At least 80% of the code I’ve ever written could have been written by AI, probably at higher quality. I’ve been “in tech” for twenty seven years and spent seven of those as a software developer. Even when I stopped getting paid for it, I never stopped coding. But little of it’s been truly novel; most of my code has been straightforward database access code, web APIs, presentation logic, and a handful of reasonably-complex systems. No doubt, many of you have done truly sophisticated things in code—compilers, performance-tuned algorithms, language frameworks—and AI isn’t replacing that any time soon. But I’d bet that much of the interesting tech work is moving away from raw code, and towards higher-order architecture.

I wanted to build out an agentic solution, and I used AI to generate 90% of the code. That code isn’t where the unique value was at. None of it was particularly noteworthy. You can find the whole app here. The most interesting work related to architectural decisions. Here are eight choices I had to make, and I suspect you’ll have fun wrestling with the same ones.

Choice #1 – What am I trying to accomplish and do agents make sense?

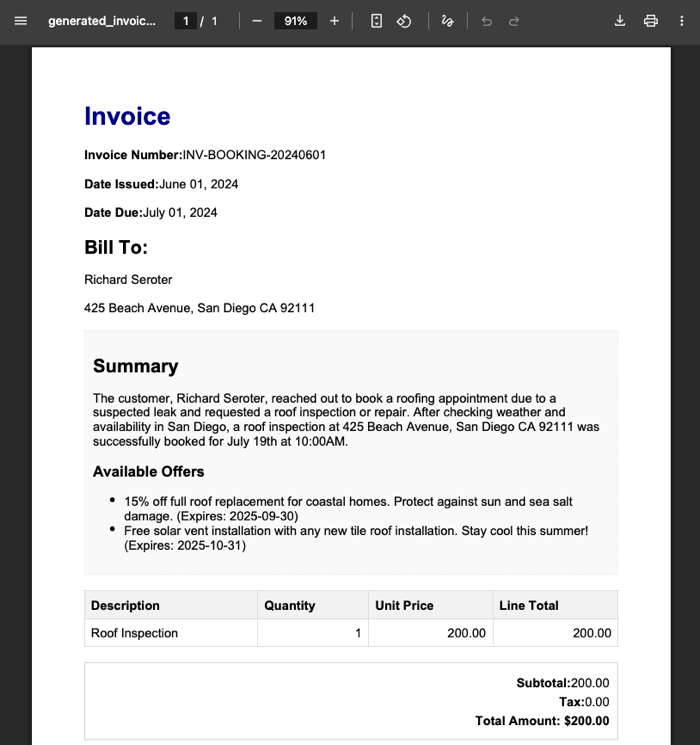

My goal was to build an app that could take in a customer’s roofing needs, create a service appointment, and generate a personalized invoice for the work. I’m cheating here, since this exercise started as “Richard wants to learn some agent tech.” So I did start with the end in mind. Judge me accordingly.

But in every legit situation, we start by evaluating the user need. What functional requirements do I need to satisfy? What performance or quality attributes are necessary? Can I solve this with a simple service, or modular monolith? Is the user flow deterministic or variable?

This scenario could certainly be solved by a simple data collection form and PDF generator. What requirements might make an agentic architecture the truly correct choice?

- Data collection from the user requires image, video, and audio input to best scope the services and pricing we should offer.

- The scheduling or invoicing process requires a dynamic workflow based on a variety of factors, and hard-coding all the conditions would be tricky.

Either way, this is always a critical choice before you write a single line of code.

Choice #2 – What data or services are available to work with?

Before we build anything new, what do we already have at our disposal?

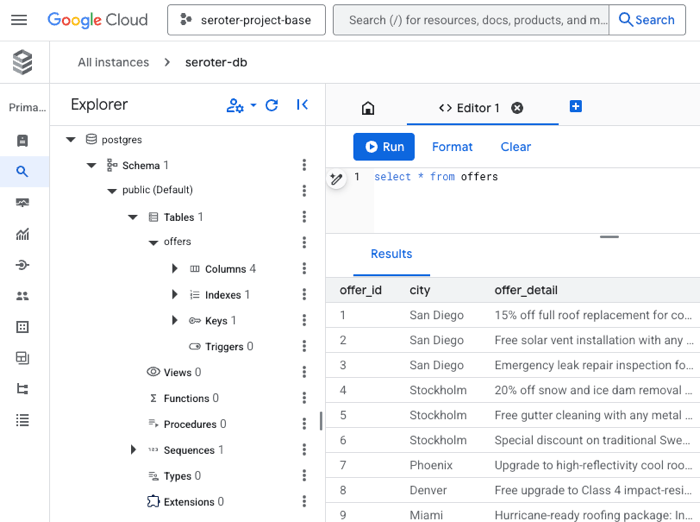

In my case, let’s assume I already have an appointments web API for retrieving available appointment times and making new appointments. I’ve also got an existing database that stores promotional offers that I want to conditionally add to my customer invoice. And I’ve got an existing Cloud Storage bucket where I store customer invoice PDFs.

It’s easy to just jump into the application build, but pause for a few moments and take stock of your existing inventory and what you can build around.

Choice #3 – What (agent) framework should I use and why?

So. Many. Choices.

There’s AI app frameworks like Genkit, LlamaIndex, and Spring AI. There are agent frameworks like LangChain, LangGraph, Autogen, CrewAI, and more. Google recently shipped the Agent Development Kit, available for Python and Java developers. An agent built with something like ADK is basically made up of three things: a model, instructions, and tools. ADK adds sweeteners that give you a lot of flexibility. Things I like about ADK:

- Support for multiple agent patterns

- Flexible tools support, including function tools, agent tools, and MCP

- Built-in tools like Google Search

- Integrations with the Agent2Agent Protocol

- Useful support for session state and long-term memory

- Straightforward evaluations

- Runtime-agnostic code that you can deploy anywhere

- Good ecosystem, samples, and docs

And look, I like it because my employer invests in it. So, that’s a big factor. I also wanted to build agents in both Python and Java, and this made ADK a great choice.

Don’t get married to any framework, but learn the fundamentals of tool use, memory management, and agent patterns.

Choice #4 – How should I use tools in the appointment agent?

I suspect that tool selection will be a fascinating area for many builders in the years ahead. In this scenario, I had some decisions to make.

I don’t want to book any roof repairs on rainy days. But where can I get the weather forecast from? I chose the built-in Google Search tool instead of trying to find some weather API on the internet.

weather_agent = Agent(

name="weather_agent",

model="gemini-2.0-flash",

description=(

"Agent answers questions about the current and future weather in any city"

),

instruction=(

"You are an agent for Seroter Roofing. You can answer user questions about the weather in their city right now or in the near future"

),

tools=[google_search],

)

For interacting with my existing appointments API, what’s the right tool choice? Using the OpenAPI tool baked into the ADK, I can just hand the agent an OpenAPI spec and it’ll figure out the right functions to call. For retrieving open appointment times, that’s a straightforward choice.

openapi_spec = openapi_spec_template.replace("{API_BASE_URL}", config.API_BASE_URL)

toolset = OpenAPIToolset(spec_str=openapi_spec, spec_str_type="json")

api_tool_get_appointments = toolset.get_tool("get_available_appointments")

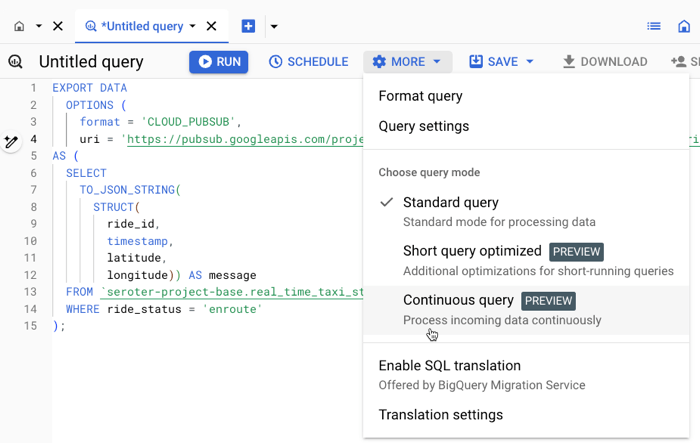

But what about booking appointments? While that’s also an API operation, I want to piggyback a successful booking with a message to Google Cloud Pub/Sub that downstream subscribers can read from. That’s not part of the appointments API (nor should it be). Instead, I think a function tool makes sense here, where I manually invoke the appointments API, and then make as subsequent call to Pub/Sub.

def add_appointment(customer: str, slotid: str, address: str, services: List[str], tool_context: ToolContext) -> dict:

"""Adds a roofing appointment by calling the booking API and logs the conversation history.

