I’ll admit it, I’m a PaaS guy. Platform-as-a-Service is an ideal abstraction for those that don’t get joy from fiddling with infrastructure. From Google App Engine, to Heroku, to Cloud Foundry, I’ve appreciated attempts to deliver runtimes that makes it easier to ship and run code. Classic PaaS-type services were great at what they did. The problem with all of them—this includes all the first generation serverless products like Amazon Lambda—were that they were limited. Some of the necessary compromises were well-meaning and even healthy: build 12-factor apps, create loose coupling, write less code and orchestrate manage services instead. But in the end, all these platforms, while successful in various ways, were too constrained to take on a majority of apps for a majority of people. Times have changed.

Google Cloud Run started as a serverless product, but it’s more of an application platform at this point. It’s reminiscent of a PaaS, but much better. While not perfect for everything—don’t bring Windows apps, always-on background components, or giant middleware—it’s becoming my starting point for nearly every web app I build. There are ten reasons why Cloud Run isn’t limited by PaaS-t constraints, is suitable for devs at every skill level, and can run almost any web app.

- It’s for functions AND apps.

- You can run old AND new apps.

- Use by itself AND as part of a full cloud solution.

- Choose simple AND sophisticated configurations.

- Create public AND private services.

- Scale to zero AND scale to 1.

- Do one-off deploys AND set up continuous delivery pipelines.

- Own aspects of security AND offload responsibility.

- Treat as post-build target AND as upfront platform choice.

- Rely on built-in SLOs, logs, metrics AND use your own observability tools.

Let’s get to it.

#1. It’s for functions AND apps.

Note that Cloud Run also has “jobs” for run-to-completion batch work. I’m focusing solely on Cloud Run web services here.

I like “functions.” Write short code blocks that respond to events, and perform an isolated piece of work. There are many great uses cases for this.

The new Cloud Run functions experience makes it easy to bang out a function in minutes. It’s baked into CLI and UI. Once I decide to create a function ….

I only need to pick a service name, region, language runtime, and whether access to this function is authenticated or not.

Then, I see a browser-based editor where I can write, test, and deploy my function. Simple, and something most of us equate with “serverless.”

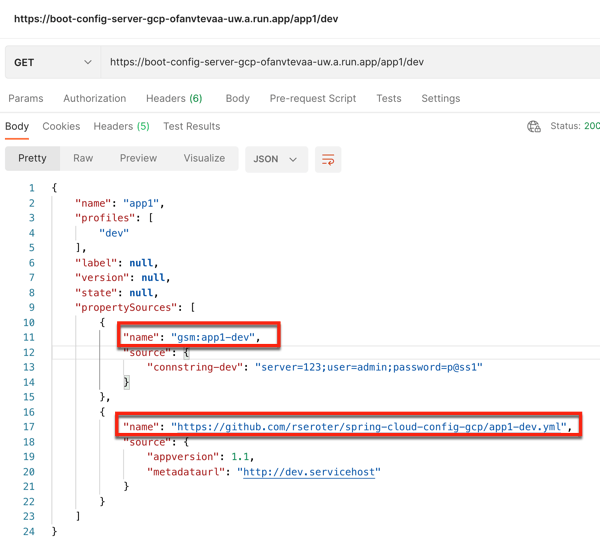

But there’s more. Cloud Run does apps too. That means instead of a few standalone functions to serve a rich REST endpoint, you’re deploying one Spring Boot app with all the requisite listeners. Instead of serving out a static site, you could return a full web app with server-side capabilities. You’ve got nearly endless possibilities when you can serve any container that accepts HTTP, HTTP/2, WebSockets, or gRPC traffic.

Use either abstraction, but stay above the infrastructure and ship quickly.

| Docs: | Deploy container images, Deploy functions, Using gRPC, Invoke with an HTTPS request |

| Code labs to try: | Hello Cloud Run with Python, Getting Started with Cloud Run functions |

#2. You can run old AND new apps.

This is where the power of containers shows up, and why many previous attempts at PaaS didn’t break through. It’s ok if a platform only supports new architectures and new apps. But then you’re accepting that you’ll need an additional stack for EVERYTHING ELSE.

