Be still and wait. This was the best advice I heard in 2019, and it took until the end of the year for me to realize it. Usually, when I itch for a change, I go all in, right away. I’m prone to thinking that “patience” is really just “indecision.” It’s not. The best things that happened this year were the things that didn’t happen when I wanted! I’m grateful for an eventful, productive, and joyful year where every situation worked out for the best.

2019 was something else. My family grew, we upgraded homes, my team was amazing, my company was acquired by VMware, I spoke at a few events around the world, chaired a tech conference, kept up a podcast, created a couple new Pluralsight classes, continued writing for InfoQ.com, and was awarded a Microsoft MVP for the 12th straight time.

For the last decade+, I’ve started each year by recapping the last one. I usually look back at things I wrote, and books I read. This year, I’ll also add “things I watched.”

Things I Watched

I don’t want a ton of “regular” TV—although I am addicted to Bob’s Burgers and really like the new FBI—and found myself streaming or downloading more things while traveling this year. These shows/seasons stood out to me:

Crashing – Season 3 [HBO] Pete Holmes is one of my favorite stand-up comedians, and this show has some legit funny moments, but it’s also complex, dark, and real. This was a good season with a great ending.

BoJack Horseman – Season 5 [Netflix] Again, a show with absurdist humor, but also a dark, sobering streak. I’m got to catch up on the latest season, but this one was solid.

Orange is the New Black – Season 7 [Netflix] This show has had some ups and downs, but I’ve stuck with it because I really like the cast, and there are enough surprises to keep me hooked. This final season of the show was intense and satisfying.

Bosch – Season 4 [Amazon Prime] Probably the best thing I watched this year? I love this show. I’ve read all the books the show is based on, but the actors and writers have given this its own tone. This was a super tense season, and I couldn’t stop watching.

Schitt’s Creek – Seasons 1-4 [Netflix] Tremendous cast and my favorite overall show from 2019. Great writing, and some of the best characters on TV. Highly recommended.

Jack Ryan – Season 1 [Amazon Prime] Wow, what a show. Throughly enjoyed the story and cast. Plenty of twists and turns that led me to binge watch this on one of my trips this year.

Things I Wrote

I kept up a reasonable writing rhythm on my own blog, as well as publication to the Pivotal blog and InfoQ.com site. Here were a few pieces I enjoyed writing the most:

[Pivotal blog] Five part series on digital transformation. You know what you should never do? Write a blog post and in it, promise that you’ll write four more. SO MUCH PRESSURE. After the overview post, I looked at the paradox of choice, design thinking, data processing, and automated delivery. I’m proud of how it all ended up.

[blog] Which of the 295,680 platform combinations will you create on Microsoft Azure? The point of this post wasn’t that Microsoft, or any cloud provider for that matter, has a lot of unique services. They do, but the point was that we are prone to thinking that we’re getting a complete solution from someone, but really getting some really cool components to stitch together.

[Pivotal blog] Kubernetes is a platform for building platforms. Here’s what that means. This is probably my favorite piece I wrote this year. It required a healthy amount of research and peer review, and dug into something I see very few people talking about.

[blog] Go “multi-cloud” while *still* using unique cloud services? I did it using Spring Boot and MongoDB APIs. There’s so many strawman arguments on Twitter when it comes to multi-cloud that it’s like a scarecrow convention. Most people I see using multiple clouds aren’t dumb or lazy. They have real reasons, including a well-founded lack of trust in putting all their tech in one vendor’s basket. This blog post looked at how to get the best of all worlds.

[blog] Looking to continuously test and patch container images? I’ll show you one way. I’m not sure when I give up on being a hands on technology person. Maybe never? This was a demo I put together for my VMworld Barcelona talk, and like the final result.