This function serves as a tool for the agent. It orchestrates the booking process by:

1. Calling the internal `_book_appointment_api_call` function to make the actual API request.

2. If the booking is successful, it retrieves the conversation history from the

`tool_context` and logs it to a Pub/Sub topic via `_log_history_to_pubsub`.

Args:

customer: The name of the customer.

slotid: The ID of the appointment slot to book.

address: The full address for the appointment.

services: A list of services to be booked for the appointment.

tool_context: The context provided by the ADK, containing session information.

Returns:

A dictionary containing the booking confirmation details from the API,

or an error dictionary if the booking failed.

"""

booking_response = _book_appointment_api_call(customer, slotid, address, services)

if "error" not in booking_response:

history_list: List[Event] = tool_context._invocation_context.session.events # type: ignore

_log_history_to_pubsub(history_list)

return booking_response

Choice #5 – When/how do I separate agent boundaries?

There’s a good chance that an agentic app has more than one agent. Stuffing everything into a single agent with a complex prompt and a dozen tools seems … suboptimal.

But multi-agent doesn’t have to mean you’re sliding into a distributed system. You can include multiple agents in the same process space and deployment artifact. The Sequential Agent pattern in the ADK makes it simple to define distinct agents that run one and at time. So it seems wise to think of service boundaries for your agents, and only make a hard split when the context changes.

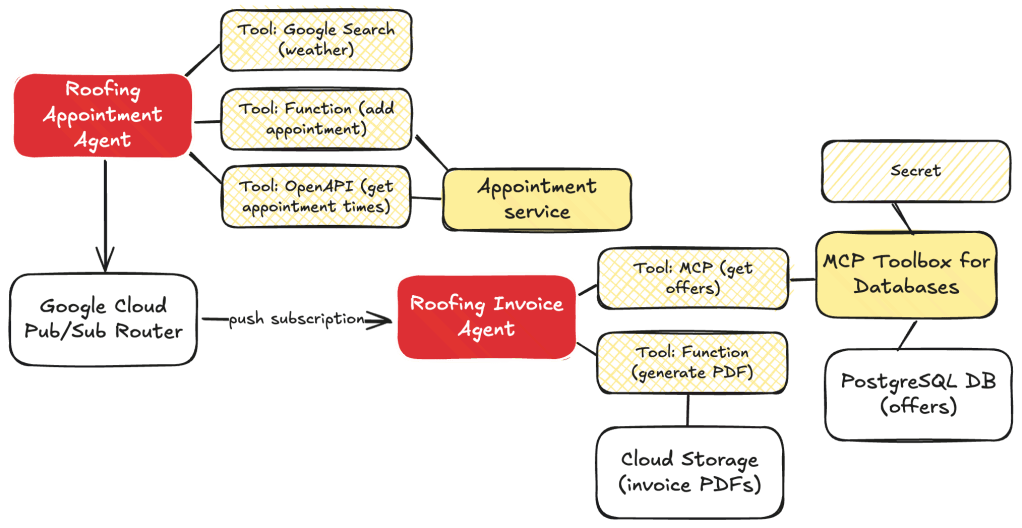

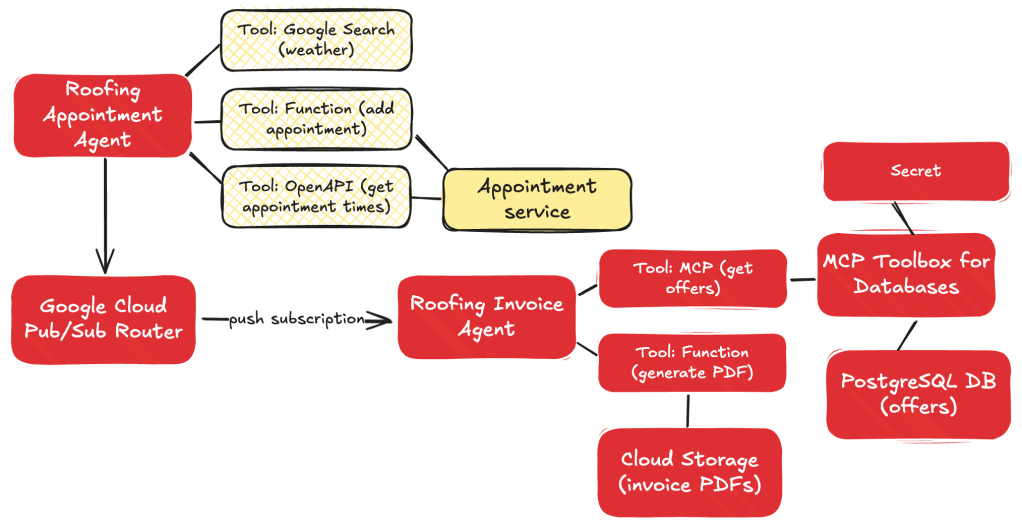

For me, that meant one set of agents handling all the appointment stuff, and another distinct set of agents that worked on invoices. These don’t depend on each other, and should run separately. Both sets of agents use the Sequential Agent pattern.

The appointment agent has sub-agents to look up the weather, and uses that agent as a tool within the primary root agent.

The invoicing agent is more complex with sub-agents to build up HTML out of the chat history, another agent that looks up the best promotional offers to attach to the invoice, and a final agent that generates a PDF.

private SequentialAgent createInvoiceAgent(

PdfTool pdfTool,

String mcpServerUrl,

Resource htmlGeneratorPrompt,

Resource bestOfferPrompt,

Resource pdfWriterPrompt

) {

String modelName = properties.getAgent().getModelName();

LlmAgent htmlGeneratorAgent = LlmAgent.builder().model(modelName).name("htmlGeneratorAgent").description("Generates an HTML invoice from conversation data.").instruction(resourceToString(htmlGeneratorPrompt)).outputKey("invoicehtml").build();

List<BaseTool> mcpTools = loadMcpTools(mcpServerUrl);

LlmAgent bestOfferAgent = LlmAgent.builder().model(modelName).name("bestOfferAgent").description("Applies the best offers available to the invoice").instruction(resourceToString(bestOfferPrompt)).tools(mcpTools).outputKey("bestinvoicehtml").build();

FunctionTool generatePdfTool = FunctionTool.create(PdfTool.class, "generatePdfFromHtml");

LlmAgent pdfWriterAgent = LlmAgent.builder().model(modelName).name("pdfWriterAgent").description("Creates a PDF from HTML and saves it to cloud storage.").instruction(resourceToString(pdfWriterPrompt)).tools(List.of(generatePdfTool)).build();

return SequentialAgent.builder().name(properties.getAgent().getAppName()).description("Execute the complete sequence to generate, improve, and publish an PDF invoice to Google Cloud Storage.").subAgents(htmlGeneratorAgent, bestOfferAgent, pdfWriterAgent).build();

