Software is never going to be the same. Why would we go back to laborious research efforts, wasting time writing boilerplate code, and accepting so many interruptions to our flow state? Hard pass. It might not happen for you tomorrow, next month, or next year, but AI will absolutely improve your developer workflow.

Your AI-powered workflow may make use of more than one LLMs. Go for it. But we’ve done a good job of putting Gemini into nearly every stage of the new way of working. Let’s look at what you can do RIGHT NOW to build with Gemini.

- Build knowledge, plans, and prototypes with Gemini

- Build apps and agents with Gemini

- Build AI and data systems with Gemini

- Build a better day-2 experience with Gemini

- Build supporting digital assets with Gemini

Build knowledge, plans, and prototypes with Gemini

Are you still starting your learning efforts with a Google search? Amateurs 🙂 I mean, keep doing those so that we earn ad dollars. But you’ve got so many new ways to augment a basic search.

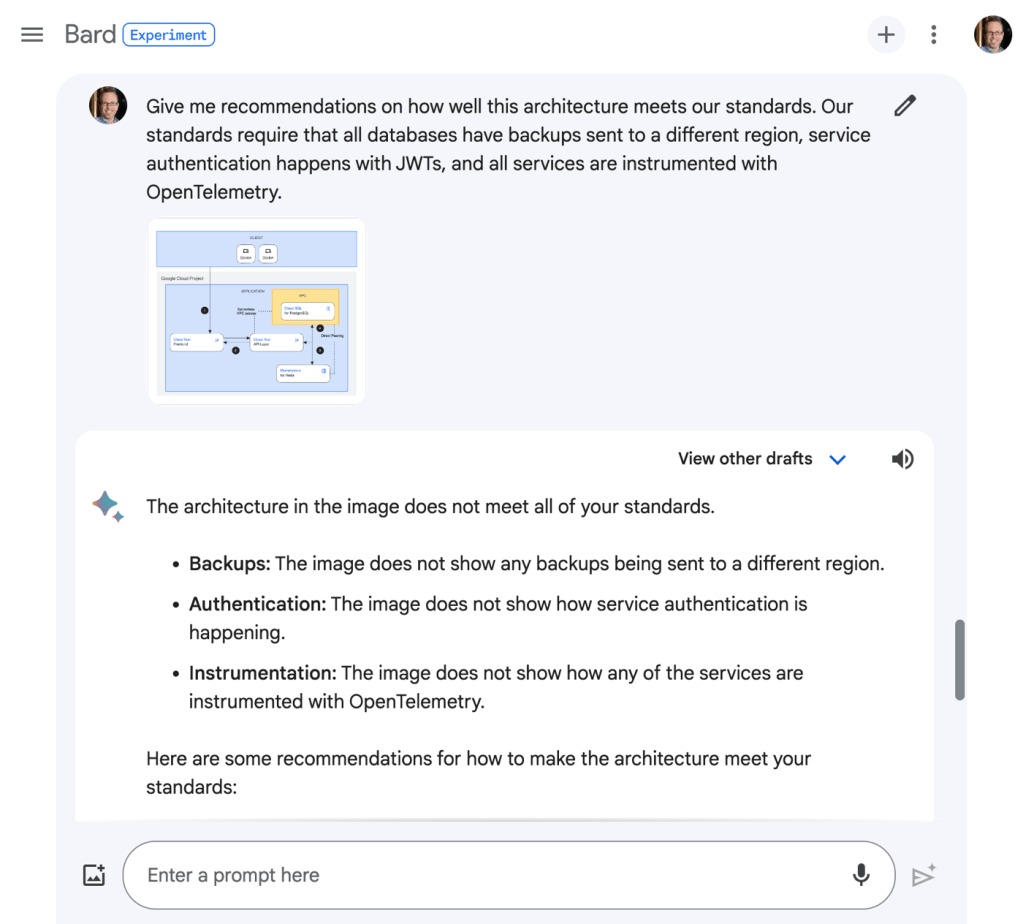

Gemini Deep Research is pretty amazing. Part of Gemini Advanced, it takes your query, searches the web on your behalf, and gives you a summary in minutes. Here I asked for help understanding the landscape of PostgreSQL providers, and it recapped results found in 240+ relevant websites from vendors, Reddit, analyst, and more.

You’ve probably heard of NotebookLM. Built with Gemini 2.0, it takes all sorts of digital content and helps you make sense of it. Including those hyper-realistic podcasts (“Audio Overviews”).