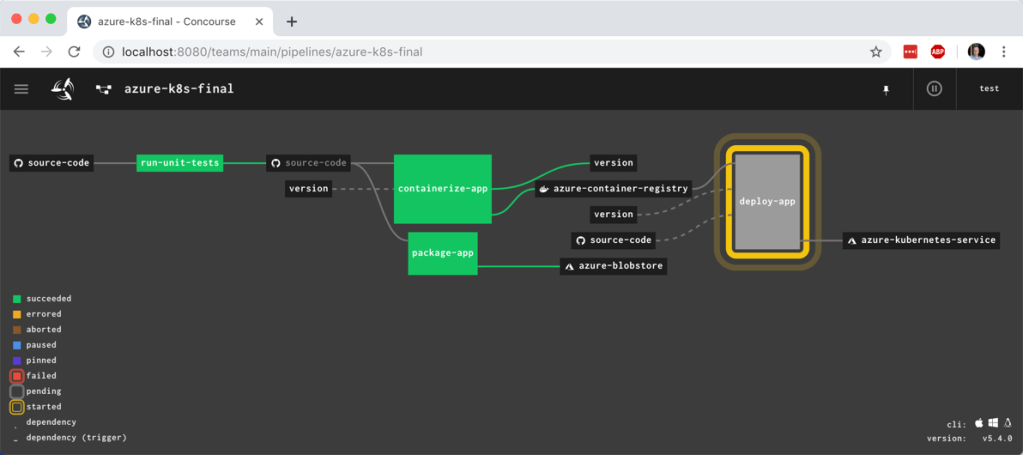

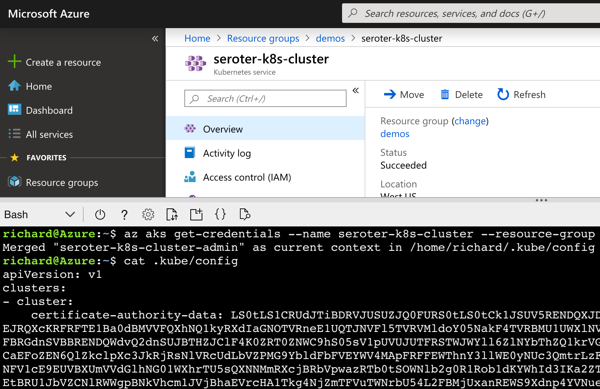

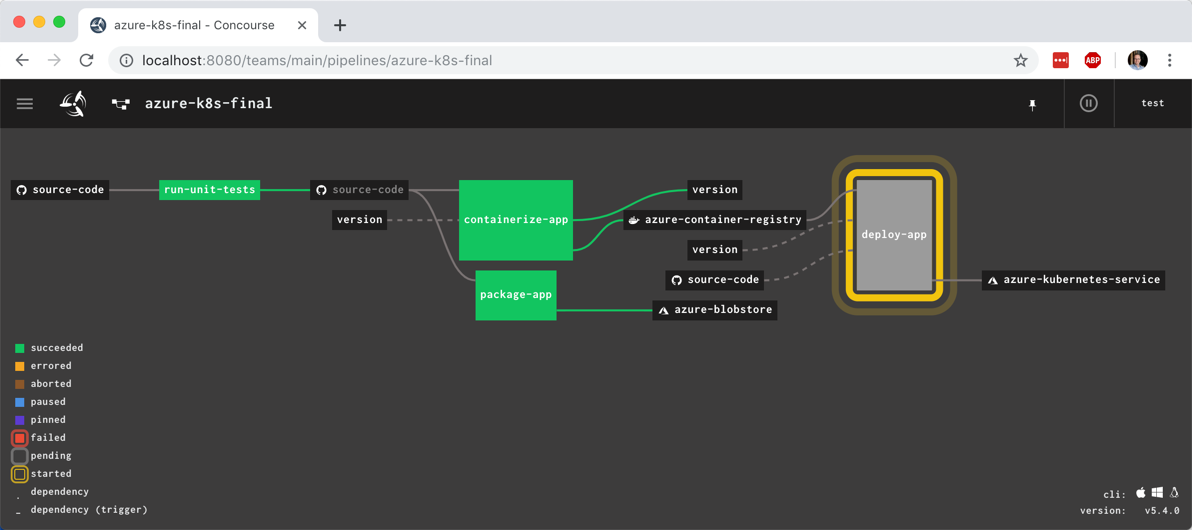

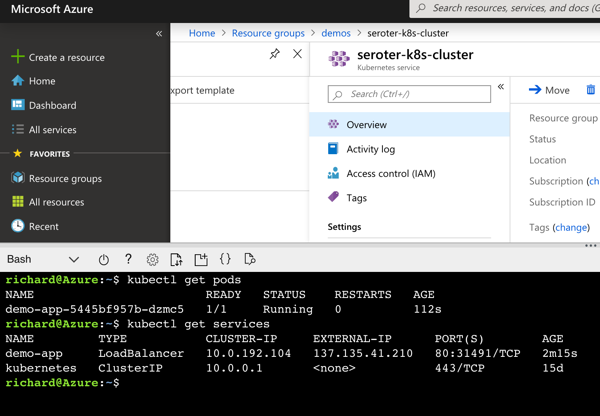

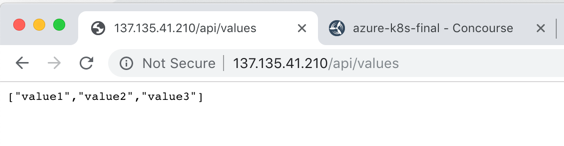

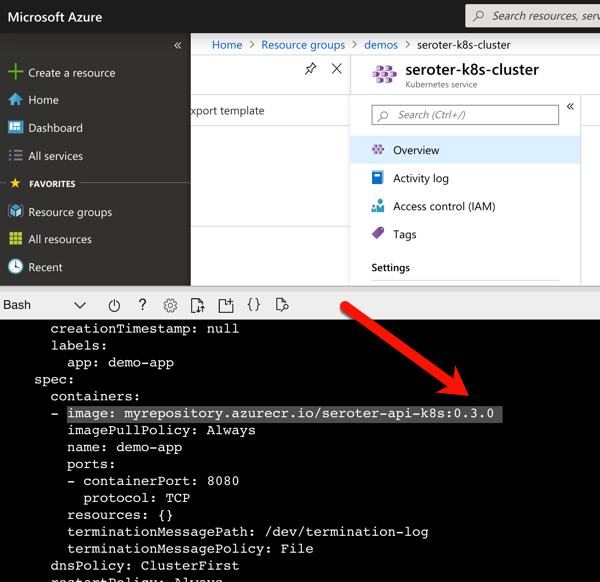

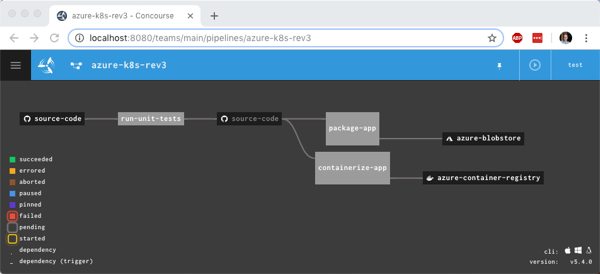

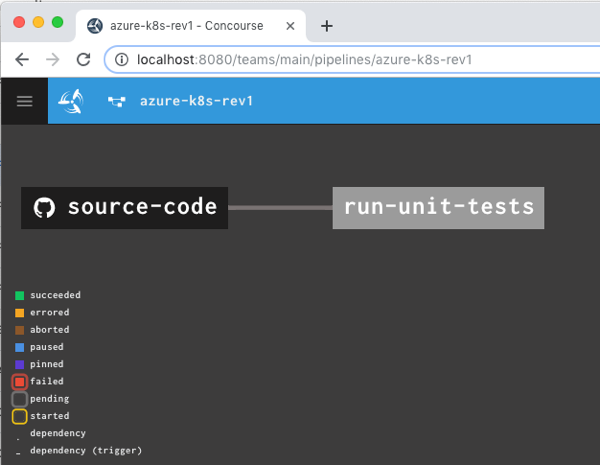

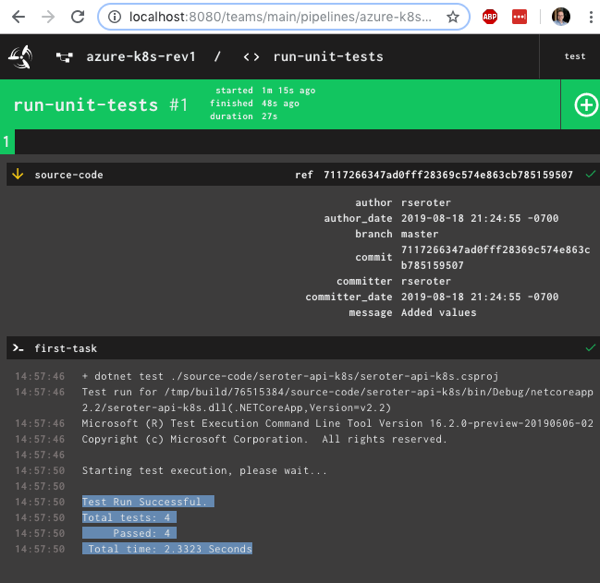

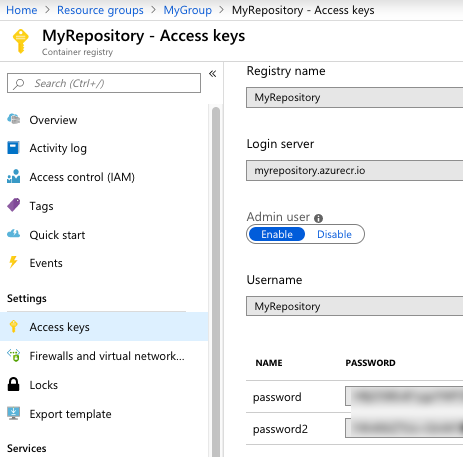