}

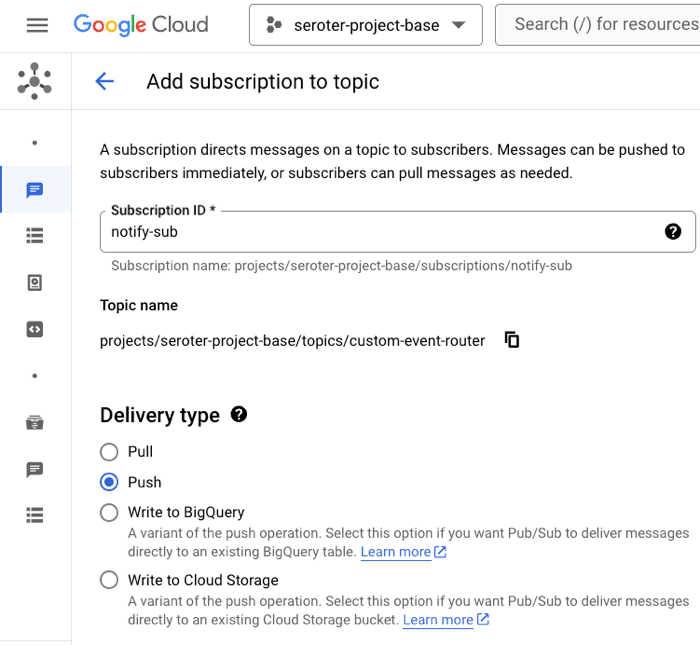

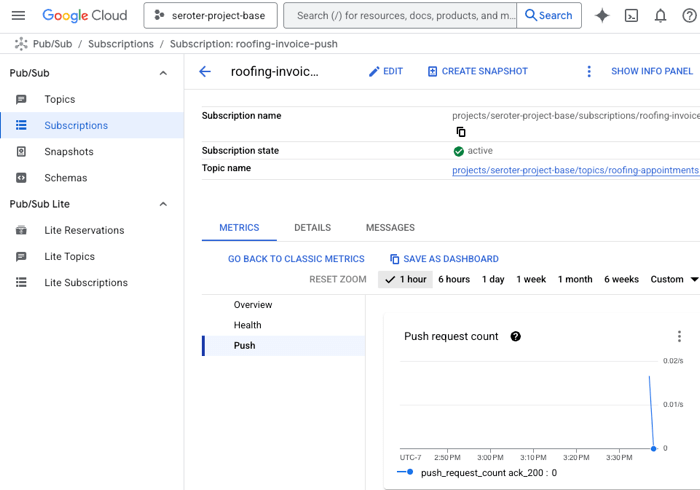

How should I connect these agents? I didn’t want hard-coded links between the services, as they can operate async and independently. You could imagine other services being interested in a booking too. So I put Google Cloud Pub/Sub in the middle. I used a push notification (to the invoice agent’s HTTP endpoint), but I’ll probably refactor it and make it a pull subscription that listens for work.

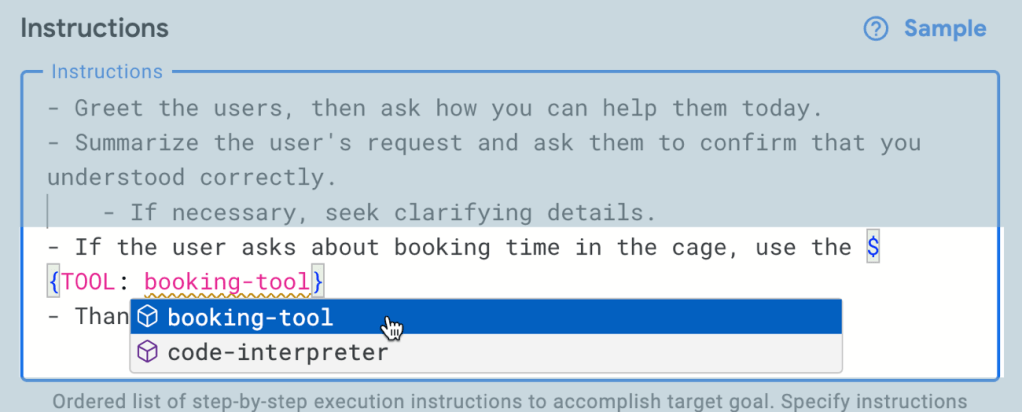

Choice #6 – What’s needed in my agent instructions?

I’m getting better at this. Still not great. But I’m using AI to help me, and learning more about what constraints and direction make the biggest impact.

For the booking agent, my goal was to collect all the data needed, while factoring in constraints such as weather. My agent instructions here included core principles, operational steps, the must-have data to collect, which decisions to make, and how to use the available tools.

root_agent = Agent(

name="root_agent",

model="gemini-2.5-flash",

description="This is the starting agent for Seroter Roofing and customers who want to book a roofing appointment",

instruction=(

"""

You are an AI agent specialized in booking roofing appointments. Your primary goal is to find available appointments for roofing services, and preferably on days where the weather forecast predicts dry weather.

## Core Principles:

* **Information First:** You must gather the necessary information from the user *before* attempting to use any tools.

* **Logical Flow:** Follow the steps outlined below strictly.

* **Professional & Helpful:** Maintain a polite, professional, and helpful tone throughout the interaction.

## Operational Steps:

1. **Greeting:**

* Start by politely greeting the user and stating your purpose (booking roofing appointments).

* *Example:* "Hello! I can help you book a roofing appointment. What kind of service are you looking for today?"

2. **Information Gathering:**

* You need two key pieces of information from the user:

* **Type of Service:** What kind of roofing service is needed? (e.g., repair, replacement, inspection, estimate)

* **Service Location:** What city is the service required in?

* Ask for this information clearly if the user doesn't provide it upfront. You *cannot* proceed to tool usage until you have both the service type and the city.

* *Example follow-up:* "Great, and in which city is the property located?"

3. **Tool Usage - Step 1: Check Appointment Availability (Filtered):**

* Get information about available appointment times:

* **[Use Tool: Appointment availability]** for the specified city.

* **Crucially:** When processing the results from the appointment tool, **filter** the available appointments to show *only* those that fall on the specific dates without rain in the forecast. You should also consider the service type if the booking tool supports filtering by type.

4. **Tool Usage - Step 2: Check Weather Forecast:**

* Once you have the service type and city, your next action is to check the weather.

* **[Use Tool: 7-day weather forecast]** for the specified city.

* Analyze the forecast data returned by the tool. Identify which days within the next 7 days are predicted to be 'sunny' or at least dry. Be specific about what constitutes 'dry' based on the tool's output.

5. **Decision Point 1: Are there Appointments on Dry Days?**

* If the appointment availability tool returns available slots *specifically* on the identified dry days:

* Present these available options clearly to the user, including the date, time, and potentially the service type (if applicable).

* Explain that these options meet the dry weather preference.

* Prompt the user to choose an option to book.

* *Example:* "Great news! The forecast for [City] shows dry weather on [Date 1], [Date 2], etc. I've checked our schedule and found these available appointments on those days: [List appointments]."

* If the appointment availability tool returns slots, but *none* of them fall on the identified sunny days (or if the tool returns no slots at all):

* Inform the user that while there are dry days coming up, there are currently no appointments available on those specific dry dates within the next 7 days.

* Explain that your search was limited to the dry days based on the forecast.

* Suggest they might want to try a different service type (if relevant) or check back later as availability changes.

* *Example:* "While the forecast for [City] does show some dry days coming up, I wasn't able to find any available appointments specifically on those dates within the next week. Our schedule on sunny days is quite popular. Please try again in a few days, as availability changes, or let me know if you need a different type of service."

6. **Confirmation/Booking (If Applicable):**

* Be sure to get the full name and full address of the location for the appointment.

**Tools**

You have access to the following tools to assist you:

`weather_agent`: use this tool to find the upcoming weather forecast and identify rainy days

`api_tool_get_appointments -> json`: use this OpenAPI tool to answer any questions about available appointments

`add_appointment(customer: str, slotid: str, address: str, services: List[str]) -> dict`: use this tool to add a new appointment

"""

),

tools=[agent_tool.AgentTool(weather_agent), api_tool_get_appointments, tools.add_appointment],

)

The invoicing agent had a more complex prompt as I wanted to shape the blob of chat history into a structured JSON and then into valid HTML. Of course, I could have (should have?) structured the raw data before it left the original agent, but I wanted try it this way. My agent instructions show an example of the preferred JSON, and also the valid HTML structure.