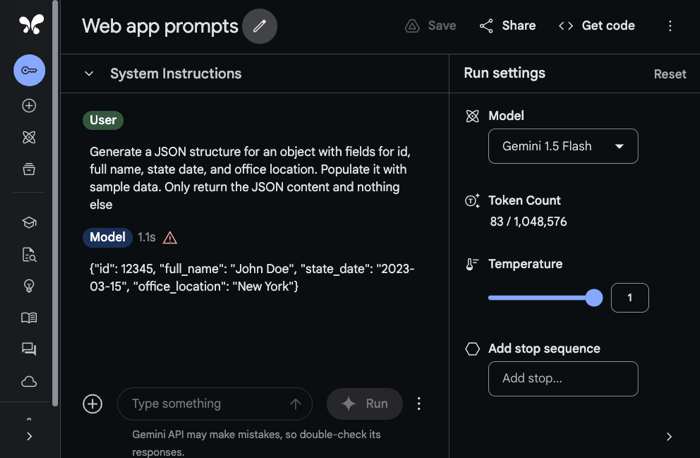

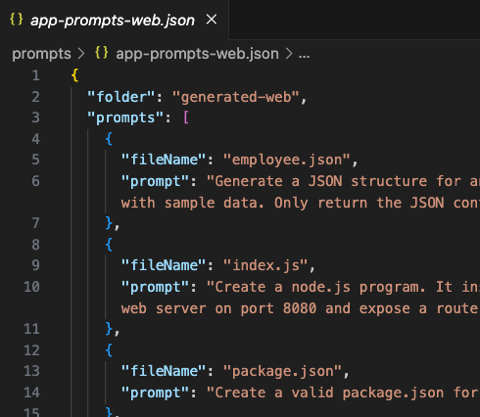

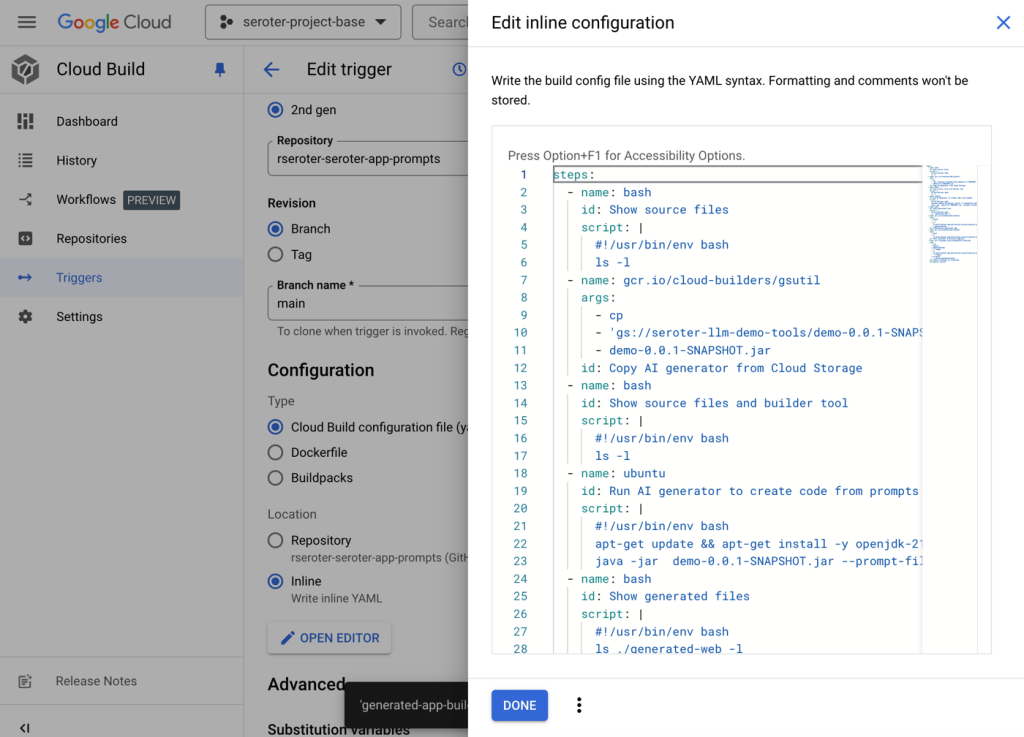

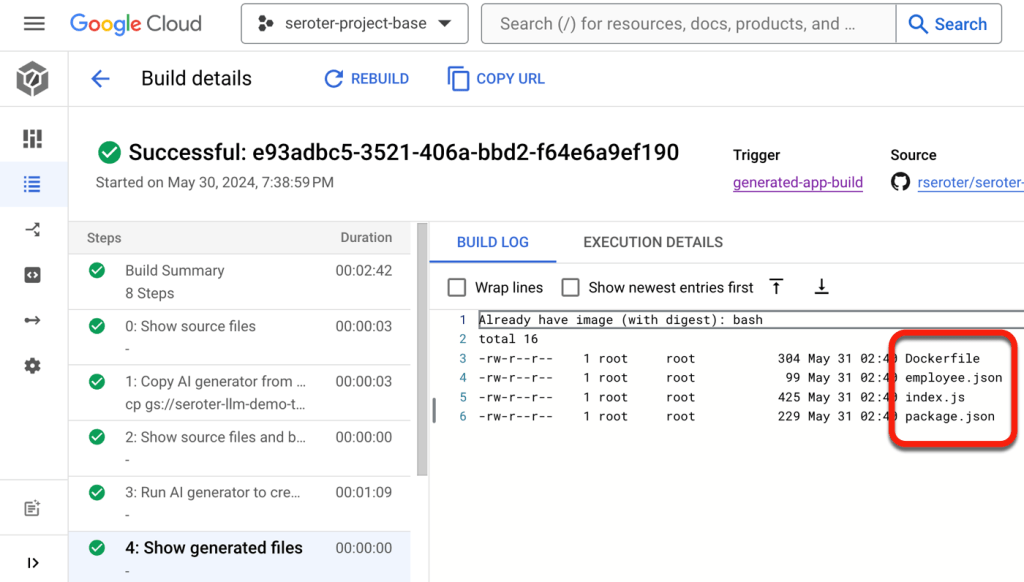

Planning your work or starting to flesh out a prototype? For free, Google AI Studio lets you interact with the latest Gemini models. Generate text, audio, or images from prompts. Produce complex codebases based on reference images or text prompts. Share your desktop and get live assistance on whatever task you’re doing. It’s pretty rad.

Google Cloud customers can get knowledge from Gemini in a few ways. The chat for Gemini Cloud Assist gives me an ever-present agent that can help answer questions or help me explore options. Here, I asked for a summary of the options for running PostgreSQL in Google Cloud. It breaks the response down by fully-managed, self-managed, and options for migration.

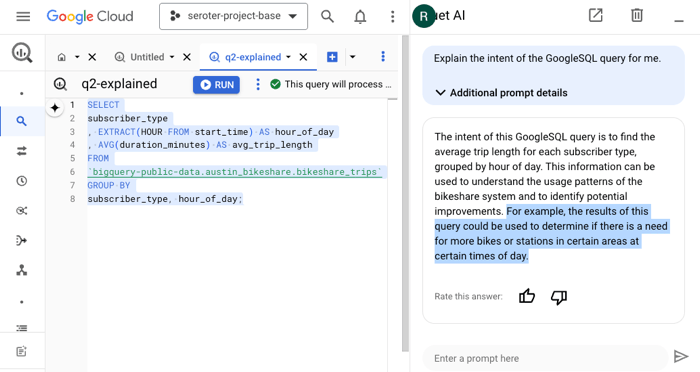

Gemini for Google Cloud blends AI-assistance into many different services. One way to use this is to understand existing SQL scripts, workflows, APIs, and more.

Trying to plan out your next bit of work? Google AI Studio or Vertex AI Studio can assist here too. In either service, you can pass in your backlog of features and bugs, maybe an architecture diagram or two, and even some reference PDFs, and ask for help planning out the next sprint. Pretty good!

Build apps and agents with Gemini

We can use Google AI Studio or Vertex AI Studio to learn things and craft plans, but now let’s look at how you’d actually build apps with Gemini.

You can work with the raw Gemini API. There are SDK libraries for Python, Node, Go, Dart, Swift, and Android. If you’re working with Gemini 2.0 and beyond, there’s a new unified SDK that works with both the Developer API and Enterprise API (Vertex). It’s fairly easy to use. I wrote a Google Cloud Function that uses the unified Gemini API to generate dinner recipes for whatever ingredients you pass in.

package function

import (

"context"

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

"os"

"github.com/GoogleCloudPlatform/functions-framework-go/functions"

"google.golang.org/genai"

)

func init() {

functions.HTTP("GenerateRecipe", generateRecipe)

}

func generateRecipe(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ctx := context.Background()

ingredients := r.URL.Query().Get("ingredients")

if ingredients == "" {

http.Error(w, "Please provide ingredients in the query string, like this: ?ingredients=pork, cheese, tortilla", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

projectID := os.Getenv("PROJECT_ID")

if projectID == "" {

projectID = "default" // Provide a default, but encourage configuration

}

location := os.Getenv("LOCATION")

if location == "" {

location = "us-central1" // Provide a default, but encourage configuration

}

client, err := genai.NewClient(ctx, &genai.ClientConfig{

Project: projectID,

Location: location,

Backend: genai.BackendVertexAI,

})

//add error check for err

if err != nil {

log.Printf("error creating client: %v", err)

http.Error(w, "Failed to create Gemini client", http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

prompt := fmt.Sprintf("Given these ingredients: %s, generate a recipe.", ingredients)

result, err := client.Models.GenerateContent(ctx, "gemini-2.0-flash-exp", genai.Text(prompt), nil)

if err != nil {

log.Printf("error generating content: %v", err)

http.Error(w, "Failed to generate recipe", http.StatusServiceUnavailable)

return

}

if len(result.Candidates) == 0 {

http.Error(w, "No recipes found", http.StatusNotFound) // Or another appropriate status

return

}

recipe := result.Candidates[0].Content.Parts[0].Text // Extract the generated recipe text

response, err := json.Marshal(map[string]string{"recipe": recipe})

if err != nil {

log.Printf("error marshalling response: %v", err)

http.Error(w, "Failed to format response", http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

w.Write(response)

}

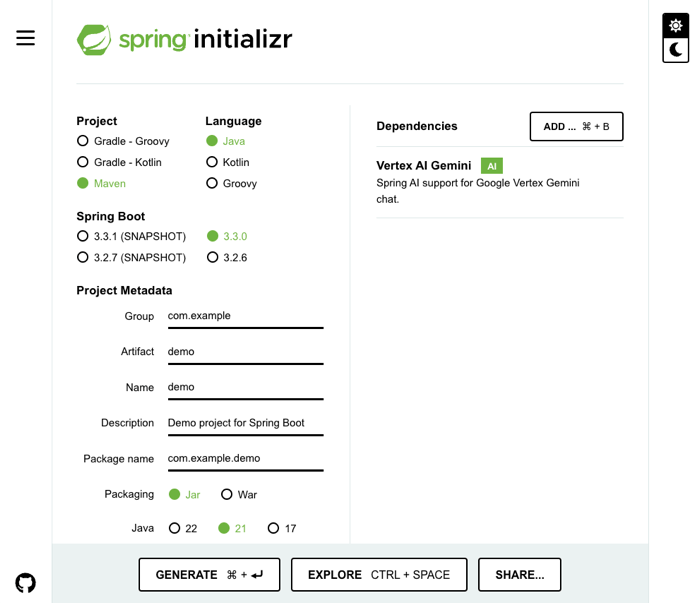

There are a lot agent frameworks out there right now. A LOT. Many of them have good Gemini support. You can build agents with Gemini using LangChain, LangChain4J, LlamaIndex, Spring AI, Firebase Genkit, and the Vercel AI SDK.

