Serverless things don’t always complete their work in milliseconds. With the introduction of AWS Step Functions and Azure Durable Functions, we have compute instances that exist for hours, days, or even months. With serverless workflow tools like Azure Logic Apps, it’s also easy to build long-running processes. So in this world of continuous delivery and almost-too-easy update processes, what happens when you update the underlying definition of things that have running instances? Do they use the version they started with? Do they pick up changes and run with those after waking up? Do they crash and cause the heat death of the universe? I was curious, so I tried it out.

Azure Durable Functions

Azure Durable Functions extends “regular” Azure Functions. They introduce a stateful processing layer by defining an “orchestrator” that calls Azure Functions, checkpoints progress, and manages intermediate state.

Let’s build one, and then update it to see what happens to the running instances.

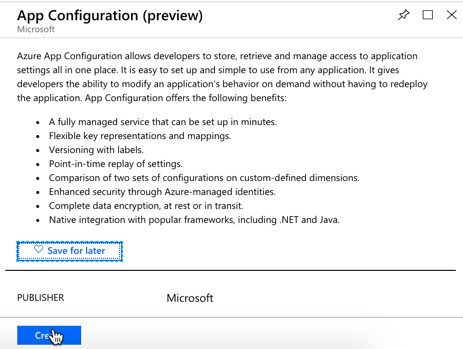

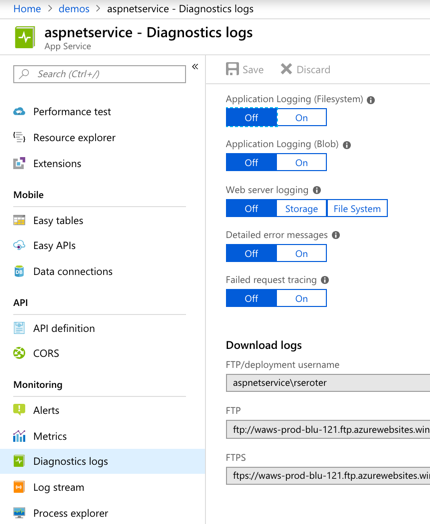

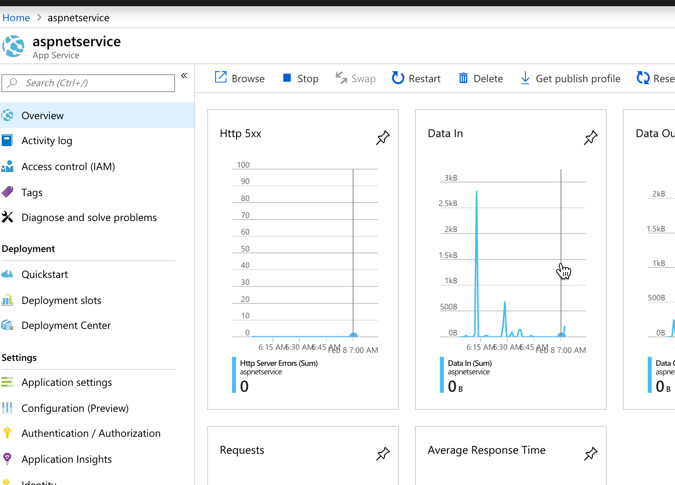

First, I created a new Function App in the Azure Portal. A Function App holds individual functions. This one uses the “consumption plan” so I only pay for the time a function runs, and contains .NET-based functions. Also note that it provisions a storage account, which we’ll end up using for checkpointing.

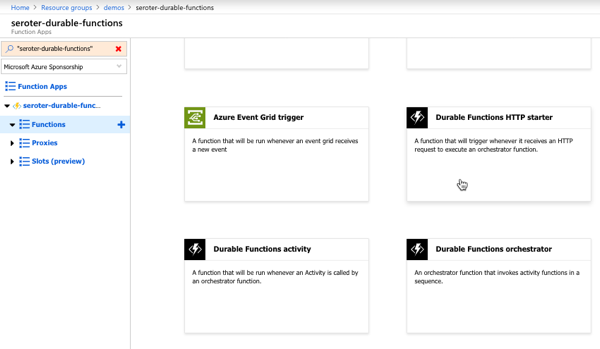

Durable Functions are made up of a client function that create an orchestration, orchestration functions that coordinate work, and activity functions that actually do the work. From the Azure Portal, I could see a template for creating an HTTP client (or starter) function.