**Role:** You are a specialized agent designed to generate an HTML invoice from a successful appointment booking history.

**Task:** Process the entire user prompt, which contains conversation history in a JSON format. Your goal is to create a complete HTML invoice based on the details found in that JSON.

[...]

4. **Invoice JSON Structure:** The JSON invoice you internally generate **must** strictly adhere to the format provided in the example below. Do not add extra fields or change field names. Ensure numbers are formatted correctly (e.g., 100.00, 0.00).

```json

{

"invoiceNumber": "INV-BOOKING-[Current Date YYYYMMDD]", // Generate based on date

"issueDate": [YYYY, M, D], // Current Date

"dueDate": [YYYY, M, D], // Current Date + 30 days

"customerName": "[Extracted Customer Name]",

"customerAddress": "[Extracted Customer Address]",

"items": [

{

"description": "[Description of Booked Service]",

"quantity": 1,

"unitPrice": [Price of Service],

"lineTotal": [Price of Service]

}

],

"subtotal": [Price of Service],

"taxAmount": 0.00,

"summary": "Invoice for booked [Service Name]",

"totalAmount": [Price of Service]

}

```

[...]

7. ** Create an HTML string based on the example structure here **

```html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<title>Seroter Roofing Invoice</title>

<style type="text/css">

body { font-family: sans-serif; margin: 20px; }

h1 { color: navy; }

.header, .customer-info, .summary-block, .footer { margin-bottom: 20px; }

.invoice-details { margin-top: 20px; padding: 10px; border: 1px solid #ccc; }

.invoice-details p { margin: 5px 0; }

table { width: 100%; border-collapse: collapse; margin-top: 20px; }

.summary-block { padding: 10px; border: 1px dashed #eee; background-color: #f9f9f9; }

th, td { border: 1px solid #ddd; padding: 8px; text-align: left; }

th { background-color: #f2f2f2; }

.text-right { text-align: right; }

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Invoice</h1>

<div class="header">

<p><strong>Invoice Number:</strong>INV-001</p>

<p><strong>Date Issued:</strong>January 01, 2024</p>

<p><strong>Date Due:</strong>January 15, 2024</p>

</div>

<div class="customer-info">

<h2>Bill To:</h2>

<p>Customer Name</p>

<p>123 Customer Street, Denver, CO 80012</p>

</div>

<div class="summary-block">

<h2>Summary</h2>

<p>Details about the appointment and order...</p>

</div>

<table>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>Description</th>

<th>Quantity</th>

<th>Unit Price</th>

<th>Line Total</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr >

<td>Sample Item</td>

<td class="text-right">1</td>

<td class="text-right">10.00</td>

<td class="text-right">10.00</td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>

<div class="invoice-details">

<p class="text-right"><strong>Subtotal:</strong>>0.00</p>

<p class="text-right"><strong>Tax:</strong>0.00</p>

<p class="text-right"><strong>Total Amount:</strong> <strong>$123.45</strong></p>

</div>

<div class="footer">

<p>Thank you for your business!</p>

</div>

</body>

</html>

```

Doing this “context engineering” well is important. Think through the instructions, data, and tools that you’re giving an agent to work with.

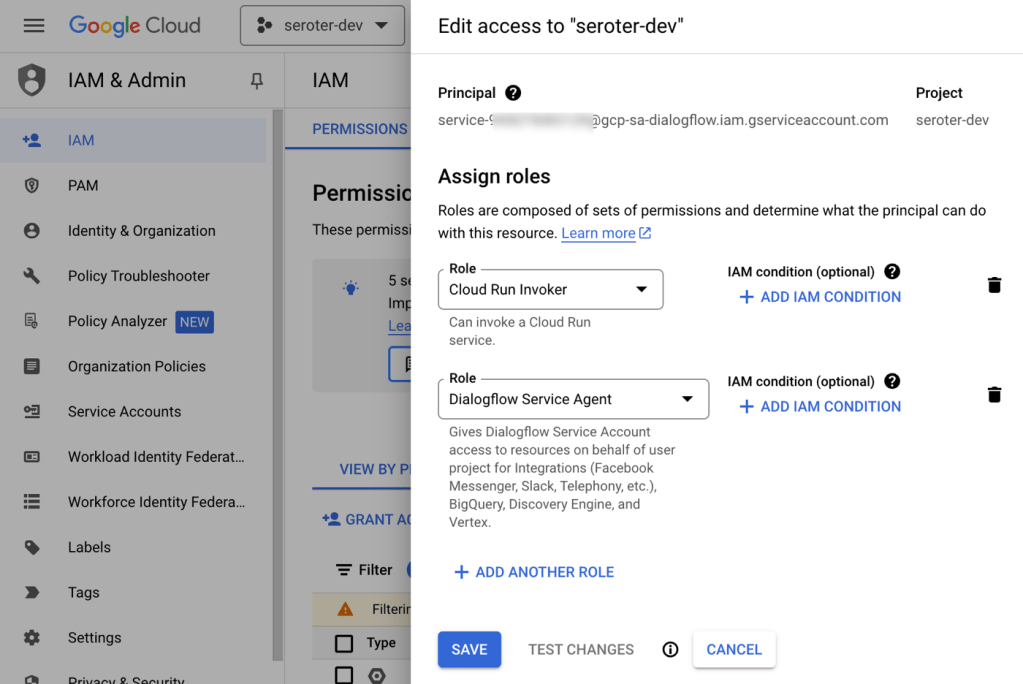

Choice #7 – What’s the right approach to accessing Cloud services?

My agent solution sent data to Pub/Sub (addressed above), but also relied on data sitting in a PostgreSQL database. And PDF blobs sitting in Cloud Storage.

I had at least three implementation options here for PostgreSQL and Cloud Storage:

- Function calling. Use functions that call the Cloud APIs directly, and leverage those functions as tools.

- Model Context Protocol (MCP). Use MCP servers that act as API proxies for the LLM to use

- YOLO mode. Ask the LLM to figure out the right API call to make for the given service.

The last option works (mostly), but would be an absurd choice to make in 99.98% of situations.

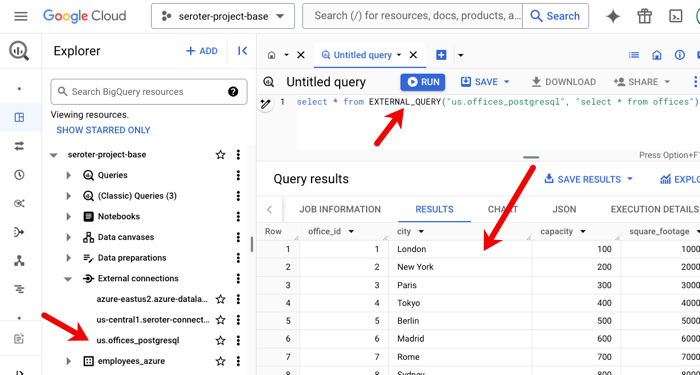

The appointment agent calls the Pub/Sub API directly by using that encompassing function as a tool. For the database access, I chose MCP. The MCP Toolbox for Databases is open source and fairly simple to use. It saves me from a lot of boilerplate database access code.

private List<BaseTool> loadMcpTools(String mcpServerUrl) {

try {

SseServerParameters params = SseServerParameters.builder().url(mcpServerUrl).build();

logger.info("Initializing MCP toolset with params: {}", params);

McpToolset.McpToolsAndToolsetResult result = McpToolset.fromServer(params, new ObjectMapper()).get();

if (result.getTools() != null && !result.getTools().isEmpty()) {

logger.info("MCP tools loaded: {}", result.getTools().size());

return result.getTools().stream().map(mcpTool -> (BaseTool) mcpTool).collect(Collectors.toList());