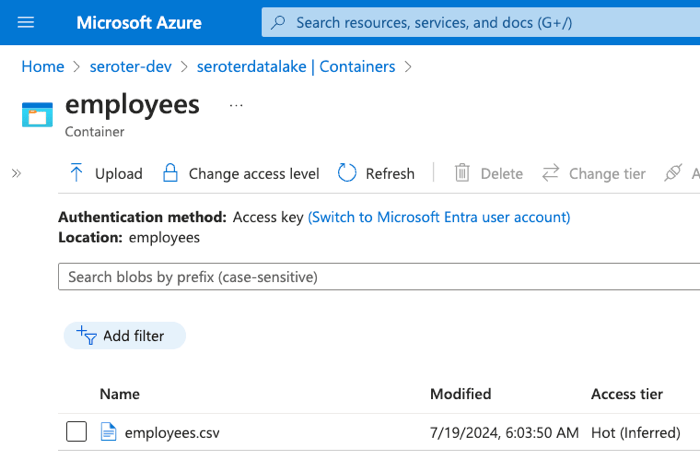

Cloud Run is a great choice because you don’t HAVE to start fresh to use it. Deploy from source in an existing GitHub repo or from cloned code on your machine. Maybe you’ve got an existing Next.js app sitting around that you want to deploy to Cloud Run. Run a headless CMS. Does your old app require local volume mounts for NFS file shares? Easy to do. Heck, I took a silly app I built 4 1/2 years ago, deployed it from the Docker Hub, and it just worked.

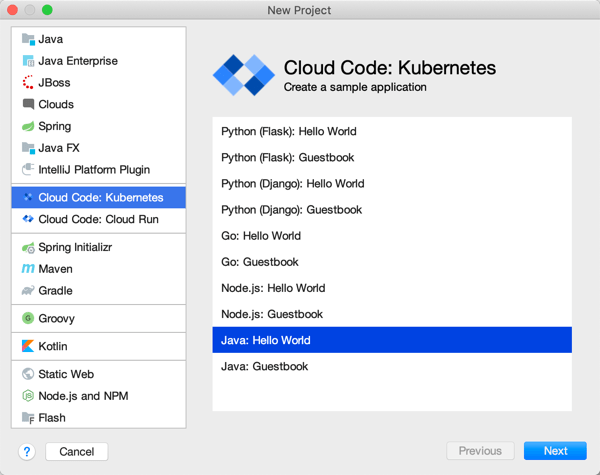

Of course, Cloud Run shines when you’re building new apps. Especially when you want fast experimentation with new paradigms. With its new GPU support, Cloud Run lets you do things like serve LLMs via tools like Ollama. Or deploy generative AI apps based on LangChain or Firebase Genkit. Build powerful web apps in Go, Java, Python, .NET, and more. Cloud Run’s clean developer experience and simple workflow makes it ideal for whatever you’re building next.

#3. Use by itself AND as part of a full cloud solution.

There aren’t many tech products that everyone seems to like. But folks seem to really like Cloud Run, and it regularly wins over the Hacker News crowd! Some classic PaaS solutions were lifestyle choices; you had to be all in. Use the platform and its whole way of working. Powerful, but limiting.

You can choose to use Cloud Run all by itself. It’s got a generous free tier, doesn’t require complicated HTTP gateways or routers to configure, and won’t force you to use a bunch of other Google Cloud services. Call out to databases hosted elsewhere, respond to webhooks from SaaS platforms, or just serve up static sites. Use Cloud Run, and Cloud Run alone, and be happy.