The function code generated by the template works as-is.

#r "Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Extensions.DurableTask"

#r "Newtonsoft.Json"

using System.Net;

public static async Task<HttpResponseMessage> Run(

HttpRequestMessage req,

DurableOrchestrationClient starter,

string functionName,

ILogger log)

{

// Function input comes from the request content.

dynamic eventData = await req.Content.ReadAsAsync<object>();

// Pass the function name as part of the route

string instanceId = await starter.StartNewAsync(functionName, eventData);

log.LogInformation($"Started orchestration with ID = '{instanceId}'.");

return starter.CreateCheckStatusResponse(req, instanceId);

}

Next I created the activity function. Like with the client function, the Azure Portal generates a working function from the template. It simply takes in a string, and returns a polite greeting.

#r "Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Extensions.DurableTask"

public static string Run(string name)

{

return $"Hello {name}!";

}

The final step was to create the orchestrator function. The template-generated code is below. Notice that our orchestrator calls the “hello” function three times with three different inputs, and aggregates the return values into a single output.

#r "Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Extensions.DurableTask"

public static async Task<List<string>> Run(DurableOrchestrationContext context)

{

var outputs = new List<string>();

outputs.Add(await context.CallActivityAsync<string>("Hello", "Tokyo"));

outputs.Add(await context.CallActivityAsync<string>("Hello", "Seattle"));

outputs.Add(await context.CallActivityAsync<string>("Hello", "London"));

// returns ["Hello Tokyo!", "Hello Seattle!", "Hello London!"]

return outputs;

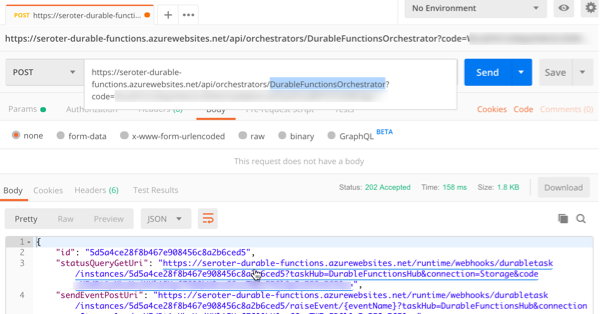

After saving this function, I went back to the starter/client function and clicked the “Get function URL” link to get the URL I need to invoke to instantiate this orchestrator. Then, I plugged that into Postman, and submitted a POST request.

Since the Durable Function is working asynchronously, I get back URIs to check the status, or terminate the orchestrator. I invoked the “get status” endpoint, and saw the aggregated results returned from the orchestrator function.

So it all worked. Terrific. Next I wanted to add a delay in between activity function calls to simulate a long-running process. What’s interesting with Durable Functions is that every time it gets results back from an async call (or timer), it reruns the entire orchestrator from scratch. Now, it checks the execution log to avoid calling the same operation again, but this made me wonder how it would respond if I added *new* activities in the mix, or deleted activities.

First, I added some instrumentation to the orchestrator function (and injected function input) so that I could see more about what was happening. In the code below, if we’re not replaying activities (so, first time it’s being called), it traces out a message.

public static async Task<List<string>> Run(DurableOrchestrationContext context, ILogger log)

{

var outputs = new List<string>();

outputs.Add(await context.CallActivityAsync<string>("Hello", "Tokyo"));

if (!context.IsReplaying) log.LogInformation("Called function once.");

outputs.Add(await context.CallActivityAsync<string>("Hello", "Seattle"));

if (!context.IsReplaying) log.LogInformation("Called function twice.");

outputs.Add(await context.CallActivityAsync<string>("Hello", "London"));

if (!context.IsReplaying) log.LogInformation("Called function thrice.");