}

} catch (Exception e) {

logger.error("Error initializing MCP toolset", e);

}

return new ArrayList<>();

}

When creating the PDF and adding it to Cloud Storage, I decided to use a robust function that I passed to the agent as a tool.

private Map<String, Object> generatePdfFromHtmlInternal(String htmlContent) throws IOException {

if (htmlContent == null || htmlContent.trim().isEmpty()) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("HTML content cannot be null or empty.");

}

try (ByteArrayOutputStream baos = new ByteArrayOutputStream()) {

ITextRenderer renderer = new ITextRenderer();

renderer.setDocumentFromString(htmlContent);

renderer.layout();

renderer.createPDF(baos);

String timestamp = LocalDateTime.now().format(DateTimeFormatter.ofPattern("yyyyMMddHHmmssSSS"));

String uniquePdfFilename = OUTPUT_PDF_FILENAME.replace(".pdf", "_" + timestamp + ".pdf");

String bucketName = properties.getGcs().getBucketName();

BlobId blobId = BlobId.of(bucketName, uniquePdfFilename);

BlobInfo blobInfo = BlobInfo.newBuilder(blobId).setContentType("application/pdf").build();

storage.create(blobInfo, baos.toByteArray());

String gcsPath = "gs://" + bucketName + "/" + uniquePdfFilename;

logger.info("Successfully generated PDF and uploaded to GCS: {}", gcsPath);

return Map.of("status", "success", "file_path", gcsPath);

} catch (DocumentException e) {

logger.error("Error during PDF document generation", e);

throw new IOException("Error during PDF document generation: " + e.getMessage(), e);

} catch (Exception e) {

logger.error("Error during PDF generation or GCS upload", e);

throw new IOException("Error during PDF generation or GCS upload: " + e.getMessage(), e);

}

}

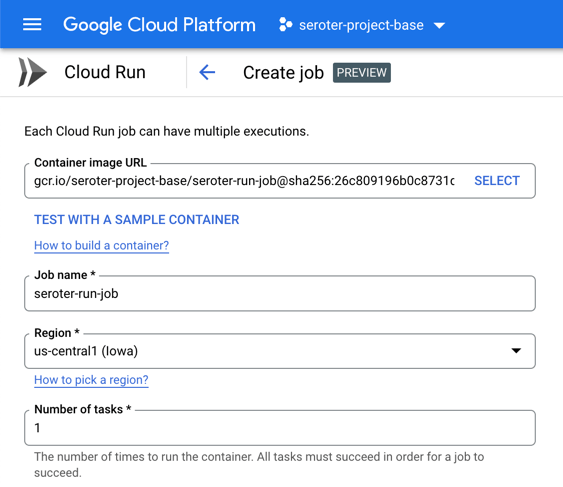

Choice #8 – How do I package up and run the agents?

This choice may depend on who the agent is for (internal or external audiences), who has to support the agent, and how often you expect to update the agent.