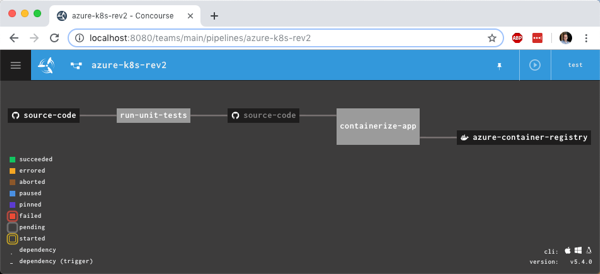

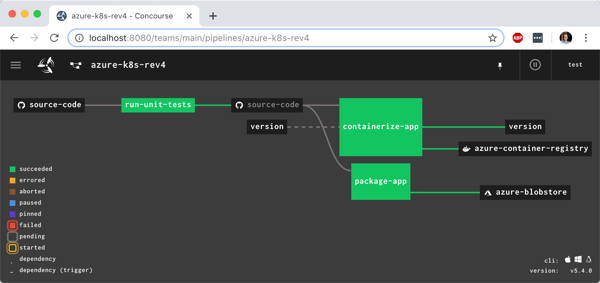

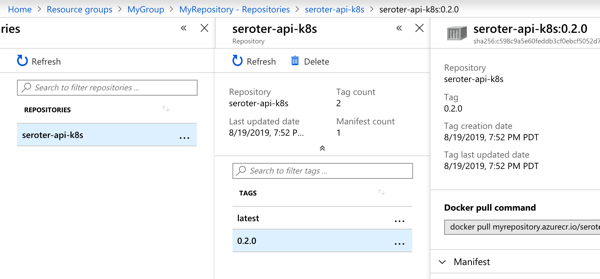

[blog] Building an Azure-powered Concourse pipeline for Kubernetes – Part 3: Deploying containers to Kubernetes. I waved the white flag and learned Kubernetes this year. One way I forced myself to do so was sign up to teach an all-day class with my friend Rocky. While leading up to that, I wrote up this 3-part series of posts on continuous delivery of containers.

[blog] Want to yank configuration values from your .NET Core apps? Here’s how to store and access them in Azure and AWS. It’s fun to play with brand new tech, curse at it, and document your journey for others so they curse less. Here I tried out Microsoft’s new configuration storage service, and compared it to other options.