// returns ["Hello Tokyo!", "Hello Seattle!", "Hello London!"]

return outputs;

}

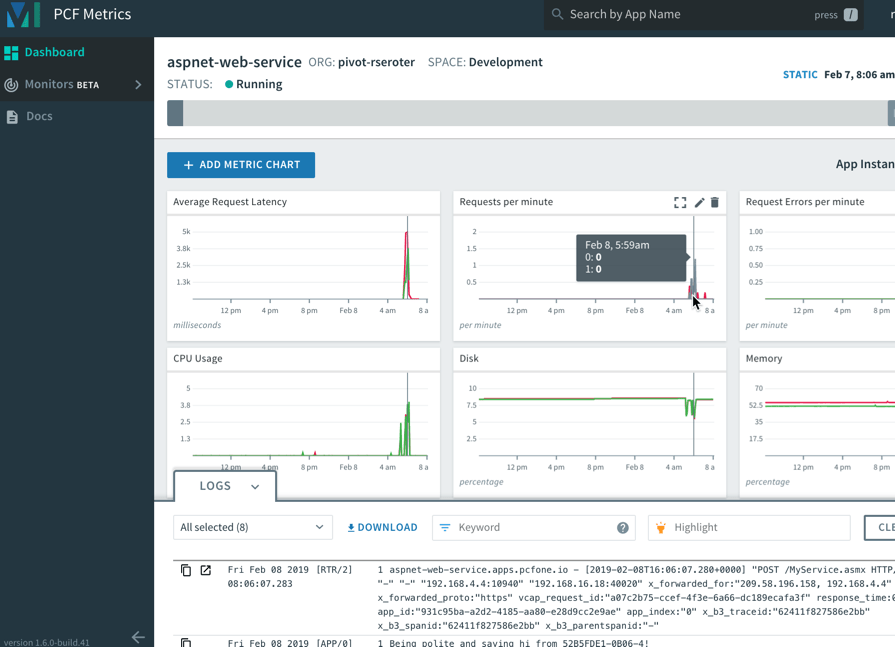

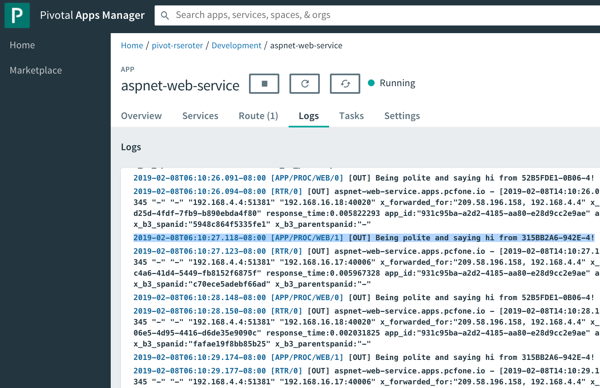

After saving this update, I triggered the client function again, and with the streaming “Logs” view open in the Portal. Here, I saw trace statements for each call to an activity function.

A durable function supports Timers that pause processing for up to seven days. I added the following code between the second and third function calls. This pauses the function for 30 seconds.

if (!context.IsReplaying) log.LogInformation("Starting delay.");

DateTime deadline = context.CurrentUtcDateTime.Add(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(30));

await context.CreateTimer(deadline, System.Threading.CancellationToken.None);

if (!context.IsReplaying) log.LogInformation("Delay finished.");

If you trigger the client function again, it will take 30-ish seconds to get results back, as expected.

