HERETIC! Calm down. Some platforms happily take your source code and run it. So our pipeline should also generate a single artifact with all the published ASP.NET Core files.

I wanted to store this blob in Azure Storage. Since Azure Storage isn’t a built-in Concourse resource type, I needed to reference a community one. No problem finding one. For non-core resources, you have to declare the resource type in the pipeline YAML.

resource_types:

- name: azure-blobstore

type: docker-image

source:

repository: pcfabr/azure-blobstore-resource

A resource type declaration is fairly simple; it’s just a type (often docker-image) and then the repo to get it from.

Next, I needed the standard resource definition. Here’s the one I created for Azure Storage:

name: azure-blobstore

type: azure-blobstore

icon: azure

source:

storage_account_name: ((azure-storage-account-name))

storage_account_key: ((azure-storage-account-key))

container: coreapp

versioned_file: app.tar.gz

Here the “type” matches the resource type name I set earlier. Then I set the credentials (retrieved from the “Access keys” section in the Azure Portal), container name (pre-created in the first blog post), and the name of the file to upload. Regex is supported here too.

Finally, I added a new job that takes source code, runs a “publish” command, and creates a tarball from the result.

jobs:

- name: run-unit-tests

[...]

- name: containerize-app

[...]

- name: package-app

plan:

- get: source-code

trigger: true

passed:

- run-unit-tests

- task: first-task

config:

platform: linux

image_resource:

type: docker-image

source: {repository: mcr.microsoft.com/dotnet/core/sdk}

inputs:

- name: source-code

outputs:

- name: compiled-app

- name: artifact-repo

run:

path: sh

args:

- -exec

- |

dotnet publish ./source-code/seroter-api-k8s/seroter-api-k8s.csproj -o .././compiled-app

tar -czvf ./artifact-repo/app.tar.gz ./compiled-app

ls

- put: azure-blobstore

params:

file: artifact-repo/app.tar.gz

Note that this job is also triggered when unit tests succeed. But it’s not connected to the containerization job, so it runs in parallel. Also note that in addition to an input, I also have outputs defined on the task. This generates folders that are visible to subsequent steps in the job. I dropped the tarball into the “artifact-repo” folder, and then “put” that file into Azure Blob Storage.

I deployed this pipeline as yet another revision:

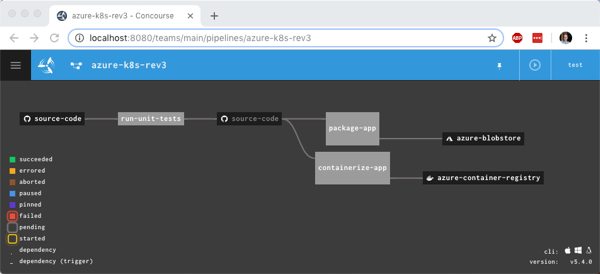

fly -t rs set-pipeline -c azure-k8s-rev3.yml -p azure-k8s-rev3

Now this pipeline’s looking pretty hot. Notice that I have parallel jobs that fire after I run unit tests.

I once again triggered the unit test job, and watched the subsequent jobs fire. After the pipeline finished, I had another updated container image in Azure Container Registry and a file sitting in Azure Storage.

Adding semantic version to the container image

I could stop there and push to Kubernetes (next post!), but I wanted to do one more thing. I don’t like publishing Docker images with the “latest” tag. I want a real version number. It makes sense for many reasons, not the least of which is that Kubernetes won’t pick up changes to a container if the tag doesn’t change! Fortunately, Concourse has a default resource type for semantic versioning.

There are a few backing stores for the version number. Since Concourse is stateless, we need to keep the version value outside of Concourse itself. I chose a git backend. Specifically, I added a branch named “version” to my GitHub repo, and added a single file (no extension) named “version”. I started the version at 0.1.0.

Then, I ensured that my GitHub account had an SSH key associated with it. I needed this so that Concourse could write changes to this version file sitting in GitHub.

I added a new resource to my pipeline definition, referencing the built-in semver resource type.

- name: version

type: semver

source:

driver: git

uri: git@github.com:rseroter/seroter-api-k8s.git

branch: version

file: version

private_key: |

-----BEGIN OPENSSH PRIVATE KEY-----

[...]

-----END OPENSSH PRIVATE KEY-----

In that resource definition, I pointed at the repo URI, branch, file name, and embedded the private key for my account.

Next, I updated the existing “containerization” job to get the version resource, use it, and then update it.

jobs:

- name: run-unit-tests

[...]

- name: containerize-app

plan:

- get: source-code

trigger: true

passed:

- run-unit-tests

- get: version

params: {bump: minor}

- put: azure-container-registry

params:

build: ./source-code

tag_file: version/version

tag_as_latest: true

- put: version

params: {file: version/version}

- name: package-app

[...]

First, I added another ‘get” for version. Notice that its parameter increments the number by one minor version. Then, see that the “put” for the container registry uses “version/version” as the tag file. This ensures our Docker image is tagged with the semantic version number. Finally, notice I “put” the incremented version file back into GitHub after using it successfully.

I deployed a fourth revision of this pipeline using this command:

fly -t rs set-pipeline -c azure-k8s-rev4.yml -p azure-k8s-rev4

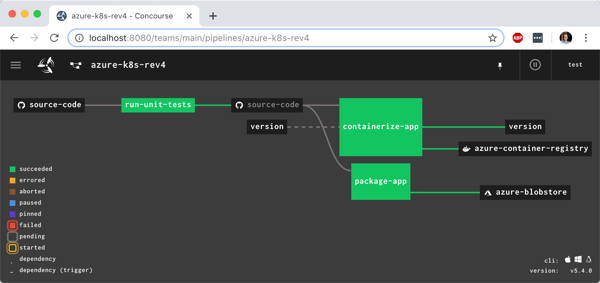

You see the pipeline, post-execution, below. The “version” resource comes into and out of the “containerize app” job.

With the pipeline done, I saw that the “version” value in GitHub was incremented by the pipeline, and most importantly, our Docker image has a version tag.

In this blog post, we saw how to gradually build up a pipeline that retrieves source and prepares it for downstream deployment. Concourse is fun and easy to use, and its extensibility made it straightforward to deal with managed Azure services. In the final blog post of this series, we’ll take pipeline-generated Docker image and deploy it to Azure Kubernetes Service.

What a fun year. Lots of things to be grateful for. Took on some more responsibility at

What a fun year. Lots of things to be grateful for. Took on some more responsibility at