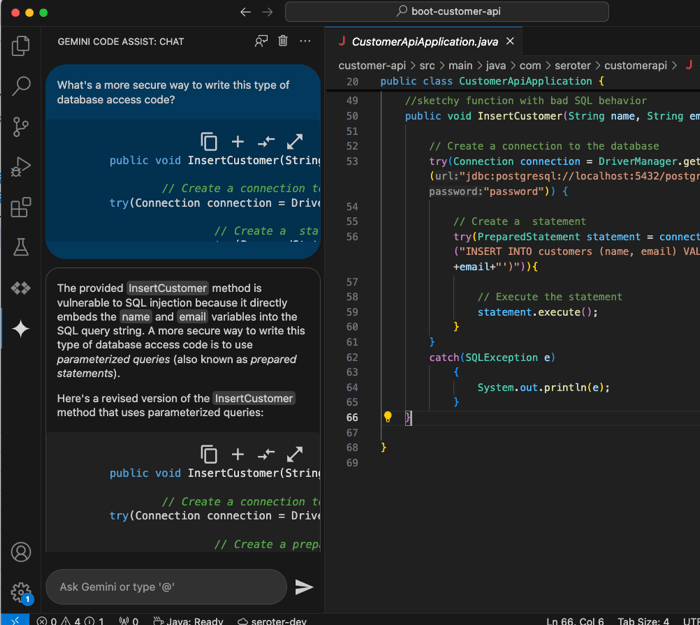

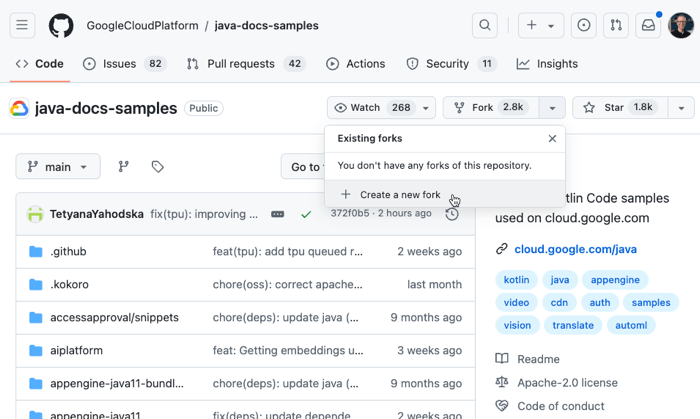

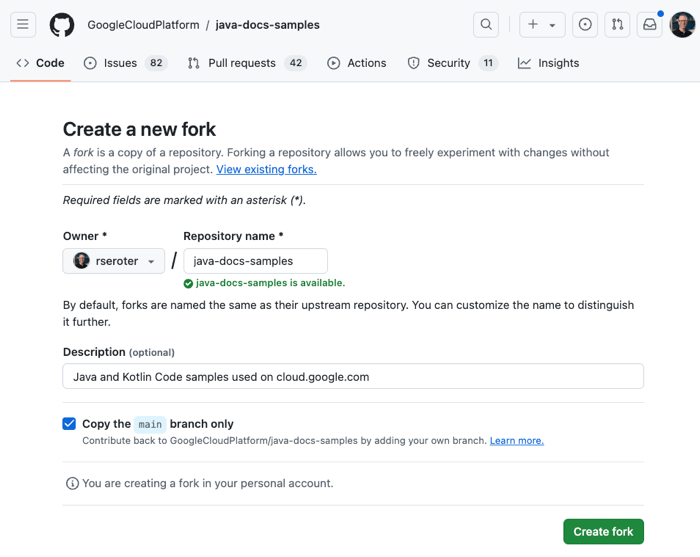

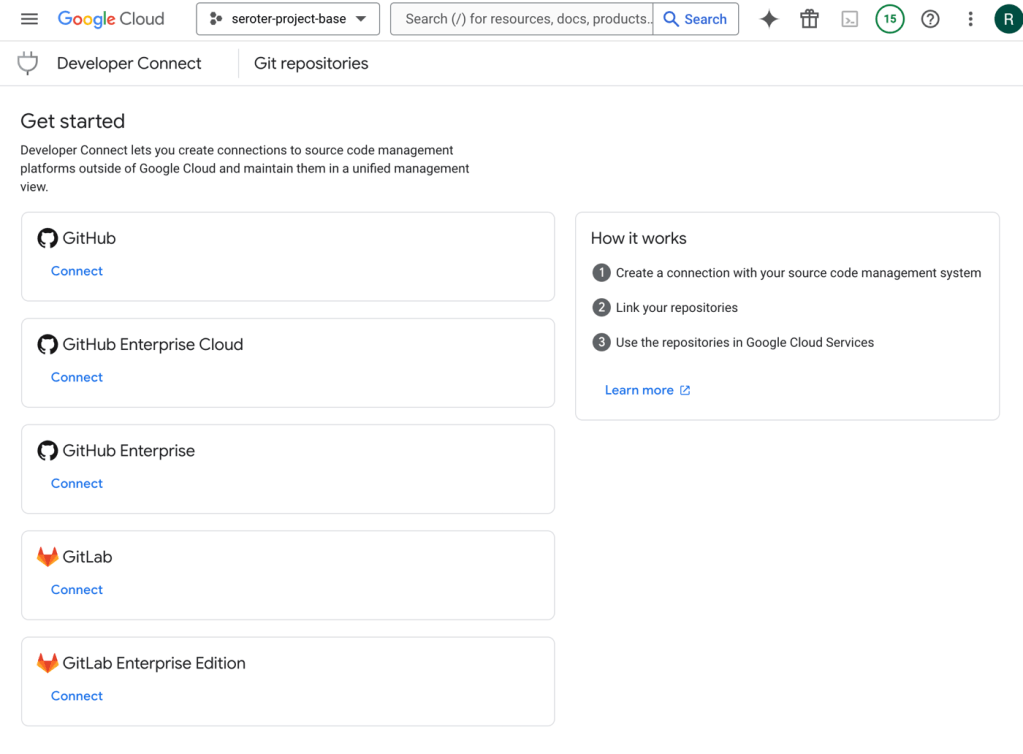

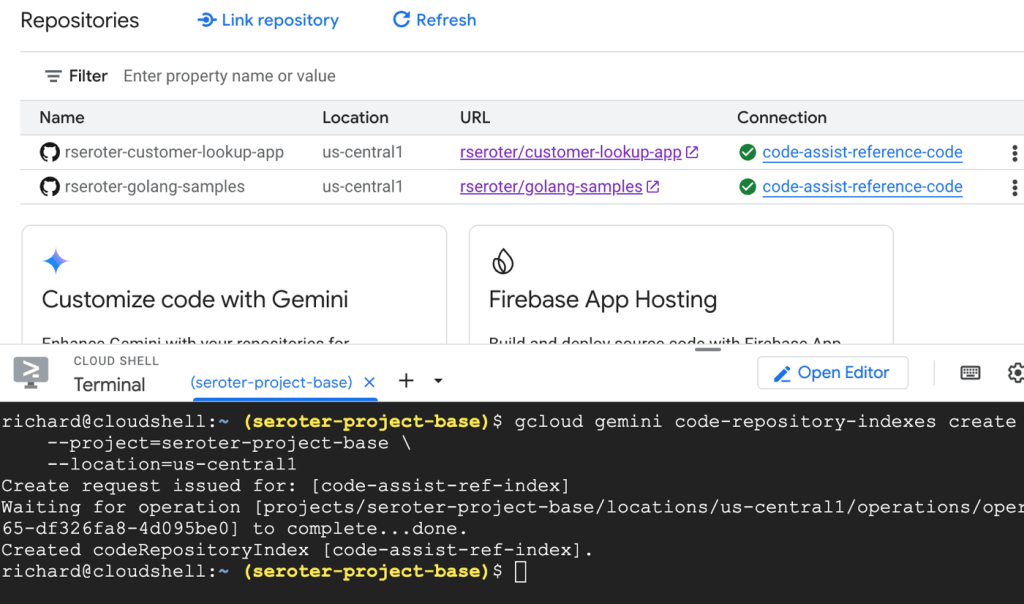

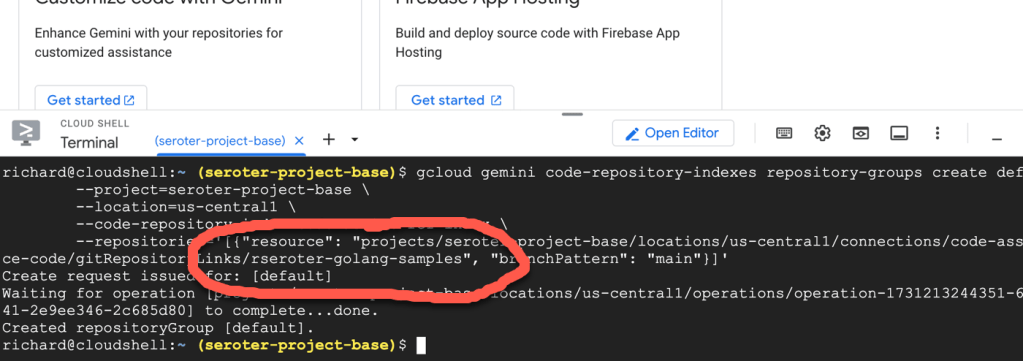

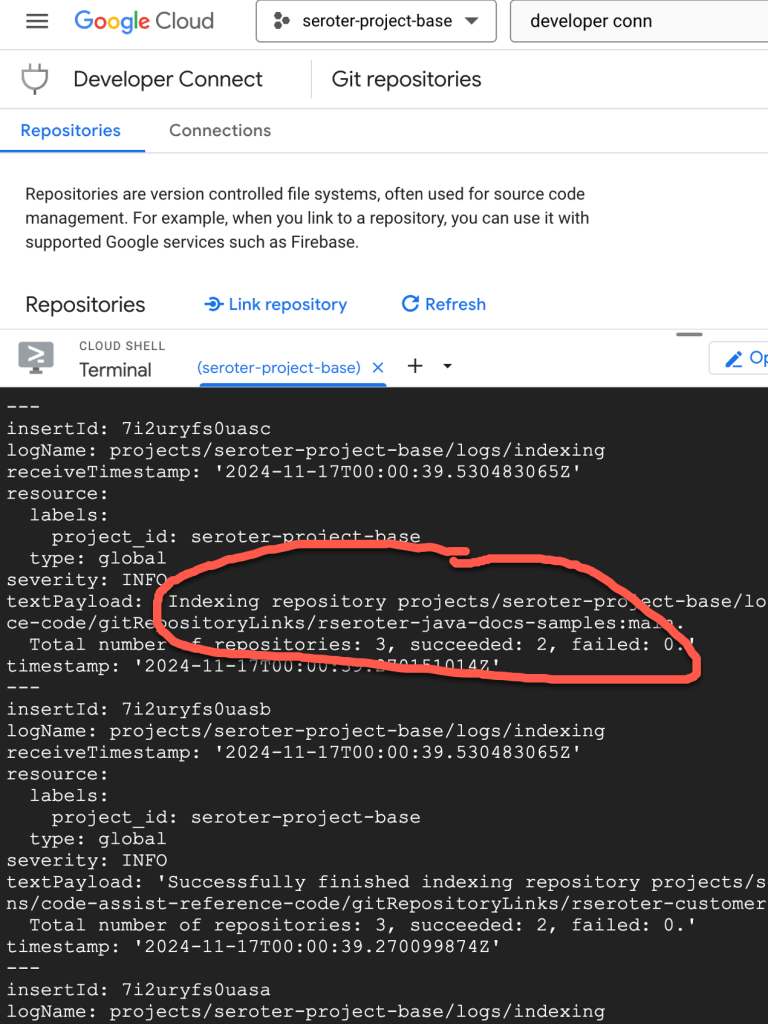

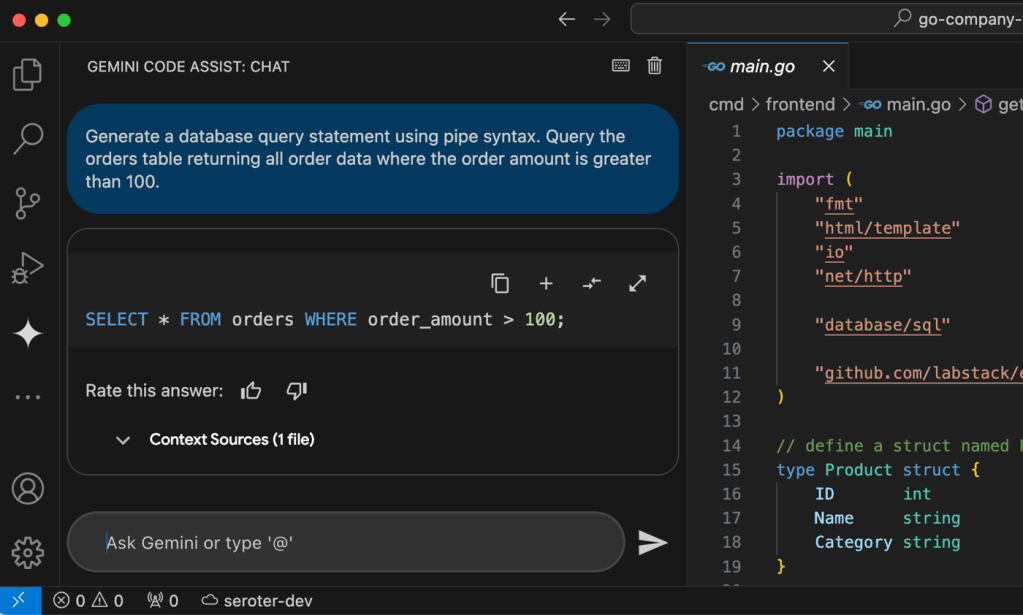

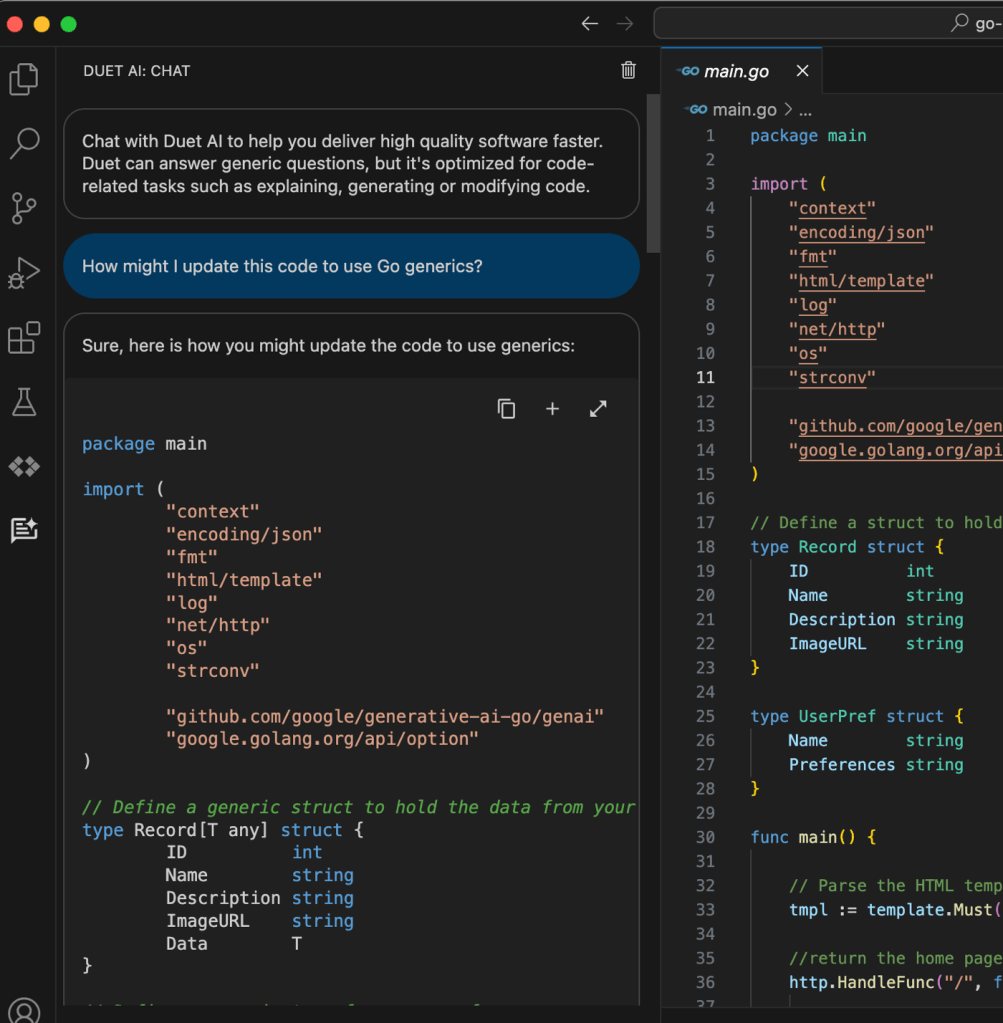

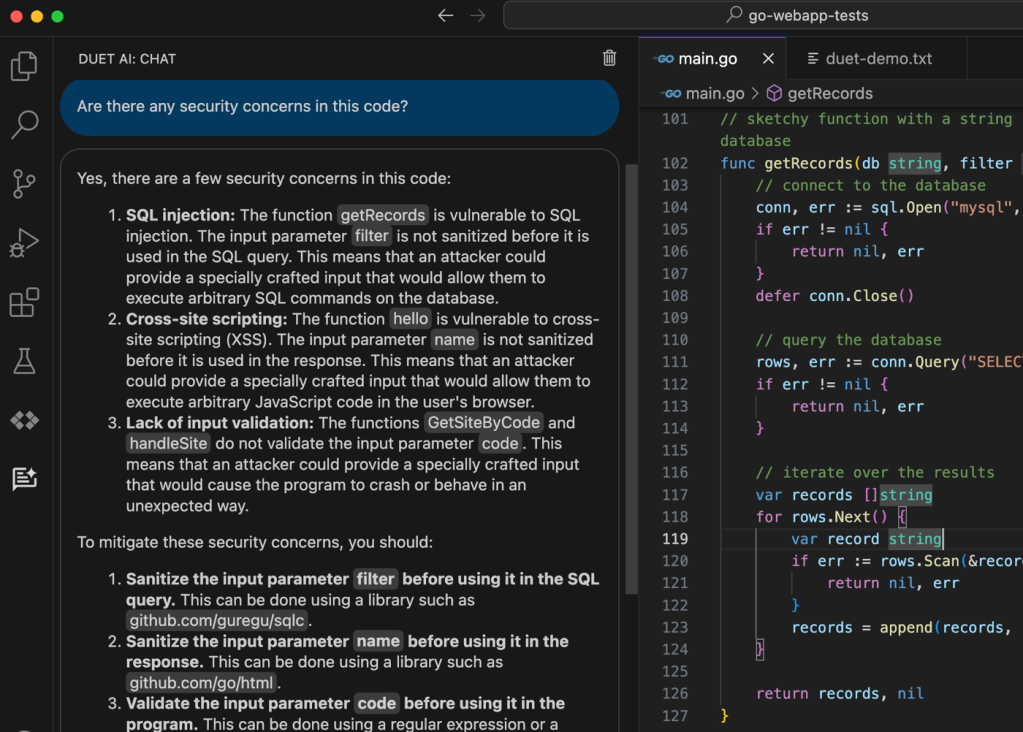