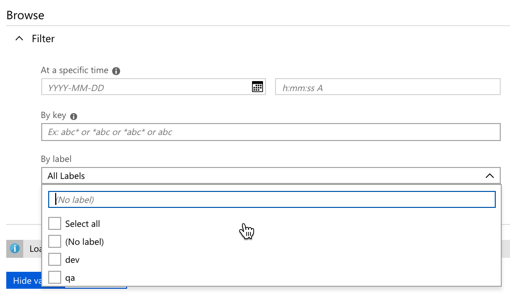

Next I tested three scenarios to see how Durable Functions handled them:

- Wait until the orchestrator hits the timer, and change the payload for an activity function call that executed before the timer started. What happens when the framework tries to re-run a step that’s changed? I changed the first function’s payload from “Tokyo” to “Mumbai” after the function instance had already passed the first call, and was paused at the timer. After the function resumed from the timer, the orchestrator failed with a message of: “Non-Deterministic workflow detected: TaskScheduledEvent: 0 TaskScheduled Hello.” Didn’t like that. Changing the call signature, or apparently even the payload is a no-no if you don’t want to break running instances.

- Wait until the orchestrator hits the timer, and update the function to introduce a new activity function call in code above the timer. Does the framework execute that new function call when it wakes up and re-runs, or ignore it? Indeed, it runs it. So after the timer wrapped up, the NEW, earlier function call got invoked, AND it ran the timer again before continuing. That part surprised me, and it only kinda worked. Instead of returning the expected value from the activity function, I got a “2” back. And some times when I tested this, I got the above “non-deterministic workflow” error. So, your mileage may vary.

- Add an activity call after the timer, and see if it executes it after the delay is over. Does the orchestrator “see” the new activity call I added to the code after it woke back up? The first time I tried this, I again got the “non-deterministic workflow” error, but with a few more tests, I saw it actually executed the new function after waking back up, AND running the timer a second time.

What have we learned? The “version” a Durable Function starts with isn’t serialized and used for the entirety of the execution. It’s picking up things changing along the way. Be very aware of side effects! For a number of these tests, I also had to “try again” and would see different results. I feel like I was breaking Azure Functions!

What’s the right way to version these? Microsoft offers some advice, which ranges from “do nothing and let things fail” to “deploy an entirely new function.” But from these tests, I’d advise against changing function definitions outside of explicitly deploying new versions.

Azure Logic Apps

Let’s take a look at Logic Apps. This managed workflow service is designed for constructing processes that integrate a variety of sources and targets. It supports hundreds of connectors to things likes Salesforce.com, Amazon Redshift, Slack, OneDrive, and more. A Logic App can run for 90 days in the multi-tenant environment, and up to a year in the dedicated environment. So, most users of Logic Apps are going to have instances in-flight when it comes time to deploy updates.

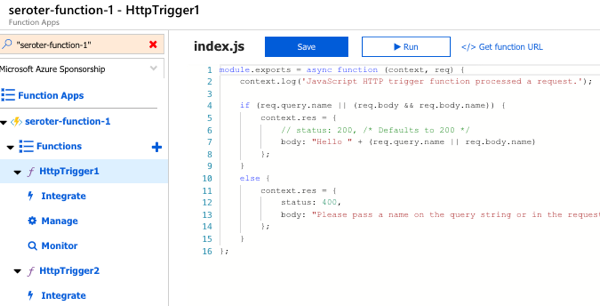

To test this out, I first created a couple of Azure Functions that Logic Apps could call. These JavaScript functions are super lame, and just return a greeting.

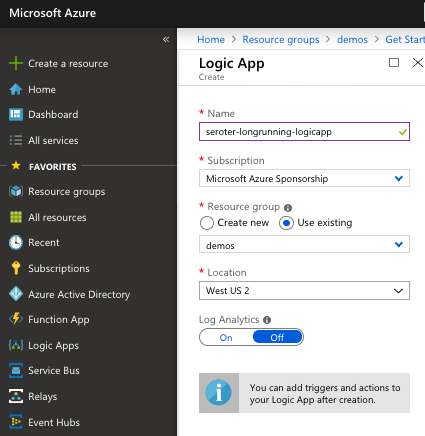

Next up, I created a Logic App. It’s easy.