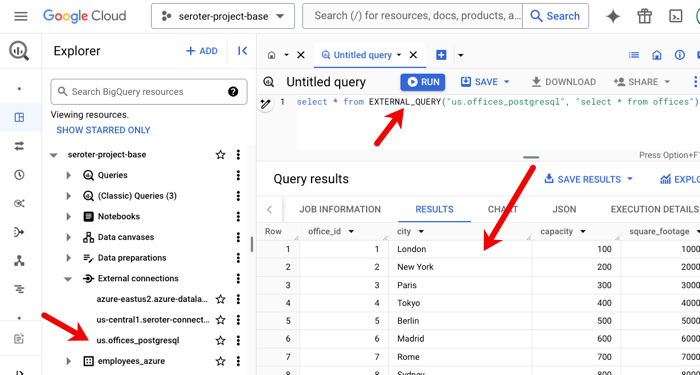

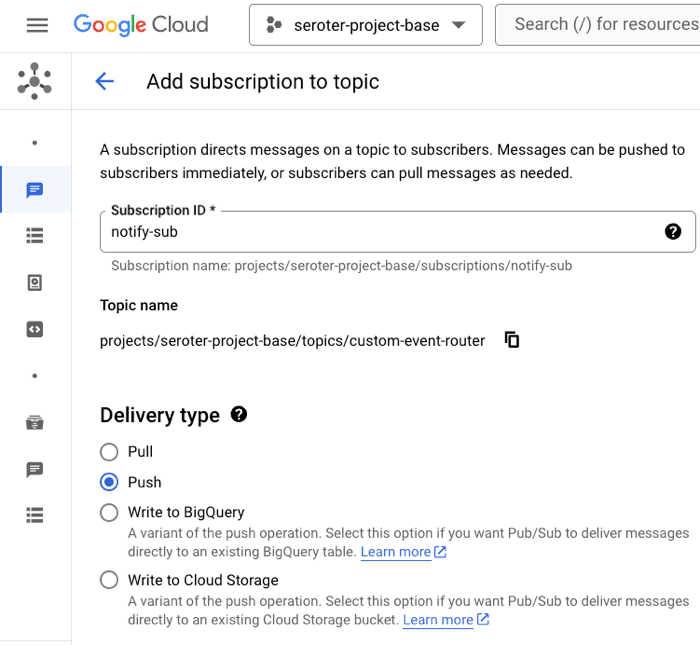

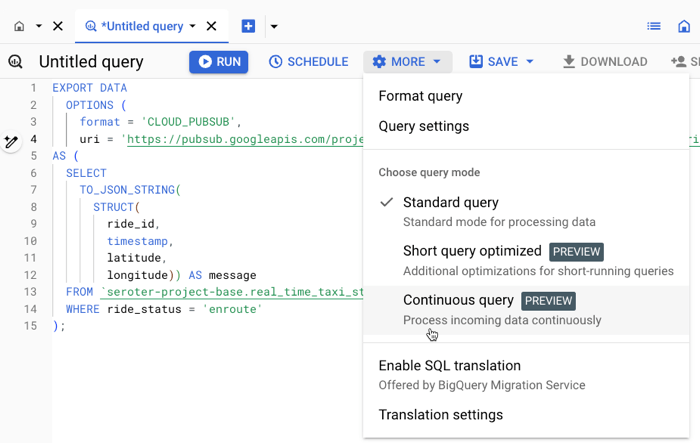

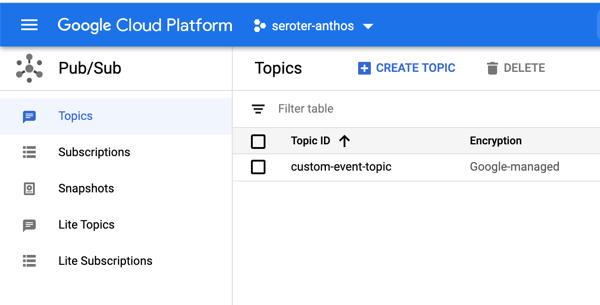

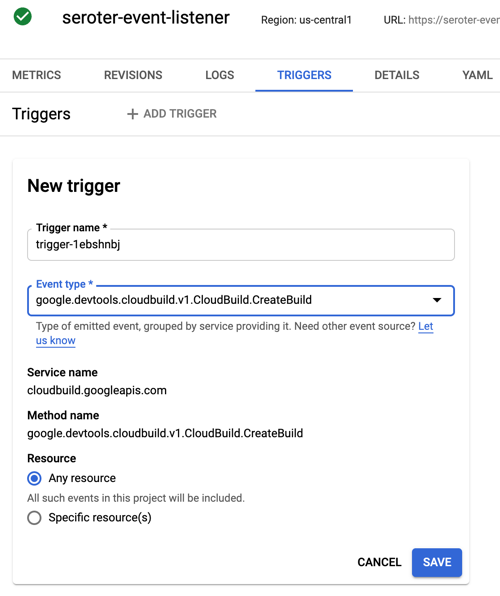

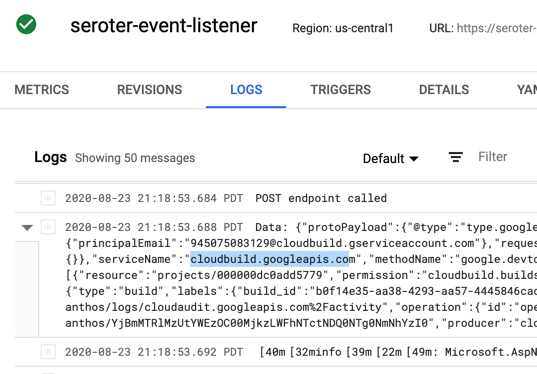

And of course, you can use it along with other great cloud services. Tack on a Firestore database for a flexible storage option. Add a Memorystore caching layer. Take advantage of our global load balancer. Call models hosted in Vertex AI. If you’re using Cloud Run as part of an event-driven architecture, you might also use built-in connections to Eventarc to trigger Cloud Run services when interesting things happen in your account—think file uploaded to object storage, user role deleted, database backup completes.

Use it by itself or “with the cloud”, but either way, there’s value.

#4. Choose simple AND sophisticated configurations.