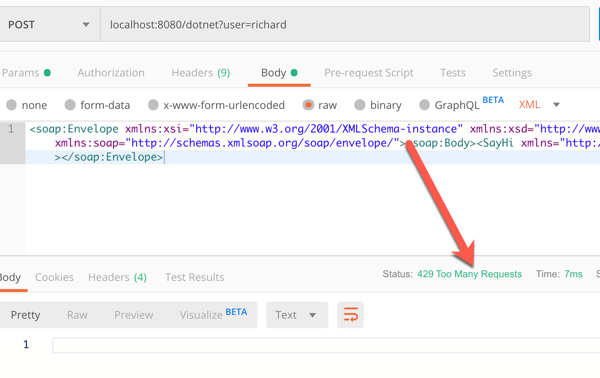

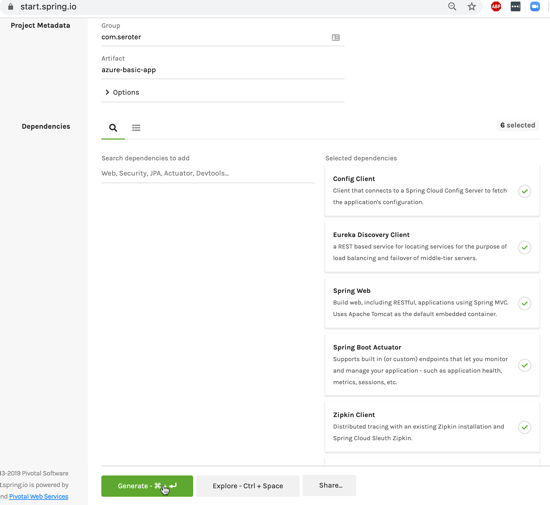

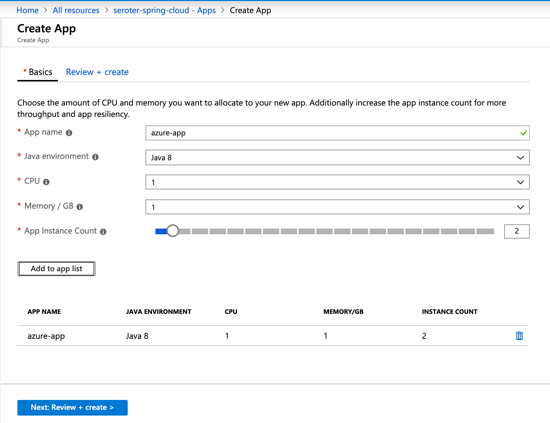

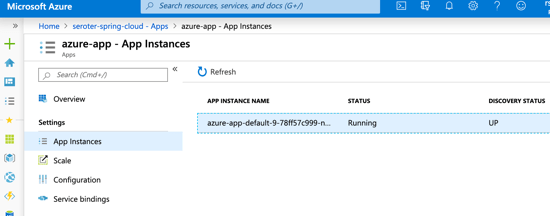

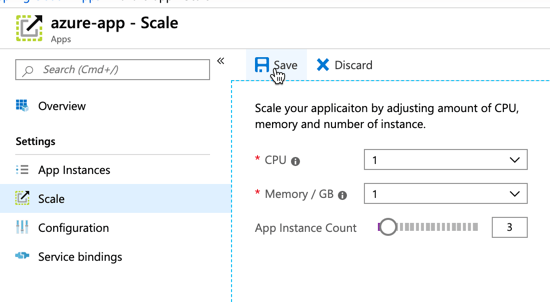

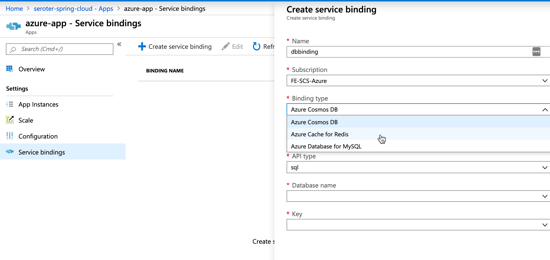

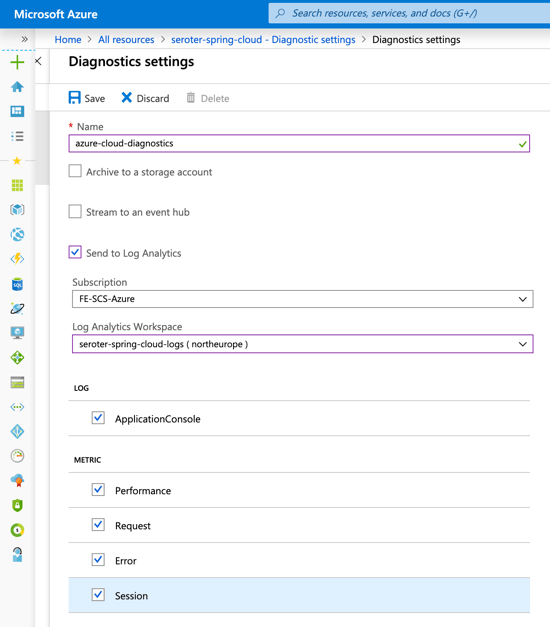

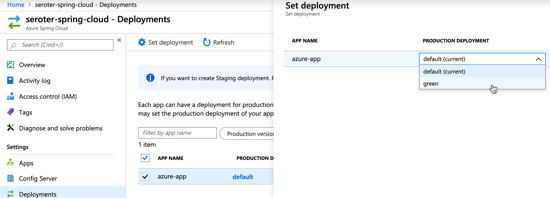

[blog] First Look: Building Java microservices with the new Azure Spring Cloud. Sometimes it’s fun to be first. Pivotal worked with Microsoft on this offering, so on the day it was announced, I had a blog post ready to go. Keep an eye on this service in 2020; I think it’ll be big.

[InfoQ] Swim Open Sources Platform That Challenges Conventional Wisdom in Distributed Computing. One reason I keep writing for InfoQ is that it helps me discover exciting new things. I don’t know if SWIM will be a thing long term, but their integrated story is unconventional in today’s “I’ll build it all myself” world.

[InfoQ] Weaveworks Releases Ignite, AWS Firecracker-Powered Software for Running Containers as VMs. The other reason I keep writing for InfoQ is that I get to talk to interesting people and learn from them. Here, I engaged in an informative Q&A with Alexis and pulled out some useful tidbits about GitOps.

[InfoQ] Cloudflare Releases Workers KV, a Serverless Key-Value Store at the Edge. Feels like edge computing has the potential to disrupt our current thinking about what a “cloud” is. I kept an eye on Cloudflare this year, and this edge database warranted a closer look.

Things I Read

I like to try and read a few books a month, but my pace was tested this year. Mainly because I chose to read a handful of enormous biographies that took a while to get through. I REGRET NOTHING. Among the 32 books I ended up finishing in 2019, these were my favorites:

Churchill: Walking with Destiny by Andrew Roberts (@aroberts_andrew). This was the most “highlighted” book on my Kindle this year. I knew the caricature, but not the man himself. This was a remarkably detailed and insightful look into one of the giants of the 20th century, and maybe all of history. He made plenty of mistakes, and plenty of brilliant decisions. His prolific writing and painting were news to me. He’s a lesson in productivity.

At Home: A Short History of Private Life by Bill Bryson. This could be my favorite read of 2019. Bryson walks around his old home, and tells the story of how each room played a part in the evolution of private life. It’s a fun, fascinating look at the history of kitchens, studies, bedrooms, living rooms, and more. I promise that after you read this book, you’ll be more interesting at parties.

Messengers: Who We Listen To, Who We Don’t, and Why by Stephen Martin (@scienceofyes) and Joseph Marks (@Joemarks13). Why is it that good ideas get ignored and bad ideas embraced? Sometimes it depends on who the messenger is. I enjoyed this book that looked at eight traits that reliably predict if you’ll listen to the messenger: status, competence, attractiveness, dominance, warm, vulnerability, trustworthiness, and charisma.

Six Days of War: June 1967 and the Making of the Modern Middle East by Michael Oren (@DrMichaelOren). What a story. I had only a fuzzy understanding of what led us to the Middle East we know today. This was a well-written, engaging book about one of the most consequential events of the 20th century.

The Unicorn Project: A Novel about Developers, Digital Disruption, and Thriving in the Age of Data by Gene Kim (@RealGeneKim). The Phoenix Project is a must-read for anyone trying to modernize IT. Gene wrote that book from a top-down leadership perspective. In The Unicorn Project, he looks at the same situation, but from the bottom-up perspective. While written in novel form, the book is full of actionable advice on how to chip away at the decades of bureaucratic cruft that demoralizes IT and prevents forward progress.