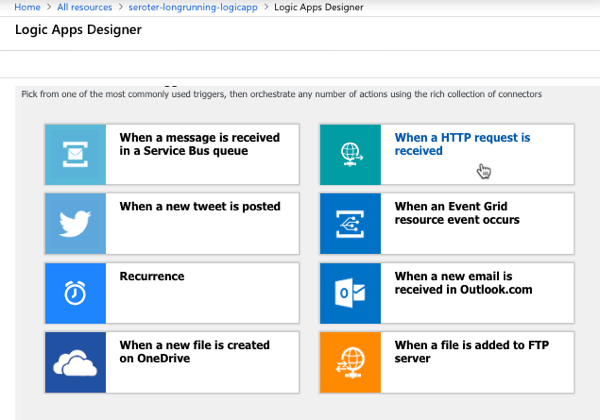

After a few moments, I could jump in and start designing my workflow. As a “serverless” service, Logic Apps only run when invoked, and start with a trigger. I chose the HTTP trigger.

My Logic App takes in an HTTP request, has a 45 second “delay” (which could represent waiting for new input, or a long-running API call) before invoke our simple Azure Function.

I saved the Logic App, called the HTTP endpoint via Postman, and waited. After about 45 seconds, I saw that everything succeeded.

Next, I kicked off another instance, and quickly went in and added another Function call after the first one. What would Logic Apps do with that after the delay was over? It ignored the new function call. Then I kicked off another Logic Apps instance, and quickly deleted the second function call. Would the instance wake up and now only call one Function? Nope, it called them both.

So it appears that Logic Apps snapshot the workflow when it starts, and it executes that version, regardless of what changes in the underlying definition after the fact. That seems good. It results in a more consistent, predictable process. Logic Apps does have the concept of versioning, and you can promote previous versions to the active one as needed.

AWS Step Functions

AWS doesn’t have something exactly like Logic Apps, but AWS Step Functions is somewhat similar to Azure Durable Functions. With Step Functions, you can chain together a series of AWS services into a workflow. It basically builds a state machine that you craft in their JSON-based Amazon State Language. A given Step Function can be idle for up to a year, so again. you’ll probably have long-running instances going at all times!

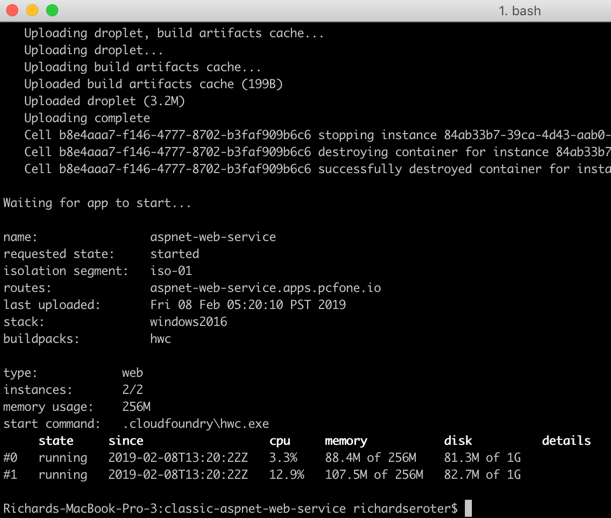

I jumped into the AWS console and started with their “hello world” template.

This state machine has a couple basic states that execute immediately. Then I added a 20 second wait.

After deploying the Step Function, it was easy to see that it ran everything quickly and successfully.

Next, I kicked off a new instance, and added a new step to the state machine while the instance was waiting. The Step Function that was running ignored it.

When I kicked off another Step Function and removed the step after the wait step, it also ignored it. It seems pretty clear that AWS Step Functions snapshot the workflow at the start proceed with that snapshot, even if the underlying definition changes. I didn’t find much documentation around formally versioning Step Functions, but it seems to keep you fairly safe from side effects.

With all of these, it’s important to realize that you also have to consider versioning of downstream calls. I could have an unchanged Logic App, but the function or API it invokes had its plumbing entirely updated after the Logic App started running. There’s no way to snapshot the state of all the dependencies! That’s normal in a distributed system. But, something to remember.

Have you observed any different behavior with these stateful serverless products?

What a fun year. Lots of things to be grateful for. Took on some more responsibility at

What a fun year. Lots of things to be grateful for. Took on some more responsibility at