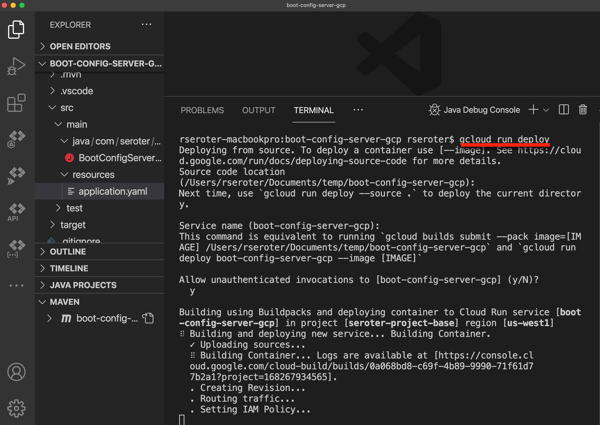

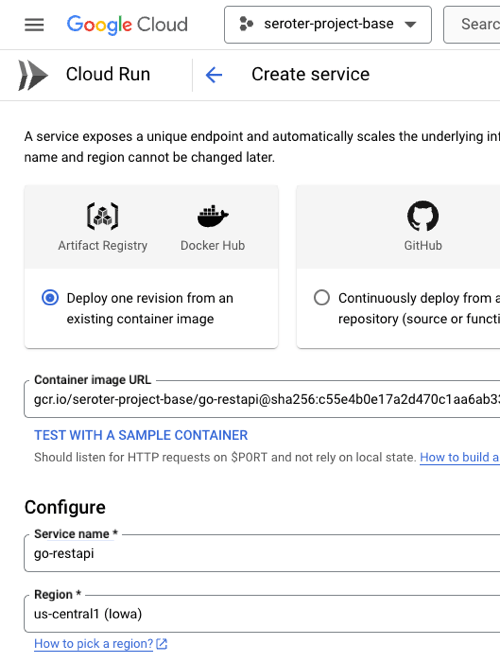

One reason PaaS-like services are so beloved is because they often provide a simple onramp without requiring tons of configuration. “cf push” to get an app to Cloud Foundry. Easy! Getting an app to Cloud Run is simple too. If you have a container, it’s a single command:

rseroter$ gcloud run deploy go-app --image=gcr.io/seroter-project-base/go-restapi

If all you have is source code, it’s also a single command:

rseroter$ gcloud run deploy node-app --source .

In both cases, the CLI asks me to pick a region and whether I want requests authenticated, and that’s it. Seconds later, my app is running.

This works because Cloud Run sets a series of smart, reasonable default settings.

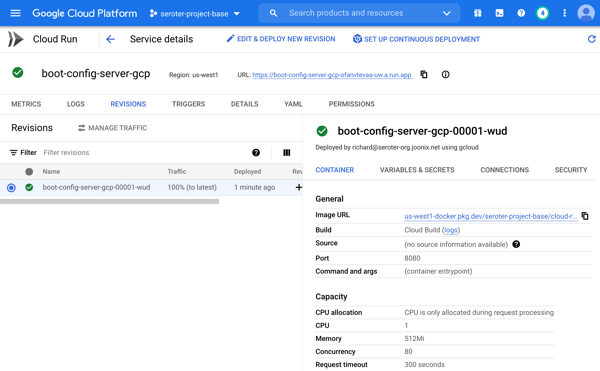

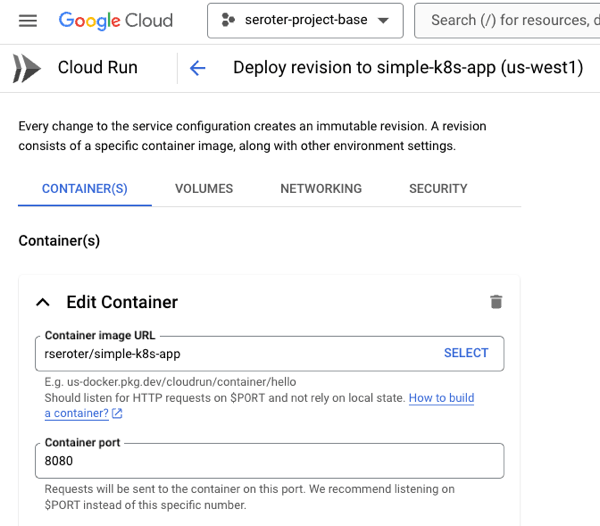

But sometimes you do want more control over service configuration, and Cloud Run opens up dozens of possible settings. What kind of sophisticated settings do you have control over?

- CPU allocation. Do you want CPU to be always on, or quit when idle?

- Ingress controls. Do you want VPC-only access or public access?

- Multi-container services. Add a sidecar.

- Container port. The default is 8080, but set to whatever you want.

- Memory. The default value is 512 MiB per instance, but you can go up to 32GB.

- CPU. It defaults to 1, but you can go less than 1, or up to 8.

- Healthchecks. Define startup or liveliness checks that ping specific endpoints on a schedule.