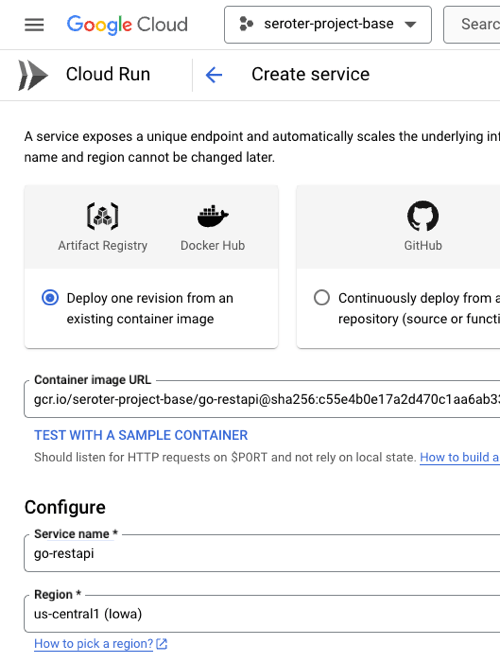

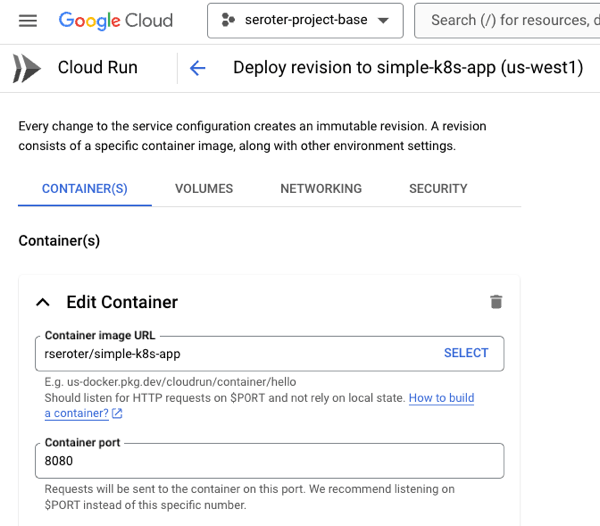

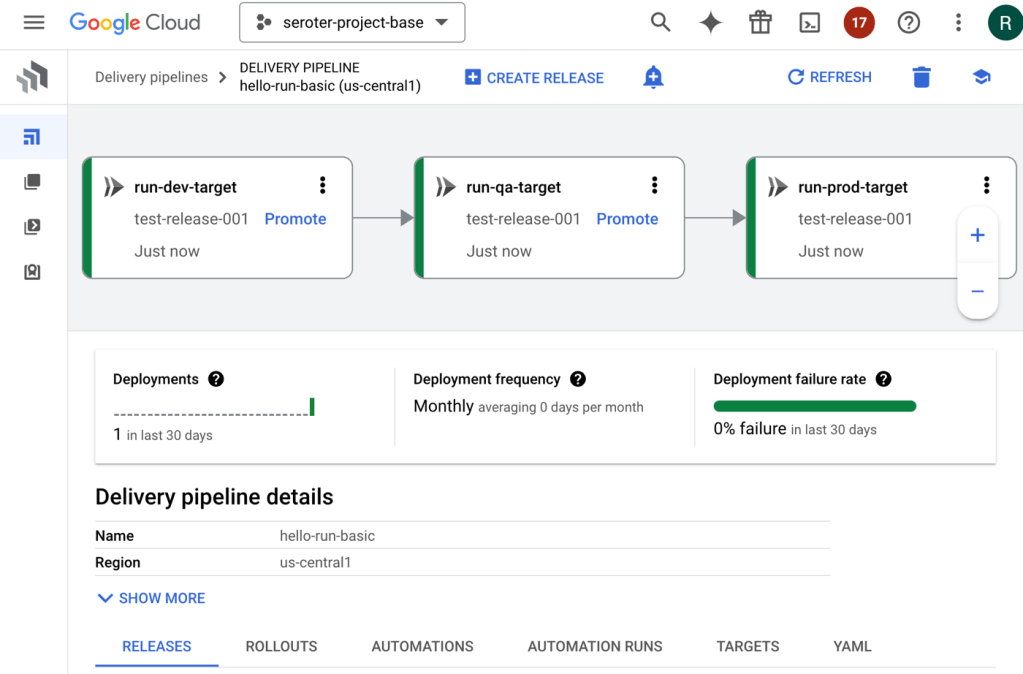

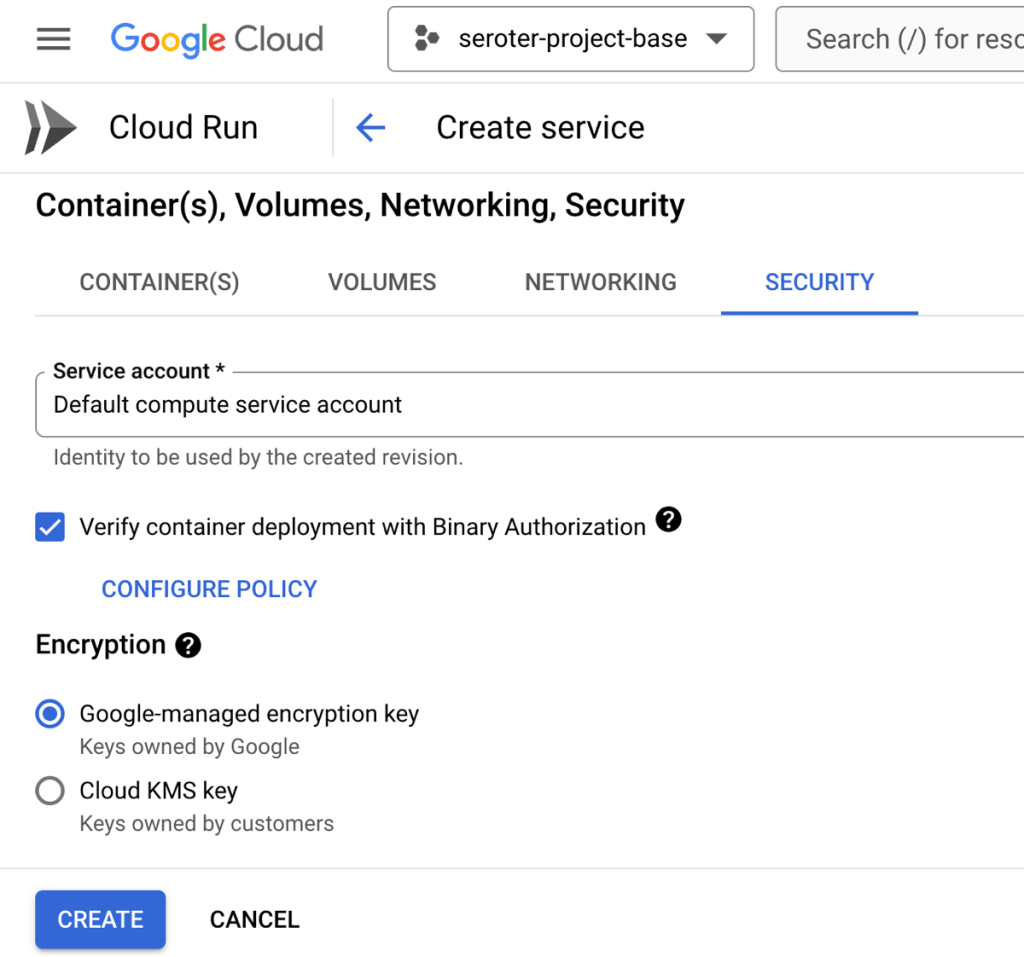

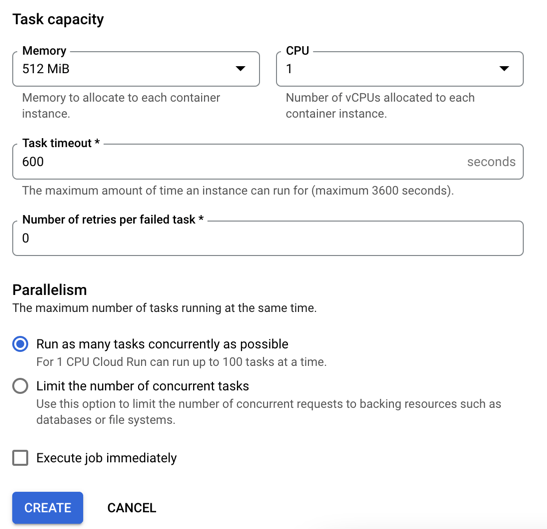

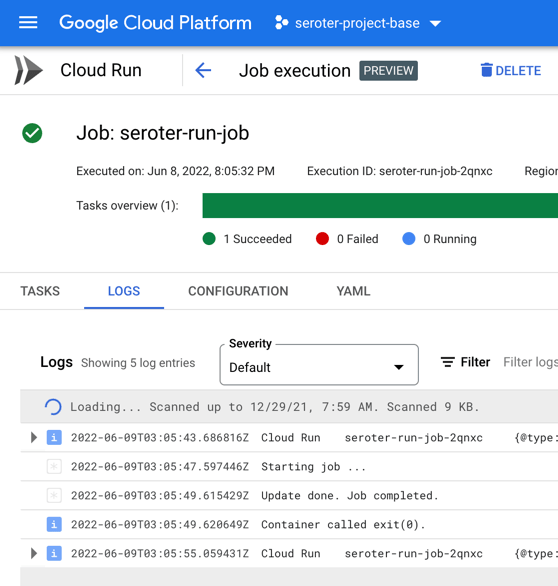

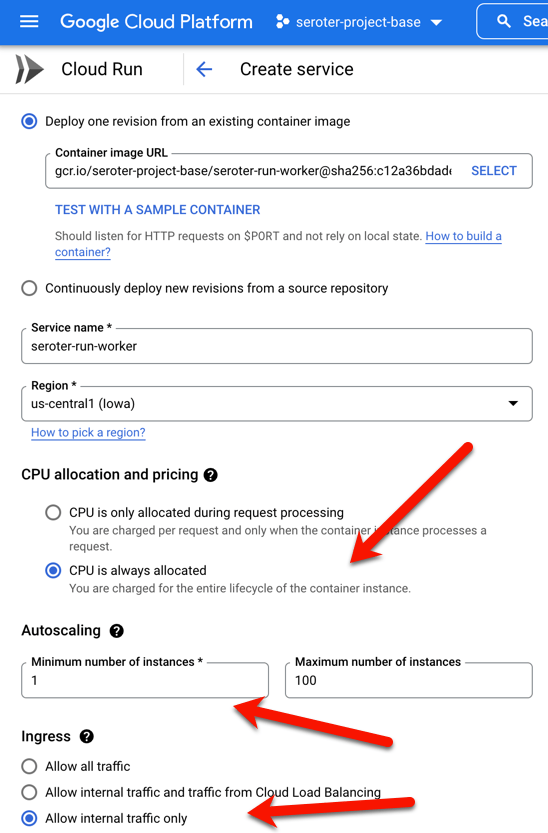

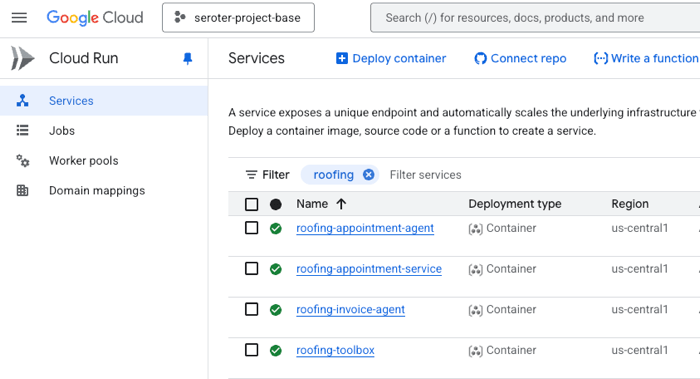

I chose to containerize the components so that I had maximum flexibility. I could have easily used the ADK CLI to deploy directly to Vertex AI Agent Engine—which comes with convenient features like memory management—but wanted more control than that. So I have Dockerfiles for each agent, and deploy them to Google Cloud Run. Here I get easy scale, tons of optional configurations, and I don’t pay for anything when the agent is dormant.

In this case, I’m just treating the agent like any other type of code. You might make a different choice based on your use case.