Talk Triggers: The Complete Guide to Creating Customers with Word of Mouth by Jay Baer (@jaybaer) and Daniel Lemin (@daniellemin). Does your business have a “talk trigger” that leads customers to voluntarily tell your story to others? I liked the ideas put forth by the authors, and the challenge to break out from the pack with an approach (NOT a marketing gimmick) that really resonates with customers.

I Heart Logs: Event Data, Stream Processing, and Data Integration by Jay Kreps (@jaykreps). It can seem like Apache Kafka is the answer to everything nowadays. But go back to the beginning and read Jay’s great book on the value of the humble log. And how it facilitates continuous data processing in ways that preceding technologies struggled with.

Kafka: The Definitive Guide: Real-Time Data and Stream Processing at Scale by Neha Narkhede (@nehanarkhede), Gwen Shapira (@gwenshap), and Todd Palino (@bonkoif). Apache Kafka is probably one of the five most impactful OSS projects of the last ten years, and you’d benefit from reading this book by the people who know it. Check it out for a great deep dive into how it works, how to use it, and how to operate it.

The Players Ball: A Genius, a Con Man, and the Secret History of the Internet’s Rise by David Kushner (@davidkushner). Terrific story that you’ve probably never heard before, but have felt its impact. It’s a wild tale of the early days of the Web where the owner of sex.com—who also created match.com—had it stolen, and fought to get it back. It’s hard to believe this is a true story.

Mortal Prey by John Sanford. I’ve read a dozen+ of the books in this series, and keep coming back for more. I’m a sucker for a crime story, and this is a great one. Good characters, well-paced plots.

Your God is Too Safe: Rediscovering the Wonder of a God You Can’t Control by Mark Buchanan (@markaldham). A powerful challenge that I needed to hear last year. You can extrapolate the main point to many domains—is something you embrace (spirituality, social cause, etc) a hobby, or a belief? Is it something convenient to have when you want it, or something powerful you do without regard for the consequences? We should push ourselves to get off the fence!

Escaping the Build Trap: How Effective Product Management Creates Real Value by Melissa Perri (@lissijean). I’m not a product manager any longer, but I still care deeply about building the right things. Melissa’s book is a must-read for people in any role, as the “build trap” (success measured by output instead of outcomes) infects an entire organization, not just those directly developing products. It’s not an easy change to make, but this book offers tangible guidance to making the transition.

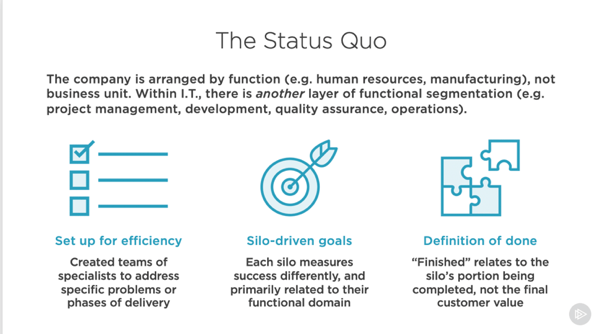

Project to Product: How to Survive and Thrive in the Age of Digital Disruption with the Flow Framework by Mik Kersten (@mik_kersten). This is such a valuable book for anyone trying to unleash their “stuck” I.T. organization. Mik does a terrific job explaining what’s not working given today’s realities, and how to unify an organization around the value streams that matter. The “flow framework” that he pioneered, and explains here, is a brilliant way of visualizing and tracking meaningful work.

Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World by David Epstein (@DavidEpstein). I felt “seen” when I read this. Admittedly, I’ve always felt like an oddball who wasn’t exceptional at one thing, but pretty good at a number of things. This book makes the case that breadth is great, and most of today’s challenges demand knowledge transfer between disciplines and big-picture perspective. If you’re a parent, read this to avoid over-specializing your child at the cost of their broader development. And if you’re starting or midway through a career, read this for inspiration on what to do next.

John Newton: From Disgrace to Amazing Grace by Jonathan Aitken. Sure, everyone knows the song, but do you know the man? He had a remarkable life. He was the captain of a slave ship, later a pastor and prolific writer, and directly influenced the end of the slave trade.