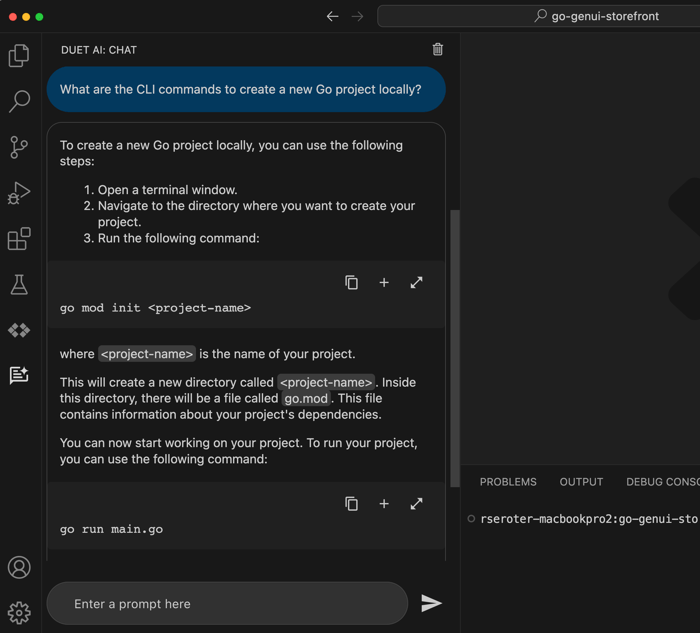

What coding tools can I use with Gemini? GitHub Copilot now supports Gemini models. Folks who love Cursor can choose Gemini as their underlying model. Same goes for fans of Sourcegraph Cody. Gemini Code Assist from Google Cloud puts AI-assisted tools into Visual Studio Code and the JetBrains IDEs. Get the power of Gemini’s long context, personalization on your own