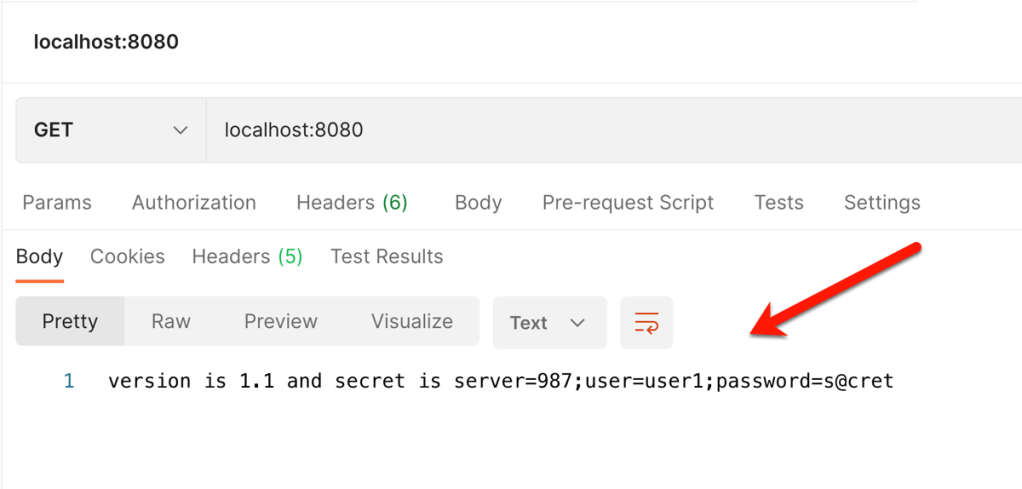

- Variables and secrets. Define environment variables that get injected at runtime. Same with secrets that get mounted at runtime.

- Persistent storage volumes. There’s ephemeral scratch storage in every Cloud Run instance, but you can also mount volumes from Cloud Storage buckets or NFS shares.

- Request timeout. The default value is 5 minutes, but you can go up to 60 minutes.

- Max concurrency. A given service instance can handle more than one request. The default value is 80, but you can go up to 1000!

- and much more!

You can do something simple, you can do something sophisticated, or a bit of both.

#5. Create public AND private services.

One of the challenge with early PaaS services was that they were just sitting on the public internet. That’s no good as you get to serious, internal-facing systems.

First off, Cloud Run services are public by default. You control the authentication level (anonymous access, or authenticated user) and need to explicitly set that. But the service itself is publicly reachable. What’s great is that this doesn’t require you to set up any weird gateways or load balancers to make it work. As soon as you deploy a service, you get a reachable address.

Awesome! Very easy. But what if you want to lock things down? This isn’t difficult either.

Cloud Run lets me specify that I’ll only accept traffic from my VPC networks. I can also choose to securely send messages to IPs within a VPC. This comes into play as well if you’re routing requests to a private on-premises network peered with a cloud VPC. We even just added support for adding Cloud Run services to a service mesh for more networking flexibility. All of this gives you a lot of control to create truly private services.

#6. Scale to zero AND scale to 1.

I don’t necessarily believe that cloud is more expensive than on-premises—regardless of some well-publicized stories—but keeping idle cloud services running isn’t helping your cost posture.

Google Cloud Run truly scales to zero. If nothing is happening, nothing is running (or costing you anything). However, when you need to scale, Cloud Run scales quickly. Like, a-thousand-instances-in-seconds quickly. This is great for bursty workloads that don’t have a consistent usage pattern.

But you probably want the option to have an affordable way to keep a consistent pool of compute online to handle a steady stream of requests. No problem. Set the minimum instance to 1 (or 2, or 10) and keep instances warm. And, set concurrency high for apps that can handle it.

If you don’t have CPU always allocated, but keep a minimum instance online, we actually charge you significantly less for that “warm” instance. And you can apply committed use discounts when you know you’ll have a service running for a while.

Run bursty workloads or steadily-used workloads all in a single platform.

| Docs: | About instance autoscaling in Cloud Run services, Set minimum instances, Load testing best practices |

| Code labs to try: | Cloud Run service with minimum instances |

#7. Do one-off deploys AND set up continuous delivery pipelines.

I mentioned above that it’s easy to use a single command or single screen to get an app to Cloud Run. Go from source code or container to running app in seconds. And you don’t have to set up any other routing middleware or Cloud networking to get a routable serivce.

Sometimes you just want to do a one-off deploy without all the ceremony. Run the CLI, use the Console UI, and get on with life. Amazing.

But if that was your only option, you’d feel constrained. So you can use something like GitHub Actions to deploy to Cloud Run. Most major CI/CD products support it.