Blue Ocean Shift: Beyond Competing – Proven Steps to Inspire Confidence and Seize New Growth by W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne. This is a book about surviving disruption, and thriving. It’s about breaking out of the red, bloody ocean of competition and finding a clear, blue ocean to dominate. I liked the guidance and techniques presented here. Great read.

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson (@WalterIsaacson). Huge biography, well worth the time commitment. Leonardo had range. Mostly self-taught, da Vinci studying a variety of topics, and preferred working through ideas to actually executing on them. That’s why he had so many unfinished projects! It’s amazing to think of his lasting impact on art, science, and engineering, and I was inspired by his insatiable curiosity.

AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order by Kai-Fu Lee (@kaifulee). Get past some of the hype on artificial intelligence, and read this grounded book on what’s happening RIGHT NOW. This book will make you much smarter on the history of AI research, and what AI even means. It also explains how China has a leg up on the rest of the world, and gives you practical scenarios where AI will have a big impact on our lives.

Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On It by Chris Voss (@VossNegotiation) and Tahl Raz (@tahlraz). I’m fascinated by the psychology of persuasion. Who better to learn negotiation from than an FBI’s international kidnapping negotiator? He promotes empathy over arguments, and while the book is full of tactics, it’s not about insincere manipulation. It’s about getting to a mutually beneficial state.

Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery by Eric Metaxas (@ericmetaxas). It’s tragic that this generation doesn’t know or appreciate Wilberforce. The author says that Wilberforce could be the “greatest social reformer in the history of the world.” Why? His decades-long campaign to abolish slavery from Europe took bravery, conviction, and effort you rarely see today. Terrific story, well written.

Unlearn: : Let Go of Past Success to Achieve Extraordinary Results by Barry O’Reilly (@barryoreilly). Barry says that “unlearning” is a system of letting go and adapting to the present state. He gives good examples, and offers actionable guidance for leaders and team members. This strikes me as a good book for a team to read together.

The Soul of a New Machine by Tracy Kidder. Our computer industry is younger than we tend to realize. This is such a great book on the early days, featuring Data General’s quest to design and build a new minicomputer. You can feel the pressure and tension this team was under. Many of the topics in the book—disruption, software compatibility, experimentation, software testing, hiring and retention—are still crazy relevant today.

Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World by Tom Wright (@TomWrightAsia) and Bradley Hope (@bradleyhope). Jho Low is a con man, but that sells him short. It’s hard not to admire his brazenness. He set up shell companies, siphoned money from government funds, and had access to more cash than almost any human alive. And he spent it. Low befriended celebrities and fooled auditors, until it all came crashing down just a few years ago.

Multipliers: How the Best Leaders Make Everyone Smarter by Liz Wiseman (@LizWiseman). It’s taken me very long (too long?) to appreciate that good managers don’t just get out of the way, they make me better. Wiseman challenges us to release the untapped potential of our organizations, and people. She contrasts the behavior of leaders that diminish their teams, and those that multiply their impact. Lots of food for thought here, and it made a direct impact on me this year.

Darwin’s Doubt: The Explosive Origin of Animal Life and the Case for Intelligent Design by Stephen Meyer (@StephenCMeyer). The vast majority of this fascinating, well-researched book is an exploration of the fossil record and a deep dive into Darwin’s theory, and how it holds up to the scientific research since then. Whether or not you agree with the conclusion that random mutation and natural selection alone can’t explain the diverse life that emerged on Earth over millions of years, it will give you a humbling appreciation for the biological fundamentals of life.

Napoleon: A Life by Adam Zamoyski. This was another monster biography that took me months to finish. Worth it. I had superficial knowledge of Napoleon. From humble beginnings, his ambition and talent took him to military celebrity, and eventually, the Emperorship. This meticulously researched book was an engaging read, and educational on the time period itself, not just Bonaparte’s rise and fall.

The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less by Barry Schwartz. I know I’ve used this term for year’s since it was part of other book’s I’ve read. But I wanted to go to the source. We hate having no choices, but are often paralyzed by having too many. This book explores the effects of choice on us, and why more is often less. It’s a valuable read, regardless of what job you have.

I say it every year, but thank you for having me as part of your universe in 2019. You do have a lot of choices of what to read or watch, and I truly appreciate when you take time to turn that attention to something of mine. Here’s to a great 2020!