codebase, and now the use of tools to pull data from Atlassian, GitHub, and more. Use Gemini Code Assist within your local IDE, or in hosted environments like Cloud Workstations or Cloud Shell Editor.

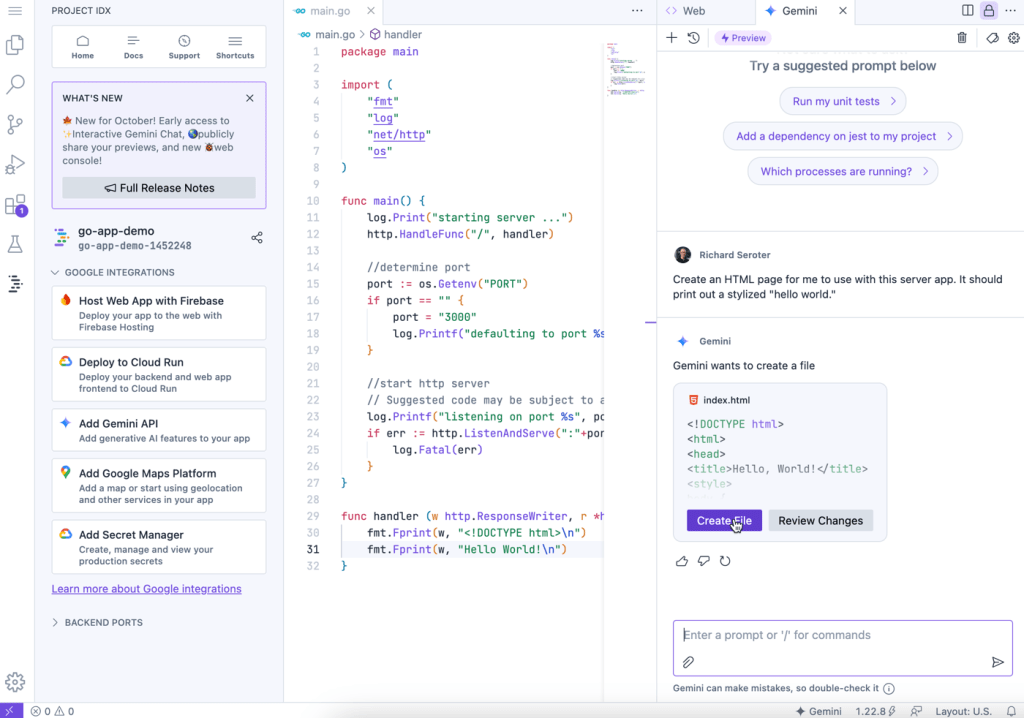

Project IDX is another Google-provided dev experience for building with Gemini. Use it for free, and build AI apps, with AI tools. It’s pretty great for frontend or backend apps.