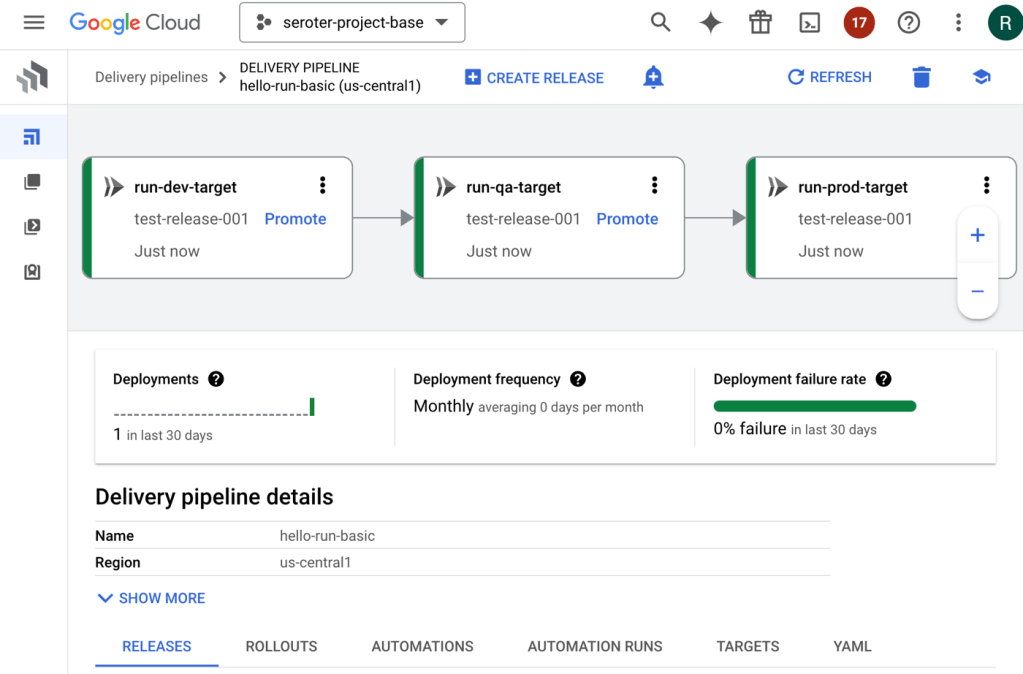

Another great option is Google Cloud Deploy. This managed service takes container artifacts and deploys them to Google Kubernetes Engine or Google Cloud Run. It offers some sophisticated controls for canary deploys, parallel deploys, post-deploy hooks, and more.

Cloud Deploy has built-in support for Cloud Run. A basic pipeline (defined in YAML, but also configured via point-and-click in the UI if you want) might show three stages for dev, test, and prod.

When the pipeline completes, we see three separate Cloud Run instances deployed, representing each stage of the pipeline.

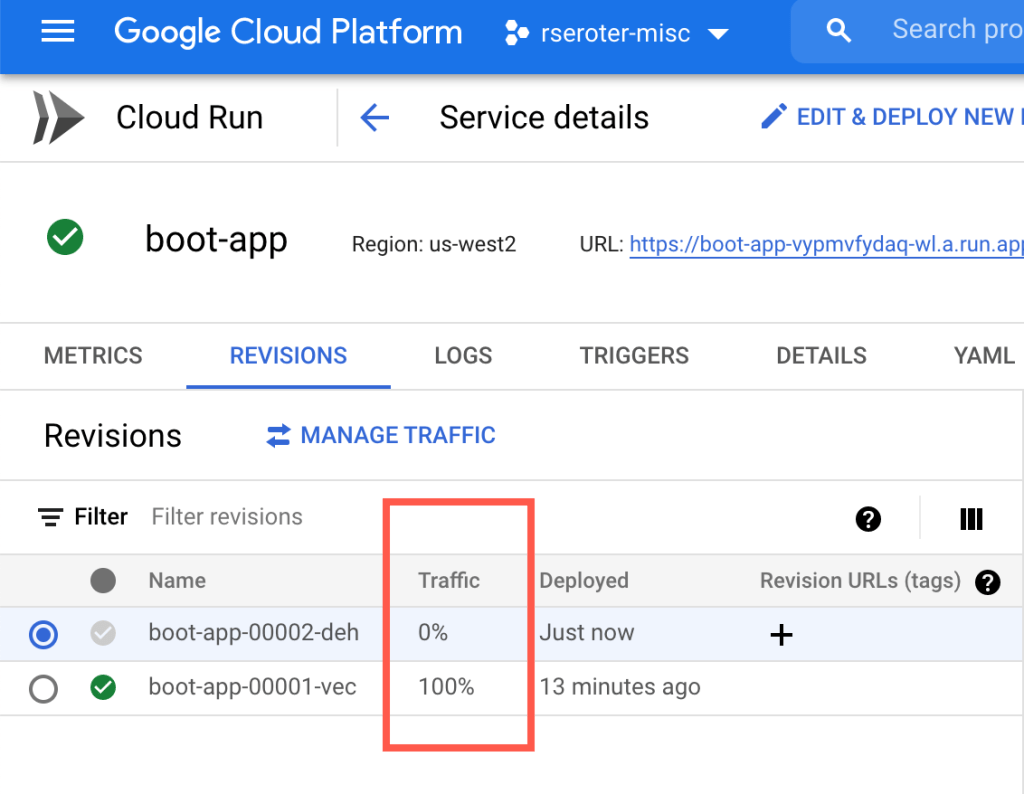

You want something more sophisticated? Ok. Cloud Deploy supports Cloud Run canary deployments. You’d use this if you want a subset of traffic to go to the new instance before deciding to cut over fully.