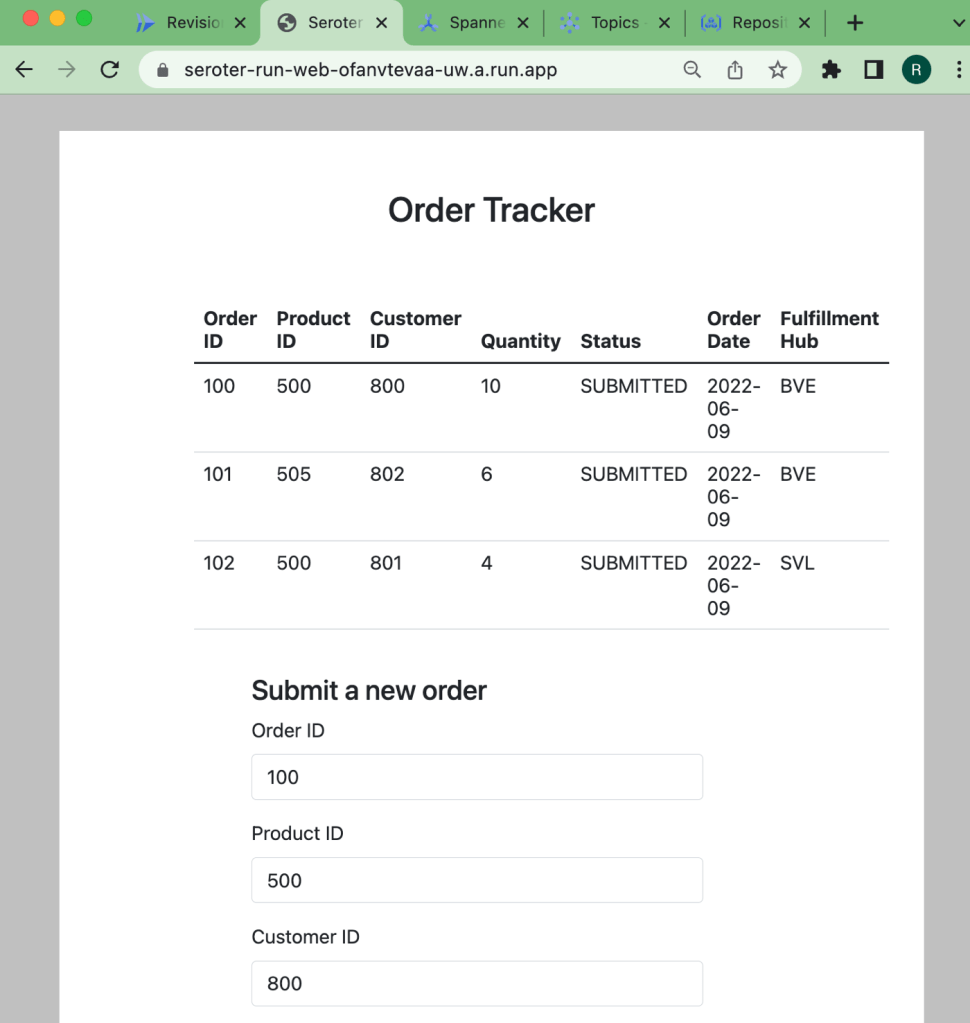

The final solution in action

Let’s run this thing through. All the source code is sitting in my GitHub repo.

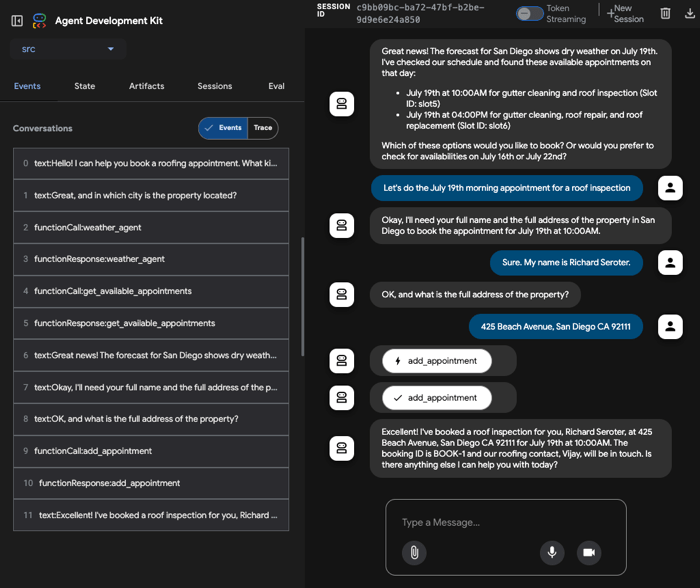

I start by opening the the appointment agent hosted in Cloud Run. I’m using the built-in ADK web UI to have a conversational chat with the initial agent. I mention that I might have a leaky roof and want an inspection or repair. The agent then follows its instructions. After checking the weather in the city I’m in, it retrieves appointments via the API. On the left, there’s a handy set of tools to trace events, do evals, and more.

At this point, I chose an available appointment, and the agent followed it’s next set of instructions. The appointment required two pieces of info (my name, and address), and wouldn’t proceed until I provided it. Once it had the data, it called the right function to make an appointment and publish a message to Pub/Sub.