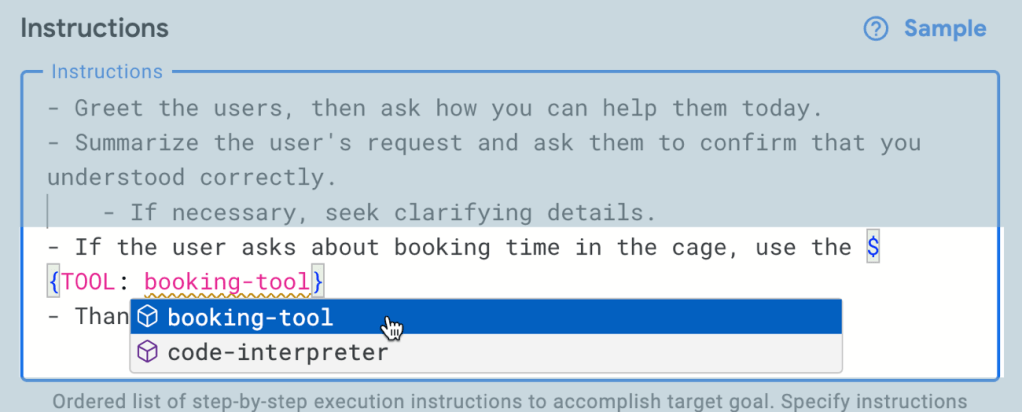

Maybe you’re building apps and agents with Gemini through low-code or declarative tools? There’s the Vertex AI Agent Builder. This Google Cloud services makes it fairly simple to create search agents, conversational agents, recommendation agents, and more. No coding needed!

Another options for building with Gemini is the declarative Cloud Workflows service. I built a workflow that calls Gemini through Vertex AI and summarizes any provided document.

# Summarize a doc with Gemini

main:

params: [args]

steps:

- init:

assign:

- doc_url: ${args.doc_url}

- project_id: ${args.project_id}

- location: ${args.location}

- model: ${args.model_name}

- desired_tone: ${args.desired_tone}

- instructions:

- set_instructions:

switch:

- condition: ${desired_tone == ""}

assign:

- instructions: "Deliver a professional summary with simple language."

next: call_gemini

- condition: ${desired_tone == "terse"}

assign:

- instructions: "Deliver a short professional summary with the fewest words necessary."

next: call_gemini

- condition: ${desired_tone == "excited"}

assign:

- instructions: "Deliver a complete, enthusiastic summary of the document."

next: call_gemini

- call_gemini:

call: googleapis.aiplatform.v1.projects.locations.endpoints.generateContent

args:

model: ${"projects/" + project_id + "/locations/" + location + "/publishers/google/models/" + model}

region: ${location}

body:

contents:

role: user

parts:

- text: "summarize this document"

- fileData:

fileUri: ${doc_url}

mimeType: "application/pdf"

systemInstruction:

role: user

parts:

- text: ${instructions}

generation_config: # optional

temperature: 0.2

maxOutputTokens: 2000

topK: 10

topP: 0.9

result: gemini_response

- returnStep:

return: ${gemini_response.candidates[0].content.parts[0].text}

Similarly, its sophisticated big-brother, Application Integration, can also interact with Gemini through drag-and-drop integration workflows. These sorts of workflow tools help you bake Gemini predictions into all sorts of existing processes.