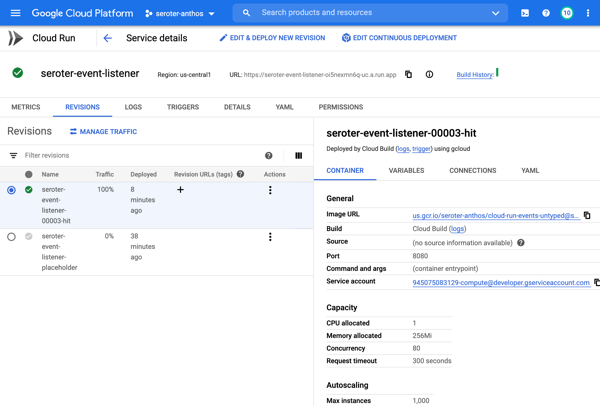

This is taking advantage of Cloud Run’s built-in traffic management feature. When I check the deployed service, I see that after advancing my pipeline to 75% of production traffic for the new app version, the traffic settings are properly set in Cloud Run.

Serving traffic in multiple regions? Cloud Deploy makes it possible to ship a release to dozens of places simultaneously. Here’s a multi-target pipeline. The production stage deploys to multiple Cloud Run regions in the US.

When I checked Cloud Run, I saw instances in all the target regions. Very cool!

If you want a simple deploy, do that with the CLI or UI. Nothing stops you. However, if you’re aiming for a more robust deployment strategy, Cloud Run readily handles it through services like Cloud Deploy.

#8. Own aspects of security AND offload responsibility.

On reason that you choose managed compute platforms is to outsource operational tasks. It doesn’t mean you’re not capable of patching infrastructure, scaling compute nodes, or securing workloads. It means you don’t want to, and there are better uses of your time.