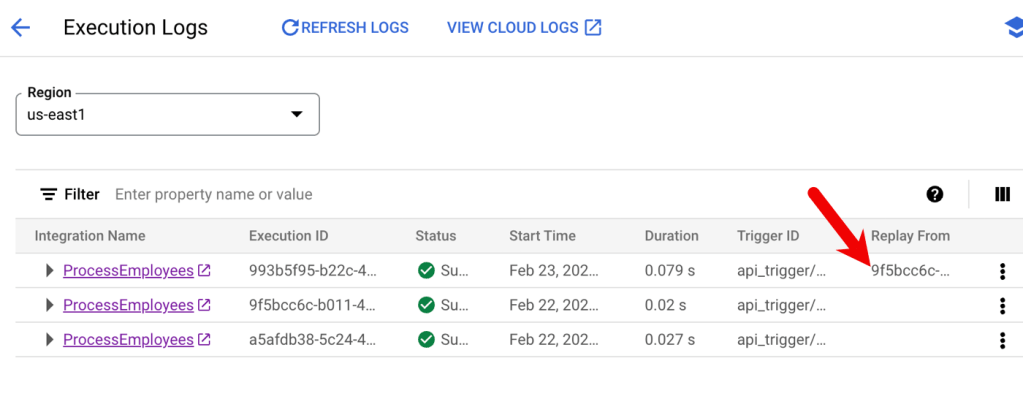

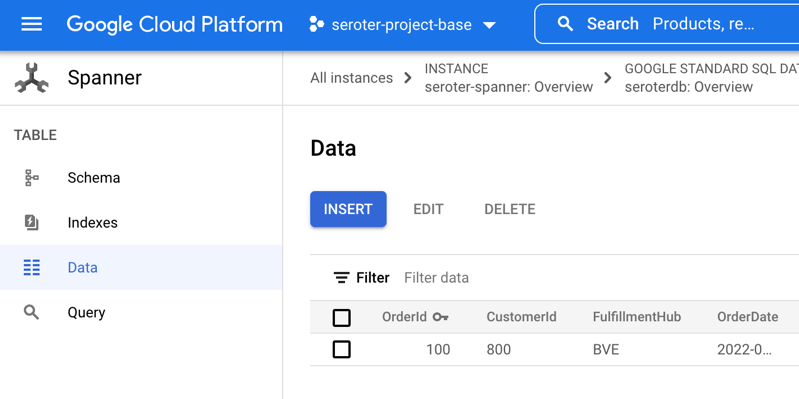

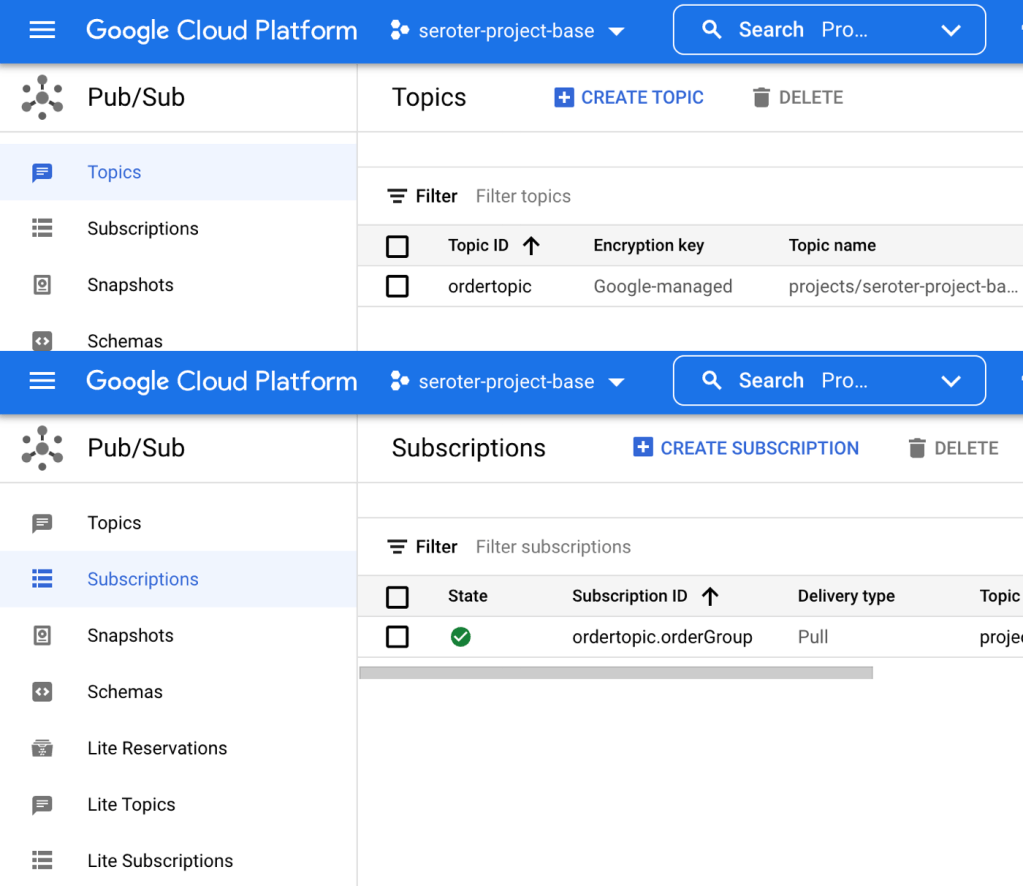

That data flowed through Google Cloud Pub/Sub, and got pushed to another agent hosted in Cloud Run.

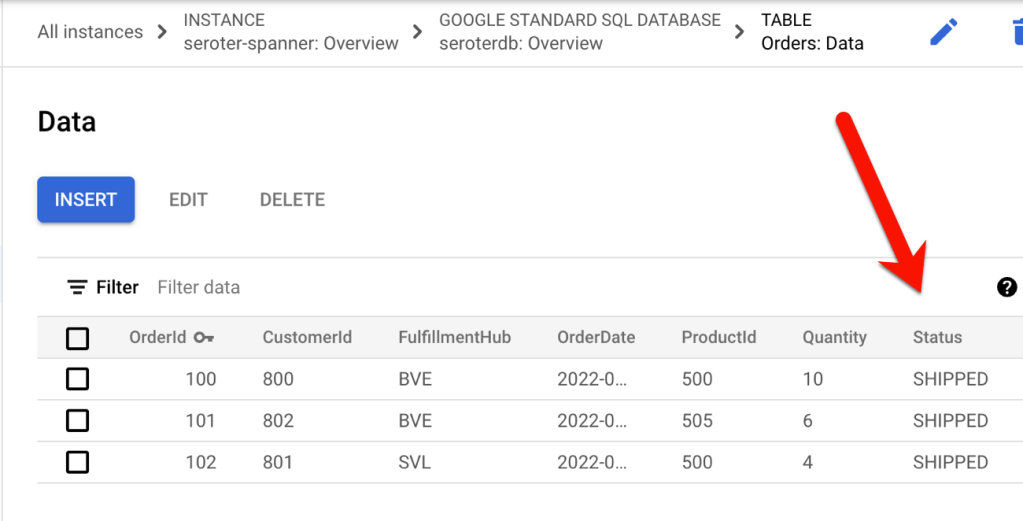

That agent immediately loaded up its MCP tools by calling the MCP server also hosted in Cloud Run. That server retrieved the list of offers for the city in question.

This agent runs unattended in the background, so there’s no chat interface or interactivity. Instead, I can track progress by reading the log stream.

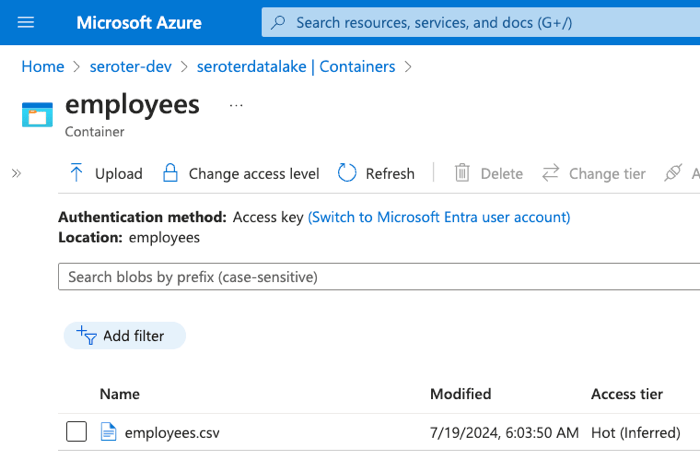

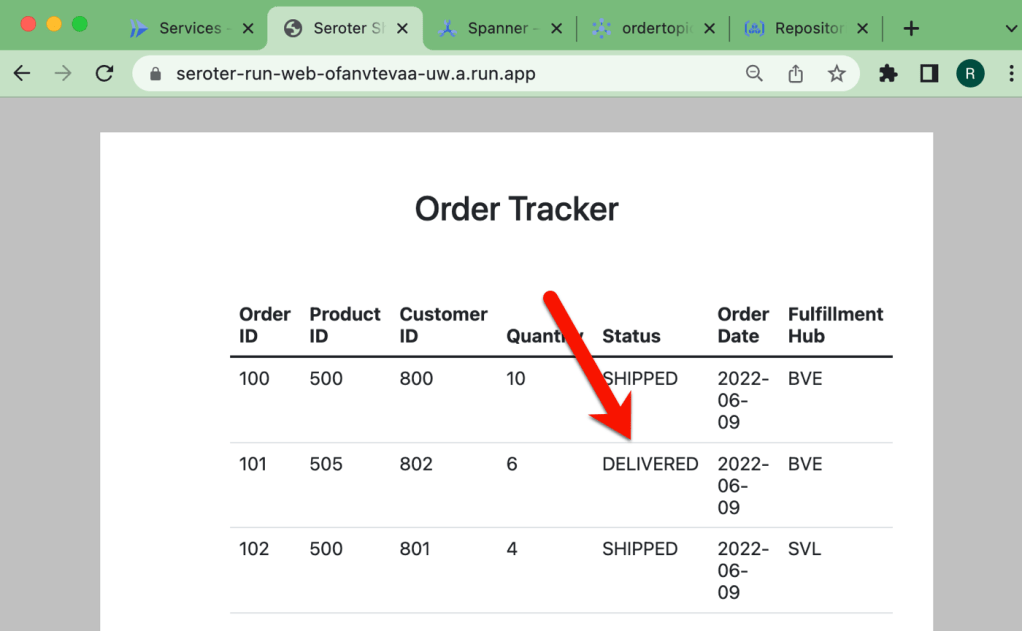

When this agent got done converting the chat blob to JSON, then creating an HTML template, and calling the MCP tools to attach offers, it wrote the final PDF to Cloud Storage.

There you go. It’s not perfect and I have improvements I want to make. Heck, the example here has the wrong date in the invoice, which didn’t happen before. So I need better instructions there. I’d like to switch the second agent from a push to a pull. It’d be fun to add some video or audio intake to the initial agent.

Nobody knows the future, but it looks we’ll be building more agents, and fewer standalone apps. APIs matter more than ever, as do architectural decisions. Make good ones!