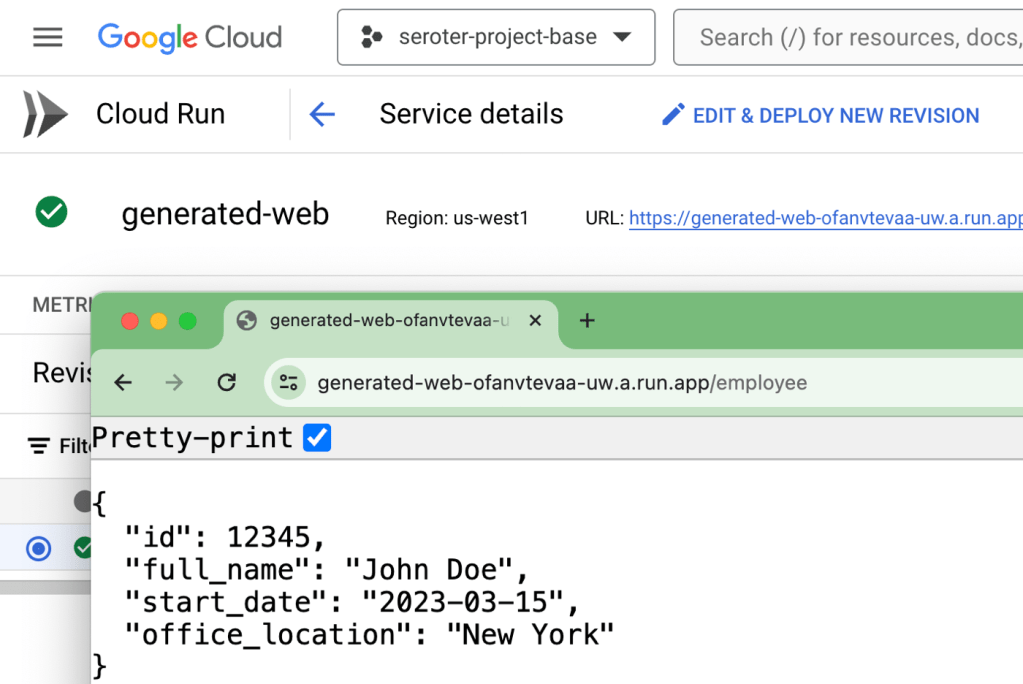

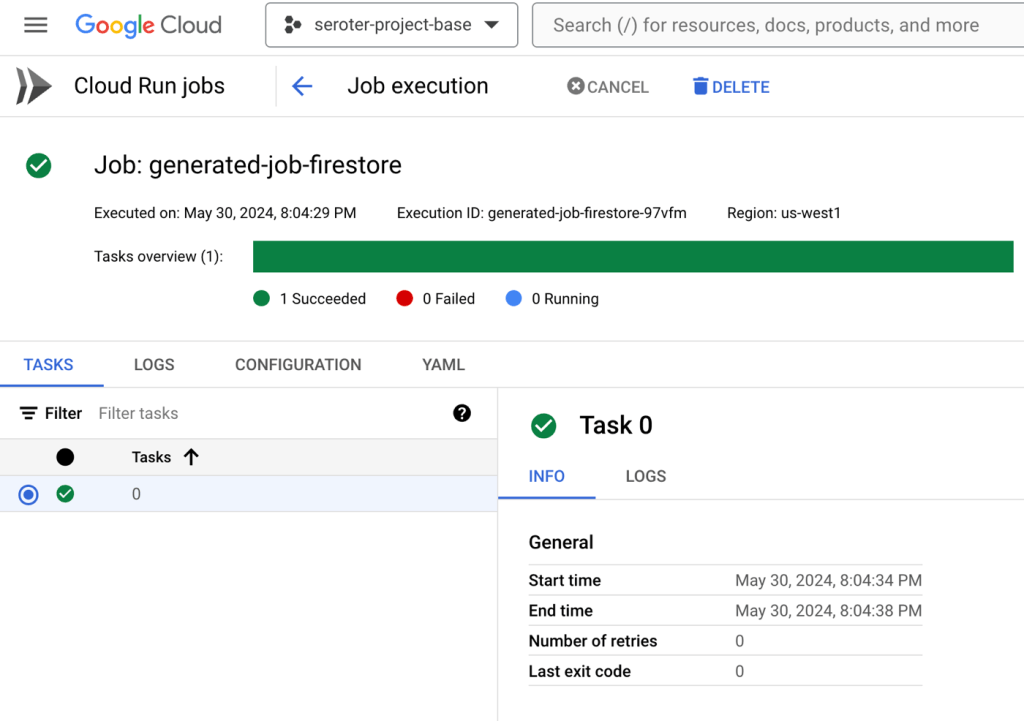

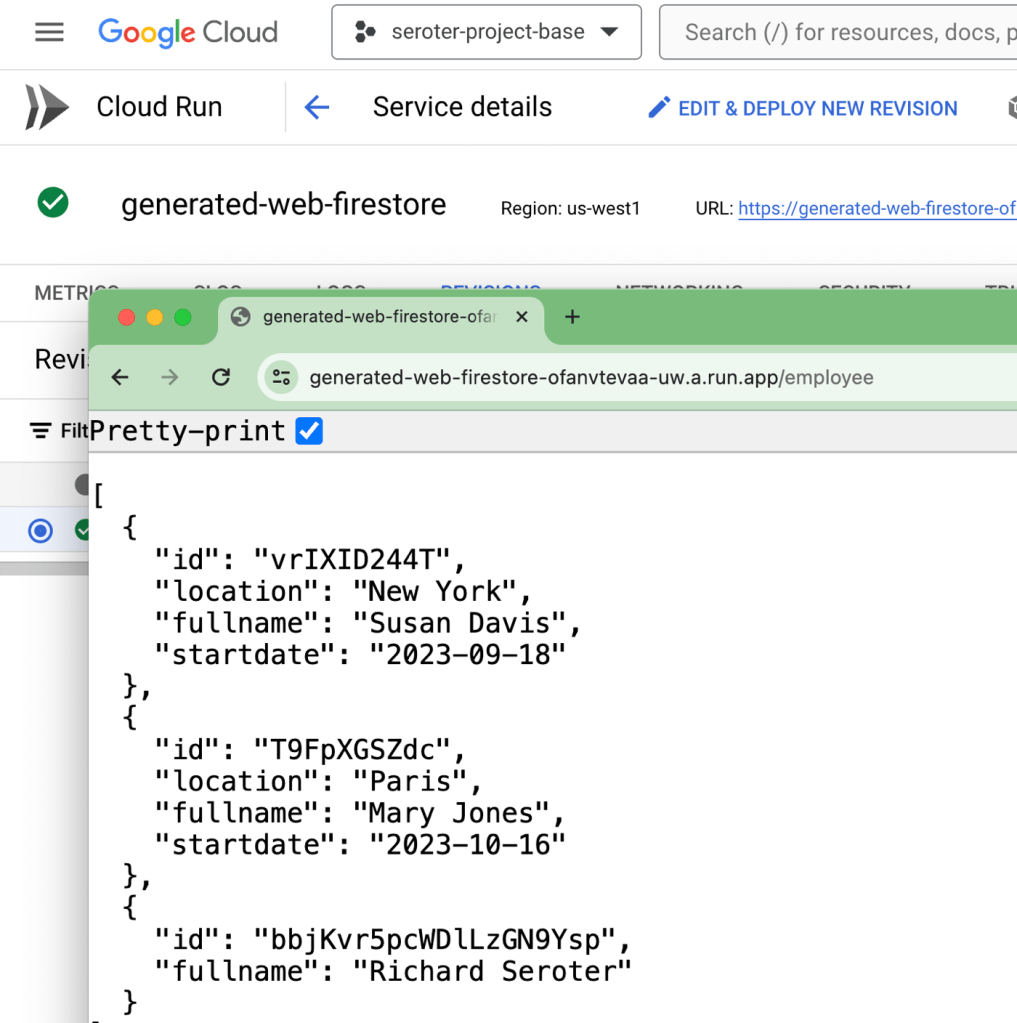

After you build apps and agents, you need a place to host them! In Google Cloud, you’ve could run in a virtual machine (GCE), Kubernetes cluster (GKE), or serverless runtime (Cloud Run). There’s also the powerful Firebase App Hosting for these AI apps.

There are also two other services to consider. For RAG apps, we now offer the Vertex AI RAG Engine. I like this because you get a fully managed experience for ingesting docs, storing in a vector database, and performing retrieval. Doing LangChain? LangChain on Vertex AI offers a handy managed environment for running agents and calling tools.

Build AI and data systems with Gemini

In addition to building straight-up agents or apps, you might build backend data or AI systems with Gemini.

If you’re doing streaming analytics or real-time ETL with Dataflow, you can build ML pipelines, generate embeddings, and even invoke Gemini endpoints for inference. Maybe you’re doing data analytics with frameworks like Apache Spark, Hadoop, or Apache Flink. Dataproc is a great service that you can use within Vertex AI, or to run all sorts of data workflows. I’m fairly sure you know what Colab is, as millions of folks per month use it for building notebooks. Colab and Colab Enterprise offer two great ways to build data solutions with Gemini.

Let’s talk about building with Gemini inside your database. From Google Cloud SQL, Cloud Spanner, and AlloyDB, you can create “remote models” that let you interact with Gemini from within your SQL queries. Very cool and useful. BigQuery also makes it possible to work directly with Gemini from my SQL query. Let me show you.

I made a dataset from the public “release notes” dataset from Google Cloud. Then I made a reference to the Gemini 2.0 Flash model, and then asked Gemini for a summary of all a product’s release notes from the past month.

-- create the remote model

CREATE OR REPLACE MODEL

`[project].public_dataset.gemini_2_flash`

REMOTE WITH CONNECTION `projects/[project]/locations/us/connections/gemini-connection`

OPTIONS (ENDPOINT = 'gemini-2.0-flash-exp');

-- query an aggregation of responses to get a monthly product summary

SELECT *

FROM

ML.GENERATE_TEXT(

MODEL `[project].public_dataset.gemini_2_flash`,

(

SELECT CONCAT('Summarize this month of product announcements by rolling up the key info', monthly_summary) AS prompt

FROM (

SELECT STRING_AGG(description, '; ') AS monthly_summary

FROM `bigquery-public-data`.`google_cloud_release_notes`.`release_notes`

WHERE product_name = 'AlloyDB' AND DATE(published_at) BETWEEN '2024-12-01' AND '2024-12-31'

)

),

STRUCT(

.05 AS TEMPERATURE,

TRUE AS flatten_json_output)

)

How wild is that? Love it.

You can also build with Gemini in Looker. Build reports, visualizations, and use natural language to explore data. See here for more.

And of course, Vertex AI helps you build with Gemini. Build prompts, fine-tune models, manage experiments, make batch predictions, and lots more. If you’re working with AI models like Gemini, you should give Vertex AI a look.

Build a better day-2 experience with Gemini

It’s not just about building software with Gemini. The AI-driven product workflow extends to post-release activities.