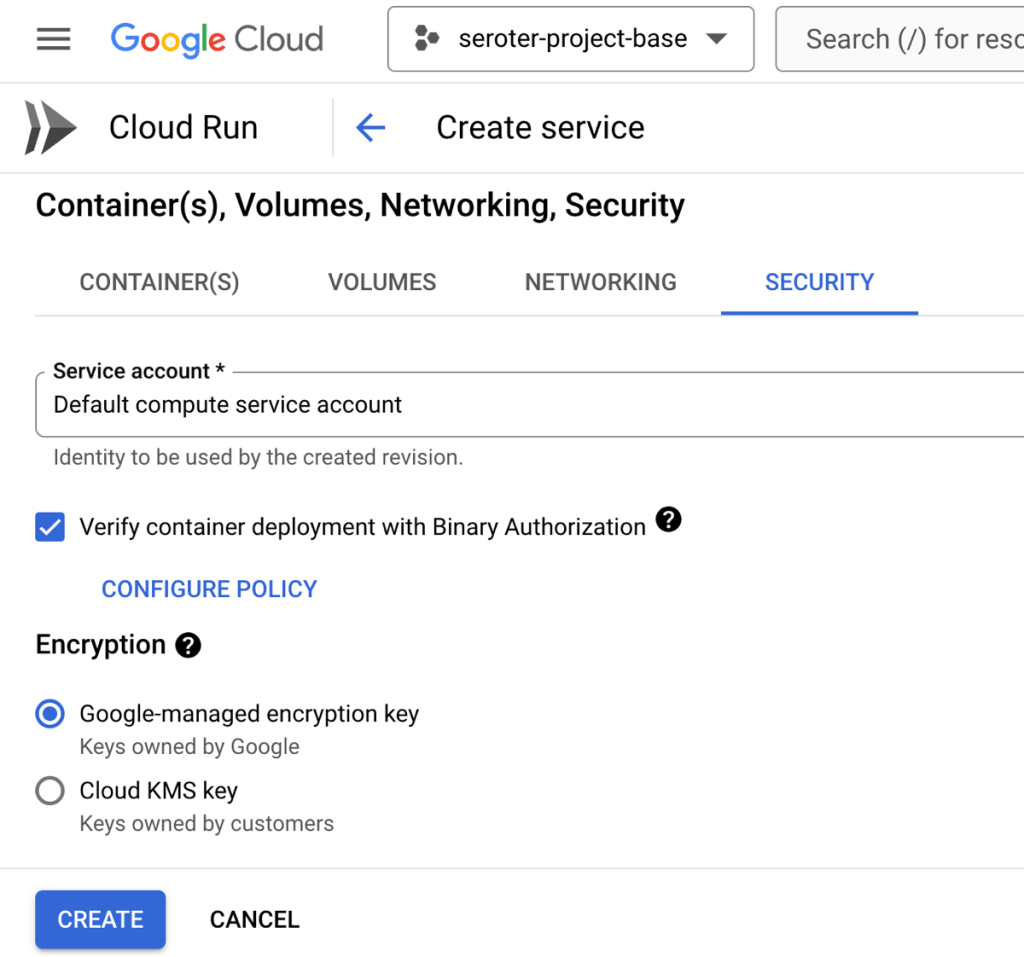

With Cloud Run, you can drive aspects of your security posture, and also let Cloud Run handle key aspects on your behalf.

What are you responsible for? You choose an authentication approach, including public or private services. This includes control of how you want to authenticate developers who use Cloud Run. You can authenticate end users, internal or external ones, using a handful of supported methods.

It’s also up to you to decide which service account the Cloud Service instance should impersonate. This controls what a given instance has access to. If you want to ensure that only containers with verified provenance get deployed, you can also choose to turn on Binary Authorization.

So what are you offloading to Cloud Run and Google Cloud?

You can outsource protection from DDoS and other threats by turning on Cloud Armor. The underlying infrastructure beneath Cloud Run is completely managed, so you don’t need to worry about upgrading or patching any of that. What’s also awesome is that if you deploy Cloud Run services from source, you can sign up for automatic base image updates. This means we’ll patch the OS and runtime of your containers. Importantly, it’s still up to you to patch your app dependencies. But this is still very valuable!

#9. Treat as post-build target AND as upfront platform choice.

You might just want a compute host for your finished app. You don’t want to have to pick that host up front, and just want a way to run your app. Fair enough! There aren’t “Cloud Run apps”; they’re just containers. That said, there are general tips that make an app more suitable for Cloud Run than not. But the key is, for modern apps, you can often choose to treat Cloud Run as a post-build decision.

Or, you can design with Cloud Run in mind. Maybe you want to trigger Cloud Run based on a specific Eventarc event. Or you want to capitalize on Cloud Run concurrency so you code accordingly. You could choose to build based on a specific integration provided by Cloud Run (e.g. Memorystore, Firestore, or Firebase Hosting).

There are times that you build with the target platform in mind. In other cases, you want a general purpose host. Cloud Run is suitable for either situation, which makes it feel unique to me.

| Docs: | Optimize Java applications for Cloud Run, Integrate with Google Cloud products in Cloud Run, Trigger with events |

| Code labs to try: | Trigger Cloud Run with Eventarc events |

#10. Rely on built-in SLOs, logs, metrics AND use your own observability tools.

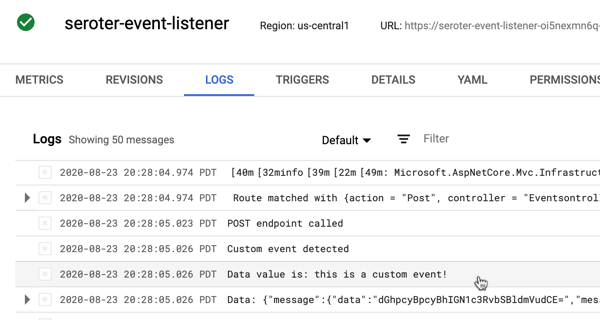

If you want it to be, Cloud Run can feel like an all-in-one solution. Do everything from one place. That’s how classic PaaS was, and there was value in having a tightly-integrated experience. From within Cloud Run, you have built-in access to logs, metrics, and even setting up SLOs.

The metrics experience is powered by Cloud Monitoring. I can customize event types, the dashboards, time window, and more. This even includes the ability to set uptime checks which periodically ping your service and let you know if everything is ok.

The embedded logging experience is powered by Cloud Logging and gives you a view into all your system and custom logs.

We’ve even added an SLO capability where you can define SLIs based on availability, latency, or custom metrics. Then you set up service level objectives for service performance.

While all these integrations are terrific, you don’t have to only use this. You can feed metrics and logs into Datadog. Same with Dynatrace. You can also write out OpenTelemetry metrics or Prometheus metrics and consume those how you want.

| Docs: | Monitor Health and Performance, Logging and viewing logs in Cloud Run, Using distributed tracing |

Kubernetes, virtual machines, and bare metal boxes all play a key role for many workloads. But you also may want to start with the highest abstraction possible so that you can focus on apps, not infrastructure. IMHO, Google Cloud Run is the best around and satisfies the needs of most any modern web app. Give it a try!