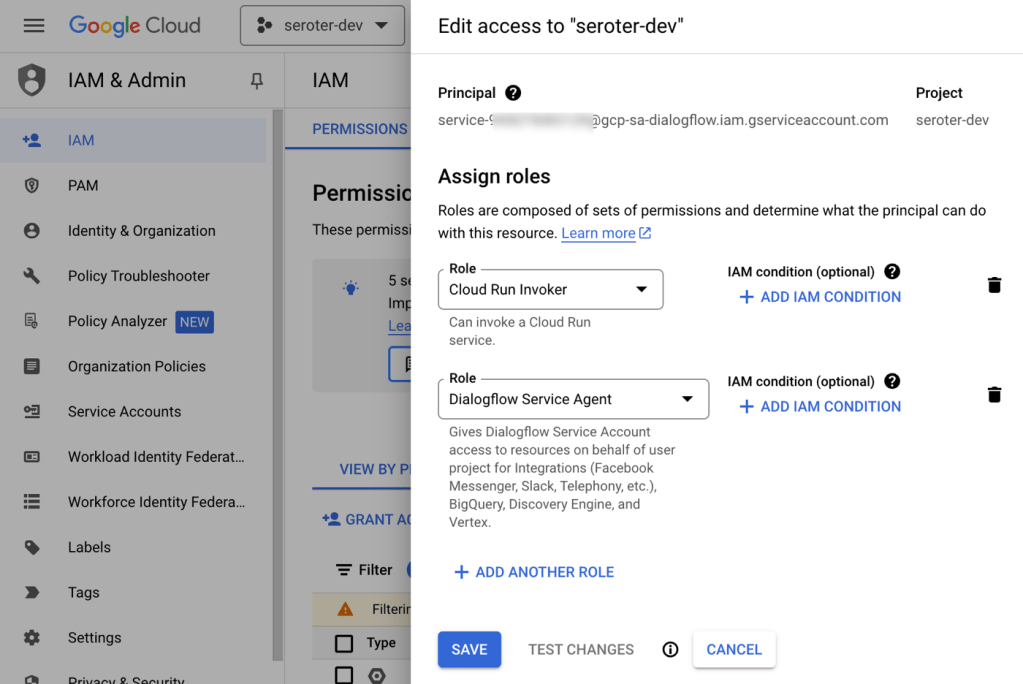

Have to set up least-privilege permissions for service accounts? Build the right permission profile with Gemini.

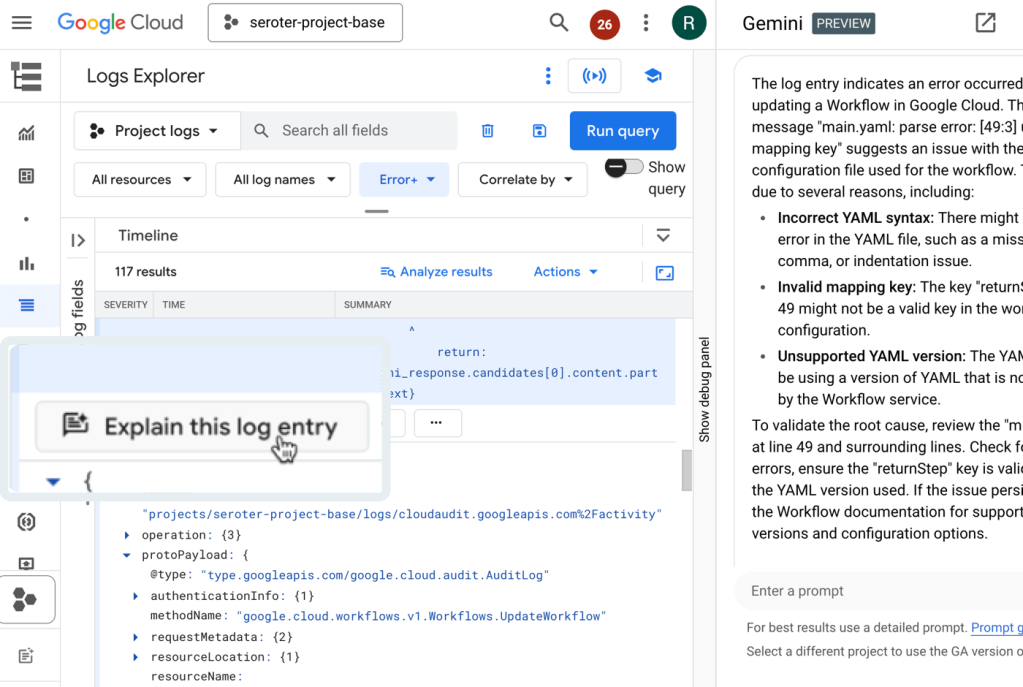

Something goes wrong. You need to get back to good. You can build faster resolution plans with Gemini. Google Cloud Logging supports log summarization with Gemini.

Ideally, you know when something goes wrong before your customers notice. Synthetic monitors are one way to solve that. We made it easy to build synthetic monitors with Gemini using natural language.

You don’t want to face security issues on day-2, but it happens. Gemini is part of Security Command Center where you can build search queries and summarize cases.

Gemini can also help you build billing reports. I like this experience where I can use natural language to get answers about my spend in Cloud Billing.

Build supporting digital assets with Gemini

The developer workflow isn’t just about code artifacts. Sometimes you create supporting assets for design docs, production runbooks, team presentations, and more.

Use the Gemini app (or our other AI surfaces) to generate images. I do this all the time now!

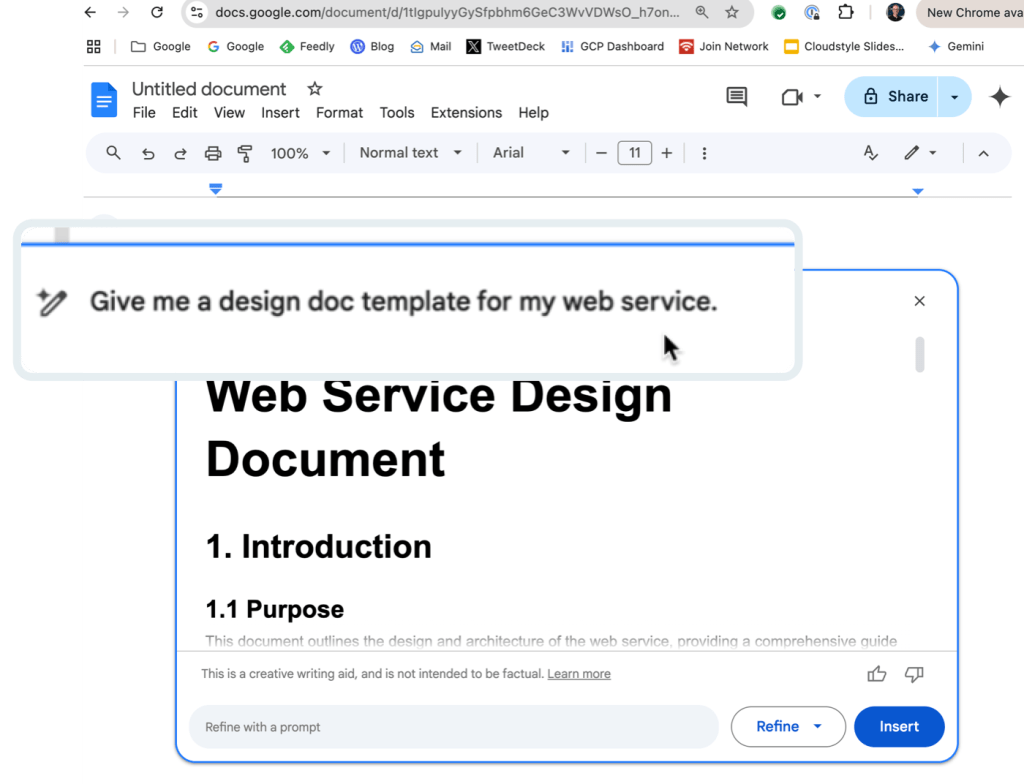

Building slides? Writing docs? Creating spreadsheets? Gemini for Workspace gives you some help here. I use this on occasion to refine text, generate slides or images, and update tables.

Maybe you’re getting bored with static image representations and want some more videos in your life? Veo 2 is frankly remarkable and might be a new tool for your presentation toolbox. Consider a case where you’re building a mobile app that helps people share cars. Maybe produce a quick video to embed in the design pitch.

AI disrupts the traditional product development workflow. Good! Gemini is part of each stage of the new workflow, and it’s only going to get better. Consider introducing one or many of these experiences to your own way of working in 2025.